Organizational Theory & Behavior Study Guide

advertisement

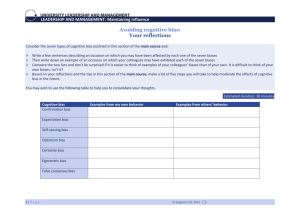

Organizational Theory & Behavior Study Guide Index Pgs 2-34 - Reframing Organizations Pgs 34-39 – Judgment and Managerial Decision Making Pgs 39-40 – Attribution Theory Pgs 40-42 - Promise and Peril of Pay-For-Performance Pgs 43- 45 – Learning to Fail Intelligently Pg 45 – Actionable Feedback Reframing Organizations – Bolman & Deal Chapter 1- Introduction Virtues & Drawbacks of Organizations: Prevalence of large, complex organizations is historically recent Much of society’s important work is done in or by organizations, but… They often produce poor service, defective or dangerous products and… Too often they exploit people and communities, and damage the environment Signs of Cluelessness: Management errors produces 100s of bankruptcies of public companies every year Most mergers fail, but companies keep on merging One study estimates 50 to 75% of American managers are incompetent Most change initiatives produce little change; some makes things worse Strategies to Improve Organizations: Better management Consultants Government policy and regulation What is a Frame? Mental map to read and negotiate a “territory” The better the map, the easier it is to know where you are and get around (a map of New York won’t help in San Francisco) Frame as window: enables you to see some things, but not others Frame as tool: effectiveness depends on choosing the right tool and knowing how to use it Structural Frame: Roots: sociology, management science Key concepts: goals, roles (division of labor), formal relationships Central focus: alignment of structure with goals and environment Metaphor for organization : Factory or machine Central Concepts: Rules, roles, goals, policies, technology, environment Image of Leadership: Social architecture Basic Leadership Challenge: Align structure to task technology, environment Human Resource Frame: Roots: personality and social psychology Key concepts: needs (motives), capacities (skills), feelings Central focus: fit between individual and organization Metaphor for organization: Family Central concepts: needs, skills, relationships Political Frame: Roots: political science Key concepts: interests, conflict, power, scarce resources Central focus: getting and using power, managing conflict to get things done Metaphor for organization: Jungle Central Concepts: Power, conflict, competition, organizational politics Image of Leadership: Advocacy Basic Leadership Challenge: Develop agenda and power base Symbolic Frame: Roots: social and cultural anthropology Key concepts: culture, myth, ritual, story, Central focus: building culture, staging organizational drama Metaphor for organization: Carnival, temple, theater Central Concepts: Culture, meaning, ritual, ceremony, stories, heroes Image of Leadership: Inspiration Basic Leadership Challenge: Create faith, beauty, meaning Expanding Managerial Thinking Traditional management thinking Artistic thinking See only one or two frames Holistic, multi-frame perspective Try to solve all problems with logic, structure Rich palette of options Seek certainty, control, avoid ambiguity, paradox Develop creativity, playfulness One right answer, one best way Principled flexibility Conclusions from Chapter 1: Narrow thinking leads to clueless managers Multiple frames improve understanding, promote versatility Multiple frames enabling reframing: viewing the same thing from multiple perspectives Chapter 2 - Simple Ideas, Complex Organizations (refer to Learning to Fail Intelligently article) Properties of Organizations: Organizations are complex Organizations are surprising Organizations are deceptive Organizations are ambiguous Sources of Ambiguity: Not sure what the problem is Not sure what’s going on Not sure (or can’t agree) on what we want Don’t have the resources we need Not sure who’s supposed to do what Not sure how to get what we want Not sure how to know if we succeed or fail Organizational Learning Peter Senge-We learn best from experience, but often don’t know consequences of our actions. Systems Maps Barry Oshry-Asymmetric relationships (top-middle-bottom-customer)—“Dance of blind reflex” Short-term Strategy Short-term gains Long-term costs Delay Argyris and Schon: -actions to promote learning actually inhibit it -defenses: avoid sensitive issues, tiptoe around taboos Coping with Ambiguity and Complexity: -what you see what you expect—and what you want -conserve or change? Advantages of relying on existing frames and routines Protect investment in learning them They make it easier to understand what’s happening and what to do about it …but we may misread the situation, take the wrong action, and fail to learn from our errors Change requires time and energy for learning new approaches but is necessary to developing new skills and capacities Common fallacies in Organizational Diagnosis Blame people Bad attitudes, abrasive personalities, neurotic tendencies, stupidity or incompetence Blame the bureaucracy Organization stifled by rules and red tape Thirst for power Organizations are jungles filled with predators and prey Conclusion Complexity, surprise, deception and ambiguity make organizations hard to understand and manage Narrow frames become rigid fallacies, blocking learning and effectiveness Better ideas and multiple perspectives enhance flexibility and effectiveness Chapter 3 – Getting Organized Structural Assumptions Achieve established goals and objectives Increase efficiency and performance via specialization and division of labor Appropriate forms of coordination and control Organizations work best when rationality prevails Structure must align with circumstances Problems arise from structural deficiencies Origins of the Structural Perspective Frederick Taylor – Scientific Management Efficiency, time and motion studies, etc. Max Weber – Bureaucracy Fixed division of labor Hierarchy of offices Performance rules Separate personal and official property and rights Personnel selected for technical qualifications Employment as primary occupation Structural Forms and Functions Blueprint for expectations and exchanges among internal and external players Design options are almost infinite Design needs to fit circumstances Basic Structural Tensions Differentiation: dividing work, division of labor Integration: coordinating efforts of different roles and units Criteria for differentiation: function, time, product, customer, place, process Sub-optimization: units focus on local concerns, lose sight of big picture Vertical Coordination Authority (the boss makes the decision) Rules and policies Planning and control systems Performance control (focus on results) vs. action planning (focus on process Lateral Coordination Meetings Task Forces Coordinating Roles Matrix Structures Networks Strengths and Weaknesses of Lateral Strategies McDonald’s and Harvard: A Structural Odd Couple McDonald’s: clearer goals, more centralized, tighter performance controls Harvard: diffuse goals, highly decentralized, high autonomy for professors Why have two successful organizations developed such different structures? Structural Imperatives Size and Age Core Process Environment Strategy and Goals Information Technology People: Nature of Workforce The case of Citibank Conclusion Structural frame – examine social context of work Differentiation and integration Structure depends on situation Simpler more stable simpler, more hierarchical and centralized structure Changing, turbulent environments more complex, flexible structure Chapter 4 – Organizing Groups and Teams Tasks and Linkages in Small Groups Structural Options Situational Variables Influencing Structure What are we trying to accomplish? What needs to be done? Who should do what? How should we make decisions? Who is in charge? How do we coordinate efforts? What do individuals care about most? What are special skill and talents? What is the relationship? How will we determine success? Basic Structural Configurations (Shown in the following figures) One Boss Dual Authority Simple Hierarchy Circle All Channel Figure 5-1: One Boss Figure 5- 2: Dual Authority Figure 5-3: Simple Hierarchy Figure 5-4: Circle Figure 5-5 All-Channel Teamwork and Interdependence Baseball Football Basketball Determinants of Successful Teamwork Determining an appropriate structural design Nature and degree of task interaction Geographic distribution of members Where is autonomy needed, given the team’s goals and objectives? Should structure be conglomerate, mechanistic, or organic? Task of management: fill out line-up card prepare game plan Influence flow Team Structure and Top Performance Six distinguishing characteristics of high-performing teams Shape purpose in light of demand or opportunity Specific, measurable goals Manageable size Right mix of expertise Common commitment Collectively accountable Saturn: The Story Behind the Story Quality, Consumer Satisfaction, Customer Loyalty Employees granted authority Assembly done by teams – Wisdom of Teams Group Accountability Conclusion Every group evolves a structure, but not always one that fits task and circumstances Hierarchy, top-down tend to work for simple, stable tasks When task or environment is more complex, structure needs to adapt Sports images provide a metaphor for structural options Vary the structure in response to change Few groups flawless members; the right structure can make optimal