Document

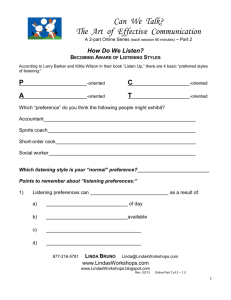

advertisement

Much has been written about leadership skills and the training of department chairs. A quick perusal of The Department Chair shows topics related to marketing your department, performance appraisals, reward systems, conflict management, team-building, recruitment, and leading workshops - all important leadership issues. Books to help chairs develop as leaders focus primarily on theoretical issues. When communication is covered, it is within the realm of written communication, leading department meetings, motivational skills, and meeting deadlines. Missing from much of the literature is the communication skill of listening. This is not surprising considering that listening is the skill most overlooked in management books as well as college curricula. Listening is one of the most critical skills needed for effective leadership. Unfortunately, it is a time-consuming task. However, because faculty need their chairperson to take time to understand and appreciate them, chairs must invest in improving listening skills. This article posits that listening, while the forgotten stepchild of communication, is the most important skill a department chair can develop. Listening and Leadership Research shows that between 42%-60% of our time is spent listening, depending on one's vocation. Active listening requires not only time, but also complete concentration and focus on the one who is talking. Active listeners can determine the organization of the message, attend to nonverbal cues, ask questions to get necessary information, and silently paraphrase the meanings they have understood. Basically, listening serves two purposes: 1) gathering facts and information, and 2) demonstrating care and concern. The successful chair realizes that everyone has a different frame of reference and will listen not only to the words, but also to the feelings behind the words. Listening Preferences Just as individuals have different management styles, they also have different listening styles. While everyone has a dominant style, with practice chairs can develop a repertoire to use in different situations. Listening is a skill that can be honed, and listening habits can be modified with incentive, knowledge, and practice. Watson and Barker (1995) have constructed a Listening Style Profile that helps identify one's listening preferences. Their four listening orientations are easily applied to the role of the department chair. The acronym PACT outlines the four types of listening preferences presented in the Listening Styles Profile: People-, Action-, Content-, and Time-oriented. These predilections indicate individual's preferences; however, most people choose contextually. The PACT styles are shown in Tables 1- 4. The tables summarize positive and negative characteristics as well as strategies for communicating. People-oriented listeners. Chairs who are predominantly people-oriented listeners (Table 1) are perceived as nurturing and caring. They will spend hours chatting about personal issues, know the names of faculty members' spouses and children and tend to be liked. This affinity for people can prove frustrating, however, as people-oriented listeners have difficulty accomplishing tasks and struggle with tough decisions. Action-oriented listeners. Action-oriented listeners (Table 2) are very confident and believe they know the best way to get a task done. They are focused on solving problems and are generally extremely productive. Problems arise when faculty feel they are more concerned with projects than people. Content-oriented listeners. Collecting data and playing devil's advocate are two of the strengths of content-oriented listeners (Table 3). Faculty working with these chairs often become frustrated with their inability to bring closure to issues. Typical content-oriented listeners avoid taking risks, enjoy lengthy meetings, and are experts in seeing how each detail of a project fits into the whole picture. Time-oriented listeners. Like action-oriented listeners, time-oriented listeners (Table 4) are able to complete their work tasks efficiently. They are addicted to their daytimers and to-do lists. Faculty working for these chairs often feel rushed and misunderstood. Time-oriented chairs must strive to carve out "listening time" for their faculty and display open nonverbal listening behavior. Although each individual has a dominant listening preference, the successful chair will discern which is needed in each situation. Chairs can improve listening by attending to the following guidelines regardless of listening preference: Stop what you're doing. Show your faculty members by your body language and eye contact that you are listening. Turn your chair to face them, maintain eye contact, and ignore the phone. Put the individual talking to you at ease. Because of your position as chair, even the most casual conversation can be uncomfortable for faculty. Start the conversation by focusing on a subject of interest to them. Focus on main points. Be sure you correctly hear and understand the content of the message. Paraphrase what you have heard to ensure accuracy. Ask probing questions for clarification. Consider the feelings behind the words. Sometimes faculty just need to vent. They may not want you to solve their problems, but just acknowledge that you are interested. Keep your mind open and your mouth closed. Most of the time decisions do not have to be made immediately, and responses to feelings can be delayed. It is wise to listen and later take notes about the meeting. Then, after reflecting, you can respond comprehensively and unemotionally. Don't forget the follow up. Consider if you need to follow the discussion with a note, phone call, or another meeting. Referring to your discussion shows that you listened and are concerned. Follow ups are not always necessary, but a wise chair can discern when an additional response is needed. Understanding your listening preference(s) and practicing active listening will lead to a more successful tenure as chair. The chair who listens and helps others is the chair who is effective and respected. Challenge yourself to make time for your faculty and lend a listening ear. Table 1 People-Oriented Listeners Positive Characteristics Strategies for Communicating with People-Oriented Listeners Negative Characteristics Show care and concern for others Over involved in feelings of others Use stories and illustrations to make points Are nonjudgmental Avoid seeing faults in others Use "we" rather than "I" in conversations Provide clear verbal and nonverbal feedback signals Internalize/adopt Use emotional examples emotional states of others and appeals Are interested in building Are overly expressive relationships when giving feedback Show some vulnerability when possible Notice others' moods quickly Use self-effacing humor or illustrations Are nondiscriminating in building relationships Table 2 Action-Oriented Listeners Positive Characteristics Negative Characteristics Strategies for Communicating with Action-Oriented Listeners Get to the point quickly Tend to be impatient with Keep main points to three rambling speakers or fewer Give clear feedback Jump ahead and reach Keep presentations short concerning expectations conclusions quickly and concise Concentrate on understanding task Jump ahead or finishes thoughts of speakers Have a step-by-step plan and label each step Help others focus on what's important Minimize relationship issues and concerns Watch for cues of disinterest and pick up vocal pace at those points or change subjects Encourage others to be organized and concise Ask blunt questions and appear overly critical Speak at a rapid but controlled rate Table 3 Content-Oriented Listeners Positive Characteristics Negative Characteristics Strategies for Communicating with Content-Oriented Listeners Value technical information Are overly detail oriented Use two-side arguments when possible Test for clarity and understanding May intimidate others by asking pointed questions Provide hard data when available Encourage others to provide support for their ideas Minimize the value of nontechnical information Quote credible experts Welcome complex and challenging information Discount information from Suggest logical sequences nonexperts and plan Look at all sides of an issue Take a long time to make Use charts and graphs decisions Table 4 Time-Oriented Listeners Positive Characteristics Negative Characteristics Strategies for Communicating with Time-Oriented Listeners Manage and save time Tend to be impatient with Ask how much time the time wasters person has to listen Set time guidelines for meeting and conversations Interrupt others Try to go under time limits when possible Let others know listening- Let time affect their ability Be ready to cut out time requirements to concentrate necessary examples and information Discourage wordy speakers Rush speakers by frequently looking at watches/clock Be sensitive to nonverbal cues indicating impatience or a desire to leave Limit creativity in others Give cues to others when by imposing time time is being wasted pressures Get to the bottom line quickly Source: The Department Chair, Winter 1999, Vol. 9, No. 3 Reprinted with permission of Anker Publishing, 176 Ballville Rd., P.O. Box 249, Bolton, MA 01740 www.ankerpub.com