PUBLIC-SECTOR MANAGERIAL VALUES: UNITED STATES,

advertisement

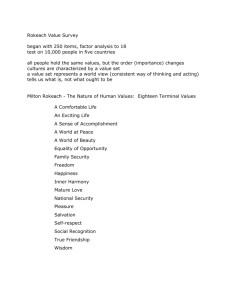

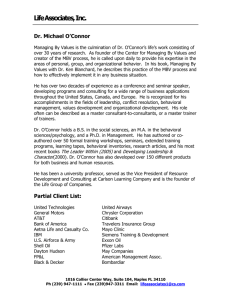

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ORGANIZATION THEORY AND BEHAVIOR, 9 (2), 147-173 SUMMER 2006 PUBLIC-SECTOR MANAGERIAL VALUES: UNITED STATES, CANADA, AND JAPAN Patrick E. Connor, Boris W. Becker, Larry F. Moore, and Yoshiju Okubo* ABSTRACT. This paper reports an investigation of the personal-values systems of 567 public-sector managers from the U.S., Canada, and Japan. The results of this research indicate that, despite some specific differences, there is an overarching, coherent North American public-sector managerial values systems. Moreover, it is similar in some ways to that of its Japanese counterparts. However, these values systems – North American and Japanese – are clearly distinct. INTRODUCTION “The study of values has special importance to the field of public administration today because of the unusual level of change under way in the political-administrative system. The system is currently experiencing policy shifts ..., as well as organizational adjustments stemming from those systemic shifts” (Wart, 1998, p. 164). If Van --------------------------------* Patrick E. Connor, Ph.D., is Professor, Atkinson Graduate School of Management, Willamette University. His research interests center on two themes, managers' personal value systems and organizational change. Boris W. Becker, Ph.D., is Emeritus Professor, College of Business, Oregon State University. His research interests focus on values as theoretical construct and empirical variable in managerial and consumer behavior. Larry F. Moore, Ph.D., is Emeritus Professor, Sauder School of Business, University of British Columbia. His research interests are in work motivation and workforce diversity in organizations. Yoshiju Okubo, B.Eng., is Associate Professor, Graduate School of Management and Economics, Aomori Public College, Aomori, Japan. His research interests are in high-tech human resource development and software engineering. Copyright © 2006 by PrAcademics Press 148 CONNOR, BECKER, MOORE & OKUBO Wart is right, the values of those working in the public sector bear examining. And if he is right about policies changing, then the values of public-sector managers seem especially worthy of study. Since it is fair to say that every country has a "public sector," our inquiry was guided by the question, "Are the personal-values systems of publicsector managers similar or different when compared across countries?" The purpose of this article is to report our findings relative to this question, with specific reference to the U.S., Canada, and Japan. Interest in questions such as this – that is, interest in human values systems – dates back many years (Allport, 1937; England, 1967; Guth & Tagiuri, 1965; Kluckhohn & Strodtbeck, 1961; Lewin, 1935; Postman, Bruner & McGinnes, 1948). That interest increased with the publication of Milton Rokeach's landmark Beliefs, Attitudes and Values (1968), leading to a substantial growth in the conceptual and empirical literature on personal values. Contributions in the past two-plus decades have ranged from attempts to integrate the values concept into middle-range theories (e.g., Gutman, 1982), to massive empirical studies (Hofstede, 2001; House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman, & Gupta, 2004; Kahle, 1984; Posner & Schmidt, 1984, 1992; PrinceGibson & Schwartz, 1998; Schwartz, 1992). Reviews can be found in Agle & Caldwell (1999), Burgess (1992), Connor and Becker (1994), England and Lee (1974), House et al. (2004), Rokeach (1979), Stackman, Pinder & Connor (2000). With all the work being done, a reasonably consensual definition of "values" has emerged over the past several decades. Kluckhohn (1951, p. 398), from an anthropological perspective, defined values as "a conception, explicit or implicit . . . of the desirable which influences the selection from available modes, means, and ends of action." England (1967, p. 54) viewed values as composing "a relatively permanent perceptual framework which shapes and influences the general nature of an individual's behavior." For Williams (1968; 1979, p. 16), the core phenomenon is that values serve as "criteria or standards of preference." And, in his elaboration of Kluckhohn's concepts, psychologist Rokeach (1968, p. 124) defined values as "abstract ideals, not tied to any specific object or situation, representing a person's belief about modes of conduct and ideal terminal modes . . .." Values therefore are global beliefs that "transcendentally guide actions and judgments across specific PUBLIC-SECTOR MANAGERIAL VALUES: AND JAPAN UNITED STATES, CANADA, 149 objects and situations" (Rokeach, 1968, p. 160). Schwartz and Bilsky (1987, p. 551) summarize the literature by specifying that "… values are (a) concepts or beliefs, (b) about desirable end states or behaviors, (c) that transcend specific situations, (d) guide selection or evaluation of behavior and events, and (e) are ordered by relative importance." As a point of clarification, we note that values are distinct from attitudes, which do focus on specific objects and situations: "An attitude is an orientation towards certain objects (including persons – others and oneself) or situations . . . . [A]n attitude results from the application of a general value to concrete objects or situations" (Theodorson & Theodorson, 1969, p. 19). Values therefore may be conceptualized as global beliefs about desirable end-states or modes of behavior that underlie attitudinal processes and behavior. Behavior is the manifestation of one's fundamental values and corresponding attitudes (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Fazio, 1986); as Adler (2002, p. 17) notes, "individuals express their culture and its normative qualities through the values that they hold about life and the world around them." RESEARCH QUESTION AND BACKGROUND It is beyond the scope of this paper to examine the social, economic, technological, and other contextual variables that affect acculturation processes. We can say, however, that two broad lines of reasoning have been advanced, historically, in such comparative research as we report here (Tan, 2002). A number of scholars have investigated personal values systems of people around the world, finding them to support a divergence line of reasoning – that is, to find that they differ substantially across countries [see, for example, Connor, Becker, Kakuyama & Moore (1993), Dubinsky, Kotabe, Lim and Wagner (1997), England (1975), Glazer