table of contents

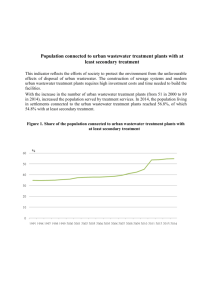

advertisement