Engaging with the benefits of a diverse workforce

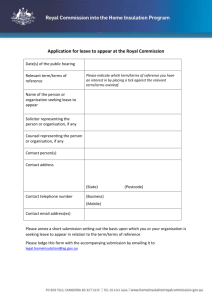

advertisement

Australian Command & Staff College The Fair Work Ombudsman’s view to managing a workforce Nicholas Wilson 1 with Lynda McAlary-Smith and Adam Rodgers 2 16 November 2012 Preamble 1. I begin by acknowledging the traditional owners of the land on which we meet, the Ngunnawal people, and pay my respects to Elders both past and present. 2. I would like to thank the Australian Command & Staff College for the invitation to speak here today. 3. I record that the views I express today are my own and do not necessarily reflect Government policy, and I take responsibility for any errors in the text. 4. I’ve been asked here today to share my views on current issues in Australian workplaces and alternative views to managing the workforce. In doing so, I will give you some context about the Fair Work system, what it does, and how its several elements fit together. I also plan to discuss a range of issues that my agency, the Fair Work Ombudsman, deals with on a day to day basis 5. I will also examine some workplace and management issues that my agency endeavours to observe as well as seek to raise awareness about. This includes topics such as leadership, discrimination, diversity as well as procurement and the fair work ethics involved in supply chains. 1 Fair Work Ombudsman 2 Executive Director, Education and National Employers and Director, Education P a g e |2 The Fair Work system, and the role of the Fair Work Ombudsman 6. The Fair Work Ombudsman was established on 1 July 2009 under the Fair Work Act. The Agency is one of two created by the Fair Work Act, the other of which is the national workplace relations tribunal, Fair Work Australia, whose head is The Honourable Justice Iain Ross AO. A later creation (formed by separate legislation) is Fair Work Building and Construction, headed by Leigh Johns, which has responsibility for workplace relations regulations for the major construction industry. 7. At its core, the role of the Fair Work Ombudsman is to promote harmonious, productive and cooperative workplace relations and ensure compliance with Commonwealth workplace laws3. 8. Our vision is to create fairer Australian workplaces. Working toward this vision, we interact with more than 3 million people a year – we advise; we assist; we educate; and we ensure compliance. 9. The Fair Work Act introduced significant legislative changes that impacted on the majority of Australian workplaces. These changes dealt with a number of important areas, such as, the introduction of new good faith requirements for workplace bargaining and ten National Employment Standards, which provide for a minimum safety net for employees.4 10. My Agency’s mandate is to build public knowledge of the Australian workplace relations safety net and enable employers and employees to empower themselves to resolve their own disputes. We recognise that the greatest public good is for Australians to be aware of their rights and obligations and to be given the confidence that their rights and obligations can be accessed. 3 Fair Work Act 2009 – Section 682 (1) 4 Sections 124-125 of the Fair Work Act Australian Command and Staff College 16 November 2012 P a g e |3 11. In raising awareness of these rights and obligations, one of the more traditional methods of engagement with employers has been that of our targeted campaigns. Our targeted campaigns team analyses our own internal data and intelligence from the broader community to determine what industry, profession or location should be the focus of our targeted educative and compliance campaigns. These campaigns are either national, state/territory based or regional. 12. The overarching philosophy of these campaigns is to have a positive impact on the long-term behaviour of employers by combining education with compliance activities. These campaigns are an opportunity to drive cultural change within workplaces by equipping them with the right information and tools to create compliant and respectful workplaces. 13. As positive as our message is during these campaigns, it is also an opportunity to detect where employers are getting it wrong; some intentional, most unintentional, and help them to try and fix any problems. In the 2011-2012 financial year, we conducted 4 national campaigns and 22 state/territory campaigns5. This resulted in over 6,500 individual time and wage audits being conducted with over $6 million in underpaid wages recovered for almost 4,000 employees. I am pleased to say that the overwhelming majority of issues we identified were resolved voluntarily. 14. ln addition to our interactions with individual workplaces through our targeted campaigns, our primary points of contact for employers and workers are through our website fairwork.gov.au and the Fair Work Infoline. We have direct communication with customers through both of these channels. In the last financial year, we: a. answered almost 700,000 phone calls b. responded nearly 40,000 email enquiries c. conducted over 48,000 live chats via fairwork.gov.au. 5 National campaigns: Retail, Security, Clerical and Vehicle. Australian Command and Staff College 16 November 2012 P a g e |4 15. We have a wealth of information available on fairwork.gov.au, and we’re always looking at what else can be done. Moving forward, our aim is to increasingly empower workers and employers with the skills to be able to resolve problems or concerns at their own workplace level. This sees the evolution of our educative role: we’re moving beyond educating workplace participants on specific rights and entitlements; we are now moving towards skilling both employers and employees to effectively resolve workplace disputes, lessening the need for our intervention. Managing workplace issues 16. The Fair Work Ombudsman encourages all employers and employees to attempt to resolve workplace relations matters in house. Although your workplace may not be governed by the same legislation that we enforce, this is principle remains the same. 17. Research undertaken by the Department of Industry, Innovation, Science, Research and Tertiary Education has shown self-resolution mechanisms provide benefits to employers, employees and the economy as they: a. Improve employee engagement b. Are more cost effective and less formal than investigation, arbitration and especially litigation, and they c. Help maintain and improve the employment relationship6. 