and Beehr, (2002), House et al. (2004), Sagiv and Schwartz (2000), Schwartz (1992), Schwartz and Bardi (2001)]. With specific reference to managers, Americans are said to prize achievement, whereas Japanese prefer ascribed status more (House et al. 2004), as well as hierarchy and harmony (Sagiv & Schwartz, 2000) and respect (Connor et al., 1993). For their part, Canadian managers have been described as regarding harmony and egalitarianism more highly than their American 150 CONNOR, BECKER, MOORE & OKUBO counterparts do (Sagiv & Schwartz, 2000). These various differences are held to reflect fundamental differences in cultural values as between Canada and the U.S. (Hardin, 1974; House et al. 2004; Lipset, 1990). Accordingly, based on this perspective, it follows that the values of American, Japanese, and Canadian public-sector managers should be significantly different from each other. On the other hand, a good case may be made for there being a significant relationship between individuals' personal values and their occupation [see, for example, Becker and Connor (1996), Glazer and Beehr (2002), Rokeach, Miller and Snyder (1971)]. Schneider (1987) and Schneider, Goldstein, and Smith (1995) have postulated an "Attraction-Selection-Attrition" dynamic, by which people are attracted to, selected by, and remain with an occupation in which their personality, attitudes, and values match those of their occupation (Glazer and Beehr, 2002, p. 187). This is a convergence line of reasoning (Tan, 2002), and may well apply to those who participate in the "public administration" occupation, with its putative universal emphasis on responsiveness, performance, accountability and responsibility, social equity, due process, openness, financial conservatism, standards of fairness to employees, and notions of contribution to the common good (Behn, 1999; Van Wart, 1998). Based on this perspective, it follows that the values of American, Japanese, and Canadian public-sector managers should be substantially the same. Research Question The research literature does not provide a resolution of these two competing lines of reasoning. In examining the "public-is-different" viewpoint, Perry and Rainey (1988) ask whether it is rooted in myth, or whether in fact there are unique qualities that characterize the public sector. They conclude that a clear empirical answer is elusive, owing to a diversity of study designs, samples, and focal variables. The same sorts of concerns pertain to values research, as Connor and Becker (1994) found in attempting to answer their question, "what do we know about personal values systems, and why don't we know more?" Consequently, the present investigation was designed to determine if the values systems of public-sector managers are country-specific or universal – whether they diverge or converge. PUBLIC-SECTOR MANAGERIAL VALUES: AND JAPAN UNITED STATES, CANADA, 151 Specifically, the question here is whether public-sector managers from the U.S., Canada, and Japan hold significantly different, or essentially similar, personal values.1 Background Of the limited research that has been conducted on public-sector managers' personal-values systems, U.S. managers have received the lion's share. Sikula (1973), for example, reported U.S. federal executives as holding most highly values such as family security, selfrespect, accomplishment, and being responsible and capable. Schmidt and Posner (1987) investigated the values preferences of California city managers and U.S. federal executives. Both groups especially valued honesty, responsibility, and capability. More recently, Boyne (2002) has found American public-sector employees to be rather non-materialistic in their values preferences. In her review of the values of American public-sector managers, deLeon (1994) noted that city managers, city planners, federal government executives, and public-management graduate students have given consistently high rankings to values such as self-respect, family security, accomplishment, and honesty, responsibility, and capability. In a rare study of the values of Canadian public-sector managers, Becker and Connor (2005) found that they ranked highly the values of being helpful and loving, together with having inner harmony and wisdom. As under-examined as Canadian public-sector managerial values are, we found no literature at all describing the personal-values systems of Japanese public-sector managers. METHOD Samples The American sample of 161 respondents are State-government managers, from a western state, who attended a management development workshop as a part of the annual meeting of their State Management Association. Males constituted 61.5 percent of the 152 CONNOR, BECKER, MOORE & OKUBO sample, females 38.5 percent, with an average age of 43.3 years (s.d. 9.68, range 20-63). The Canadian sample consists of 232 managers who were participants in a number of university-sponsored management workshops and executive-development programs in western Canada. 55.6 percent were males and 44.4 percent were females, with an average age of 40.8 years (s.d. 7.76, range 24-61). All serve at the Provincial level of government. Finally, the Japanese sample comprises 174 managers, all of whom serve at the Prefectural level of government in the north of Honshu Island. Of the 171 who reported their gender, all but ten were males (94.2 percent and 5.8 percent, males and females respectively), with an average age of 46.5 years (s.d. 6.40, range 3360). A word here about male and female percentages: We were startled at the small number of females in our Japanese sample, and were concerned that we had erred in drawing it. After some investigation however, we realized that 5.8 percent is actually representative of female managers in the Japanese public sector: Across the 47 Japanese prefectures, the proportion of prefecturalgovernment female managers ranges from 3.9 to 6.7 percent, with an average of 5.4 percent (Japan Statistics, 2003). The three samples' respondents neatly fit Perry and Rainey's (1988) typology of organizations, which is based on ownership, funding, and mode of social control. Our managers function at comparable levels of government (State, Province, Prefecture), and can be described as participating in "Bureau" organizations, characterized by public ownership, public funding, and polyarchical social control, "involving a pluralistic political process in which multiple governmental authorities, interest groups, and other political actors contest the nature and application of [rules and directives]" (Perry & Rainey, 1988, p. 193). Instrument