A concern faced by the three major actors of industrial relations is

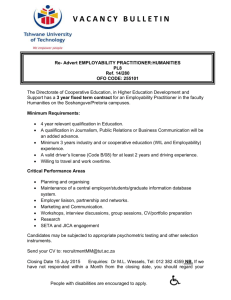

advertisement