use of available resources Chapter 6 - People and Organizations Human Resource Assumptions Organizations exist to serve human needs People and organizations need each other When the fit between individual and system is poor, one or both suffer A good fit benefits both Human Needs The concept of “need” is controversial Economists: people’s willingness to trade dissimilar items disproves usefulness of concept Psychologists: need, or motive is a useful way to talk enduring preferences for some experiences compared to others Needs are a product of both nature and nurture Genes determine initial trajectory Experience and learning profoundly influence preferences Maslow’s Need Hierarchy Needs arrayed in a hierarchy Lower needs are “pre-potent” Higher needs become more important after lower are satisfied Maslow’s hierarchy: Self-actualization Esteem Belongingness, love Safety Physiological McGregor’s Theory X and Theory Y Theory X Workers are passive and lazy Prefer to be led Resist change Theory Y Management’s basis task is to ensure that workers meet their important needs while they work Either theory can be self-fulfilling prophesy Argyis: Personality and Organization Traditional management principles produce conflict between people and organizations Task specialization produces narrow, boring jobs that require few skills Directive leadership makes workers dependent and treats them like children Workers adapt to frustration: Withdraw – absenteeism or quitting Become passive, apathetic Resist top-down control through deception, featherbedding, or sabotage Climb the hierarchy Form groups (such as labor unions) Train children to believe work is unrewarding Human Capacity and the Changing Employment Contract Handy – Shamrock form Core group of managers Basic workforce – part-time or on shifts to increase organization’s flexibility Contractual fringe – temps, independent contractors Lean and mean (win through low costs): downsize, outsource, hire temps and contractors Invest in people (win with talent): build competent, well-trained work force Shift from production economy to information economy produces skill gap Conclusion Organizations need people and people need organizations, but the trick is to align their needs Dilemma: lean and mean vs. invest in people Chapter 7 – Improving Human Resource Management Build and Implement a Human Resource Philosophy Develop a public statement of the organization’s human resource philosophy Build systems and practices to implement philosophy Hire the Right People Know what you want and be selective Hire people who bring the right skills and attitudes Hire those who fit the mold Keep Employees Reward well and protect jobs Promote from within Powerful performance incentive Increases trust and loyalty Capitalizes on knowledge and skills Reduces errors Increases the likelihood to think longer-term Share the Wealth: give workers a stake in organization’s success Invest in Employees Invest in learning Create opportunities for development Empower Employees Provide Information and Support Make performance data available and teach workers how to use them Encourage workers to think like owners Everyone gets a piece of the action Foster Autonomy and Participation Redesign Work Build Self-Managing Teams Promote Egalitarianism Promote Diversity Develop explicit, consistent diversity philosophy, strategy Hold managers accountable Putting it all Together: TQM and NUMMI Total Quality Management High quality is cheaper than low quality People want to do good work Quality problems are cross-functional Top management is ultimately responsible for quality New United Motors Manufacturing, Inc. Getting There: Training and Organization Development Barriers to better human resource management Management reluctance Disrupts established patterns, relationships Lack of communication and interpersonal skills Training and OD to build capacity Group interventions: T-groups, large-group interventions (e.g., “Workout’ at GE) Survey feedback Conclusions High-involvement management strategies Strengthen employee-organization bond Pay well, share the benefits Job security Promote from within Training and development Empower and improve quality-of-work-life Participation, democracy, egalitarianism Job enrichment, teaming Promote diversity Chapter 8 – Interpersonal and Group Dynamics Interpersonal Dynamics Managers spend much of their time in relationships Three recurrent questions regularly haunt managers: What is really happening in this relationship? Why do other people behave as they do? What can I do about it? Argyris and Schön’s theories for action Espoused theory: how individuals describe, explain, or predict their own behavior Theory-in-use: the program that governs an individual’s actions Argyris and Schön’s theories for action Model I Theory in use Model I Assumptions Problem is caused by others Unilateral diagnosis Get person to change Model II Assumptions Emphasize common goals Communicate openly Combine advocacy with inquiry The Perils of Self-Protection Core values Action strategies (governing variables) Define and achieve Design and your own goals manage unilaterally Maximize winning, Own and control minimize losing what’s relevant to you Avoid negative feelings Protect yourself Be rational Unilaterally protect others Consequences for relationships You’re seen as defensive, inconsistent, selfish You generate defensiveness Consequences for learning Self-sealing You reinforce mistrust, conformity, avoiding risk Key issues become un-discussable Private testing of assumptions Single-loop learning Unconscious collusion to avoid learning Model I Assumptions Problems are caused by the other person Since they caused the problem, get them to change If they refuse or defend, that proves they caused the problem If they resist, intensify the pressure, protect them (to avoid discomfort), or reject them If you don’t succeed, it’s their fault; you’re not responsible Model II Assumptions Focus on common goals, mutual influence Communicate openly, test beliefs publicly Combine advocacy with inquiry Inquiry HIGH Advocacy LOW Assertive Integrative Passive Accommodating Emotional Intelligence Emotional Intelligence: awareness of self and others, able to deal with emotions and relationships (Salovey and Mayer) A Management Best-seller: Daniel Goleman’s Emotional Intelligence EI more important than IQ to managerial success Individuals with low EI and high IQ are dangerous in the workplace Management Styles Lewin, Lippitt and White: autocratic, democratic and laissez-faire leadership Fleishman and Harris: initiating structure vs. consideration of others Myers-Briggs Inventory Introversion vs. extraversion Sensing vs. intuition Thinking vs. feeling Judging vs. perceiving Big 5 Model” Extraversion (enjoying other people and seeking them out) Agreeableness (getting along with others) Conscientiousness (orderly, planful, hard-working) Neuroticism (difficulty controlling negative feelings) Openness to experience (preference for novelty and creativity) Groups and Teams in Organizations Informal Roles Informal role: an unwritten, often unspoken expectation about how a particular individual will behave in the group Individuals prefer different roles: some prefer to be active and in control, others prefer to stay in the background Individuals who can’t find a comfortable role may withdraw or become troublemakers Individuals may compete over the same role (for example, two people who both want to run things), hindering group effectiveness Informal Group Norms Informal norm: unwritten rule about what individuals have to do to be members in good standing Norms need to align with both the task and the preferences of group members Norms often develop unconsciously; groups often do better to discuss explicitly how they want to operate Interpersonal Conflict in Groups Develop skills Agree on basics Search for interests in common Experiment Doubt your infallibility Treat conflict as a group responsibility Leadership and Decision-Making in Groups How will we steer the group Leadership is essential, but may be shared and fluid Leaders who over-control or understructure produce frustration, ineffectiveness Summary Employees bring social and personal needs to the workplace Individuals’ social skills or competencies are a critical element Though often frustrating, groups can be both satisfying and efficient Chapter 9 – Power, Conflict, and Coalitions Assumptions of the Political Frame Organizations are coalitions Enduring differences among coalition members Allocation of scarce resources Conflict is central process and power most important resource Goals and decisions arise from bargaining, negotiation and jockeying for position Organizations as Coalitions Coalitions rather than pyramids Organizational goals are multiple and sometimes conflicting because they reflect bargaining involving multiple players with divergent interests Power and Decision-Making Gamson: Authorities and partisans Authorities make binding decisions Partisans are subject to authorities’ decisions; they will support or question authority depending on decisions affect their interests Sources of Power Position power Information and expertise Control and rewards Coercive power Alliances and networks Framing: control of meaning and symbols Personal power Distribution of Power: Over-bounded and Under-bounded Systems Over-bounded: strong, top-down control, conflict is tightly-regulated (e.g., Iraq under Saddam Hussein) Under-bounded: weak authority, chaotic decision-making, open conflict and power struggles (Iraq after collapse of old regime) Conflict in Organizations Conflict is natural and inevitable: organizations can have too much or too little Political frame focuses on strategy and tactics for dealing with conflict Forms of organizational conflict Hierarchical conflict Horizontal Cultural Moral Mazes: The Politics of Getting Ahead Getting ahead is a political process involving conflict for scarce resources Assessment of individual performance often depends on subjective judgments Does advancement depend on doing good work or doing what is politically correct? Organizations can’t eliminate politics, but they can influence the kind of politics they have Conclusion The political frame sees a very different world from the traditional view of organizations Traditional: organizations are hierarchies, run by legitimate authorities who set goals and manage performance Political view: organizations are coalitions whose goals are determined by bargaining among multiple contenders Politics can be nasty and brutish, but constructive politics is possible and necessary for organizations to be effective Chapter 10- The Manager as a Politician Skills of the Manager as a Politician Agenda Setting (knowing what you want and how you’ll try to get it) Vision or objective Strategy for achieving the vision Mapping the Political Terrain Determine the channels of informal communication Identify the major players Analyze possibilities for internal and external mobilization Anticipate the strategies that others are likely to employ Drawing the Political Map Frame the central issue – the key choice that people disagree about Identity the key players (those who are most likely to influence the outcome) Where does each player fall in terms of the key issue? How much power is each player likely to exert Example: Belgian bureaucracy Key issue: are automated records a good thing? Figure 10-1: The Political Map as Seen by the “Techies” – Strong Support and Weak Opposition for Change High TopManagement Techies Power Middle Managers Front-line Officials Low Pro-Change Opposed to Change Interests Figure 10-2: The Real Political Map: a Battle Ground With Strong Players on Both Sides High Top Management Techies Middle Middle Managers Managers Power Front-line Officials Low Pro-Change Opposed to Change Interests Skills of the Manager as a Politician Networking and Building Coalitions Identify relevant relationships Assess who might resist Develop relationships with potential opponents Persuade first, use more forceful methods only if necessary Bargaining and Negotiation Value Creating: look for joint gain, win-win solutions Value Claiming: try to maximize your own gains Value Creating: Getting to Yes (Fisher & Ury) Separate people from problem: “ deal with people as human beings, and the problem on its merits” Focus on interests, not positions Invent options for mutual gain Insist on objective criteria: standards of fairness for a good decision Value Claiming: The Strategy of Conflict (Schelling) Bargaining is a mixed-motive game (incentives to complete and collaborate)] Process of interdependent decisions Controlling other’s uncertainty gives power Emphasize threats, not sanctions Threats are only effective if credible Calculate the optimal level of threat: too much or too little can undermine your position Morality and Politics Ethical criteria in bargaining and organizational politics Mutuality – are all parties operating under the same understanding of the rules? Generality – does a specific action follow a principle of moral conduct applicable to all comparable situations? Openness – are we willing to make our decisions public? Caring – does this action show care for the legitimate interests of others? Conclusion Politics can be sordid and destructive, but can also be the vehicle for achieving noble purposes Managers need to develop the skills of constructive politicians: Fashion an agenda Map political terrain Networking and building coalitions Negotiating Chapter 11 – Organizations as Political Arenas and Political Agents Organizations as Arenas Arenas shape: Rules of the game Players Stakes Bottom-up Political Action Labor unions and civil rights movements Political Barriers to Control from the Top U.S. Department of Education scenario: initiatives often lost to political opposition despite new resources and top-down support Organizations as Political Agents Organizations exist in ecosystems Organizations depend on environment for resources support Organizations needs the skills of a politician: develop agenda, map environment, manage relationships with allies and competitors, negotiate Ecosystem “Organizational field” in which competitors and allies co-evolve Pfeffer and Salancik: The Eternal Control of Organizations Organizations are controlled more than they control their external environment Organizations are “other-directed” Struggle for autonomy and discretion in the face of constraint and external control Confront conflicting demands from multiple constituents Organizations’ understanding of environment is often distorted, imperfect Dilemma: alliances essential to gain influence, but reduce autonomy by increasing dependency and obligations Ecosystems Business Ecosystems Apple IBM “Wintel” General Motors and General Electric Public Policy Ecosystems Federal Aviation Administration Schools Business-government ecosystems Pharmaceutical companies, physicians and government Fedex lobbying clout Society as Ecosystem Business, public and government What is and should be the power relationship between organizations and society? Are organizations “instruments of market tyranny” or largely shaped by larger social and economic forces? Jihad vs. McWorld Conclusion Organizations are both arenas for internal politics and political agents with their own agendas, resources, and strategies Arenas house contests, shape ongoing interplay of interests and agendas Agents exist, compete and co-evolve in larger ecosystems (“organizational fields”) Chapter 12 – Organizational Culture and Symbols Core Assumptions of Symbolic Frame Most important – not what happens, but what it means Activity and meaning are loosely coupled People create symbols to resolve confusion, find direction, anchor hope and belief Events and processes more important for what is expressed than what is produced Culture provides basic organizational glue Organizations as Culture Organizations have cultures or are cultures? Definitions of culture: Schein: “pattern of shared basic assumptions that a groups has learned as it solved its problems…and that has worked well enough to be considered valid and taught to new members” “How we do things around here Culture is both product and process Embodies accumulated wisdom Must be continually renewed and recreated as newcomers learn old ways and eventually become teachers Manager who understand culture better equipped to understand and influence organizations Organizational Symbols Symbols reveal and communicate culture McDonald’s golden arches and legend of Ray Kroc Harvard’s myth, mystique and rituals Volvo France and Continental Airlines Myths: deeply-rooted narratives that explain, express and build cohesion Often rooted in origin legends (“how it all began”) Values: what an organization stands for and cares about Vision: image of future rooted in core ideology Heroes and Heroines Icons and living logos who embody and model core values Stories and Fairy Tales Good stories convey information, morals, values and myths vividly, memorably, convincingly Ritual Repetitive, routinized activities that give structure and meaning to daily life Men’s hut and initiation rituals Ceremony Grand, infrequent symbolic occasions Metaphor, humor, play “As if” role of symbols: indirect approach to issues that are too hard to approach head-on Metaphor: image to compress ambiguity and complexity into understandable, persuasive message Humor: way to illuminate and break frames Play: permits relaxing rules to explore alternatives, encourages experimentation and flexibility Geert Hofstede, Culture’s Consequences in Work-Related Values Culture: “collective programming of the mind that distinguishes one human group from another” Dimensions of national culture: Power distance: how much inequality between bosses and subordinates? Uncertainty avoidance: comfort with ambiguity Individualism: how much value on the individual vs. group? Masculinity-femininity: how much pressure on males for career-success and workplace dominance? Conclusion In contrast to traditional views emphasizing rationality and objectivity, the symbolic frame highlights the tribal aspect of contemporary organizations. Culture as basic organizational glue, the “way we do things around here” Symbols embody and express organizational values, ideology Chapter 13 – Organization as Theater Organizational Theater Theater plays to both internal and external audiences A convincing dramaturgical performance reassures external constituents, builds confidence, keeps critics at bay Institutional Theory “Institutionalized organizations” focus more on appearance than performance When goals are ambiguous and performance hard to measure (as in universities and many government agencies), organizations maintain stakeholder support by staging the right play, conforming to audience expectations of