The determinants of Foreign Direct Investment in China

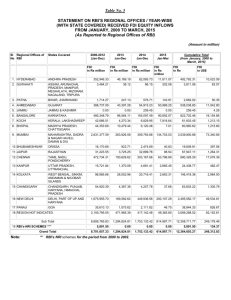

advertisement

The determinants of Foreign Direct Investment in China Jia Ren, Eric Pentecost Economic Department, Loughborough University Abstract After adopting the open door policy, China experienced a boom of inward foreign direct investment (FDI) by multinational corporations since 1980s. From an almost isolated economy, China turned to be the largest recipient of FDI in the developing world. The former research papers concerning on determinants FDI inflow to China contribute the development of FDI to the high growing GDP and the huge population, which supplies not only a huge market, but also the exhaustless and cheap labours for the production as well. However, in reality, there are more economic factors can take into account for the increasing the FDI inflows into China, such as taxes, exchange rates, infrastructure developments etc, from the empirical side, there are more models applied into Chinese data of these variables. This paper is going to have a discussion on the determinant of foreign direct investment (FDI) into China. The long term effect will be observed. Twenty-three-year annual data from 1982 to 2004 are used in the regression analysis of the determinants of FDI stock in China. The results indicate that there is a significant effect of labour, GDP, trade, exchange rate and tax on the national and regional level FDI stock. Key words: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), China 1. Introduction Foreign direct investment (FDI) is defined as "investment made to acquire lasting interest in enterprises operating outside of the economy of the investor."1 The FDI relationship consists of a parent enterprise and at least one affiliate out of its home country. The parent firm imply the business strategies in production, marketing, finance through its affiliates. After adopting the open door policy, China experienced a boom of inward foreign direct investment (FDI) by multinational corporations since 1980s. In the first period 19791983, FDI inflows into China were with limited amount. In the 1982, the inflow FDI to China was 430 million of US dollars. 1983 the inflow come to 606 million of US dollars. The average annual inflow is 518 million. Table1: the average annual inflow in three periods (million US $) Period The average annual inflow 1982-1983 518 1984-1991 2693.25 1992-2006 4777.67 Source: Statistics Bureau of China From 1984, the inflow of FDI started to take off stably from the annual inflow of 1,256 million US dollar (1984) to 4366 million (1991). The annual growth rate from 1985 to 1990 keep positive with the range from 3% to 38%. The average annual inflow is 2,693 million US dollar. Since 1992, the inflows of FDI into China accelerate. The annual inflow started from 11,156 (1992) million of US dollar to 87,286 million (2006). The annual growth rate keep positive during the third period except the rate in 1999 was – 10.14%. Furthermore the rate in 1998 (0.45%) and 2000 (2.63%) was slight positive. This temporary delay may due to the influence from Asian financial crisis. However, from 2001, the inflow of FDI 1 Foreign Direct Investment, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development to China has recovered from the crisis with the annual growth rate of 11.77% and reached a new record of 47,052 million US dollar. In 2005, there is acceleration in the inflow FDI with the 41.32% growth rate and drop to 86,071 million US dollar. The average annual inflow in this period was 47, 775million US dollar. Figure1. The FDI inflow to China 1983-2006 (million US $) 100000 90000 80000 70000 60000 50000 40000 30000 20000 10000 06 05 20 04 20 03 20 02 20 01 20 00 20 99 20 98 19 97 19 96 19 95 19 94 19 93 19 92 19 91 19 90 19 89 19 88 19 87 19 86 19 85 19 84 19 83 19 19 19 82 0 Source: Statistics Bureau of China From an almost isolated economy, China turned to be the largest recipient of FDI in the developing world. The FDI inflow to mainland China in 2006 was 69.47 billion US dollars, which was 18% of the developing countries and 5.32 % of the world. The accumulated FDI inflows to China until 2006, reached 293 billion US dollar, constituting over 9.27 % of total FDI into all developing countries, 2.44% of the world total FDI stocks (UNCTAD 2007). The former research papers concerning on determinants FDI inflow to China contribute the development of FDI to the high growing GDP and the huge population, which supplies not only a huge market, but also the exhaustless and cheap labours for the production as well. However, in reality, there are more economic factors can take into account for the increasing the FDI inflows into China, such as taxes, exchange rates, infrastructure developments etc, from the empirical side, there are more models applied into Chinese data of these variables. 