paper - African Development Bank

advertisement

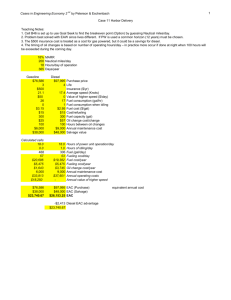

1 Overcoming Non-Tariff Barriers to Regional Trade through Stakeholder Forums: Normative and Empirical Dimensions Abstract Despite the issue of non-tariff-barriers to trade (NTBs) receiving prominence at the highest political and administrative levels of the East African Community (EAC), which is widely held up as a remarkably successful example of regional cooperation, and despite the creation of diverse stakeholder forums that are intended to stimulate public-private sector collaboration around overcoming NTBs, the problem persists. The time has surely come to explore the normative claims that stakeholder collaboration will deliver benefits beyond those provided by conventional state-led legal or administrative actions. Drawing on empirical insights that flag issues of representation, communication, reforms and inclusivity, the paper argues that despite stakeholder forums being important innovations, playing their optimal role within dynamic and complex cross-border trade settings requires policymakers to recognise their inherent limitations, and the considerable opportunity for further refinements through regulatory or other mechanisms. 1.0 Introduction It is acknowledged that non-tariff barriers to trade (NTBS)—or unjustified or improper application of measures that render importation or export of products difficult—not only present a concrete and pressing problem to many regional trading areas across the world, but they also challenge the capacity of traditional state structures of governance. Traditionally, the emphasis on resolving NTBs has been through the use of formal, largely hierarchical principal-agent accountability relationships where a legislature (the principal) confers on an administrative agency (the agent) responsibility for the performance of particular tasks, with a duty to explain, justify, and be held accountable for its efforts to overcome NTBs. In recent years, however, these traditional reliance on centralised authority has been supplemented by 'new' arrangements through which public-private dialogue occurs, and which are intended to serve as entry points for the private sector to flag their issues and concerns in collaboration with technical experts, policymakers, and other expertise. These capitalise upon the unique capacities of multiple public or private actors who collaborate through horizontal relationships, for instance among national agencies operating with their counterpart agencies across national borders, as well as through downward relationships, where stakeholders are also made accountable to their respective sectors or business associations. Although these stakeholder forums are explicitly or implicitly believed to deliver effectiveness, legitimacy, and democratic benefits that surpass those provided by conventional approaches led by different tiers of government and/or government agencies, such claims cannot be validated in the absence of appropriate empirical work—which is presently thin on the ground—with emphasis on their inherent limitations, as well as reflecting upon the considerable opportunity for further refinements that would enable them to play their optimal role in terms of overcoming NTBs within dynamic and complex cross-border trade settings. 2 It is here that an important caveat must be included. A conscious effort is taken in this paper not to discuss NTBs from the allied and complementary perspectives of law, economics and political science. While these are important issues, suffice it to say, they have received attention both from the media as well as within the academic literature. Rather the paper’s evaluation of stakeholder arises as follows. The first part explores key concepts, which are subsequently highlighted in the elaboration of the institutional framework established within the EAC to monitor and eliminate NTBs. This is followed with a review of some specific multi-stakeholder forums mechanisms, which draws upon respondents’ opinions regarding their inherent limitations, as well as reflecting upon the considerable opportunity for further refinements that would enable them to play their optimal role in terms of overcoming NTBs. 2.0. Background and Context 2.1. East African Economic Integration in Perspective Economic integration in may be understood as an attempt to link together the economies of two or more countries. Through removing tariffs and other barriers to trade, the participating countries hope to promote economic integration and expand opportunity for their respective citizens. Perhaps due to the close geographical proximity, shared historical links and cultural links, East Africa has also enjoyed a long history of co-operation under successive regional integration arrangements: 1917: Customs Union between Kenya and Uganda—which the-then in Tanganyika later joined in 1927; 1948-1961: East African High Commission; 1961-1967: East African Common Services Organization; 19671977: and the East African Co-operation, 1993-2000. The EAC Treaty establishing the community was signed on 30 November 1999 and entered into force on 7 July 2000 following ratification by the original three partner states – Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. Burundi and Rwanda became full members of the EAC on 1 July 2007. The joining of Burundi and Rwanda into the EAC trade integration process further widened up the market to 135.5 million people, with regional GDP increasing from US$42.4 billion in 2006 to 74.5 billion in 2009 and which was expected to reach $80 billion in 2012. 