how the organization should operate DiMaggio and Powell, “The Iron Cage Revisited…” “Isomorphism” – process of becoming similar to other organizations in the same “organizational field” Coercive isomorphism – organizations become alike because law, regulation or stakeholders pressure them to do so Mimetic isomorphism – organizations become more alike by copying one another Normative isomorphism – organizations employing the same professionals become similar because the professionals have similar values and ideas Organizational Structure as Theater Structure as Stage design: an arrangements of lights, props and costumes Makes drama vivid and credible Reflects and expresses current values and myths Public schools reassure stakeholders if… The building and grounds look like a school Teachers are certified Curriculum mirrors society’s expectations Colleges judged by: Age, endowment, beauty of campus Faculty student ratio Faculty with degrees from elite institutions Organizational Process as Theater Activities (meetings, planning, performance appraisal, etc.) often fail to produce intended outcomes, yet persist because they help sustain organizational drama Scripts and stage markings: cue actors what to do and how to behave Opportunities for self-expression and forums for airing grievances Reassure audiences that organization is well-managed and important problems are being addressed Meetings as “Garbage cans” Attract an unpredictable mix of problems looking for solutions, solutions looking for problems, and participants seeking opportunities for self-expression Planning Plans are symbols Plans become games Plans become excuses for interaction Plans become advertisements Evaluations Often fail in intended goals of improving performance and identifying strengths and weaknesses Ceremony signals the organization is well-managed and cares about performance improvement Collective Bargaining Public face: intense, dramatic contest Private face: back-stage negotiation, collusion Power Exists in eye of beholder – you are powerful if others think you are May be attributed based on outcomes Conclusion Organizations judged by appearance The right drama: Provides a ceremonial stage Reassures stakeholders Maintains confidence and faith Drama serves powerful symbolic functions Engages actors in their performances Builds excitement, hope, sense of momentum Chapter 14 – Organizational Culture in Action The Eagle Group’s Sources of Success Why do some groups produce extraordinary results while others produce little or nothing? Play, spirit and culture are at the core of peak performance Success Principles How someone becomes a group member is important Diversity provides a team’s competitive advantage Examples, not command, holds a team together A specialized language fosters cohesion and commitment Stories carry history and values and reinforce group identity Humor and play reduce tension and encourage creativity Ritual and ceremony lift spirits and reinforce values Informal cultural players make contributions disproportionate to their formal roles Soul is the secret of success Conclusion Symbolic perspectives questions traditional views on team building Right structure and people are important, but not sufficient The essence of high performance is spirit Team building at its heart is a spiritual undertaking Chapter 15 – Integrating frames for Effective Practice Life as Managers Know It Myth: Managers are rational, spent time planning, deciding and controlling Organized, in control, unruffled Reality: Management life is hectic, frantic, constantly shifting Too busy to read or even think Rely on intuition and hunches for many of the most important decisions Hassled priests, modern muddlers, wheeler-dealers Across the Frames: Organizations as Multiple Realities Four Interpretations of Organizational Processes Doctor Fights to Quit Maine Island Organizations as Multiple Realities Process Structural Human Resource Political Strategic planning Decisionmaking Reorganizing Evaluating Approaching conflict Create strategic Meeting to Arena to air direction promote conflict participation Rational Open process to Chance to gain process to get build commitment or use power right answer Improve Balance needs and Reallocate structure/ tasks power, form environment fit new coalitions Allocate Help people grow Chance to rewards, control and develop exercise power performance Authorities Individuals resolve conflict confront conflict Keep organization headed in right direction Communication Transmit facts, information Goal setting Meetings Motivation Keep people involved and informed Exchange information, needs, feelings Formal Informal occasions to occasions to make decisions involve, share feelings Economic Growth, selfincentives actualization Matching Frames to Situations Choosing a Frame Commitment and motivation Technical quality Ambiguity and uncertainty Conflict and scarce resources Working from bottom up Bargaining, forcing, manipulating Let people make their interests known Influence or manipulate others Competitive occasions to score points Symbolic Ritual to reassure audiences Ritual to build values, bonding Image of accountability, responsiveness Occasion to play roles in organizational drama Develop shared values, meaning Develop symbols, shared values Tell stories Sacred occasions to celebrate, transform culture Coercion, Symbols, manipulation, celebrations seduction Choosing a Frame Question Are individual commitment and motivation essential? Is technical quality of decision important? Is there high level of ambiguity, uncertainty? Are conflict and scarce resource a significant factor? Are you working from the bottom up? If yes: Human resource, symbolic Structural If no: Structural, political Human resource, political, symbolic Political, symbolic Structural, human resource Political, symbolic Structural, human resource Political, symbolic Structural, human resource Effective Managers and Organizations Characteristics of Excellent/Visionary Companies Embrace paradox Clear core identity Effective Senior Managers Highly complex jobs requiring diverse skills Political dimension is critical Effective middle managers Structural and human resource skills help performance, but political skills help you get ahead Effective Organizations Frame Peters & Waterman Structural Collins & Porras Autonomy, Clock building, not entrepreneurship, bias for time telling; try a lot, action; simple form, lean keep what works staff Collins Human Resource Close to customer; productivity through people Home-grown management Confront brutal facts; best in world; economic engine; technology accelerators; “flywheel”, not doom loop “Level 5 leadership”; first who, then what Political ******** ******* ******* Symbolic Hands on, value-driven, BHAGs; cult-like Never lose faith; loose-tight; stick to the cultures; good enough deeply passionate; knitting never is; preserve the culture of discipline core, stimulate progress; more than profits Challenges in Managers’ Jobs Frame Kotter (1982) Lynn (1987) Luthans, Yodgetts, & Rosenkrantz (1988) Structural Keep on top of large, Attain intellectual grasp Communication complex set of of policy issues (paperwork, etc.); activities; set goals traditional management and policies under (planning, goal-setting, conditions of controlling) uncertainty Human resource Motivate, coordinate Use personality to best Human resource and control large, advantage management diverse group of (motivating, managing subordinates conflict, staffing, etc.) Political Allocate scarce Exploit opportunities to Networking (politics, resources; get achieve strategic gains interacting with support from bosses outsiders) and other constituents Symbolic Develop credible strategic premises; identify and focus on activities that give meaning to employees Manager’s Frame Preferences Research shows ability to use multiple frames is consistently associated with effectiveness. Effectiveness as manager – structural frame is key Effectiveness as leader – political and symbolic frames are central Conclusion Managers’ daily reality is messier, less rational, more conflict-filled than is often realized Choice of frame depends on circumstances Managers need multiple frames to survive Chapter 16 - Reframing in Action – Opportunities and Perils Cindy Marshall New manager with big challenge High risk dilemma: looking weak vs. acting impetuously Each frame suggests distinct possibilities Reframing as tool for generating options Scenarios: story-lines for generating options for action Each frame can be effective or not, depending on skill and insight of individual Structural Scenario Clarify goals Attend to relationships between structure and environment Design and implement structure to fit circumstances Focus on task, facts, logic, not personality or emotion Human Resource Scenario People are at the heart of organization Respond to their needs and goals, and they’ll be committed and loyal in return Align needs of individuals and organization, serving best interests of both Support and empower people Show concern, listen to their aspirations Communicate warmth and concern Empower through participation and openness Give people resources and autonomy they need to do their jobs Political Scenario Recognize political reality, deal with conflict Scarce resources produce conflict over who gets what Know the players (individuals and interest groups) and what they want Build ties