Values were measured by means of the Rokeach Value Survey (RVS), Form D (Rokeach, 1973). The RVS is one of the most popular structured instruments for measuring values systems, reflecting the Rokeachian concept of values described above. PUBLIC-SECTOR MANAGERIAL VALUES: AND JAPAN UNITED STATES, CANADA, 153 The RVS is composed of two sets of values, Terminal and Instrumental, as shown in Table 1. "Terminal" values describe desirable conditions, or that which one might wish to have, such as TABLE 1 Terminal and Instrumental Values Terminal A Comfortable Life (a prosperous life) An Exciting Life (a stimulating, active life) A Sense of Accomplishment (lasting contribution) A World at Peace (free of war and conflict) A World of Beauty (beauty of nature and the arts) Equality (brotherhood, equal opportunity for all) Family Security (taking care of loved ones) Freedom (independence) Happiness (contentedness) Instrumental Ambitious (hard-working, aspiring) Broadminded (open-minded) Capable (competent, effective) Cheerful (lighthearted, joyful) Clean (neat, tidy) Courageous (standing up for your beliefs Forgiving (willing to pardon others) Helpful (working for the welfare of others) Honest (sincere, truthful) Inner Harmony (freedom from inner conflict) Mature Love (sexual and spiritual intimacy) National Security (protection from attack) Pleasure (an enjoyable life) Imaginative (daring, creative) Salvation (saved, eternal life) Loving (affectionate, tender) Self-Respect (self-esteem) Social Recognition (respect, admiration) True Friendship (close companionship) Wisdom (a mature understanding of life) Obedient (dutiful, respectful) Polite (courteous, well-mannered) Source: Rokeach (1973, p. 28) Independent (self-reliant, selfsufficient) Intellectual (intelligent, reflective) Logical (consistent, rational) Responsible (dependable, reliable) Self-controlled (restrained, welldisciplined) 154 CONNOR, BECKER, MOORE & OKUBO family security, equality, or salvation. "Instrumental" values describe desirable modes of conduct, or that which one might wish to be, such as independent, loving, or honest. Each set consists of a list of 18 distinct values; within each set, the individual arranges the 18 values in order of his or her preference. Respondents, therefore, report two sets of 18 ranked values. Standard procedures were employed in the administration of the instrument. Form D of the RVS uses gummed labels, by which the respondent physically arranges his or her values in the preferred priority ranking. Japanese translations were those used in Calista's research, in which the "double-back technique" was employed (1984, p. 552): The instrument's translation began with two Japanese professors, who were on research leaves in the United States, successively translating from English to Japanese and then each version back into English. A third English-language professor in Japan negotiated the few remaining differences in Japanese; it was then translated back into English by two Japanese professors who are holders of American doctorates in linguistics; the result was a one-to-one agreement with the original English.2 The same translations were used in the research reported by Connor, et al. (1993), and as an additional check the English-fluent Japanese coauthor of that article translated the instrument into English, again with one-to-one agreement with the original. Analysis Since the RVS produces ranked – and therefore ordinal – data, differences between groups of individuals are measured using medians, rather than means. Consequently, the nonparametric chisquare statistic is used to test whether a value is evaluated at a difference that is statistically significant as between the groups being compared (Siegel & Castellan, 1988).3 Extensive evidence on the validity, reliability, and factorial structure of the RVS is available in Rokeach (1973). As Rokeach and Ball-Rokeach (1989, p. 776) have PUBLIC-SECTOR MANAGERIAL VALUES: AND JAPAN UNITED STATES, CANADA, 155 noted, "Test-retest reliability has been assessed separately for each of the 36 values and also for the two sets of values systems (Terminal and Instrumental) . . . . Employing a 14- to 16-month time interval, the median reliability of the values system considered as a whole is 0.69 for Terminal values systems and 0.61 for Instrumental value systems." Because of its relevance to this paper's analysis, the factorial structure of the RVS merits some further discussion. Although intercorrelations among the 36 values have been shown by Rokeach and others to be minimal (Rokeach, 1973), his factor analysis of a national sample of adult Americans (n = 1,409) indicates that the values are not altogether independent of one another: "For the total sample . . . we have been able to identify seven bipolar factors by varimax rotation . . ." (Rokeach, 1973, emphasis added). Table 2 presents those factors, together with the loadings of their contributing values.4 The factorial structure displayed in Table 2 is both relatively robust (Crosby, Bitner & Gill 1990; Frederick & Weber 1987; McCarrey et al., 1984) and analytically valuable (Rokeach 1973). In addition to the individual values themselves, the factors are useful for examining differences in value systems among respondent groups. The way in which this is done can best be explained by an example. Consider the first factor depicted in Table 2; as Rokeach found, it is a bipolar dimension, with Immediate Gratification at one end and Delayed Gratification at the other. If a particular respondent not only ranks highly all those values that load positively, but also ranks highly all those that load negatively, that person may be thought of as being relatively neutral with respect to that particular factor. He or she prefers neither pole to the other. Similarly, if another respondent ranks none of those eight values either high or low, we can say that individual also is expressing no strong orientation with respect to the factor. On the other hand, a third respondent who ranks all four positive-loading values high, and all four negative-loading values low, obviously values Immediate, rather than Delayed, Gratification. 