1 The EAC today is a regional intergovernmental organization, with a headquarters and Secretariat in Arusha, Tanzania. South Sudan has made an application to join the EAC. 2.3. The Institutional Framework In line with article 5(2) of the EAC Treaty, the Partner States undertook to create a regional trade arrangement (RTA) with four key milestones. Article 5(2) provides that the Partner States undertake to establish among themselves and in accordance with the provisions of the Treaty, a Customs Union, a Common Market, subsequently a Monetary Union and ultimately a Political Federation. Special Correspondent ‘Kenya’s Private Sector best in EA—the country can easily produce goods that the region imports’ The East African (Nairobi, 8-14 June 2013) 47 1 3 The Customs Union (CU) became operational in 1 January 2005 (although Rwanda and Burundi later joined in 1 July 2009). In a CU, Partner States agree to dismantle barriers to trade in goods and services among themselves, and establish a common external tariff (CET) policy whereby imports from non-members are subject to the same tariffs when imported. Some of the benchmarks for the EAC Customs Union, which include elimination of internal tariffs, free circulation of goods and joint modalities for customs revenue collection and sharing and harmonized domestic taxes, are provided for under the East African Community Customs Management Act of 2006. As the following tables will show, the CU has resulted in increased Kenya’s exports and imports from EAC countries. This reflects greater openness of trade in the region. Between 2008 and 2012, Kenya’s exports have significantly increased, particularly to Tanzania and Uganda. However, significant growths in exports to Rwanda and Tanzania have also been recorded. Table 1: Exports from Kenya to EAC Countries, 2008-2012 Country Tanzania Uganda Rwanda Burundi Total, EAC (KES ‘000) 2008 2009 Total Exports 2010 2011 2012 29,223,947 42,285,352 8,953,198 3,479,476 83,941,972 30,086,582 46,239,885 9,535,976 4,597,172 90,459,615 33,211,109 52,107,583 10,535,060 5,458,011 101,311,763 46,036,163 67,450,115 16,151,363 5,308,763 134,946,405 41,743,395 75,953,923 13,553,558 5,903,760 137,154,635 Source: Economic Survey 2013, Kenya National Bureau of Statistics The following table will show that exports from the EAC countries to Kenya have also registered a significant increase between 2008 and 2012. Table 2: Exports from EAC Countries to Kenya, 2008-2012 Country Tanzania Uganda Rwanda Burundi Total, EAC 2008 2009 7,265,089 5,221,189 25,327 78,159 12,589,764 7,809,234 4,426,263 240,070 92,653 12,568,221 (KES ‘000) Total Imports 2010 2011 10,548,967 9,226,647 430,122 144,855 20,350,591 15,670,393 10,337,155 422,246 468, 845 26,898,639 2012 14,401,599 15,332,810 822,286 310,424 30,857,118 Source: Economic Survey 2013, Kenya National Bureau of Statistics The above figures indicate that while Tanzania and Uganda are the greatest beneficiaries of exports into Kenya in the period 2008-2012, both Rwanda and Burundi have also registered significant growth in exports. The key message from both tables, thus, is that the gains from liberalizing trade between countries can be substantial. By creating a larger marketplace where borders no longer matter, and where goods can freely move without hindrance, national income can grow more rapidly. 4 Finally, it should be noted that the next stages of economic integration are not yet in operation. The stage of economic integration, which follows a CU is the Common Market. This essentially provides for ‘Four Freedoms’, namely the free movement of goods; labour; services; and capital. Partner States must also be prepared to cooperate in monetary, fiscal and employment policies. The Protocol for the Establishment of the EAC Common Market signed was signed on 20 November 2009. The next stage – Monetary Union – would bring a single currency to the region, and agreement on the Monetary Union protocol was planned for 2012, but is behind schedule. The final stage – Political Federation – would likely bring a centralized president and parliament, and is planned for 2015. Given delays in implementation of both the Customs Union and Common Market, it is expected that the Monetary Union and Political Federation protocols, might be postponed further. 