to key players and group leaders Build a power base and use power carefully Overplaying your hand makes you weaker Create arenas for negotiation and compromise Look for and emphasize common interests to unify your group Rally troops against outside enemies Symbolic Scenario Most important part of leader’s job is inspiration Give people something to believe in People get excited about a special place with unique identity where their work is important Be passionate about making organization the best of its kind, communicate your passion Use dramatic, visible symbols to involve people, communicate the mission Be visible, energetic Create slogans, hold rallies and celebrations, give awards, manage by walking around Study and use organizational culture Use heroes, stories, traditions as a base for build cohesive, meaningful culture Articulate a persuasive, exciting vision The Power and Risks of Reframing Frames can be used as scenarios or scripts to generate options and guide action By choosing a new script, we can act in new ways and create new possibilities Choose the role and drama that works for you Each frame has distinctive advantages and risks Frame Risks Frame Risks Ignore non-rational elements: irrational neglect of human, political Structural and cultural elements Over-rely on authority and under-rely on alternative sources of power Human Resource Blinded by romantic view of human nature Too optimistic about trust and win-win in high-conflict/high-scarcity situations Political Symbolic Becomes cynical, self-fulfilling prophesy that intensifies conflict, misses opportunities for rationality and collaboration You may be seen as amoral, scheming, selfish Concepts are elusive Effectiveness heavily dependent on user’s art and skill Symbols may be employed as fluff, camouflage, manipulation Awkward use of symbols may produce embarrassment, ridicule Reframing for Newcomers and Outsiders Use of only one or two frames often leads to entrapment: inability to generate effective options in tough situations Risk is even higher for newcomers and outsiders (including members of groups that have historically been excluded) Newcomers and outsiders are less likely to get a second chance or the benefit of the doubt when they make mistakes Conclusion Mangers can use the frames as scenarios, or scripts, to generate alternative approaches to challenging circumstances. Reframing is a complex skill that takes time and persistence to develop Chapter 17 – Reframing Leadership Coping with leadership crisis: Queen Elizabeth II & Rudy Giuliani Queen Elizabeth In the face of Princess Diana’s death, the Queen stayed on vacation and issued short, tight-lipped statement She almost disappeared when constituents most wanted her to be present and reassuring Rudy Giuliani Went immediately to 9-11 scene and plunged in, at personal risk Took charge of disaster efforts Was continually visible: appeared on television, gave tours, etc. The Idea of Leadership Leadership often viewed as panacea: fix for whatever is wrong in organization or society Leadership not the same thing as power Leaders expected to persuade, inspire, not coerce or manipulate Leadership is distinct from authority Authority produces obedience because legitimated to make certain decisions Leadership vs. management Leaders think long-term, look outside as well as in, influence beyond their formal jurisdiction, have political skills, emphasize vision and renewal, The Context of Leadership Leaders make things happen, but things also make leaders happen What leaders can do always influenced by the stage on which they play their role Leadership is a relationship, a subtle process of mutual influence Leaders are non independent actors: they both shape and are shaped by circumstances and their constituents Leadership is distinct from position – you can lead from anywhere What Do We Know About Good Leadership? One Best Way Good leaders have certain characteristics in common Contingency Theories Good leadership depends on the situation One Best Way: Qualities of Highly Effective Leaders Vision and focus Image of future Standards for performance Clear direction Passion Deep personal, emotional commitment to the work and the people who do it Ability to inspire trust and build relationships Honesty is the trait followers say they admire most in a leader Blake & Mouton: The Managerial Grid Contingency Theories Leadership varies by situation, but there is no consensus on the nature of the key situational variables and how they influence leadership Hersey/Blanchard “Situational Leadership” model is popular, but research support is weak Hersey & Blanchard: Situational Leadership Gender and Leadership Do Men and Women Lead Differently? Karren Brady, Carly Fiorina, and Margaret Thatcher Do women have a “female advantage”? Research has found few consistent leadership differences between men and women Why the Glass Ceiling? Stereotypes linking leadership to maleness Women walk tightrope of conflicting expectations Discrimination Women pay a higher price Women may put higher premium on balancing work and family Women still do majority of housework and child-rearing in dual-career families Fast-track women less likely to marry, more likely to divorce than similar men Structural Leadership Effective Analyst, architect Leader Leadership process Analysis, design Ineffective Petty tyrant Management by detail and fiat Effective structural leaders… Do their homework Rethink relationship of strategy, structure, environment Focus on implementation Experiment, evaluate, adapt Human Resource Leadership Effective Catalyst, servant Leader Leadership process Support, empowerment Ineffective Weakling, pushover Abdication, indulgence Effective human resource leaders… Believe in people and communicate that belief Are visible and accessible Empower others Political Leadership Leader Leadership process Effective Advocate, negotiator Advocacy, coalition-building Ineffective Con artist, thug Manipulation, fraud Effective political leaders … Are clear about what they want and what they can get Assess distribution of power and interests Build linkages to key stakeholders Persuade first, negotiate second, and coerce only if necessary Symbolic Leadership Effective Ineffective Leader Prophet, poet Fanatic, fool Leadership process Inspiration, framing experience Mirage, smoke and mirrors Effective symbolic leaders… Lead by example Use symbols to capture attention Frame experience Communicate a vision Tell stories Study and use history Conclusion Leadership is widely accepted as a cure for all organizational ills, but it is also widely misunderstood. Leadership is relational and contextual, distinct from power and position Each of the frames highlights significant possibilities for leadership Managers need to combine multiple frames into a comprehensive approach to leadership Chapter 18 - Reframing Change: Training, Realigning, Negotiating, Grieving, and Moving on A Common Change Scenario: Thomas Lo at DDB Bank Profitable bank faced changing environment Thomas Lo recruited to improve service and innovate Lo introduced many changes, but six months later nothing was different Lo encountered lip service, passive resistance, but no overt conflict Familiar story: hopeful beginning, muddle middle, disappointing ending Change strategies that rely on only one or two frames usually fail Reframing Change Frame Barriers to Change Human resource Anxiety, uncertainty People feel incompetent, needy Structural Political Symbolic Essential Strategies Train to build new skills Participation & involvement; Psychological support Loss of clarity and stability; Communicating, realigning, confusion, chaos and renegotiating formal patterns and policies Disempowerment Create arenas for negotiating Conflict between winners & losers issues, forming new coalitions Loss of meaning and purpose; clinging to the past Transition rituals Mourn past , celebrate future Change and Training Change initiatives often fail because employees lack knowledge and skills People resist what they don’t understand, don’t know how to do, or don’t believe in Training, participation and support can increase understanding of why change is needed, as well as skills and confidence needed to implement Change and Realignment Structural change undermines existing patterns, creating ambiguity, confusion and resistance People don’t know how to get things done or who’s supposed to do what Change efforts need to anticipate structural issues, realign roles and relationships Change and Conflict Change creates winners and losers Winners support the change and fight for its implementation Losers resist, try to block change effort (and often succeed) Conflicts often are buried, where they smolder and become more unmanageable Successful change requires framing issues, building coalitions, and creating arenas where conflict can be surfaced and agreements negotiated Change and Loss Loss of a cherished symbol produces loss – akin to losing a job or a loved one Change produces conflicting impulses: replay the past vs. plunge into the future Cultures create transition rituals to ease loss Ritual and ceremony are essential to successful change: celebrate or mourn the past and envision the future Kotter: Stages of Effective Change Create sense of urgency Pull together guiding team with need skills, credibility and connections Create uplifting vision and strategy Communicate vision and strategy through