Sonia Jones Case Study - Bowmanville High School

advertisement

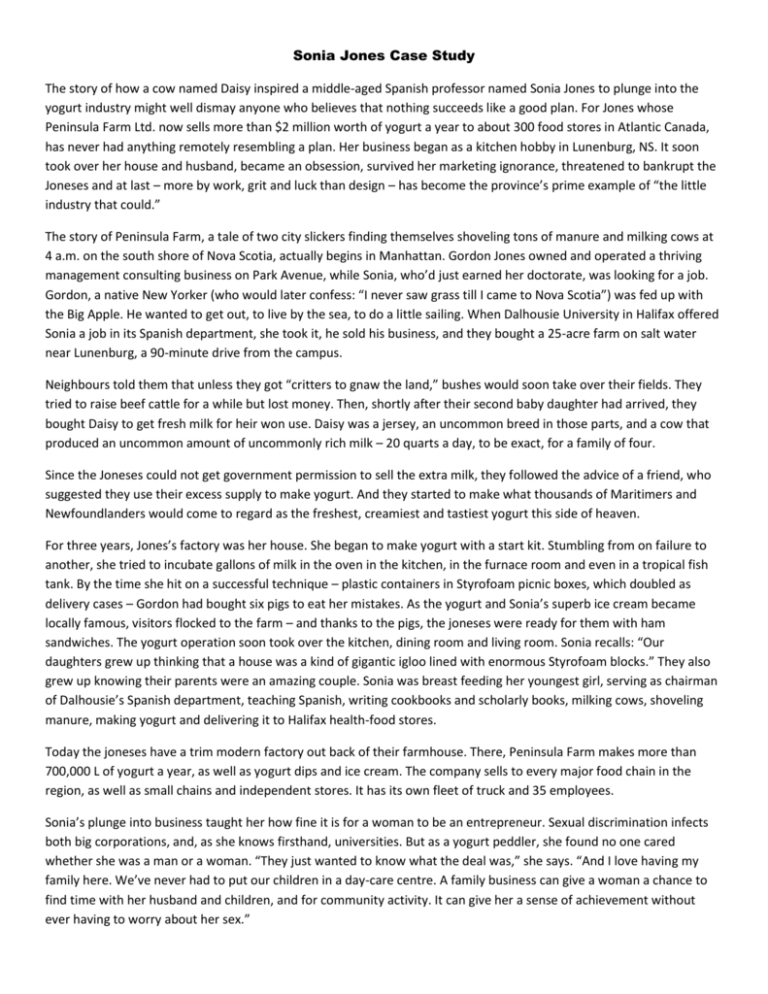

Sonia Jones Case Study The story of how a cow named Daisy inspired a middle-aged Spanish professor named Sonia Jones to plunge into the yogurt industry might well dismay anyone who believes that nothing succeeds like a good plan. For Jones whose Peninsula Farm Ltd. now sells more than $2 million worth of yogurt a year to about 300 food stores in Atlantic Canada, has never had anything remotely resembling a plan. Her business began as a kitchen hobby in Lunenburg, NS. It soon took over her house and husband, became an obsession, survived her marketing ignorance, threatened to bankrupt the Joneses and at last – more by work, grit and luck than design – has become the province’s prime example of “the little industry that could.” The story of Peninsula Farm, a tale of two city slickers finding themselves shoveling tons of manure and milking cows at 4 a.m. on the south shore of Nova Scotia, actually begins in Manhattan. Gordon Jones owned and operated a thriving management consulting business on Park Avenue, while Sonia, who’d just earned her doctorate, was looking for a job. Gordon, a native New Yorker (who would later confess: “I never saw grass till I came to Nova Scotia”) was fed up with the Big Apple. He wanted to get out, to live by the sea, to do a little sailing. When Dalhousie University in Halifax offered Sonia a job in its Spanish department, she took it, he sold his business, and they bought a 25-acre farm on salt water near Lunenburg, a 90-minute drive from the campus. Neighbours told them that unless they got “critters to gnaw the land,” bushes would soon take over their fields. They tried to raise beef cattle for a while but lost money. Then, shortly after their second baby daughter had arrived, they bought Daisy to get fresh milk for heir won use. Daisy was a jersey, an uncommon breed in those parts, and a cow that produced an uncommon amount of uncommonly rich milk – 20 quarts a day, to be exact, for a family of four. Since the Joneses could not get government permission to sell the extra milk, they followed the advice of a friend, who suggested they use their excess supply to make yogurt. And they started to make what thousands of Maritimers and Newfoundlanders would come to regard as the freshest, creamiest and tastiest yogurt this side of heaven. For three years, Jones’s factory was her house. She began to make yogurt with a start kit. Stumbling from on failure to another, she tried to incubate gallons of milk in the oven in the kitchen, in the furnace room and even in a tropical fish tank. By the time she hit on a successful technique – plastic containers in Styrofoam picnic boxes, which doubled as delivery cases – Gordon had bought six pigs to eat her mistakes. As the yogurt and Sonia’s superb ice cream became locally famous, visitors flocked to the farm – and thanks to the pigs, the joneses were ready for them with ham sandwiches. The yogurt operation soon took over the kitchen, dining room and living room. Sonia recalls: “Our daughters grew up thinking that a house was a kind of gigantic igloo lined with enormous Styrofoam blocks.” They also grew up knowing their parents were an amazing couple. Sonia was breast feeding her youngest girl, serving as chairman of Dalhousie’s Spanish department, teaching Spanish, writing cookbooks and scholarly books, milking cows, shoveling manure, making yogurt and delivering it to Halifax health-food stores. Today the joneses have a trim modern factory out back of their farmhouse. There, Peninsula Farm makes more than 700,000 L of yogurt a year, as well as yogurt dips and ice cream. The company sells to every major food chain in the region, as well as small chains and independent stores. It has its own fleet of truck and 35 employees. Sonia’s plunge into business taught her how fine it is for a woman to be an entrepreneur. Sexual discrimination infects both big corporations, and, as she knows firsthand, universities. But as a yogurt peddler, she found no one cared whether she was a man or a woman. “They just wanted to know what the deal was,” she says. “And I love having my family here. We’ve never had to put our children in a day-care centre. A family business can give a woman a chance to find time with her husband and children, and for community activity. It can give her a sense of achievement without ever having to worry about her sex.” Asked if she has a philosophy of business, Jones, ever the writer, worries about clichés. “Well, it’s so Girl Scouty,” she says. “It’s just that honesty really is the best policy. That is why we’re in the Maritimes. But we really are in love with this place. Maybe I’m naive, but I can’t get over the honesty of business dealings down here. This really is a wonderful place to do business. People here have these old-fashioned virtues. “Oh, God, I know that’s a cliché, but it’s true. Here, you’re aware of people helping one another, rather than doing them in. “It’s the quality of life, and yes, that’s another cliché, but it’s healthier here. It’s more conducive to happiness. I enjoy dealing with people I respect and like and admire, and that’s why we’re here, and that’s why we’re going to stay.”