3.0 Framework for NTB Monitoring in the EAC 3.1 Classifying and Understanding NTBs Non-Tariff Barriers (NTBs) refer to restrictions that result from prohibitions, conditions, or specific market requirements that make importation or exportation of products difficult and/or costly. NTBs also include unjustified and/or improper application of Non-Tariff Measures (NTMs) such as sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures and other technical barriers to Trade (TBT). NTBs arise from different measures taken by governments and authorities in the form of government laws, regulations, policies, conditions, restrictions or specific requirements, and private sector business practices, or prohibitions that protect the domestic industries from foreign competition.2 3.2. The Legislative Context Under Article 13(1) of the EAC Customs Union Protocol, Partner States agreed to eliminate remaining NTBs and refrain from imposing new ones. The Customs Union Protocol also provides for the development of a new mechanism to identify, monitor and eventually remove NTBs in collaboration with the East African Business Council. This mechanism was adopted through wide consultations with the policy-makers, heads of agencies responsible for enforcing trade-related requirements, business associations, clearing and forwarding associations and representatives of key businesses that have substantial activities within the original EAC countries—Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania. The Mechanism was adopted by the Council of Ministers in the year 2006, and it required the EAC Member States to immediately establish National Monitoring Committees (NMCs) on NTBs. This means that Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania established NTB Committees in 2006, while Rwanda and Burundi launched theirs’ in October 2008. In order to facilitate the process of eliminating NTBs, the mechanism was based on two key principles, namely: (1) goodwill and commitment at both the political and technical levels to implement aspirations of the EAC Treaty; (2) Enshrinement of the Legal and Regulatory Framework governing the integration process. Regular 2 Olivier Cadot, Mariem Malouche and Sebastian Saez Streamlining Non-Tariff Barriers-A toolkit for policymakers (World Bank, Washington DC, 2012) 9-35 < https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/6019> Accessed: 25 June 2013 5 monitoring of council decisions was facilitated at both the national and EAC levels, and was conducted at various stages by relevant trade officials. Also, to ensure efficient implementation of the Mechanism, Partner States undertook key activities that included awareness-creation and sensitization of key stakeholders, regular monitoring of Council decisions and allocation of sufficient and timely resources for NTB activities. The NTB structure consists of public and private sector focal points, as well as National Monitoring Committees (NMCs). NMCs comprise all government ministries and departments, private sector organisations, trade associations, and major exporters and importers who are appointed to facilitate resolution of reported barriers against their countries as well as barriers imposed against their businesses. The specific role of an NMC is to receive copies of NTB complaints from businesses. The expectation is that they would originate from drivers of commercial vehicles, validated by their line managers, and forwarded by the top management to their respective business associations or chambers of commerce. Such complaints would be sent to the line ministry or agency by business associations, chambers of commerce and individual businesspeople. Once received, discussions should be held as to whether actions taken by the line ministry or agency responsible for enforcement are sufficient. If necessary it may initiate bilateral discussions with counterpart NMCs in the other partner states regarding NTBs that may be of a cross-border nature, and initiate an elimination process. Where necessary, equivalent agencies responsible for enforcing trade regulations will be brought together to negotiate a harmonisation process, if the NTB in question is in form of varying trade requirements between EAC states. Bilateral dispute resolution will always be used before every NTB cases are referred to the EAC Secretariat for policy action; Following from this, the NMC is required to forward information on national actions taken by line ministry or agency responsible for acting on an NTB to the EAC Secretariat through the Director of Trade for information and onward dissemination to the other Partner States’ NMCs. Next, it is required to disseminate information on actions taken on reported NTBs received from the other two Partner States through the EAC Secretariat to the business associations and chambers of commerce for onward transmission to the business community. If this fails, it must refer cases to the EAC Secretariat, where no satisfactory solution in form of a planned review, amendment or withdrawal has been proposed by the agency responsible for enforcement within one calendar month from the date of reporting. Finally, it should hold an annual regional forum where members can share experiences on the NTB elimination process, review achievements made, challenges faced and necessary initiatives for improving on the efficiency of the Monitoring Mechanism Findings from the two most recent reports3 indicate that the respective EAC NMCs score poorly in terms of effectiveness. As of September 20124, 33 NTBs remained unresolved; 10 new NTBs were reported; and 30 NTBs were reported as resolved. 