words, deeds, symbols Remove obstacles, empower people to move Create visible progress: early wins Persist when things get tough Nurture and shape new culture to support new ways Reframing Kotter’s Change Model Kotter stage Structural Human resource Political Symbolic Involve, solicit input Sense of urgency Build guiding team Coordination strategy Team building Uplifting vision, strategy Communicate through words, deeds, symbols Implementation plan Build structures to Meetings to support change communicate, process get feedback Remove obstacles, empower Early wins Change old structures Keep going when going gets tough New culture to support new ways Keep people on plan Training, support, resources Plan for short-term victories Align structure to new culture Network with key players Build power base Stack team with key players Map political terrain Create arenas Build alliances Stack team with key players Do what it takes to get wins Tell compelling story Put CEO on team Create vision rooted in past Kickoff ceremonies Visible leadership Public hangings Celebrate early progress Revival meetings Create “culture” Stack team team with key Broad players involvement in creating new culture Mourn past Celebrate heroes Share stories Team Zebra: The Rest of the Story Top-down, Bottom-up Structural Design Learning and Training Areas for Venting Conflict Occasions for Letting Go and Celebrating Core values Encouraging rituals Anchoring vision Inventing ceremonies to keep spirit high Conclusion Major organizational change inevitably generates four categories of issues Affects individuals’ ability to feel effective They need training, participation, support Change disrupts existing patterns Structure needs to be realigned Change creates conflict Need arenas to negotiate conflict, reach agreements Change creates loss of meaning for recipients Need transition rituals to mourn past and celebrate future Chapter 19 – Reframing Ethics and Spirit Soul and Spirit in Organizations Organizational soul: bedrock sense of identity, clarity about core ideology and values Core ideology emphasizing “more than profits” key to highly successful firms (Collins and Porras, 1994) Enron Rapid shift from pipelines to deal-making produced enormous growth -for a while In the process, Enron lost a sense of core identity and values (“lots of smart people, but no wise people”) Merck Core purpose: not profit but “preserve and improve human life” Developed and gave away river blindness drug Conclusion Organizational ethics ultimately need to be rooted in soul Modern organizations suffer a crisis of meaning and moral authority Leaders need to hold and model values like excellence, caring, justice, faith Conclusion: Reframing, like management and leadership, is much more art than science. Judgment in Managerial Decision Making--Bazerman The book’s main objective: To improve the reader’s judgment by attempting to unfreeze the reader’s present decision-making processes by demonstrating how your judgment systematically deviates from rationality. It also gives tools that allow you to change your decision-making processes and the methods that will allow the reader to refreeze thinking to ensure that it will last. Chapter 2 – Specific biases that affect the judgment of virtually all managers. They are caused by three heuristics. Bias 1—Ease of Recall (based on vividness and recency) o An availability bias Bias 2—Retrievability (based on memory structures) o An availability bias o Organizational mode affects information search behavior Bias 3—Presumed Associations o An availability bias o Frequently occurs when assessing the likelihood of two events occurring together The availability heuristic helps us often make accurate, efficient judgments in estimating the likelihood of events. Misusing it can lead to the three previously mentioned errors in managerial judgment Bias 4—Insensitivity to Base Rates o This bias often occurs when individuals cognitively ask the wrong question o Representativeness heuristic Bias 5—Insensitivity to Sample Size o Sample size is seldom part of our intuition o Representativeness heuristic Bias 6—Misconceptions of Chance o Gambler’s fallacy—the expectation that probabilities will even out o The “hot hand” in sports o We expect a sequence of random events to “appear” random o Representativeness heuristic Bias 7—Regression to the Mean o Many effects regress to the mean—counterintuitive in many cases o Representativeness heuristic Bias 8—The Conjunction Fallacy o Simple statistics demonstrate that a conjunction cannot be more probable than any one of its descriptors o Can be triggered by a greater availability of the conjunction than its descriptors. o This biasing effect tends to be greater in groups than individuals o Representativeness heuristic These five biases are examples of the representativeness heuristic—the likelihood of a specific occurrence is related to the likelihood of a group of occurrences which that specific occurrence represents. It tends to be overused in decision-making. Bias 9—Insufficient Anchor Adjustment o Individuals make estimates for values based upon an initial value (derived from past events, random assignment, or whatever information is available) and typically make insufficient adjustments from that anchor when establishing a final value. o Anchoring and adjustment heuristic Bias 10—Conjunctive and Disjunctive Events Bias o Individuals exhibit a bias toward overestimating the probability of conjunctive events and underestimating the probably of disjunctive events. o Anchoring and adjustment heuristic Bias 11—Overconfidence o Individuals tend to be overconfident of the infallibility of their judgments when answering moderately to extremely difficult questions. o Anchoring and adjustment heuristic Other biases: Bias 12—The Confirmation Trap o Individuals tend to seek confirmatory information for what they think is true and fail to search for disconfirmatory evidence Bias 13—Hindsight and the Curse of Knowledge o After finding out whether or not an event occurred, individuals tend to overestimate the degree to which they would have predicted the correct outcome. Furthermore, individuals fail to ignore information they possess that others do not when predicting others’ behavior. Chapter 3 – Examining the psychological factors that explain how managers deviate from “rationality” in responding to uncertainty. Decision makers are grasping for certainty in a certain world People tend to cope with uncertainty by ignoring it The need to do way with uncertainty leads people to take too much credit for successes and too much blame for failures Managers can make better decisions by accepting that uncertainty exists and by learning to think systematically in risky environments—risk is not bad; it is simple unpredictable. Two key concepts of a normative theory of preferences under risky conditions: o Probability – the likelihood that any particular outcome will occur Probability can be very complex, both mathematically and psychologically o Expected value – the weighting of all potential outcomes associated with an alternative by their probabilities and summing them People do not always follow the expected-value rule Risk considerations Risk neutral—certainty equivalent for an uncertain event that is equal to the expected value of the uncertain payoff is risk neutral (same as using expected-value rule) Risk adverse—certainty equivalent for an uncertain event that is less than the expected value of that uncertain payoff Risk seeking—certainty equivalent for an uncertain event that is more than the expected value of that uncertain payoff Utility = degree of pleasure or net benefit Expected-utility theory—individuals identify outcomes in terms of their overall wealth and the additional wealth they would gain from each alternative outcome Framing Information key concepts: o Individuals treat risks concerning perceived gains differently from risks concerning perceived losses Prospect theory People evaluate rewards and losses relative to a neutral reference point People think about potential outcomes as gains or losses relative to this fixed, neutral reference point People form their choices based on the resulting change in asset position as assessed by an S-shaped value function. The way the problem is “framed,” or presented, can dramatically change the perceived neutral point of the question Our response to loss is more extreme than our response to gain. We tend to overweight the probability of low-probability events and underweight the probability of moderate and high-probability events Framing of Risky Decisions o We would be wise to follow the expected value rule when making decisions o Deviations from this rule in the real world should probably be reserved for critically important decisions, after careful consideration of the problem from multiple frames Anchors matter therefore: Identify your reference point when making a risky decision Ask if other reference points exist If yes—think about the decision from multiple frames and examine any contradictions that emerge Pseudo-certainty o People value the creation of certainty over the equally valued shift in the level of uncertainty o Certainty effect—a reduction of the probability of an outcome has more importance when the outcome was initially certain than when it was merely probable. Other key terms: o Acquisition utility—the value you place on a commodity o Transactional utility—the quality of the deal that you receive, evaluated in reference to “what the item should cost.” o Endowment effect—the value a person places on a commodity is related to its intrinsic worth and the value placed on his or her attachment to the item. In other words—we tend to over value what we own o Chapter 4 – Overview of motivated biases Two selves: Want vs. Should o Want self—more transient, visceral, adaptive to natural environment, more based on emotional criteria—tends to dominate when only one option is assessed at a time o Should self—more long term focused, more conservative and risk adverse—tends to dominate when multiple options are considered. o If there is conflict between the two, it may be an indication that you need to think more carefully about the information provided by each of the two selves. Ignoring the want self may lead to rebellion and sabotage. It is important to come to a negotiated agreement through favoring the should approach but getting input or voice to the want self.