18. There are additional steps an employer can take to minimise and resolve disputes in the workplace, as well as enabling disputes to be dealt with when they do arrive. These include: a. Encouraging the open and professional expression of opinions by staff and management 6 Department of Innovation, Industry, Science & Research ‘Resolution of small business disputes options paper’, 2011 Australian Command and Staff College 16 November 2012 P a g e |5 b. Recognising the importance of how people feel about issues c. Listening to what people have to say d. Focusing on interests rather than positions and personalities e. Making sure you have clear discipline, grievance and dispute handling procedures in place.7 19. I know that some of these recommendations may be easier said than done, but managers will find that these measures will work towards limiting the need for third party involvement in workplace disputes. 20. For our Agency it becomes an issue of significant concern when an employer or employer representative is being wilfully negligent of their responsibilities and demonstrates no intention of doing the right thing. As I will discuss later, knowing your responsibilities and boundaries is an important part of effective people management. 21. I believe this applies to any workplace; as well as yours. I understand that the Defence Force has its own internal processes to deal with disputes as well as external bodies they answer to when issues cannot, or should not, be resolved in house. 22. In house dispute resolution is an issue I believe deserves far greater attention. The Fair Work Ombudsman is working toward educating workplace participants to equip them with the knowledge and confidence to be able to resolve issues without external involvement. Workplace compliance trends 23. As I’ve said, my job is to make sure that employers are complying with the Fair Work Act so that workers are receiving their safety net rights and entitlements. The work 7 ACAS – Disputes and conflict in the workplace Australian Command and Staff College 16 November 2012 P a g e |6 that we do in this capacity gives us great insight into trends of non-compliance in the broader workforce. 24. Based on complaints received in the 2011-2012 financial year, we know that the accommodation and food services industry and the retail industry are among the more problematic industries operating in Australia. 25. The vast majority of the complaints we receive from these industries relate to the underpayment of employee wages and conditions. This is sometimes due to wilful negligence on the employer’s part, though it is more often a result of oversight by an employer or manager and is able to be resolved through voluntary compliance. 26. Voluntary compliance means that the person who has breached the legislation remedies the issue willingly at the request at one of our Fair Work Inspectors. I am pleased to say that we achieve this outcome in the majority of complaints received. 27. Voluntary compliance presents our inspectors with the opportunity to educate these employers to prevent this type of thing from happening again. Of course the ideal outcome for us would be employers and managers being aware of their obligations from the outset. I know this is not an easy task, but I believe it is part of being a good leader and a strong manager. Knowing your responsibilities and obligations is important in any role. Being naïve or ignorant to something that is required of you will never work in your favour. This is something else I hope you take away from today: make it your purpose to know what’s expected of you from every possible angle. 28. I know, for example, that for private sector employers, there is a need to contend with the Fair Work Act, taxation legislation, workplace health and safety and more. 29. Of course, the Defence Force faces similar and indeed higher levels of regulation. There are always those policies and procedures that you need to adhere to, to ensure your business, operational group, etc is running efficiently and your staff knows that you are diligent with matters that affect them. As leaders, we are often also required to consider events and obligations further down a chain of command. Australian Command and Staff College 16 November 2012 P a g e |7 Leadership in the public sector context 30. The idea that we are judged by our actions rather than our intentions is by no means new. We are all aware that the public sector, and Defence in particular, is no stranger to public scrutiny. We answer to the Australian public and they expect a lot from us. It is essential that we live up to these standards. In this sense particularly, it is our actions that count, rather than our intentions. 31. I see this philosophy as another essential element of strong leadership. Action will always be regarded higher than intent. This applies most of all to managers and leaders. 32. In an agency sense, leadership is the preparedness to have the organisation become as high performing as it possibly can, given the constraints of legislation and resources. Notwithstanding these constraints, which are obviously real in the Australian public sector context, an agency showing leadership can be expected to be constantly testing these boundaries, with a view to expand them. The conversation becomes one of “with these additional resources, or with this change to our legislation, or with this change to our operating procedures, we can achieve even better”. 33. As an individual, leadership is not dissimilar to the agency leadership construct – a preparedness to go as far as possible within existing constraints, coupled with a preparedness to test the appetite for going beyond. 