2. The determinants for the FDI inflows Former literatures have keenly discussed the different factors which may influence the multinationals’ investment to the foreign market. The variables include the local market demand, the distance between the home country and the host country, the amount of the local labour and capital endowment, the taxes levied, the exchange rate, local economic growth, the political and the economic risk and the local infrastructure etc. A. Market demand A large or growing host market is a positive factor for the profitable investments. In the empirical studies, market size effect is generally measured by GDP, GDP per capita, GNP, GNP capita or the growth rate of these factors. The empirical results of the studies support the market size have a significant and positive effect on inward FDI to China. The rapid growth of the local economies creates lots of domestic market and business opportunities for foreign investments and hence bolsters investors’ confidence. The positive relationship between market size and inward FDI is confirmed by Dees (1998), Fung (2000), Zhang (2000). B. Distance Distance is a common variable in the empirical studies, although the expected effect for this variable is ambiguous. It may reveal the effects of dissimilarities in culture and institutions and then have a negative effect on multinationals’ investment decisions. However, it may also work as an indicator to measure the effects of shipping cost, and have a positive effect on horizontal foreign investments and have a negative effect on vertical ones. The impact of geographical distance on FDI flows into China was discussed by Wei (1995), Liu et al (1997) and Wei and Liu (2001). The coefficient of the distance variable was found to be significant in studies by Wei (1995, 2005) but insignificant in Liu et al (1997) and Wei and Liu (2001). C. Endowment cost --Labour The results of the effects of relative factor cost on the FDI inflows are ambiguous. Lower labour costs and higher unemployment are recognized to attract the FDI funds in many studies (Huber and Pain 2002; Barrell and Pain 1997, Wheeler and Mody 1992). The studies on FDI in China demonstrated that Chinese low labour costs played an important role in foreign firms’ FDI decision (Liu et al 1997, Dees 998 and Wei and Liu 2001). The researches provided evidence to multinationals removed part of their manufacturing operations away from their home bases or set up a new business in China to exploit international differences in factor prices. Since labour cost is an important part of total production costs, especially in labour intensive manufacturing, the lower the labour cost in the host country, the more attractive for the foreign investment the host country. Zhang (2000) did the test on the importance of the labour cost to the investment with different source regions. He found that labour cost played a much more significant role in attracting FDI from Hong Kong than that from the US because funds from Hong Kong was more concentrated in the labour intensive sectors. In the regional data research, the studies about the impact of labour costs on FDI inflow, however, gives a group of mixed results. Cheap labour inputs have obviously an attraction to the foreign investment. Thus, there could be a negative relationship between the labour costs and the inward FDI. However, a positive relationship is also thought to be possible in the literature as wage rate could be regards as a signal for the labour quality. Higher wage rate may indicate the higher skill labours that foreign investors seek. It is not so accurate to say that FDI is attracted mainly by cheap labours in China. By controlling the productivity, Coughlin and Chen (1997), Wei et al (1999) and Wei and Liu (2001) found that wage rate has a negatively influence on FDI inflow into China. But no significant relationship between FDI and wage cost is found in test by Head and Ries (1996). Also, a positive significant relation is found in Zhao and Zhu (2000). Sun, Tong and Yu (2002) provide the evidence to show that wage is positively related to FDI before 1991 but negatively related with FDI since then. D. the endowment cost ---- capital FDI is basically financed in the home country. If the cost of borrowing in the home country is lower than in the host country, home country firm can have a cost advantage over host country rivals, and are in a better position to enter the host country market via FDI. Thus the higher the ratio of host country borrowing cost to the home country costs, the higher will be inward FDI in the host country. However, this relationship has not been supported by the economists, because