(decision-theoretic approach) o Positive illusions—we tend to view ourselves, world, and future more positively than what it is in reality or objectively likely. Four most important positive illusions: Unrealistically positive views of the self—individuals tend to perceive themselves as being better than others on a variety of desirable attributes Unrealistic optimism—a judgmental bias that leads people to believe that their futures will be better and brighter than those of other people. The illusion of control—people believe that they can control uncontrollable events. Self-serving attributions—people interpret the causes of events in a biased manner. Success is perceived as the result of internal reasons. Failure is attributed to external reasons The same positive illusions also occur at the group and society level o Positive illusions may be adaptive and helpful in some instances; they tend to have a negative impact on learning and the quality of decision making, personnel decisions, and responses to organizational crises. They can also contribute to conflict and discontent. o Egocentrism—perceptions and expectations tend to be biased in a selfserving manner o We are highly motivated to avoid regret in decision making Chapter 5 – The research evidence and psychological explanations for why managers may make subsequent non-optimal decisions in order to justify their previous commitment to a particular course of action. (Escalation) Why does escalation occur? o Perceptual biases o Judgmental biases o Impression management o Competitive irrationality Implication: Managers should take an experimental approach to management. Make and implement a decision but be open to dropping your commitment and shift to a different course of action if the first plan doesn’t work out. Chapter 6 – The concept of fairness and our inconsistencies in our assessments of fairness. Judgments of fairness are made throughout organizational life. Fairness and comparison help us make interpret our world. Judgments of fairness are based on more than objective reality. *Feel free to refer to Chapter 10 for a summary on how to improve decision-making. Fiske: Attribution theory - Biases, errors, and criticisms: Fundamental Attributional Error—attributes another person’s behavior to his or her own dispositional qualities, rather than to situational factors. o Qualifications of FAE: Our methods for detecting the actual causes of behavior are quite poor. Subjects in experiments may have been answering a different question than the researcher believed was being asked. People over-attribute another’s behavior to situational factors— thus underestimating dispositional factors. The Actor-Observer Effect—to see your own behavior as quite variable, but others’ behavior as quite cross-situationally stable. o Qualifications of AOE: The AOE is weakened when positive or negative, as opposed to neutral, outcomes are involved. There are circumstances when the actor might make more dispositional attributions for his or her own behavior than an observer would. The category “situational attributions” is ambiguous, and people may use it when they are not sure what caused behavior. The AOE can be reversed with empathy set behaviors (pretending to observe one’s self from the perspective of another person. Active observers are usually more likely to attribute an actor’s behavior dispositionally than passive observers if the behavior is not neutral or if they empathize with the actor Underutilization of Consensus Information—failing to sufficiently assess the accuracy of our causal perceptions by comparing them with those of others. o Qualifications of UUCI: Consensus had the weakest effect on attributions Whereas consensus information may change one’s perceptions of how common an experience is, it does not change the experience itself. Consensus information may not seem as trustworthy as other kinds of experience. Consensus information is often overruled by what might be termed self-based consensus. When a person has strong prior beliefs about what is normative, he or she is likely to ignore discrepant opinions offered by others. Self-Based (False) Consensus Effect—to see one’s own behavior as typical, to assume that under the same conditions, others would have reacted the same way as oneself. o Explanations: We seek out people similar to us We must resolve ambiguous details in our minds We have a need to see our own beliefs and behaviors as good, appropriate, and typical while attributing them to others defensively to preserve our self-esteem. Defensive Attributions—Observers attribute more responsibility for an accident that produces severe, rather than mild consequences. o Explanations: If you find yourself in similar circumstances as the perpetrator, you may deny similarity to the perpetrator. If personal similarity is high, you will probably attribute the accident to chance or bad luck to minimize implications for similar future outcomes befalling you. Self-Serving Attributional Biases—take credit for successes and deny responsibility for failure. o Key points: There is far more evidence that people take credit for success than they deny responsibility for failure. Sometimes the opposite is true It seems that cognitive and motivational factors contribute to selfserving biases. Self-serving biases may extend beyond explanations for one’s own behavior to include the people and institutions with which one is allied. Self-Centered Bias—taking more than one’s share of responsibility for a jointly produced outcome. o Key points: There are cognitive and motivational explanations for this bias Not all apply in all instances One tends to be able to notice and recall instances of one’s own contributions more easily than those of another person. What do attributional biases say about the social perceiver? o The social perceiver adopts the self as a central point of reference—things are generally seen in ways that are advantageous to the ego. o Biases produce an underlying conservatism: a willingness to form stable attributions, especially about others and an unwillingness to amend or change one’s beliefs, whether about others or the self, in the face of discrepant evidence. Promise and Peril in Pay for Performance—Beer & Cannon Focus of the article is on the experience of managers in one company in implementing pay for performance and how they made sense of and made decisions about their pay-forperformance initiatives. The article deals with how an organization’s particular culture might affect its management’s ability to effectively implement a particular pay-forperformance system. The example used in the article was Hewlett Packard. Key points: o Pay for performance seemed to motivate behavior desired by management as initial. o Managers tend to be unrealistically optimistic about what can be accomplished by a management intervention. o Design and maintenance of effective pay-for-performance programs is complicated—especially in a rapidly changing business environment. o There were significant barriers to linking pay to performance. o Ineffective design or maintenance can cause significant problems such as bitter feelings and damage to important relationships. o Implementation costs and risks of pay-for-performance systems appear to be higher in high-commitment cultures where trust and employee commitment is perceived by managers to be crucial to long-term success. An alternative conclusion is that monetary incentives in a fast-changing environment may undermine the capacity of a firm to build trust and commitment unless the process of introduction incorporates an honest discussion of mutual expectations. Baron’s commentary key points: o Pay for performance itself is not dangerous per se, but rather systems that excessively emphasize financial rewards for performance. o Instead of pay for performance, we need to think more broadly about rewards for performance. o PFP plans can attain superior results when their framing, communication, and implementation don’t batter employees over the head with financial attributions for their behavior. Dailey’s commentary key points: o It is wrong to connect Carly Fiorina (HP CEO) with the outcomes of these experiments. o Fundamental principles of good change management seem to be missing in all of these experiments. o Change is complex o The risk/return issues of various organizational change initiatives would be a very productive