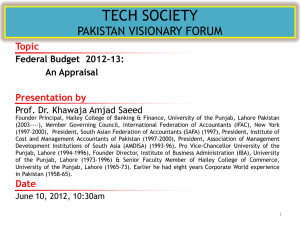

Vol.2,No.2 - Lahore School of Economics

advertisement