in reality multinationals can finance their activities from the international capital market besides the local market. Another opinion insert that the interest rate is an indicator of macroeconomic stability, which influence the FDI in the host country. The higher interest rate in the host country indicates the insatiability, which may result in the reduction of FDI inflow. The discussions about the influence of the interest rate on FDI are ambiguous, therefore, the empirical findings on the influence of the capital inputs are weak as well (Mody and Srinivasan 1998, Devereux and Griffith 1998, Barrel and Pain 1999). Due to the nonconvertible-condition of the Chinese domestic currency, the interest rate works only as one of the government tools for the macroeconomic adjustment. The higher interest rate indicates the booming of the local economy and positive effect on the FDI (Liu et al 1997). E. Tax Several empirical studies have investigated the influence of taxes on foreign direct investment, which is measure by the taxes volume, corporate tax rate or average tax rate. Hartman 1984, Hines1997, 1999, and de Mooij and Ederveen, 2003 studies focus on relationship of the tax volume and distribution of FDI. Bartik (1985) started to introduce the corporate tax rate into the FDI determinant model. He found that there is a significant impact of the tax rate on business location decisions. F. Exchange rate The exchange rate influences the FDI location choice by two methods: the influences of appreciation or depreciation of the currency on the production cost and the volatility of the currency on the investment risk. The results of the exchange rate on the production are quite ambiguous. If FDI aim at producing for re-exports, it is complementary to the international trade. Thus an appreciation of the local currency is supposed to reduce the FDI inflows since it raises the local labour costs. A decrease in the relative labour cost, either through a fall in its relative wages or real exchange rate deprecation, will increase the foreign investment. On the other hand, if FDI aim at serving the local market, FDI and trade are substitute each other. An appreciation of the local currency increase FDI inflows due to higher purchasing power of the local consumers. The depreciation in the real exchange rate of the FDI recipient countries will increase the FDI inflow since it reduced cost of capital investment. Foot and Stein (1991) did the empirical test on the US and Japan during 1989 to 1991, and demonstrated the hypotheses that a depreciated currency can raise the foreign investors’ motivation in buying the control of the foreign corporate assets because that exchange rate changes have the impacts on international wealth and wealthier buyer find it easier to acquire assets. Klein and Rosengren (1992), develop the researches by focusing on the country specific productivity shocks, which was recognized to affect the relative wealth of a country and the amount of foreign direct investment undertaken by its investors. Blonigen (1997) argues that the acquisitions of multinationals involved the foreign firm-specific assets and the changes in the exchange market may prevent the domestic and foreign investors from having equal access to all markets. He applied the data of Japanese acquisitions in the United State from 1975 to 1992 in the test. The result displayed a strong correlation of a weaker dollar and the higher levels of Japanese acquisition FDI in the United States for industries which more likely involve firmspecific assets. The data find that a 10 percent lower dollar increases Japanese acquisition FDI activity in high R&D manufacturing sectors by 18-32 percent. In addition, this effect does not display itself in the green field plants invested by the Japanese funds, where acquisition of firm specific assets is not involved. If foreign and domestic firms have equal opportunity to purchase firm specific assets in the domestic market, but different opportunities to generate return on these assets in foreign markets, then currency movements may affect relative values. In the literatures, Chinese currency Renmingbi (RMB) is generally recognized as undervalued. Cline (2005) found that it is under-valued by 43% with respect to the US dollar. Zhang (2001) found that the cumulative effect of exchange rate reform led to a substantial real depreciation of the Chinese currency since 1981 when the reform was introduced. The undervaluation occurred in 12 of 20 years from 1978 to 1997. These results indicated that China at the moment employed the nominal exchange rate as a policy tool, which varied either frequently or occasionally, to attain a real exchange rate target. A real depreciation of Chinese currency will favour the foreign