156 CONNOR, BECKER, MOORE & OKUBO To measure the degree to which an individual values one pole or another for a particular factor, two additional elements must be taken into account. First is the relative loading weights of the individual values shown in Table 2. An extreme ranking (high or low) of a TABLE 2 Factor Analytic Structure of Personal Values Factorial Dimension Highest Positive Loadings Highest Negative Loadings Immediate vs. Delayed Gratification A comfortable life (.69) Pleasure (.62) Clean (.47) An exciting life (.41) Logical (.53) Imaginative (.45) Intellectual (.44) Independent (.43) Obedient (.52) Polite (.50) Self-controlled (.37) Honest (.34) A world at peace (.61) National security (.58) Equality (.43) Freedom (.40) A world of beauty (.58) Equality (.39) Helpful (.36) Imaginative (.30) Social recognition (.49) Self-respect (.32) Courageous (.70) Independent (.33) Wisdom (-.56) Inner harmony (-.41) Logical (-.34) Self-controlled (-.33) Forgiving (-.64) Salvation (-.56) Helpful (-.39) Clean (-.34) Broadminded (-.56) Capable (-.51) Competence vs. Conscience Self-Constriction vs. Self-Expansion Social vs. Personal Orientation Societal vs. Family Security Respect vs. Love Inner- vs. OtherDirected True friendship (-.49) Self-respect (-.48) Family security (-.50) Ambitious (-.43) Responsible (-.33) Capable (-.32) Mature love (-.68) Loving (-.60) Polite (-.34) Source: Rokeach (1973). heavily-weighted value suggests more strongly that a respondent values the pole than would a similar ranking of a lightly-loading value. Second is the total number of value weights available for the factor. For instance, it is obvious from Table 2 that respondents PUBLIC-SECTOR MANAGERIAL VALUES: AND JAPAN UNITED STATES, CANADA, 157 stand a greater chance of ranking (either high or low) a value that contributes to the Immediate/Delayed Gratification factor than one that contributes to the Inner-/Other-Directed factor: Eight values, ∑ |total loadings| = 3.83, are available for the former, whereas only three, ∑ |total loadings| = 1.37, are available for the latter. Thus, the relative high or low ranking of its contributing values, weighted by the individual value loadings, and standardized by the total weightings available, provides a sense of the "distance" an individual's value orientation is away from neutral toward either pole of a given factor dimension. The procedure for calculating these "distances" for individuals and for groups is detailed in Connor et al. (1993), and Connor and Becker (2003). RESULTS Comparisons of the personal values systems of the managers investigated in the present study are developed in the accompanying tables and figure. U.S. – Canadian As Table 3 shows, there are a number of dissimilarities in the values of our U.S. and Canadian public-sector managers. Of 36 possibilities, eleven are significantly as different as between our two samples.5 Despite these differences, Table 3 also shows – and this is consistent with the findings of Adler and Graham (1987) and Connor, et al. (1993) – that there are many (25) similarities in the values of our U.S. and Canadian respondents as well. Most tellingly, the strong Spearman's Rank correlations for both Terminal and Instrumental values (0.93 and 0.94, respectively) suggest that these two samples come from highly similar populations. TABLE 3 Personal Values of U.S., Canadian, and Japanese Public-Sector Managers Value A Comfortable Life US Median (Rank) 11.29 Canada Japan Chi-Square Median Median USUS-Japan Canada(Rank) (Rank) Canada Japan 10.42 7.26 0.42 20.88a 8.97a 158 An Exciting Life Accomplishment A World at Peace CONNOR, BECKER, MOORE & OKUBO (11) 11.73 (12) 6.91 (6) 11.04 (10) (11) 10.06 (10) 7.31 (7) 12.86 (15) (5) 8.25 (8) 14.07 (17) 7.64 (6) 4.00b 18.03a 6.29b 0.19 99.9 a 80.72a 4.47 b 9.22 a 19.36a PUBLIC-SECTOR MANAGERIAL VALUES: AND JAPAN UNITED STATES, CANADA, 159 TABLE 3 (Continued) Value A World of Beauty Equality Family Security Freedom Happiness Inner Harmony Mature Love National Security Pleasure Salvation Self-respect Social Recognition True Friendship Wisdom Ambitious Broadminded Capable Cheerful Clean Courageous Forgiving US Median (Rank) 13.53 (15) 12.54 (13) 5.21 (2) 6.44 (5) 7.41 (7) 6.38 (4) 8.45 (8) 15.04 (18) 13.61 (16) 14.79 (17) 4.11 (1) 13.38 (14) 9.32 (9) 5.66 (3) 9.65 (10) 8.44 (6) 6.13 (3) 11.38 (15) 14.94 (17) 9.22 (9) 10.13 (12) Canada Japan Chi-Square Median Median USUS-Japan Canada(Rank) (Rank) Canada Japan 13.40 (16) 12.45 (13) 3.27 (1) 7.17 (6) 6.59 (3) 6.62 (4) 7.63 (9) 16.50 (17) 12.75 (14) 17.44 (18) 5.17 (2) 12.21 (12) 7.50 (8) 7.00 (5) 8.71 (8) 8.42 (6) 6.06 (3) 10.75 (13) 15.30 (17) 8.50 (7) 11.56 (14) 13.00 (14) 8.00 (7) 2.54 (1) 6.33 (4) 5.87 (3) 8.43 (9) 13.50 (16) 12.93 (13) 5.50 (2) 17.68 (18) 9.64 (11) 13.08 (15) 9.70 (12) 8.77 (10) 9.57 (9) 6.83 (3) 10.75 (14) 9.45 (8) 14.10 (16) 7.23 (4) 7.50 (5) 0.02 0.80 0.58 0.00 19.46 a 26.19a 10.37 a 23.66 a 3.47 0.64 0.07 1.48 2.22 7.84 a 2.10 0.06 8.39 a 7.81a 0.85 51.22 a 59.22a 9.07 a 3.61 30.85a 2.14 103.47 a 76.67a 14.92 a 25.18 a 5.10b 5.97 b 75.09 a 69.89a 3.53 0.06 1.70 7.86 a 0.49 13.14a 6.04b 12.07 a 5.45b 0.10 0.00 0.92 0.01 2.88 3.42 0.08 33.87 a 38.84a 0.56 5.50b 2.91 0.51 1.89 3.86b 0.47 3.58 1.63 5.79b 13.57 a 21.45a 160 CONNOR, BECKER, MOORE & OKUBO TABLE 3 (Continued) Value Helpful Honest Imaginative Independent Intellectual Logical Loving Obedient Polite Responsible Self-controlled US Median (Rank) Canada Japan Chi-Square Median Median USUS-Japan Canada(Rank) (Rank) Canada Japan 10.09 (11) 2.81 (1) 11.05 (14) 7.21 (4) 9.00 (8) 8.87 (7) 7.82 (5) 17.53 (18) 13.77 (16) 4.58 (2) 10.33 (13) 9.96 (11) 2.78 (1) 9.79 (10) 6.87 (4) 9.06 (9) 10.12 (12) 7.25 (5) 17.19 (18) 13.00 (16) 4.41 (2) 12.91 (15) 9.97 (11) 5.14 (2) 8.14 (6) 10.10 (13) 9.72 (10) 14.17 (17) 10.07 (12) 15.63 (18) 13.23 (15) 4.03 (1) 9.26 (7) 0.01 0.05 0.00 0.02 12.41 a 11.74a 1.97 11.01 a 5.24b 0.18 9.01 a 13.58a 0.05 0.53 0.22 4.58b 48.38 a 32.37a 0.43 2.85 6.15 b 1.68 20.38 a 15.17a 1.16 0.50 0.05 0.11 0.64 0.20 8.66 a 1.35 25.02a Terminal Values Rank Correlation: U.S.-Canada (0.93, t = 10.28)a, U.S.Japan (0.26, t = 1.09), Canada-Japan (0.35, t = 1.49) Instrumental Values Rank Correlation: U.S.