3 These reports on the status of the EAC Time Bound Programme on elimination of identified NTBs are prepared pursuant to Article 13(2) of the Customs Union Protocol 4 The EAC Time Bound Programme on elimination of identified NTBs was updated during the 8 th EAC Regional Forum on elimination of NTBs which was held from 17th-19th September 2012, Entebbe, Uganda. 6 Further, as of March 2013 5 , 33 NTBs remained unresolved; 7 new NTBs were reported; and 46 NTBs were recorded as resolved. These key observations about the nature of NMCS then pave the way for an understanding of the contributions of stakeholder forums towards addressing the problem of NTBs within the EAC. 4.0 Mechanisms used in Overcoming NTBs in EAC 4.1. Trade Facilitation and Overcoming Institutional Barriers to Regional Trade The problems, which contribute to unnecessary costs and delays, are well documented: lack of verification sheds and parking yards at border posts;6corruption, for instance at police road blocks and weighbridges7; congestion and costly delays8 at the Ports of Mombasa due to a large number of institutions with overlapping jurisdictions, and poor infrastructure; 9 long queues at weighbridges—sometimes as long as 20 km—which arise, variously, due to corruption, inefficiency and inconsistent application of new rules on load measurements; 10 and non-harmonized sanitary and phyto-sanitary (SPS) requirements and arbitrary technical standards11 Stakeholder participation is an integral part of government efforts to facilitate trade and overcome institutional barriers to cross border trade..12 This has been seen in at least two respects. First, is the establishment of Joint Border Committees (JBCs). These have been established at 16 border posts in East Africa, drawing on representation from the local business community, they have made invaluable contribution towards efficient border procedures devoid of duplication, and delays. Their role has also been institutionalised within the development of the One Stop Border Posts (OSBP), which are presently being institutionalised in the One-Stop Border Posts Bill 2012. In addition the practice of holding regular stakeholder meetings is an established feature, for instance at Mombasa Port. These bring together the Kenya Ports Authority, operators of container freight stations, various government agencies, and key stakeholders drawn from the transport sectors e.g. railways and road transporters. 4.2 Proposed Legally Binding Mechanism on eliminating NTB The EAC Time Bound Programme on elimination of identified NTBs was updated during the 10 th EAC Regional Forum on elimination of NTBs which was held from 6th-9th March 2013, Bujumbura, Burundi. 6 Reuben Olita ‘Malaba clearing agents attack URA’ New Vision (Kampala, 27 May 2013) 26; 7 Transparency International-Kenya ‘Bribery as a non-tariff barrier to trade—A survey of East African Trade Corridors’ (2012) < http://www.trademarkea.com/resource-centre/publications> Accessed: 23 June 2013 8 According to the Shippers Council of East Africa, logistics costs in East Africa are amongst the highest in the world, which seriously cripples business and renders the region uncompetitive. They account for about 42% of the total cost of importing, while costs associated with delays represent about 23% of the total import process cost. Source: presentation made to the East African Business Council National Chapter Sensitization Meeting on 24 May 2013 at the Panafric Hotel Nairobi <http://www.kepsa.or.ke/index.php/resource-centre/resource-center?view=category&id=112> Accessed: 23 June 2013 9 Lydia Namono ‘Congestion at Mombasa port slows down trade in EAC Bloc’ Business Daily (Nairobi, 14 December 2012) 16-17 10 Ponciano Odongo ‘20km traffic jam hits Mombasa Road’ Business Daily (Nairobi, 24 May 2013) 9; Kurgat Marindany ‘Truckers protest bribery demands’ The Star (Nairobi, 24 May 2013) 7; 11 Willemien Viljoen ‘Non-tariff barriers affecting trade in the COMESA-EAC-SADC Tripartite Free Trade Agreement (2011) Stellenbosch, Trade Law Center (tralac) < ttp://www.tralac.org/2011/04/01/non-tariff-barriers-affecting-trade-inthe-comesa-eac-sadc-tripartite-free-trade-agreement> Accessed: 23 June 2013 12 Government of Kenya ‘Non Tariff Barriers for EAC—A Survey Report’ (Ministry of East African Community Nairobi, 2012) 5 7 Stakeholder involvement plays an integral part in the draft law prepared by the EAC, which establishes the framework for a legally enforceable mechanism for eliminating NTBs within the EAC. The Bill outlines a four-stage dispute resolution process. Of particular relevance is the first stage, of which private sector involvement—both individually and through business associations—is paramount The process begins with implementation of EAC Time-Bound Programme on Elimination of NTBs. If the NTBs remain unresolved, the matter is referred to the Council of Ministers, which shall issue a decision/directive with