34. “Change” is not especially relevant to leadership, and is certainly not the driver of leadership – rather performance is the driver. Perhaps change is needed to achieve performance, and perhaps it is not. 35. In my agency, admittedly there has been a constancy of change, some of which is structural, some legislative, and some aimed at improving performance. The organisation and staff have undergone significant transformations every 6 to 12 months or so. 36. Leadership may be better thought of as a “brand” that might be expected of a number of people in any given organisation and the Defence Force is an exemplar of Australian Command and Staff College 16 November 2012 P a g e |8 this. The idea of there being a leadership brand is articulated by Dave Ulrich and Norm Smallwood in this way; a. “Some executives just don’t get it. They may say they believe in leadership, but they don’t act like it. When times are good, they invest in leadership and proclaim themselves good corporate citizens, but in tough times, leadership investments are one of the first budgets they cut. What they really need is to understand how an investment in leadership will help them reach their own goals and their company’s strategies- and how lack of leadership inhibits growth and confidence and diminishes value. b. “Executives who do get it not only say leadership matters, they demonstrate their commitment in action that is consistent through good times and bad”. 8 37. The proposition develops that leadership is something that must be practiced and worked upon. Leadership should be enduring, and not switched on for special occasions; instead it should be a brand that is identified with the organisation. 38. Leadership is not singular. While I might be a leader in my organisation, I am not the only leader, and could not achieve the performance our organisation has without there being many leaders. Leaders are activist, and leadership is personal. The characteristics we might see in leaders include people who: a. Understand the organisation and its purpose b. Are motivated c. Have excellent technical skills d. Have excellent team supervision skills e. Are resilient and are able to withstand pressure f. Are open to doing something novel or different to the “business as usual” construct g. Are part of a management team that is not interested in the status quo 8 Ulrich D. and Smallwood N., Leadership Brand, Harvard Business School Press, Cambridge MA, 2009, p29 Australian Command and Staff College 16 November 2012 P a g e |9 39. You can translate the idea of a corporate leadership into a personal leadership brand in several ways. Ulrich and Smallwood suggest you should ask yourself what you personally stand for and ask yourself how you will demonstrate that point of difference to others. You reinforce your leadership brand by periodically assess yourself; ensuring you invest in yourself; and measure your progress against your objectives of a leadership brand.9 40. My reflection is that at any given time, up to 20% of the organisation’s staff might qualify as leaders. Strong leadership cannot be put down to one skill or trait, it is the culmination of a number of factors. 41. It is also about action. No one has ever received praise for something they intend to do. A leader can play a big role in creating a positive, productive workplace culture. Contractors and procurement chains 42. Similar to other government bodies and large and small private sector employers, the Defence Force has involved itself a great deal in supply chains and procurement. 43. Like many large private and public sector employers, there is without question an invisible workforce that works around the Defence Force – cleaners, truckies and IT professionals are just a few. They work for and around you though often have very different pay arrangements. Sometimes these arrangements are unlawful. For those of you going on to managerial or high-ranking positions, you will need to be extremely familiar with the procurement practices of the Defence Force and abide by them faultlessly. 44. Procurement and supply chain problems are becoming increasingly visible in the private sector. The Fair Work Act has introduced new provisions about supply chain responsibility. These provisions create a scenario where a person or business involved in a contravention can be held as liable for the contravention as the primary 9 ibid, from p211 Australian Command and Staff College 16 November 2012 P a g e | 10 party. That is to say, if you procure the services of a business that underpays their staff, you may be held equally liable as that business for the underpayments. 45. An example of this is our current litigation against both Coles Supermarkets and a trolley collecting company in South Australia. Between January 2010 and July 2011, Coles contracted a trolley collecting company to work at several shopping centres around Adelaide. This trolley collecting company then sub-contracted part of the work to a third party. We have evidence to suggest that this third party collectively underpaid four employees up to $149,35010. 46. Although Coles appears twice removed from the party directly responsible for this gross underpayment, by virtue of these new provisions of the Fair Work Act, we intend to prove that they knowingly involved themselves in this contravention. 47. It’s not just that the Fair Work Act is encouraging businesses to act ethically in supply chain matters, the community is demanding it, and business is responding. For instance, Westpac has, at its own initiative, introduced comprehensive measures and polices that ensure its own procurement practises help its suppliers meet Westpac’s social, ethical and environment goals11. 48. I believe that this responsibility lies with everyone that can have an impact on the politics of supply chains. The Australian public holds organisations accountable by the company that they keep, by the standards that they expect from their suppliers, so this is more than an ethical issue. 