-Canada (0.94, t = 10.64)a, U.S. Japan (0.39, t= 1.69), Canada-Japan (0.50, t = 2.30)b Notes: a p ≤ 0.01; b p ≤ 0.05. Considering factor scores, both differences and similarities again obtain. Canadian managers value Competence and a Personal Orientation more, and Delayed Gratification less, than do their American counterparts (Table 4). That said, however, preferences of the respondents are in the same direction for the two samples and there are no significant differences for the remaining four factors. This pattern is evident in Figure 1, which illustrates graphically the value profiles for all three samples. PUBLIC-SECTOR MANAGERIAL VALUES: AND JAPAN UNITED STATES, CANADA, 161 FIGURE 1 Value Profiles of American, Canadian, and Japanese Public-Sector Figure 1. Value Profiles ofManagers American, Canadian, and Japanese PublicSector Managers Immediate 100 Gratification Competence Delayed Conscience Inner- Self- Social Societal Constriction Orientation Security Respect Family Love Directed 75 50 25 Neutral 0 -25 -50 -75 -100 Gratification U.S. (n=161) Self- Personal Epansion Orientation Canada (n=232) Security OtherDirected Japan (n=174) U.S. – Japanese Table 3 tells an even more striking story regarding the U.S. – Japanese comparison. Our U.S. and Japanese managers express significantly different preferences on a large number of values – more than half of them (21 of 36), in fact. In contrast to the Americans, Japanese managers especially prefer the values of a comfortable life, equality, pleasure, and being cheerful, forgiving, and imaginative. For their part, our U.S. respondents ranked especially higher a sense of accomplishment, mature love, self-respect, wisdom, and being capable, independent, logical, and loving. The rank correlations for both Terminal and Instrumental values (0.26, 0.39) are among the lowest we have ever seen as between groups hypothesized to be similar. Considering factor scores, Table 4 indicates that in contrast to the Americans, who value Delayed Gratification, a Personal Orientation, and Love, the Japanese managers prefer Immediate Gratification, a 162 CONNOR, BECKER, MOORE & OKUBO Social Orientation, and Respect. Both groups value Self-Expansion and Family Security, although the Americans do more so, and both value Competence and being Inner-Directed. As noted, the respective value profiles are portrayed in Figure 1. TABLE 4 Factor Scores of U.S., Canadian, and Japanese Public-Sector Managers Immediate (+) vs. Delayed (-) Gratification Competence (+) vs. Conscience (-) SelfConstriction (+) vs. SelfExpansion (-) Social (+) vs. Personal (-) Orientation Societal (+) vs. Family (-) Security Respect (+) vs. Love (-) Inner- (+) vs. Other- (-) Directed Mean* (SD) Mean* (SD) -31.99 35.10 -20.28 34.16 Z Factor CanadaJapan (SD) Japan (n = 174) US-Japan Mean* Canada (n = 232) US-Canada US (n = 161) 8.63 36.33 -3.29 a -10.41 -8.14 a a 13.11 41.82 21.87 30.56 30.98 -29.98 33.62 -14.79 36.84 -0.18 -25.17 37.48 -34.15 36.27 -34.91 34.77 -36.39 32.32 -23.83 25.08 0.43 -3.32 a -4.41 a -12.31 44.33 -14.73 45.99 -3.45 a 4.24 a 23.68 50.3 23.16 7.12 8.59 34.27 -2.14b 4.85 1.08 3.73a -4.25 a -4.27 a 44.68 2.37 b -6.68 a -9.42 a 4.55 44.97 0.52 54.71 21.53 57.18 0.10 0.37 0.29 PUBLIC-SECTOR MANAGERIAL VALUES: AND JAPAN UNITED STATES, CANADA, 163 Notes: a p ≤ 0.01; b p ≤ 0.05. Canadian – Japanese Comparing Canadian and Japanese managers yields conclusions similar to those immediately above. Table 3 reveals statistically significant differences on more than one-half (23) of the 36 values. In contrast to the Japanese, Canadian managers especially prefer the values of a sense of accomplishment, self-respect, and of being capable, independent, and loving. Japanese managers, however, ranked comparatively higher those of a comfortable life, pleasure, and of being forgiving and self-controlled. Rank correlations for both Terminal and Instrumental values (0.35, 0.50) are nearly as low as for the American-Japanese comparison. Factor-score results as shown in Table 4 are almost identical to the American-Japanese comparison: As with the U.S. respondents, the Canadian managers value Delayed Gratification, a Personal Orientation, and Love. In contrast, the Japanese managers prefer Immediate Gratification, a Social Orientation, and Respect. Both groups value Competence, Self-Expansion, and Family Security, although the Canadians do more so, and both value being InnerDirected. Again, the respective value profiles are portrayed in Figure 1. Summary of Findings Although there are some significant values differences between them, as Tables 3 and 4 and Figure 1 indicate, both sets of North American managers prefer values of Delayed Gratification, Competence, Self-Expansion, a Personal Orientation, Family Security, Love, and being Inner-Directed. So too, do our Japanese managers value competence, self-expansion, family security, and being innerdirected. However, they also prefer Immediate Gratification, a Social Orientation, and Respect; and they differ on more than one-half of the individual values from each of their North American counterparts. In short, many similarities were found in the values of U.S., Canadian, and Japanese managers. Conversely, a remarkable number of important differences also were illuminated, especially between the North American and Japanese. 164 CONNOR, BECKER, MOORE & OKUBO DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS As with many investigations, some precautions need to be considered in interpreting the results of this research and in drawing any generalizations. We begin with those limitations and conclude with some implications. Limitations and Extensions A couple of precautions seem especially worth noting. First, our participants were not randomly drawn from their country's publicsector managerial population. In common with most empirical work on values and organizational phenomena, even large-scale endeavors such as that of Hofstede (2001), we rely on convenience samples. Each sample resulted from a set of opportunities for access that we were able to develop for each country. Second, we described above the care taken to employ a valid and tested translation of the RVS. As Howard, et al. (1983: 896) have pointed out, however, words may translate accurately, while meanings may not: "For example, most Japanese are not familiar with Christian concepts like 'salvation,' and would not interpret 'equality' in light of 'equality between races or sexes.'" Of course, this weakness of ethnocentrism is not peculiar to the RVS; the ability of any Western instrument to capture Eastern values – or vice-versa – is unclear. Some items may be irrelevant for non-Western respondents, while other more relevant ones may be missing (Hofstede & Bond, 1988). Future research can overcome the kinds of shortcomings noted here, but not with ease. While drawing a random sample of all managers in a nation's public sector strikes us as daunting in the extreme, overcoming the problem of inherent meaning in research instruments seems especially critical – and formidable. It is not, however, completely intractable. As exemplified by Hofstede's work, one or two very large organizations could be the basis of values research, if their organizational units are sufficiently well-articulated. More broadly, however, a multiple effort probably is required. In addition to developing instruments that are less ethnocentric, a massive collaborative, "triangulation" strategy