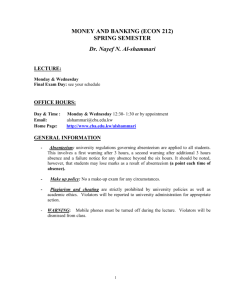

MS - Word - Department of Economics

advertisement