firms’ purchase of the host country’s asset and allows foreign investors to take advantage of the relatively cheap labours in the host country (Liu et al 1997, Dees 1998 and Wei and Liu 2001). Therefore, depreciation was expected to be positively associated with FDI inflow. Liu et al (1997) and Wei and Liu ( 2001) obtained a positive coefficient on the exchange rate variable in the regression equations designed to test the determinants of FDI into China. Some literatures focus on the influence of the exchange rate volatility on the FDI investment. The higher volatility in exchange rate usually indicates that the home and host countries lack the economic similarity. In addition, multinationals may also regard the exchange rate volatility as an indicator to measure the macroeconomic instability in the host country. Furthermore, the effect of exchange rate volatility may have the influence on the relative price of intermediate inputs imported from the parent country or final products which will be exported back to the parent country. All these aspects of exchange rate volatility will have a negative impact on multinational activity. However, under the assumption of uncertainty of exchange rate and inflation rate, multinationals may respond to the increase risk in the real exchange rate appreciation though reducing exports of final goods to the foreign country, they can offset this by increasing foreign capital investment and raise the final goods production level in the host countries (Cushman 1982). Multinationals may perceive influence of the exchange rate volatility on trade cost, and choose to produce abroad instead of exporting, if exchange rate volatility is high. Benassy Quere, Fontagne and Lahureche-Revil (1999) did the research on the exchange rate in the 42 emerging countries receiving FDI from 17 investing countries and found out the 1% appreciation in the real exchange rate reduced the FDI stock by 0.23%, where a 1 point increase in exchange rate volatility reduce the investments by 0.63%. However, it was observed that the emerging countries’ domestic economy at the same time suffers from a positive inflation due to the investing countries. Therefore, to prevent the real exchange rate from appreciation indicate that the nominal exchange rate must depreciate periodically, which will induce some volatility. There are limited papers about the relationship between the FDI and the volatility of the exchange rate in China. However, some empirical test focus on the influence of exchange volatility on the Chinese exports, which has close relationship with the FDI inflow to China. The a negative long run effect of exchange rate volatility on Chinese total exports was found in empirical tests, which means that exchange rate uncertainty impedes trade (Chou 2001). Usually, foreign trade can avoid or minimize the exchange rate uncertainty in trading transition by hedging in the forward exchange market. However, the forward market for the Chinese currency, which is not fully convertible, has not yet been developed. Thus the trading activity that requires decisions to be made with respect to long term time horizons is unprotected by forward market. As long as traders are unable to eliminate exchange rate uncertainty, large exchange rate variability will result in less trade. For this reason, the long run responses of China’s exports to exchange rate variability have been found to be negative. This may result in a shifting for the investor to increase the investment to avoid the financial risk in the currency market. Thus the volatility of the local currency may raise the FDI to China if it has a complementary relationship with trade. G. The other variables: The studies of the FDI inflow determinants have covered the effects of other macroeconomic variables such as local economic growth, the political and economic risk of host country and the infrastructure etc. The higher economic growth reflects improvement in productivity and development. Lower economic and political risks will result in a more attractive and stable climate for foreign investors. The infrastructure in the host country will influence the extra expenditure of the multinationals. The basic infrastructure constructions are necessary for attracting the investment. The empirical literature concerning about the determinant of FDI become more and more delicate. The research concern about China did growth up as well. However, there is some gap for the future development. First, from the determinant, there are seldom paper point out the exchange rate, tax rate, infrastructure concerned about the FDI into China, although there are some paper did the research on the undervalue measure of Chinese currency and it’s influence on the trade system. Second, the papers concerning the region effect focus on the description of the inequality of the FDI distribution, but seldom analysis the determinant in different regions. This paper is going to have a discussion on the determinant of foreign direct investment (FDI) into China. The long term effect will be observed. Twenty-three-year annual data from 1982 to 2004 are used in the regression analysis of the determinants of FDI stock in China. 