could fruitfully be PUBLIC-SECTOR MANAGERIAL VALUES: AND JAPAN UNITED STATES, CANADA, 165 effected. House's GLOBE project (House, et al., 2004) is one recent serious example of this strategy. He and his multi-nation collaborators surveyed some 17,000 managers in 62 countries, and demonstrated that the use of truly cross-nationally relevant instruments is in fact possible. Implications and Future Direction This research reveals two important findings with respect to public-sector managerial values. First, despite some differences between our U.S. and Canadian public-sector managers, their overall similarity cannot be ignored. As noted above, (a) the direction of their value preferences is identical in all factor-dimension cases (see Table 4 and Figure 1), and (b) despite the individual value differences shown in Table 3, the rank correlations for both Terminal and Instrumental values are extremely high (0.93 and 0.94, respectively). Again, we take these correlations as evidence of highly similar – not fundamentally different – populations (see Stackman, Connor, & Becker, in press, regarding a "public-sector ethos" common to the U.S. and Canada). The second important values-systems finding uncovered in our work is that there are as many significant differences as between the values of both American and Canadian versus Japanese public-sector managers. Again, though, we caution against overemphasizing the differences; there still exist some clear similarities. As Figure 1 illustrates, all three sets of managers favored those values oriented toward Competence (versus Conscience), Self-Expansion (versus SelfConstriction), Family (versus Societal) Security, and being Innerversus Other-Directed. To be sure, the relative strengths of their preferences are not identical. For example, Canadians assigned a higher importance to Competence than did the Americans, who assigned it more importance than did the Japanese, but even the Japanese managers came down on the Competence (as opposed to Conscience) end of the spectrum. The same sort of patterns is obtained for the other three dimensions. In short, for our purpose, Figure 1 suggests that their values differences on these dimensions are in degree, not kind. Where the values differences between our North American and Japanese public-sector managers clearly show up are in the other 166 CONNOR, BECKER, MOORE & OKUBO three dimensions. The Japanese value Immediate Gratification, a Social Orientation, and Respect, whereas both the American and Canadian managers are oriented toward Delayed Gratification, a Personal Orientation, and Love. What all this means regarding managing in the public sector is intriguing. In a five-cohort survey of 1,000 alumni of thirteen U.S. graduate public-sector programs, Light (1999) reports that a public service ethic – "making a difference in the world" – does in fact exist. Respondents, moreover, overwhelmingly would choose a career in the public sector if given the chance again. Whether his findings would be replicated in Japan, we can say that in general the manager's role in public organizations is becoming more complex (Van Wart, 1998; Tompkins, 2005). For one thing, as Kelman (2005) points out in his recent examination of the federal procurement system, the successful public-sector manager must navigate waters that roil with conflicting interests from the top, the bottom, the private sector, unaffiliated parties with their own interests, as well as other agencies. Moreover, no longer is he or she necessarily even a government employee, as contractors from private firms and governmental civil servants often perform the same duties, often in the same office, often at the same time. This complexity is increased when one considers public-sector managers, particularly North American and Japanese managers, interacting across national borders. Future research will be useful in revealing whether they are aware of their values similarities and differences, and whether that awareness is reflected in their interactions, for example in trade negotiations. CONCLUSION So, what is the answer to our research question as to countryspecific vs. universal values systems – that is, as to divergence vs. convergence? Putting it another way, is there a "public-sector managerial values system?" Our answer is consistent with a third line of reasoning, crossvergence, in which values systems emerge as unique configurations, or patterns, somewhere between the polar extremes of divergence or convergence (Ralston, Holt, Terpstra & Yu, 1997; Tan, 2002). The pattern that emerges from the present research indicates that (1) yes, despite some specific differences there is an overarching, coherent North American public-sector PUBLIC-SECTOR MANAGERIAL VALUES: AND JAPAN UNITED STATES, CANADA, 167 managerial values system. Moreover, it is similar in some ways to its Japanese counterpart. However, (2) those values systems, North American and Japanese, are also clearly distinct. Figure 1 illustrates these two points clearly. Given the multidimensional nature of values and their correlates, and the significance of values as influences on subsequent attitudes and behavior, it is evident that much research remains to be done. For example, there is a need for values-based research on other than convenience samples. These are often obtained by gaining access to organizations to which the researcher is consulting, or to data collected in the course of a management-development program. It could be argued, not entirely perversely, that the kinds of organizations that allow researchers to investigate their managers' values are not representative of all organizations. There is also a need to investigate whether the crossvergence pattern revealed here for state/provincial/prefectural managers holds for other levels of public management. As noted above, personal values systems of city- and federal-level public managers have been studied (deLeon, 1994; Sikula, 1973; Schmidt & Posner, 1987). However, it remains to conduct such investigations in nations other than the U.S. Future research should not stop at identifying differences between and among groups of people. As we implied at the outset of this paper, there is additional value in studying, and coming to understand, how individuals' values systems affect their attitudes, their actual behavior, including interactions with others, and ultimately their organizations' performance. NOTES 1. Thanks go to Mike Manuel for his software skills and to Katy Durant for her sensible (to her) coding system, as well as myriad other assistance. Thanks also to Steven Nord for all of the excellent support in preparing this manuscript for publication. 