topic for the authors to focus more attention on. o PFP requires pay systems and mangers to encourage certain selected behaviors and reward differentially the resulting outcomes. o HP has a long reputation for “start-stop” practices on many things. o Words are important. Gerhart’s commentary key points: o More established companies may have a harder time implementing PFP than those that implemented it from the beginning. o Does not believe that any evidence from employment settings that PFP necessarily harms intrinsic motivation or creativity. The design of the program may impact its effect on teamwork. o It is important to recognize that PFP can have beneficial effects via attraction-selection-attrition. o More weight is given to the competence of “local management.” Heneman’s commentary key points: o Why the plan failed Lack of knowledge and skill regarding PFP plans among site managers. They were unable to anticipate problems Attempts to facilitate implementation with the use of other mechanisms that typically accompany the PFP plans, particularly formal communication and training programs, were missing. HR department or function was missing. Kochan’s commentary key points: o There is no PFP plan that management is likely to dream up and implement unilaterally that will work. o There is no substitute for employee voice. o The challenge lies in making implicit negotiations explicit and real Ledford’s commentary key points: o Why HP abandoned the new pay programs: Definition of PFP Success criteria Company-specific issues Locke’s commentary key points: o Why four of the five HP plans were not well-designed: The use of team-based pay when the proper bonus unit perhaps should have been larger Combining performance bonuses with skill-based pay Changing the standards Non-control over performance The use of competition to determine bonuses Lack of sufficient employee knowledge Bonuses too small o Incentive plans need to be designed very carefully o Is not convinced that incentive plans may be unsuitable within a highcommitment culture o Disagrees with the notion that organizational change programs fail because they are pushed from the top. Rather, they fail because the programs are not pushed hard enough. Beer and Cannon’s response to commentaries: o Disagree with the implication that if managers had just been a bit smarter and more experienced in designing and implementing PFP, these programs could have been avoided. o A legitimate goal of PFP might simply be fair pay Failing to Learn and Learning to Fail Intelligently—Cannon & Edmondson Three core aims: 1. To provide insights about what makes organizational learning from failure difficult, paying particular attention to what we see as a lack of understanding of the essential processes involved in learning from failure in a complex organizational system such as a corporation, hospital, university, or government agency. 2. To develop a model of three key processes through which organizations can learn how to learn from failure. Learning from organizational failure is feasible—it involves skillful management of the interrelated processes of identifying failure, analyzing failure, and deliberate experimentation. 3. To argue that most managers underestimate the power of both technical and social barriers to organizational learning from failure, leading to overly simplistic criticism of organizations and managers for not exploiting learning opportunities. Organizational failure = deviation from expected and desired results which include both avoidable errors and the unavoidable negative outcomes of experiments and risk taking. It also includes large and small failures Key points: Most organizations do not learn from failure due to their lack of attention to small, everyday organizational failures. Identifying small failures (early warning signs) and addressing them when they occur may be the key to avoiding catastrophic failure in the future. Learning from failure is a hallmark of innovative companies but most organizations do a poor job of putting it into practice. Barriers of organizational learning: o Barriers embedded in technical systems—lack of scientific know-how to be able to draw inferences systematically, the presence of complex systems or technologies, task design flaws or errors, etc. o Barriers embedded in social systems—strong psychological reactions to failure, self-esteem and ego protection attempts, positive illusions, attributions, organizational cultures, social factors. These can also discourage reporting failure as well. Learning from failure is just as much a process as an outcome. The three processes are: o Identifying failure o Analyzing failure o Deliberate experimentation Proactive effort to surface available data on failures for use in ways that promote learning is required by managers. Formal processes or forums for discussing, analyzing, and applying the lessons of failure elsewhere in the organization are needed to ensure that effective analysis and learning from failure occurs. Skills for managing a group process of analyzing a failure with a spirit of inquiry and sufficient understanding of the scientific method is an essential input to learning from failure as an organization. When analyzing failure we are more prone to attribute too much blame to other people and forces beyond their control. This reduces the ability to learn from the experience The value of learning from analyzing and discussing simple mistakes is often overlooked. Recommendations on technical barriers: o Build information systems to capture and organize data, enabling detection of anomalies, and ensure availability of systems analysis expertise. o Structure After-Action-Reviews or other formal sessions that follow specific guidelines for effective analysis of failures, and ensure availability of data analysis expertise. o Identify key individuals for training in experimental design; use as internal consultants to advise pilot projects and other line (operational) experiments. Recommendations on social barriers: o Reinforce psychological safety through organizational policies such as blameless reporting systems, through training first line mangers in coaching skills, and by publicizing failures as a means for learning. o Ensure availability of experts in group dialogue and collaborative learning, and invest in development of competencies of other employees in these skills. o Pick key areas of operations in which to conduct an experiment, and publicize results, positive and negative, widely within the company. Set target failure rate for experiments in service of innovation and make sure reward systems do not contradict this goal. Reframing Failure to a learning-oriented frame: o Reframe expectations about failure as a natural byproduct of a healthy process of experimentation and learning o Reframe beliefs about effective performance involving avoiding failures to involving learning from intelligent failure and communicating the lessons broadly in the organization. o Reframe self-protective psychological and interpersonal response to failure to curiosity, humor, and a belief that being the first to capture learning creates personal and organizational advantage. o Reframe leadership from day to day management operation to recognizing the need for spare organizational capacity to learn, grow, and adapt for the future. o Reframe managerial focus of controlling costs to promoting investment in future success. Five Characteristics of Intelligent Failures: 1. They result from thoughtfully planned actions. 2. They have uncertain outcomes. 3. They are modest in scale. 4. They are executed and responded to with alacrity. 5. They take place in domains that are familiar enough to permit effective learning. Reframing failure to be associated with risk and improvement is a critical first step on the learning journey. Actionable Feedback - Unlocking the Power of Learning Key Ideas: Actionable feedback is feedback that produces learning and tangible, appropriate results, such as increasing effectiveness and improving performance on the job. Candid, insightful feedback is essential to development and learning (at times, it can have a negative impact on performance) Cognitive and emotional dynamics can make it difficult to give and receive feedback—therefore hindering learning and development. Attributional biases can affect either party and lead them to form conflicting views. Self-serving biases and actor-observer biases are particularly relevant here in explaining why conflicting views emerge. Delivery of negative feedback can be seen as a personal attack and threaten one’s ego. Feeling this way can hinder learning. Flawed feedback: o Attacks the person rather than the person’s behavior o Vague or abstract assertions o Without illustrations o Ill-defined range of application o Unclear impact and implications for action Cognitive and emotional dynamics impacting feedback givers: o Inference-making limitations o Attributional biases o Overconfidence o Third-party perspective differences o Strong emotions can impact ratings and feedback formulation and delivery Taking a third-party perspective and understanding the ladder of inference can be extremely helpful in improving feedback. Engaging in self-questioning and 360degree feedback is also helpful o The ladder of inference steps: Select data Paraphrase the data Name what’s happening Explain/evaluate what’s happening Decide what to do