regard to the resolution of the NTB for immediate implementation. In the event that the Council decision is not implemented the matter shall be referred to arbitration by the Trade Remedies Committee for resolution. If this stage fails to resolve the NTB, the Trade Remedies Committee is required to refer the unresolved NTBs to the East African Court of Justice, whose decision shall be final and binding on parties in dispute. Such decision would be final and binding upon parties in dispute.13 Rwanda was the first country to call for the institution of legal mechanisms to accelerate the process of eliminating NTBs. 14 The draft law was submitted to the regional parliament—the East African Legislative Assembly—in November 2012, and is presently awaiting comments from member states. 4.3 The COMESA-EAC-SADC Online Mechanism15 The tripartite NTB Monitoring Mechanism--shared by SADC, COMESA, and the East African Community--is a web- based “post box” where the private sector can report complaints against NTBs to regional trade in Southern and Eastern Africa. It enhances transparency and easy follow-up of reported and identified NTBs and NTMs by businesses, government officers, and academic researchers. The online mechanism is already in operation, and has impressive functionality (text messages reporting violations may be also sent via mobile phone). The available statistics show that firms report trade-related administrative barriers most frequently as an impediment to regional trade, followed by import licensing.16 What remains to be seen is how much of an impact it will make over time within the EAC17 considering that the process depends on businesses and business associations using the system to report NTBs. 5.0 ‘Problematizing’ Stakeholder Forums: Limitations and Potentials This section reviews a number of key stakeholder forums, and, in drawing upon limited empirical research, highlights their inherent limitations and the considerable opportunity for further refinements before they can play their optimal role in terms of 13 Refer to Articles 12- 15, the Elimination of Non-Tariff Barriers in the EAC Bill 2012. 14 Muthoki Mumo, ‘EAC bloc acts to remove non-tariff barriers’ Daily Nation (Nairobi 18 June 2013) Smart Company 7 15 www.tradebarriers.com; Olivier Cadot, Mariem Malouche and Sebastian Saez Streamlining Non-Tariff Barriers-A toolkit for policymakers (World Bank, Washington DC, 2012) 113-5 < https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/6019> Accessed: 25 June 2013 16 As of 25 June 25, 2013 457 complaints had been registered; 349 complaints had been resolved; and 108 complaints were unresolved. 17 A meeting held on Monday 22 June 2013 between the author and a senior Kenyan government official in whose docket falls regional integration and trade-related issues revealed the mechanism is already in place within government, and that a working group was—on the same day—meeting to review the complaints received in relation to Kenyan-imposed NTBs. 8 overcoming NTBs. It is worthwhile to point out that the following insights derive from Kenya, rather than being representative of the EAC as a whole.18 5.1 Representation One key issue revolves around representation. This issue had several dimensions in the case of the transport and logistics sectors. On one hand, one respondent noted: I have observed that the Kenya Transporters Association (KTA) is very vocal, such that much of the representation from Kenya to the East African Business Council tends to revolve around clearing & forwarding issues.19 This rosy picture must nevertheless be held in juxtaposition to the observation that being vocal does not necessarily mean that all the players are represented in the same forum. Although truck drivers have their own welfare association, the Kenya Long Distance Truck Drivers Association, the truck owners also have their own association, the Kenya Transport Association (KTA): Although the KTA features most prominently, it is associated with only a few very-large transporter firms, mostly rich Arabs and Asians…. indigenous Africans are hardly represented in the board. So how can they speak for the entire industry..20 Similar issues regarding representation may be raised in relation to the manufacturing sector. Although the Kenya Association of Manufacturers (KAM) represents the country’s manufacturing sector within the NMCs and the East Africa Business Council (EABC), yet not all manufacturers are members of KAM. . It is submitted, here, that the key issue arising from both illustrations concern the necessity of ensuring that the stakeholder association in question meets the changing needs of their members as well as of the industry as a whole. This would be achieved through the use of strategies to enhance governance, management, and service delivery, and which ensure the association operates at standards that are equal or are higher than that of their members. 