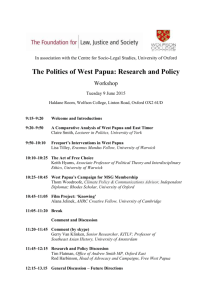

I. History of Human Rights Abuses in West Papua

advertisement