Chu Hwang

advertisement

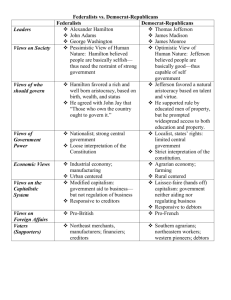

Chu Hwang Professor Milkis GFAP 331: American Presidency 7 March 2002 At the Constitutional Convention in 1787, the Founders shaped an executive branch, represented by the president, who would work and balance power with the legislative and judicial branches in the newly-created system of republican government. They envisioned an independent president who would moderate the popular will and elevate the public view—a nonpartisan leader. The Founders, however, did not predict the rise of political parties, which greatly changed the role of the president in their constitutional system of representation. Because of the development of parties, the early presidents had to reconstruct the presidency to manage or incorporate the new institution into the constitutional government. George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Andrew Jackson all faced the challenge of dealing with the rise of parties, which is not accounted for in the Constitution and each president confronted the problem differently: George Washington attempted to maintain the nonpartisanship envisioned by the Constitution, Thomas Jefferson became a party leader as president reluctantly, and Andrew Jackson reveled in integrating the two-party system in the White House. With the passing of time, the representational role of the president evolved from the Founders’ original conception of the presidency. Unlike the expectation for modern-day presidents to be overtly partisan, the Founders expected the head of the executive branch to be a disinterested republican gentleman who would unite the different factions of the country. As James Ceaser describes, the Founders created a president whom they hoped would embody “‘nonpartisan’ statesmanship. Under this form of leadership, the elevation of individuals to office should be the result of their having achieved a widespread reputation based on distinguished service to the state. The winner in such a process, no matter what his margin of victory, can in a sense legitimately assert the claim to be president of all the people, since his election would not divide the populace into strongly antagonistic parts.”1 James Wilson, who attended the Constitutional Convention as a Pennsylvanian delegate, expressed Founders’ ideal of the role of the president at the Pennsylvania ratifying convention: “[The president] will be…THE MAN OF THE PEOPLE; being elected by the different parts of the United States, he will consider himself as not particularly interested for any one of them, but will watch over the whole with paternal care affection.”2 The Founders hoped that the role of the president would be to look out for the public good while balancing the powers of government. The Founders’ ideal president was embodied in the presidency of George Washington, who made an effort to maintain disinterested and nonpartisan. To uphold the vision of the Founders, Washington asked Congress, in his first inaugural address, to look beyond parties and interests in considering national policy: “I behold the surest pledges that as on one side no local prejudices or attachments, no separate views nor party animosities, will misdirect the comprehensive and equal eye which ought to watch over this great assemblage of communities and interests, so, on another, that the foundation of our national policy will be laid in the pure 1 James Ceaser, Presidential Selection: Theory and Development (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1979), 58. 2 Richard J. Ellis, Founding of the American Presidency (New York: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 1999), 149. and immutable principles of private morality.”3 Washington did not look fondly upon political parties and as the Federalist party, led by Alexander Hamilton, and Democratic-Republican party, headed by Thomas Jefferson began to emerge in his administration, he did not support either of them. The Neutrality Proclamation of 1793, which established that the United States would not give aid or weapons to the warring countries of Britain and France, was a sign of Washington’s attempt to placate both parties. Following the advice of Hamilton, Washington announced the Neutrality Proclamation; however, he attempted to appease Jefferson by receiving a representative from the new Republic of France4, an action that Hamilton had rejected.5 The political divide between Hamilton and Jefferson had been caused by their different views on the role of the government, especially the executive. Jefferson’s presidency allowed him to redefine the role of the executive, particularly on how to integrate newly formed political parties into the system of government. The presidency of Jefferson was marked by an ambivalent increase in partisanship and a greater incorporation of parties in government. Instead of following Washington’s example of disinterestedness and serving as an umpire to diverse factions and parties, Jefferson “assumed the mantle of party leader in an effort to direct the separate branches of American government.”6 Jefferson’s first inaugural address hinted at his reinterpretation of the role of the president as a party leader; in his address, he proposed clearly Democratic-Republican policies such as “the support of the State governments in all their rights” and “encouragement of agriculture, and of commerce as its handmaid.”7 Despite his establishment of a party platform in his inaugural address, Jefferson still called for unity and nonpartisanship: “Every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle. We have called by different names brethren of the same principle. We are all republicans, we are all federalists.”8 Even though Jefferson was the first president acting as party leader, he did not intend for presidents in the future to do so; he hoped that as party leader, he would be able to destroy the party system by uniting the country under one party. Ceaser expresses the ambivalence of 3 Michael Nelson, The Evolving Presidency (Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly, 1999), 33. By receiving the representative from France, Jefferson actually acknowledged the president’s dominant role in foreign affairs, for which Hamilton and the Federalists argued. 5 Sidney Milkis and Michael Nelson, The American Presidency: Origins and Development 1776-1998 (Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly, 1999), 77-8. 6 Ibid., 99. 7 Nelson, 48-9. 8 Ibid., 47. 4