2. We are grateful to Professor Donald J. Calista, Marist College, for providing his Japanese RVS instrument to us. 168 CONNOR, BECKER, MOORE & OKUBO 3. We should acknowledge the minor, albeit ongoing, controversy regarding the use of rankings versus ratings in the measurement of values (Agle and Caldwell, 1999: 367-68). Alwin and Krosnick (1985) had clarified the conceptual distinction between rankings and ratings of values, suggesting that each may have its use. While we recognize the greater statistical tools available to analyze rating data (commonly assumed to be interval-scaled), we believe with Rokeach (1973: 33-34, 42-43; 1979: 132) that rankings are more in keeping with the "priority" nature of values: although a number of values may be rated as a "1," or most important, only one value may be ranked #1. 4. We employed Rokeach's factor analysis owing to the superiority of his sample size (1,409 vs. 567) – see Kim and Mueller (1978: 53-59). We were encouraged by the fact that the analysis of McCarrey, et al. (1984) produced identical factors to Rokeach's. Note too that our labeling of the second factor, Competence vs. Conscience, follows that of McCarrey, et al., Connor, et al. (1993), and Connor and Becker (2003); Rokeach (1973) labeled this factor Competence vs. Religious Morality. Finally, note that Rokeach's description of the Inner- vs. Other-Directed dimension in his text (1973, p. 48) differs from his table (p. 47). We believe that the text, and not the table, is correct. 5. Differences between groups that seem trivial (for example, family security and obedient in Table 3) are statistically significant because of the distribution of preferences among the respondents in the samples. REFERENCES Adler, N.J. (2002). International Dimensions of Organizational Behavior (4th ed.). Cincinnati, OH: Southwestern. Adler, N.J., & Graham, J.L. (1987). “Business Negotiations: Canadians Are Not Just Like Americans.” Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 4: 211-238. Agle, B.R., & Caldwell, C.B. (1999). “Understanding Research on Values in Business.” Business and Society, 38 (3): 326-387. PUBLIC-SECTOR MANAGERIAL VALUES: AND JAPAN UNITED STATES, CANADA, 169 Ahmed, S.A. (1990). “Impact of Social Change on Job Values: A Longitudinal Study of Quebec Business Students.” Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 7: 12-24. Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Allport, G.W. (1937). Personality: a Psychological Interpretation. New York: Henry Holt. Alwin, D. F., & Krosnick, J.A. (1985). “The Measurement of Values in Surveys: A Comparison of Ratings and Rankings.” Public Opinion Quarterly, 49: 535-552. Apasu, Y., Ichikawa, S., & Graham, J. (1987). “Corporate Culture and Sales Force Management in Japan and America.” Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 7: 51-62. Becker, B.W., & Connor, P.E. (1996). “Dentists' Personal Values: An Exploratory Investigation.” Journal of the American Dental Association, 127: 503-509. Becker, B.W., & Connor, P.E. (2005). “Self-Selection or Socialization Of Public- and Private-Sector Managers? A Cross-Cultural Values Analysis.” Journal of Business Research, 58 (1): 111-113. Behn, R.D. (1999). “The New Public-Management Paradigm and the Search for Democratic Accountability.” International Public Management Journal, 1 (2): 131-165. Boyne, G.A. (2002). “Public and Private Management: What's the Difference?” Journal of Management Studies, 39 (1): 97-122. Burgess, S.M. (1992). “Personal Values and Consumer Research: An Historical Perspective.” Research in Marketing, 11: 35-79. Calista, D.J. (1984). “Postmaterialism and Value Convergence: Value Priorities of Japanese Compared with their Perceptions of American Values.” Comparative Political Studies, 16: 529-555. Cochrane, R., Billig, M., & Hogg, M. (1979). “British Politics and the Two-Value Model.” In M. Rokeach (Ed.), Understanding Human Values: Individual and Societal (pp. 179-191). New York: The Free Press. 170 CONNOR, BECKER, MOORE & OKUBO Connor, P.E., & Becker, B.W. (1994). “Personal Values and Management: What Do We Know and Why Don't We Know More?” Journal of Management Inquiry, 3 (1): 67-73. Connor, P.E., & Becker, B.W. (2003). “Personal Value Systems and Decision-Making Styles of Public Managers.” Public Personnel Management, 32: 155-180. Connor, P.E., Becker, B.W., Kakuyama, T., & Moore, L.F. (1993). “A Cross-National Comparative Study of Managerial Values: United States, Canada, and Japan.” Advances in International Comparative Management, 8: 3-29. Crosby, L.A., Bitner, M.J., & Gill, J.D. (1990). “Organizational Structure of Values.” Journal of Business Research, 20: 123-134. deLeon, L. (1994). “The Professional Values of Public Managers, Policy Analysts and Politicians.” Public Personnel Management, 23 (1): 135-152. Dubinsky, A.J., Kotabe, M., Lim, C.U., & Wagner, W. (1997). “The Impact of Values on Salespeople’s Job Responses: A CrossNational Investigation.” Journal of Business Research, 39 (3): 195-208. England, G.W. (1967). “Personal Value Systems of American Managers.” Academy of Management Journal, 10 (1): 53-68. England, G.W. (1975). The Manager and his Values. New York: Ballinger. England, G.W., & Lee, R. (1974). “The Relationship between Managerial Values and Managerial Success in the United States, Japan, India and Australia.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 59: 411-419. Fazio, R.H. (1986). “How Do Attitudes Guide Behavior?” In R.M. Sorrentino, and E.T. Higgins, (Eds.), Handbook of Motivation and Cognition: Foundation of Social Behavior (pp. 204-243). New York: Guilford. Feather, N.T. (1979). “Assimilation of Values in Migrant Groups.” In M. Rokeach, (Ed.), Understanding Human Values: Individual and Societal (pp. 97-128). New York: The Free Press. PUBLIC-SECTOR MANAGERIAL VALUES: AND JAPAN UNITED STATES, CANADA, 171 Frederick, W.C., & Weber, J. (1987). “The Values of Corporate Managers and their Critics: An Empirical Description and Normative Implications.” Research in Corporate Social Performance and Policy, 9: 131-152. Glazer, S., & Beehr, T.A. (2002). “Similarities and Differences in Human Values between Nurses in Four Countries.” International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 2: 185-202. Guth, W.D., & Tagiuri, R. (1965). “Personal Values and Corporate Strategies.” Harvard Business Review, 43: 123-132. Gutman, J. (1982). “A Means-End Chain Model Based on Consumer Categorization Processes.” Journal of Marketing, 46: 60-72. Hardin, H. (1974). A Nation Unaware: The Canadian Economic Culture. Vancouver, Canada: J.J. Douglas. Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture's Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations across Nations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Hofstede, G., & Bond, M.H. (1988). “The Confucius Connection: From Cultural Roots to Economic Growth.” Organizational Dynamics, 16: 4-21. House, R.J, Hanges, P.J, Javidan, M., Dorfman, P.W., & Gupta, V. (2004). Culture, Leadership, and Organizations. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage. Howard, A., Shudo, K., & Umeshima, M. (1983). “Motivation and Values among Japanese and American managers.” Personnel Psychology, 36: 883-898. “The Appointment Status of Women to Local Government Management” (2003). In Japan Statistics. [Online] Available at http://www.gender.go.jp/2003statistics/2-2-4.pdf. [Retrieved Feb. 4, 2006]. Kahle, L.R. (1984). Social Values and Adaptation to Life in America. New York: Praeger Publishers. Kamakura, W.A., & Mazzon, J.A. (1991). “Values Segmentation: A Model for the Measurement of Values and Value Systems.” Journal of Consumer Research, 18: 208-218. 172 CONNOR, BECKER, MOORE & OKUBO Kelman, S. (2005). Unleashing Change: A Study of Organizational Renewal in Government. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. Kim, J., & Mueller, C.W. (1978). Factor Analysis: Statistical Methods and Practical Issues. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Kluckhohn, C. (1951). “Values and Value Orientations in the Theory of Action.” In T. Parsons, and E. Shils (Eds.). Toward a General Theory of Action (pp. 388-433). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Kluckhohn, C., & Strodtbeck, F.L. (1961). Variation in Value Orientations. Evanston, IL: Row, Peterson. Lewin, K. (1935). A Dynamic Theory of Personality. New York: McGraw-Hill. Light, P. (1999). The New Public Service. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. Lipset, S.M. (1990). Continental Divide. New York: Routledge, Chatman and Hall. McCarrey, M.W., Gasse, S., & Moore, L. (1984). “Work Value Goals and Instrumentalities: A Comparison of Canadian West-Coast Anglophone and Quebec City Francophone Managers.” International Review of Applied Psychology, 33: 291-303. Perry, J.L., and Rainey, H.G. (1988). “The Public-Private Distinction in Organization Theory: A Critique and Research Strategy.” Academy of Management Review, 13: 182-201. Posner, B.Z. & Schmidt, W.H. (1984). “Values and the American Manager: An Update.” California Management Review, 26: 202-216. Posner, B.Z., & Schmidt, W.H. (1992). “Values and the American Manager: An Update Updated.” California Management Review, 34 (3): 80-94. Postman, J.J., Bruner, S., & McGinnis, E. (1948). “Personal Values as Selective Factors in Perception." Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 43: 142-154. Prince-Gibson, E., & Schwartz, S.H. (1998). “Value Priorities and Gender.” Social Psychology Quarterly, 61: 49-67. PUBLIC-SECTOR MANAGERIAL VALUES: AND JAPAN UNITED STATES, CANADA, 173 Ralston, D.A., Holt, D.H., Terpstra, R.H., & Yu, K.C. (1997). “The Impact of National Culture and Economic Ideology on Managerial Work Values: A Study of the U.S., Russia, Japan, and China.” Journal of International Business Studies, 18: 107-177. Rokeach, M. (1968). Beliefs, Attitudes and Values. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Rokeach, M. (1973). The Nature of Human Values. New York: The Free Press. Rokeach, M. (Ed.). (1979). Understanding Human Values: Individual and Societal. New York: The Free Press. Rokeach, M., & Ball-Rokeach, S. J. (1989). “Stability and Change in American Value Priorities 1968-1981.” American Psychologist, 44: 775-784. Rokeach, M., Miller, M.G., and Snyder, J.A. (1971). “The Value Gap between Police and Policed.” Journal of Social Issues, 27: 155– 171. Sagiv, L. & Schwartz, S.H. (2000). “A New Look at National Culture: Illustrative Applications to Role Stress and Managerial Behavior.” In N.M. Ashkanasy, C. P. M. Wilderom, & M. F. Peterson (Eds.), Handbook of Organizational Culture & Climate (pp. 417-435). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Schmidt, W.H., & Posner, B.Z. (1987). “Values and Expectations of City Managers in California.” Public Administration Review, 47: 404-409. Schneider, B. (1987). “The People Make the Place.” Personnel Psychology, 40: 437-453 Schneider, B., Goldstein, H.W., and Smith, D.B. (1995). “The ASA Framework: An Update.” Personnel Psychology, 48: 747-773. Schwartz, S.H. (1992). “Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Theoretical Advances and Empirical Tests in 20 Countries.” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25: 165. 174 CONNOR, BECKER, MOORE & OKUBO Schwartz, S.H., & Bardi, A. (2001). “Value Hierarchies across Cultures: Taking a Similarities Perspective.” Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology, 32: 268-290. Schwartz, S.H., & Bilsky, W. (1987). “Toward a Universal Psychological Structure of Human Values.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53: 550–562. Siegel, S., & Castellan, N.J., Jr. (1988). Nonparametric Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. Sikula, A.F. (1973). “The Values and Value Systems of Governmental Executives.” Public Personnel Management: 16-22. Stackman, R.W., Pinder, C.C, & Connor, P.E. (2000). “Values Lost: Redirecting Research on Values in the Workplace.” In N.M. Ashkanasy, C.P.M. Wilderon, and M.E. Peterson (Eds.), Handbook of Organizational Culture and Climate (pp. 37-54). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Stackman, R.W., Connor, P.E., & Becker, B.W. (Forthcoming). “Sectoral Ethos: An Investigation of the Personal-Values Systems of Female and Male Managers in the Public and Private Sectors.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. Tan, B.L.B. (2002). “Researching Managerial Values: A Cross-Cultural Comparison.” Journal of Business Research, 55: 815-821. Theodorson, G.A., & Theodorson, A.G. (1969). A Modern Dictionary of Sociology. New York, Cromwell. Tompkins, J.R. (2005). Organization Theory and Public Management. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. Van Wart, M. (1998). Garland. Changing Public Sector Values. New York: Williams, R. (1968). “The Concept of Values.” In D. L. Sills (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. New York: Macmillan and the Free Press. Williams, R. (1979). “Change and Stability in Values and Value Systems: A Sociological Perspective.” In M. Rokeach (Ed.), Understanding Human Values: Individual and Societal (pp. 1546). New York: The Free Press.