3. Methodology 3.1 Model and methodology We can build the following specification due to the discussion in the former literature: FDIit = f (RWAit, RTit, RGDPit, ERit,VARERit, RXit, RMit, RFXit, RFMit) (1) Where FDI = the annual stock of real foreign direct investment in China, RWA = the ratio of real Chinese average wage rates, RT = the ratio of real Chinese tax, RGDP = the ratio of real Chinese GDP, ER = the exchange ratio of Chinese RMB/US $, VARER= the volatility of exchange rate, RX = real Chinese exports, RM = real Chinese imports, RFX = real exports of foreign funded enterprises in China, RFM = real imports of foreign funded enterprises in China, The log-linear form of (1) is: lnFDIit = α+ β1 RWAit+ β2 RTit+ β3lnRGDPit+ β4 ERit+ β5 VAREX it+ β6 ln RXit+ β7ln RMit+ β8lnRFXit+ β9 lnRFMit+ εt, (2) The test is going to take two steps. First, the specification is used to test determinants for the national level of FDI stock in China. The tax effect will be move out of the specification, due to the different tax levels within China. The specification is going to be handled in the econometric test by time-series method. The second step is going to test the determinants for the FDI distribution inside China. In this case, exchange effect tends to be removed from the equation, due to the same currency inside China. The test will be handled in the panel econometrics method. 3.2 data The national and regional data for the nominal FDI stock, GDP, average wage, tax, trade and CPI is from the Statistics Bureau of China. The daily exchange rate data is from datastream. The volatility of the exchange rate is calculated as the annual variance of the exchange rate of the daily exchange rate. World CPI is from Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. For the first step of test, the national level data is collected from 1982 to 2004. For the second step tests, the regional is collected by 30 provinces in the mainland of China from 1994 to 2005. However, to get proper econometrics results, the data from Tibet and Qinghai provinces would be removed from the econometrics because of the slight amount of FDI investment in Qinghai and Tibet provinces. The specification is going to hand the panel data in 30 provinces from 1994 to 2005. 4. Empirical Results Following the discussion in section 3, we got the results for the test. 4.1. national level determinants of FDI stock in China Table 2 estimation of the determinants of FDI into China (1982-2004) Independent coefficients variables lnGDP 4.32*** (9.31) lnX 0.65*** (2.32) lnM -0.29 (-1.29) lnFx lnFm lnWa Ex Varex C R2 -82.02*** (-9.03) 0.42*** (11.39) -0.02 (-0.95) -25.27*** (-9.14) 0.99 coefficients 3.19*** (9.70) 0.13** (2.52) 0.02 (0.16) -61.50*** (6.78) 0.42*** (15.78) -0.02 (-1.12) -24.93*** (-9.35) 0.99 We can found in the results that the GDP as positive effects of the FDI stock. As we mentioned in the second part, the growing market demand encourage the foreign investment to the Chinese market. The test result on the trade tells that the Chinese export has positive effect on the FDI stock. Even, the exports by the foreign fund enterprise have the positive relationship with the FDI stock. However, coefficients of national imports and the imports of foreign fund enterprises in China are not significant in the FDI stock. The average rage has significant positive effect for the FDI stock. This indicates that FDI aim at cheap labour cost rather than the specific high quality labour in China. Exchange rate has significant positive effect on the FDI stock. In this case, the deprecation of the currency did attract the inflow of FDI. However, the coefficient of volatility in exchange rate does not significant. 