49. I encourage you to consider this; when tendering for work of any type, it’s important to inform yourself of what obligations your vendors should be meeting when it comes to minimum rates of pay. Even if you don’t have a statutory obligation there 10 FWO Media release 11 http://www.westpac.com.au/about-westpac/sustainability-and-community/sustainability- action/suppliers/sustainable-supply-chain/ Australian Command and Staff College 16 November 2012 P a g e | 11 is, at the very least, an ethical obligation to ensure those potentially vulnerable workers in the supply chain are receiving their minimum wages and entitlements. 50. For me procurement practices are a very real, tangible issue in Australian workplaces, and present an ongoing challenge for leaders in all sectors. Sham contracting 51. Care also has to be taken in categorising workers as “contractors”. Not every worker called a “contractor” is actually a contractor, and many will be employees. An independent contractor is someone who is self-employed and contracts their services to clients, such as other businesses. Independent contractors aren’t employees and have different rights. 52. It’s important to understand the difference between independent contractors and employees and to give them their correct entitlements. Providing an ABN or an invoice for payment may not mean a worker is an independent contractor. Labelling people as independent contractors or getting them to sign contracts which state they are doesn’t mean this either. There are a number of factors that need to be considered. 53. Misrepresenting or disguising an employment relationship as an independent contracting arrangement is known as ‘sham contracting’ and is against the law. Dismissing or threatening to dismiss an employee to engage them as an independent contractor is also against the law. Workplace rights and “General Protections” 54. Another important change was the introduction of rights enshrined as General Protections. That is, protections that prohibit employers from adversely treating or impacting a person’s employment based on discriminatory grounds including marital status, sex, sexual orientation, family or carer’s responsibilities or pregnancy. These provisions also extend to provide protections for certain workplace rights including the right to engage in lawful industrial activities. Australian Command and Staff College 16 November 2012 P a g e | 12 55. The introduction of these protections into the federal workplace law has been an important step in working towards a society where all workplace participants will be free from discrimination. We all have a role to play in ensuring that our workplaces are free from discrimination. As senior leaders you should ask yourself, what type of role do you want to play in creating a workplace that is free from discrimination? And how do you encourage exemplary behaviour from those around you? I suspect you have to ask yourself these questions in some very tough situations. Engaging with the benefits of a diverse workforce 56. I see untold value in a diverse workforce and I am not the only one. In a survey carried out by HR Magazine, 82 per cent of employers said that diversity and equality were either core to a business, a top priority or important to them12. 57% of these employers told that they had a diversity strategy in place and a fifth undertook regular diversity monitoring. I was pleased, though not surprised to see the Department of Defence’s membership with the Diversity Council of Australia. I believe it is important that we as public servants lead by example with matters as important as this. 57. Drawing on skills and experience from staff with different ethnic, educational and social backgrounds opens up a wealth of possibility to encourage innovation and creativity. Drawing from a diverse workforce also puts you in a position where you can interact with a broad client base. 58. The Australian Public Service Commission has also stated that organisations that capitalise on employee diversity have productive and fulfilling workplaces which help them attract and retain employees. This also leads to savings in recruitment and training costs, as well as maintaining corporate knowledge and expertise13. 12 Employers without a diversity strategy are losing out - ACAS 13 APSC Guidelines on workplace diversity Australian Command and Staff College 16 November 2012 P a g e | 13 59. A diverse workforce will also reflect the expectations of the government and the community about a fair, inclusive and productive public service. This is something I would recommend you would consider as commanding officers and managers. Diversity in the workplace will always work in your favour. 60. These issues share a common underlying theme. Be it creating a diverse workforce, or ensuring ethical practices in supply chains, what’s important are the actions of those involved in the decision making processes, rather than intentions. 61. I strongly encourage you to consider the issues I’ve raised here today. Diligence in procurement can positively impact a great number of workers the whole way down a supply chain. I would also encourage you to consider the benefits of diversity. It is these types of practices that make an organisation stand out as an exceptional employer. Leading ... you within the system 62. You, like I, will need to be a leader within a highly organised and bureaucratic organisation. The tendency for managers within such organisations is to lead the managing of specialist activities up to those who are specialists. 63. I suggest that you need to watch for the occasions on which that tendency could work against your need to be a leader. The group of people you lead will watch you and assess you on everything you do – including those occasions in which you don’t overtly do anything. And, of course that is a dilemma for any aspiring leader – how on earth can you lead where you are impacted so much from other parts of the organisation. 64. The answer of course, is in how you advocate and negotiate as best you can with the rest of the organisation, and the people of influence within it. 65. To finish up today, I would like to commend each of you here today in taking such an important step in your future as a leader within the Defence Force. I recognise that each of you are making a personal commitment in undertaking this year long program, and I thank you for your time. Australian Command and Staff College 16 November 2012