5.2. Communication A problem, related to that of representation, concern information-flow within the stakeholder forums, notably the NMCs. This concern has been acknowledged, notably in instances where trade disputes have been resolved at the top, but remain outstanding due to poor flow of information to implementing agencies. This has, to some extent, been addressed through the introduction of Trade Information Desk Officers, whose role was to provide timely and relevant information in the event of trade disputes arising at the border crossing.21 However, a slightly different scenario also presents itself within the business associations, where a respondent observed the following: 18 Interview with Kenyan government official, who is involved with regional integration issues, 15 May 2013 Interview with Kenyan government official, who is involved in regional integration issues, 25 June 2013 20 Interview with Mombasa-based transport and logistics professional, 23 June 2013 21 Joseph Mwamuyange ‘Inefficiency at Dar port swallows up $ 2.6b of GDP’ The East African (Nairobi, 25-31 May 20013) 9 19 9 In my experience representatives of some Kenyan business associations attend meetings yet they appear to lack detailed information about their members’ concerns… I even doubt they relay feedback to their members… I haven’t observed this with Rwanda and Uganda where the business community appears more cohesive, and dynamic22 5.3 Reforms A major concern arose when seeking to implement industry-wide reforms: It is difficult for the KTA to implement its code of ethics and instil order among its members when many of the transporters on the roads are part of the association. Perhaps government should compel everyone to become part of the KTA if they want to be licenced to carry out their work.23 Concerns were also raised about professionalism and corporate governance in general. This issue arose in relation to clearing and forwarding agents, where, government, through the Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) had earlier made it mandatory for all clearing and forwarding agents to become members of the Kenya International Freight & Warehouse Association (KIFWA): … previously, KIFWA only appeared to collect revenue without vetting or otherwise controlling its members…some of whom continue to be associated with unprofessionalism and unethical behaviour. No one knew where the money collected goes, except that it was wracked with internal squabbling. No wonder most members stopped taking it seriously…24 The key issue, here, therefore concerns avoiding manifestations of the “principalagent problem” 25 This entails the necessity of ensuring associations are run along principles of professionalism, through emphasis on policies and structures, whereby members can hold management to account, and where management are prevented from using their position for selfish agenda. It is worthwhile to note that government, now through the Kenya Maritime Authority—which is in charge of regulating transport and logistics—has developed a new curriculum for clearing and forwarding agents. As a respondent observed, ‘continued licencing will be tied to evidence of attendance of those courses. Over time, this may help. Previously KRA tried it, but it failed.’ 26 The key issues here, therefore, concern the necessity of sustaining institutional reforms in large settings which incorporate a large number of stakeholders, while minimising potential for capture, unprincipled deal-making, and rent-seeking. 5.3 Inclusivity 22 Interview with Kenyan government official, who is involved in regional integration issues, 25 June 2013 Interview with Nairobi-based transport and logistics professional, 3 July 2013 24 Interview with a journalist who is familiar with transport and logistics issues in the region, 5 July 2013 25 In other words, one person, the principal, hires an agent to perform tasks on his behalf but he cannot ensure that the agent performs them in precisely the way the principal would like. The decisions and the performance of the agent are impossible and or expensive to monitor and the incentives of the agent may differ from those of the principal. 26 Interview with Mombasa-based clearing and forwarding agent, 25 June 2013 23 10 There has been a notable omission of small businesses and informal cross-border traders within the respective stakeholder forums. This is despite the fact that East Africa’s economy is dominated by micro, small and medium size enterprise (MSMEs)27, of which micro-enterprises (engaging 1-10 persons) account for 87% of all enterprises in the region, and contribute to more than 60 per cent employment within the EAC28. This omission is also notable in the case of informal cross border trade, an activity which employs about 43% of Africans within Southern Africa, where women represent the lion’s share, around 75 % of the sector. Despite its importance in terms of contributing economic growth, job creation and food security, relatively empirical research has been done unlike the case of the formal trade.29 There are, nonetheless, several anecdotal accounts of the complexity of informal cross-border trade: At around 4 am, you would be amazed at the number of Kenyan women crossing the border into Tanzania to buy fish, fruits and various cereals. These ‘mama’s’ literally feed Nairobi and other major urban centres in Kenya30 The point was also made that such traders have suffered discrimination at the hands of the authorities due to their informal status and lack of proper documentation: You find that these small traders often don’t know where to turn. Even where they have formed welfare associations in their local markets, their elected chairpersons often do not know where or how to resolve their challenges31 One could also not rule out the fact that unscrupulous commercial traders would also masquerade as genuine small traders at border crossings in order to avoid taxes and duties: … an entire ‘industry’ has developed…brokers arrange to move entire lorryloads of grain across the borders using couriers on bicycles, who then repackage the grain on the other side, thereby avoiding the tax man’s demands32 The key point here is that there is need to clarify the circumstances under which cross-border traders could enjoy duty free access with simplified documents, a notion which is referred to as the Simplified Trade Regime (STR), as well as to understand the impact upon small-scale traders as well as to identify any challenges with the system so that they can be rectified early. The EAC Private Sector Development Strategy observes that the micro, small and medium size enterprises are a very significant part of the private sector in terms of number of enterprises and the number of jobs they create. 28 The 4th EAC Development Strategy, 2011/12—2015/16 29 Daniel Njiwa, 'Tackling informal cross-border trade in Southern Africa' <http://ictsd.org/i/competitiveness/158102/> Accessed: 16 July 2013 30 Interview with Kenyan government official, who is involved in regional integration issues, 25 June 2013 31 Interview with a trade policy officer in a membership organization dealing with regional agricultural trade and policy matters, 11July 2013 32 Interview with a trade policy officer in a membership organization dealing with regional agricultural trade and policy matters, 11July 2013 27 11 Conclusion What broader lessons can be gleaned from the preceding discussion? While there are inherent dangers in generalizing from the limited normative and empirical insights highlighted, nevertheless at least four key lessons may be gleaned. First, given the intractability of NTBs, one cannot afford to ignore the professed claims within the broader literature regarding stakeholder collaboration, namely that it can contribute to a rich understanding of and capacity to solve complex problems by harnessing the unique information, resources and capacities of diverse public and private actors, while also enhancing consensus among parties, by allowing diverse private and governmental actors to interact, deliberate and work together cooperatively. Following from this, however, is the recognition that what is lacking (and, accordingly, what is greatly needed), is rigorous, empirical scrutiny on how and under what conditions, stakeholder collaboration can enhance accountability horizontally within the JBCs, NMCs, the online reporting mechanism as well as any ad hoc stakeholder forums in order to subvert any self-interested behaviour, for instance rentseeking practices by corrupt leaders of stakeholder associations. Law, in other words, is viewed here as a potentially effective means of coercing individuals to act in their common interest, for instance through institutionalising industry codes of ethics, selfregulation of business associations, and compulsory certification of stakeholder associations. Given the limited scope of the empirical analysis, this conclusion should be termed as tentative, and further research on the range of appropriate policy mix is necessary. Third, there is also need to question whether and to what extent private sector stakeholders may use legal and regulatory intervention to foster accountability on the part of the respective governmental agencies. In a sense, governments possess three main regulatory tools: conventional regulation, instruments that affect incentives and the educational. The question for them has been to propose changes over time and the important thing is not to say that ‘a’ or ‘b’ or ‘c’ is best and always perfect, but it’s about getting the right mix of incentives and getting all three of them working in the same direction rather than at cross purposes. Finally, while the paper’s descriptive insights highlight significant limitations with stakeholder collaboration in one country, Kenya, specifically those pertaining to representation, communication, reforms and inclusivity, there is need to widen the inquiry to the entire EAC (including the landlocked countries), and perhaps even the tripartite Africa Free Trade Zone (AFTZ), which encompasses SADC, COMESA, in addition to the EAC. The emergent normative and empirical insights would go a long way towards adding to the limited store of knowledge that will assist both policy makers and legal scholars when thinking about, debating and reformulating the contribution of stakeholder collaboration towards solving multifaceted public problems.