4.2. Regional level of FDI stock distribution inside China From the econometrics results it is obvious that GDP, Tax, wage level and trade volume have the influence on the FDI distribution inside China. The positive effect of GDP on the FDI stock indicates that the FDI stocks distribution follow the development of the districts, which is the same as the first step test. Also the coefficients of Tax and average wage level are siginificant. The result indicates that the foreign investments look for the lower Tax and wage level regions inside China to reduce the production cost. For the trade level, it is obvious that FDI more focus on the trade by the foreign funded enterprises but not the district trade volume. This is quite different with the results in the national level test. Also the trade volume of foreign funded enterprise has the positive effect on the FDI stock, which indicates that the FDI stocks are more complementary to the trade rather than substitute. Table3: the estimation of the determinants of FDI distribution inside China OLS lnGDP 0.60*** (5.28) lnT -0.26*** (-2.73) lnWa -0.48*** (- 4.13) lnX -0.01 (-0.18) lnM 0.05 (0.62) lnFx 0.16*** (2.66) lnFm 0.45*** (7.95) C 23.29*** (6.54) 2 R 0.88 Fix 0.60*** (5.35)) -0.26*** (-2.73) -0.48*** (- 4.13) -0.01 (-0.18) 0.05 (0.62) 0.16*** (2.66) 0.43*** (4.45) 0.88 Random 0.60*** (5.35) -0.26*** (-2.77) -0.48*** (- 4.19) -0.01 (-0.18) 0.05 (0.62) 0.16*** (2.70) 0.43*** (4.45) 23.29*** (6.23) 0.88 OLS 0.84*** (5.35) -0.32*** (-2.36) -0.85*** (- 5.39) 0.06 (0.63) 0.59*** (6.54) Fix 0.84*** (5.35) -0.32*** (-2.36) -0.85*** (- 5.39) 0.07 (0.69) 0.59*** (6.54) 30.65*** (6.43) 0.77 0.77 Random 0.84*** (5.35) -0.32*** (-2.36) -0.85*** (- 5.39) 0.07 (0.69) 0.59*** (6.54) OLS 0.61*** (5.47) -0.26*** (-2.74) -0.43*** (- 4.45) 0.19*** (3.77) 0.47*** (9.62) 30.65*** 22.26*** (6.43) (7.07) 0.77 0.88 Fix 0.61*** (5.47) -0.26*** (-2.74) -0.43*** (- 4.45) Random 0.61*** (5.47) -0.26*** (-2.74) -0.43*** (- 4.45) 0.19*** (3.77) 0.47*** (9.62) 0.19*** (3.77) 0.47*** (9.62) 22.26*** (7.07) 0.88 0.88 5. Conclusions The paper took the two steps tests on the FDI stock in China: national level and regional level. The growing market size, lower labour cost has positive effect on the FDI stock. Also, FDI stock is attracted by the depreciation of Chinese currency and lower tax region. However, the relationship of trade and FDI are quite ambiguous. In the national level, FDI has positive relationship with export. The effects of imports are not significant. This indicates the FDI are more re-exporting orientated, furthermore, MNCs would preferred the raw materials in China. In the regional the results seems to be opposite. The MNCs regional imports have positive effects on the FDI distribution. For the further development, the specification could include politic and governmental risk system to measure the macro investment environment. Also the country pair method can be used in the research. References: BARRELL, R. and PAIN, N., 1999. Trade restraints and Japanese Direct Investment Flows European Economic Review, 43, pp. 29-45. BARRELL, R. and PAIN, N., 1997. Foreign Direct Investment, Technological Change, and Economic Growth within Europe. Economic Journal, 107(445), pp. 1770-86. BENEASSY- QUERE, A., FONTAGNE, L., LAHRECHE-REVIL, AMINA. KEYWORDS : EXCHANGE RATE REGIME, FDI and C, 1999. Exchange rate strategies in the competition for attracting FDI. CEPII research center. BLAKE, A.P. and PAIN, N., Investigating structural changes in UK export performance: the role of innovation and direct investment. National Institute of Economic and Social Research. BLOMSTROM, M., 1986. Foreign Investment and Productive Efficiency: the case of Mexico. Journal of Industrial Economics, 15, pp. 97-110. BLOMSTRÖM, M. and LIPSEY, R.E., 1989. The export performance of US and Swedish Multinationals. Review of Income and Wealth, 35, pp. 245-264. BLOMSTROM, M. and PERSSON, H., 1983. Foreign Investment and Spillover Efficiency in an Underdeveloped Economy: Evidence from the Mexican manufacturing industry. World Development, 11, pp. 493-501. BLOMSTROM, M. and SJOHOLM, F., 1998. Technology Transfer and Spillovers, Does Local Participation with Multinationals Matter? European Economic Review, 43, pp. 915923. BLONIGEN, B.A., 1997. Firm- Specific Assets and the Link Between Exchange Rates and foreign Direct Investment. American Economic Review, 87(3), pp. 447-465. BRAINARD, S.L., 1993. A Simple Theory of Multinational Corporations and Trade with a Trade-Off Between Proximity and Concentration. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series, No. 4269. CARR, D.L., MARKUSEN, J.R. and MASKUS, K.E., 1998. Estimating the KnowledgeCapital Model of the Multinational Enterprise. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. CAVES, R.E., 1974. Multinational Firms Competition and Productivity in Host-Country Markets. Economica, 41, pp. 176-193. CEGLOWSKI, J. and GOLUB, S., 2007. Just How Low are China's Labour Costs?. The World Economy, 30(4), pp. 597-617. CHEUNG, K. and LIN, P., 2004. Spillover effects of FDI on innovation in China: Evidence from the provincial data. China Economic Review, 15(1), pp. 25-44. CHOU, W.L., 2000. Exchange Rate Variability and China's Exports. Journal of Comparative Economics, 28(1), pp. 61-79. COHEN, B.I., 1973. Comparative Behavior of Foreign and Domestic Export Firms in a Developing Economy. The review of economics and statistics, 55(2), pp. 190-97. COUGHLIN, C.C. and SEGEV, E., 1999. Foreign direct investment in China: a spatial econometric study. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. CUMMINS, J.G., HASSETT, K.A. and GLENN, R., 1996. Tax Reforms and Investment: A Cross-Country Comparison. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. CUSHMAN, D.O., 1986/9. Has exchange risk depressed international trade? The impact of third-country exchange risk. Journal of International Money and Finance, 5(3), pp. 361-379. CUSHMAN, D.O., 1985. Real exchange rate rish, expectations, and the level of direct investment. Review of Economics and Statistics, 67(2), pp. 297-308. DE MOOIJ, RUUD A and EDERVEEN, S., 2003. Taxation and Foreign Direct Investment: A Synthesis of Empirical Research. International Tax and Public Finance, 10(6), pp. 673-93. DEES, S., 1998. Foreign Direct Investment in China: Determinants and Effects. Economics of Planning, 31(2), pp. 175-94. DEVEREUX, M., GRIFFITH, R. and SIMPSON, H., 2004. Agglomeration, regional grants and firm location. Institute for Fiscal Studies. DUMAS, B., 1978. The Theory of the Trading Firm Revisited. Journal of Finance, 33(3), pp. 1019-30. EDWARDS, S., 1988/11. Real and monetary determinants of real exchange rate behavior: Theory and evidence from developing countries. Journal of Development Economics, 29(3), pp. 311-341. FINDLAY, R., 1978. Relative Backwardness, Direct Foreign Investment and the Transfer of Technology: a Simple Dynamic Model. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 92, pp. 1-16. FROOT, K.A. and STEIN, J.C., 1991. Exchange Rates and Foreign Direct Investment: An Imperfect Capital Markets Approach. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(4), pp. 1191-217. FUNKE, M. and RAHN, J., 2002. Just How Undervalued is the Chinese Renminbi. The World Economy, 28(4), pp. 465-489. GLOBERMAN, S., 1979. Foreign Direct Investment and ‘Spillover’ Efficiency Benefits in Canadian manufacturing industries. Canadian Journal of Economics, 12, pp. 42-56. GOLDSTEIN, M. and LARDY, N., 2006. China's Exchange Rate Policy dilemma. American Economic Review, 96(2), pp. 422-426. GOLDVERG, L.S. and KLEIN, W.M., 1997. Foreign Direct Investment, Trade and Real Exchange Rate Linkages in Southeast Asia and Latin America. NBER Working Paper No. W6344, . GRUBERT, H. and MUTTI, J., 1991. Taxes, Tariffs and Transfer Pricing in Multinational Corporate Decision Making. The review of economics and statistics, 73(2), pp. 285-93. HEAD, K. and RIES, J., 1996. Inter-City Competition for Foreign Investment: Static and Dynamic Effects of China's Incentive Areas. Journal of Urban Economics, 40(1), pp. 3860. HELPMAN, E. and KRUGMAN, P.R., 1985. Market structure and foreign trade: increasing returns, imperfect competition, and the international economy. Cambridge ( Mass), MIT Press. HINES, J.R.,JR and RICE, E.M., 1994. Fiscal Paradise: Foreign Tax Havens and American Business. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109(1), pp. 149-82. HU, A.G.Z. and JEFFERSON, G.H., 2002. FDI Impact and Spillover: Evidence from China`s Electronic and Textile Industries. The World Economy, 25, pp. 1063-1076. HYMER, S.H., 1976. The International Operations of National Firms: A Study of Direct Foreign Investment. KINDLEBERGER, C.P., ed, 1970. The international corporation: a symposium. M.I.T. Press. KINDLEBERGER, C.P., 1969. American business abroade: six lectures on direct investment. Yale U.P. KLEIN, W.M. and ROSENGREN, E.S., 1994. The Real Exchange Rate and Foreign direct Investment in the United States: Relative Wealth vs Relative Wage Effects. Journal of International Economics, 36, pp. 373-389. LI, X., LIU, X. and PARKER, D., 2001. Foreign direct investment and productivity spillovers in the Chinese manufacturing sector. economic systems, 25(4), pp. 305-321. LIN, P., 2001. R & D in China and the Implications for Industrial Restructuring at the Dawn of China's Accession to the WTO. East Asian Bureau of Economic Research. LIPSEY, R.E. and SJOHOLM, F., 2001. Foreign Direct Investment and Wages in Indonesian Manufacturing. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. LIU, X., SILER, P., WANG, C. and WEI, Y., 2000. Productivity spillovers from foreign direct investment: evidence from UK industry level panel data. Journal of International Business Studies, 31, pp. 407-425. LIU, X., WANG, C. and WEI, Y., 2001. Causal links between foreign direct investment and trade in China. China Economic Review, 12, pp. 190-202. LIU, X., SONG, H., WEI, Y. and ROMILLY, P., 1997. Country characteristics and foreign direct investment in China: A panel data analysis. Review of World Economics, 133(2), pp. 313-329. LO, D., 1999. Reappraising the performance of China’s state-owned industrial enterprises 1980–1996. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 23, pp. 693-718. MARKUSEN, J.R., 1984. Multinationals, multi-plant economies, and the gains from trade. Journal of International Economics, 16(3-4), pp. 205-226. MARKUSEN, J.R. and VENABLES, A.J., 1996. The Increased Importance of Direct Investment in North Atlantic Economic Relationships: A convergence Hypothesis, Ethier, W. J and Grilli, V. (eds). The New Transalantic Economy, . MCKINNON, R., 2006. China's Exchange Rate Policy Trap: Japan Redux? American Economic Review, 96(2), pp. 427-431. MODY, A. and SRINIVASAN, K., 1998. Japanese and United States Firms as Foreign Investors: Do they march to the same tune? Canadian Journal of Economics, 31(4), pp. 778-799. SUN, Q., TONG, W. and YU, Q., 2002. Determinants of foreign direct investment across China. Journal of International Money and Finance, 21(1), pp. 79-113. WANG, J. and BLOMSTROM, M., 1992. Foreign investment and technology transfer: a simple model. European Economic Review, 36, pp. 137-155. WEI, Y. AND LIU, X., 2001. Foreign Direct Investment in China: Determinants and Impact. Edward Elgar, UK, . WEI, Y., LIU, X., SONG, S. and AND ROMILLY, P., 2001. Endogenous Innovation Growth Theory and Regional Income Convergence in China. Journal of International Development, 13(2), pp. 153-168. ZHANG, K.H., 2001. China’s inward FDI boom and the greater Chinese economy. Chinese Economy, 34(1), pp. 74-88. ZHANG, K.H., 2001. What explains the boom of foreign direct investment in China? Economia Internazionale, 54(2), pp. 251-274. ZHANG, Z., 2001. Real Exchange Rate Mislignment in China: An Empirical Investigation. Journal of Comparative Econimics, 29, pp. 8-94. ZHANG, A., ZHANG, Y. and ZHAO, R., 2001. Impact of Ownership and Competition on the Productivity of Chinese Enterprises. Journal of Comparative Economics, 29(2), pp. 327-346. ZHANG, K.H., 2000. Why Is U.S. Direct Investment in China So Small? Contemporary Economic Policy, 18(1), pp. 82-94. ZHANG, K.H. and MARKUSEN, J.R., 1997. Vertical Multinationals and Host-Country Characteristics. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. ZHANG, K.H., 2001. How does foreign direct investment affect economic growth in China? The Economics of Transition, 9(3), pp. 679-693. ZHANG, K.H., 2001. What Attracts Foreign Multinational Corporations to China? Contemporary Economic Policy, 19(3), pp. 336-46. ZHANG, K.H. and SONG, S., 2001. Promoting exports: the role of inward FDI in China. China Economic Review, 11(4), pp. 385-396. ZHAO, H. and ZHU, G., 2000. Location factors and country-of-origin differences: An empirical analysis of FDI in China. Multinational Business Review, Spring. Appendix: Variable definitions: FDI: the real annual inflow of foreign direct investment in China derived from nominal FDI stock deflated by the world CPI index in US dollars. Source: Chinese Statistics Yearbook 1996- 2006. RGDP: the relative real GDP, defined as the nominal deflated by Chinese CPI index, the GDP was converted to US dollars from the local currency Yuan. Source: Chinese Statistics Yearbook 1996- 2006. RWa: the average real wage rate, defined as nominal average Chinese wages rates deflated by Chinese CPI index, the wage was converted to US dollars from the local currency Yuan. Source: Chinese Statistics Yearbook 1996- 2006. RT: the real Tax amount, defined as the nominal Tax deflated by the Chinese CPI, the wage was converted to US dollars from the local currency. Source: Chinese Statistics Yearbook 1996- 2006. Ex: the real exchange rate, defined as the ratio of the Chinese currency (Yuan)/US $. Source: datastream. Varex: the volatility of exchange rate, defined as the annual variance of exchange rate. Source: datastream. RGDP: the relative real GDP, defined as the nominal deflated by Chinese CPI index, the GDP was converted to US dollars from the local currency. Source: Chinese Statistics Yearbook 1996- 2006. RX: Chinese real exports, defined as the nominal exports deflated by Chinese CPI index, the RX was converted to US dollars from the local currency. Source: Chinese Statistics Yearbook 1996- 2006. RM: Chinese real imports, defined as the GDP deflated by Chinese CPI index, the RM was converted to US dollars from the local currency. Source: Chinese Statistics Yearbook 1996- 2006. RFx: real exports by foreign funded enterprise in China, defined as the nominal Fx deflated by Chinese CPI index, the RFx was converted to US dollars from the local currency. Source: Chinese Statistics Yearbook 1996- 2006, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. RFx: real imports by foreign funded enterprise in China, defined as the nominal Fm deflated by Chinese CPI index, the RFm was converted to US dollars from the local currency. Source: Chinese Statistics Yearbook 1996- 2006.