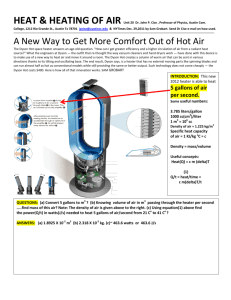

Word - Nieman Journalism Lab

advertisement