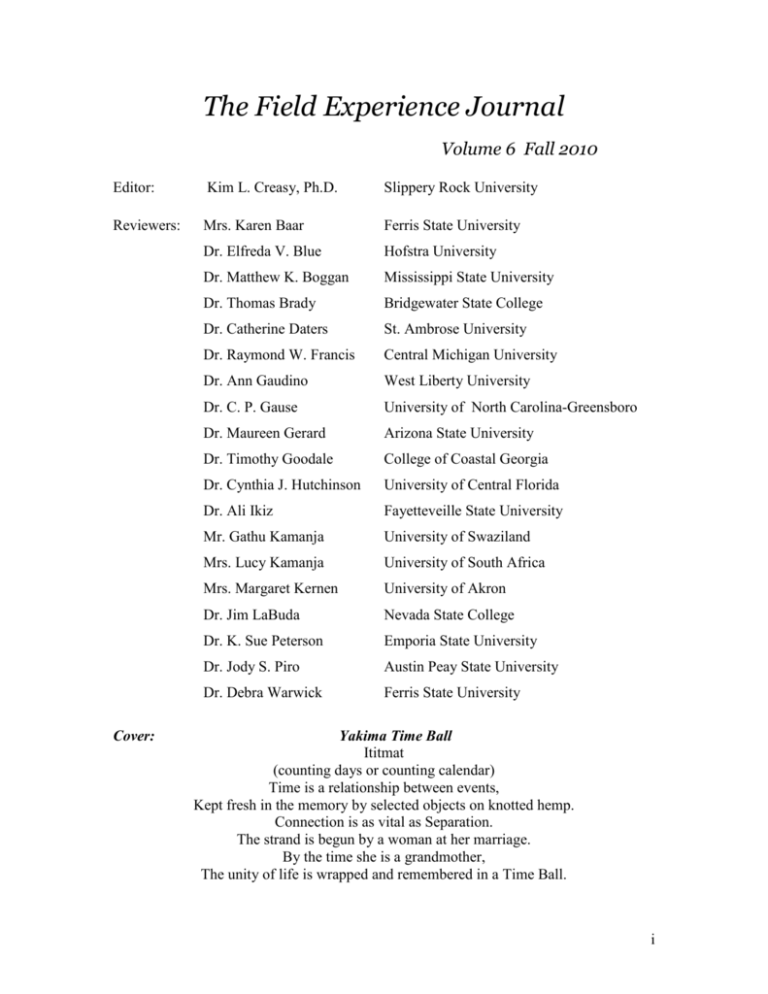

The Field Experience Journal - University of Northern Colorado

advertisement