G:\respcare\chart_ interview

advertisement

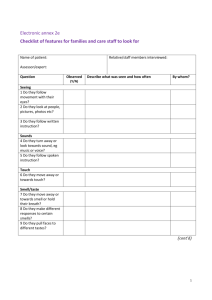

RSPT 1429 Fundamentals I Unit 1: Part IV: checking the chart and the interview: Lecture notes by Elizabeth Kelley Buzbee A.A.S., R.R.T.-N.P.S., R.C.P. Checking the chart Before entering the patient’s room to perform a therapy, the RCP must collect some essential data from the patient’s chart. For all treatments, the first time the RCP approaches the patient, he must look for [1] physician’s orders [2] last RCP’s documentation and [3] nurse’s graphic for most recent vital signs and the trend of vital signs and [4] progress notes. After a quick glance at the chart, as the RCP enters the patient’s room, he will have a mental picture of the patient. Age, gender, mental status and respiratory status should all be known. If the RCP was to enter the wrong room, she would know immediately that the elderly black woman is not the 24 year old white male that was described in the chart. If the RCP entered the correct room to find the patient unconscious, he would not be upset if the chart has already warned him that this patient is comatose. On the other hand, if the patient has had a sudden drastic change in status, prior knowledge of the patient’s baseline helps the RCP make a quicker decision about calling for help. Physicians’ order sheet The physicians order sheet is the only ‘official’ place to check the order. All other records only refer back to the original order. Inhaled drugs can be ordered by generic or by brand name and the amount and frequency of the dose needs to be present. If the doctor only ordered the drug, we would give it once. Frequency of TX Q day Q 4hr QID TID BID Q AM HS PRN stat ASAP How often? Once a day Every 4 hours 4 x a day 3 x a day 2 x a day Once a day in the morning Given at the hour of sleep As needed Emergency! do it now! As soon as possible EXAMPLES of typical orders: date time order 2/23/07 1435 1. Assess Vital signs Q 4 hrs. Call me if the BP rises over 180/100 mmHg 2. Measure Sp02 now and if it is below 91%, start patient on oxygen at 2 lpm nasal cannula. Repeat Sp02 QAM 3. Give 2.5 mg Albuterol in 2.5 ml normal saline now & Q 6 hr & PRN 4. start patient on low Na diet-----------------------------Robert Hale MD 2/23/07 2300 Get an EKG stat -------------------T/O to Jill Mac RN from Robert Hale MD In addition to the MD’s hand writing, the RCP will note that the other health care workers will “sign off “on these orders as they are filled the first time. While they try to write each order on a separate line, please note that the VS order on line 1, also includes an order to notify the doctor if the patient becomes hypertensive. The second order also includes three different actions. Note that the order for an EKG at 2300 [11:00 PM] was called in by telephone [T/O] and the RN that took the message signed her name and credentials. While nurses can take any verbal or phone order, the RCP should only take verbal orders for actions the RCP can perform. These duties will vary from hospital to hospital. Respiratory Care sheet We have already looked at examples of the respiratory flow sheet. This part of the chart may be skipped if the RCP got a good oral report from the last RCP who had the patient. The actual format of the respiratory flow sheet will vary from institution to institution and even within the hospital. The form the RCP would chart treatment in the ICU might differ from the one we would use for floor patients. Nurse’s Graphic The RCP will check the last entry on the nurse’s graphic as well as get a range of heart rates, respiratory rates and blood pressure for the patient for the last few hours. This gives her a baseline from which to judge the changes in the vital signs [VS] that she will gather during her own assessment of the patient. Progress notes The doctor will usually include the initial history and physical at the front of the progress notes. As lab values come in he may or may not include these. Frequently, the MD will put his progress notes in the format of SOAP charting or in the format of POMR [problem-orientated medical record] The RCP needs to glance briefly at the progress notes to find indications, contra-indications and hazards or cautions for the ordered therapy because sometimes the therapy that has been ordered is impossible to follow. We also need to see what the doctor’s plans are for our patient. Other Data Depending on the therapy ordered and the potential hazards of that therapy, we may need to access other data. For instance, if one starts supplementary oxygen for a patient, he might want to check the lab work for arterial blood gases to get an idea about the potential safety and effectiveness of the oxygen to be started. If we need to draw an arterial blood gas, we need to check the medication sheet for drugs that can limit blood clotting. If the RCP has a patient who is ordered on a therapy that could cause a pneumothorax [air leak in the chest wall] she would need to check the X-ray report for potential problems that put the patient at increased risk for these hazards. List at least 5 areas in a standard patient chart and identify the data one could find in each section. Area of chart Physicians’ orders History & Physical or progress notes Lab reports Medication sheets X-ray reports EKG reports Special TX sheets Nurse’s graphic Surgery/ anesthesia report Post op /recovery room report Information to be found here Date, time and exact prescription will be found here. If the drug can be substituted by generic drug, you will find it here. The doctor’s signature will be here. If the nurse or the RCP took a phone order, it will be designated as T/O [telephone order.] which the MD will eventually have to sign. As the patient is transferred, new orders will be written. Several different doctors will write orders in this document. The doctor will use these sheets to describe the patient’s appearance and to discuss his plans for both diagnostics and for treatment. Changes in the patient will be detailed in these signed sheets over the course of the patient’s admission. Occasionally, some therapists [respiratory/occupational/physical] may need make brief notes in this section-particularly if they are recommending changes in the care. All blood work will be found in this section of the chart, although many hospitals are moving to computer records for this data. The lab data may have normal values, but generally lacks any interpretations. Lab work includes : complete blood counts, arterial blood gases, serum levels of drugs, electrolytes The MRI is the nurse’s medication sheet and as she gives the drugs, she will initial in the time frame. All imaging reports will be signed by a radiologist who will dictate a brief discussion and diagnosis based on the findings. Electrocardiograms of the action of the heart will be found here. The machine will interpret the EKG, but until the cardiologist signs it, the interpretation is not valid. Respiratory care departments will design their own documentation that will appear in this section. Other departments such as physical therapy, occupational therapy and rehabilitation will all have their own documentation. Based on the frequency ordered by the doctor, the nurses who takes care of your patient will be charting the vital signs [VS] which consist of heart rate [HR,] respiratory rate [RR,] blood pressure [BP] temperature and sometimes pulse oximetry [Sp02.] I/O: urine out put and liquid input will be included here A detailed report of each surgery will be included here. This will include the initial diagnosis and the final diagnosis based on the finding during surgery. The anesthesiologist who administered drugs will keep a running tally of the VS, and other data during the surgical procedure. After surgery, the patient is transferred to the recovery room where frequent VS and breath sounds as well as other data is collected by the nurses in this area. The physical exam starts with the interview. Your initial impression with the patient is critical if you expect to be taken seriously. Be clean, well-groomed and professionally dressed. The hospital is not a place to display originality; we wear uniforms for a reason. Follow grooming guidelines for your institution. [Reference to student handbook] Sick people are not in the mood for fashion statements nor controversy. Keep your fancy hairdo and political buttons at home. Fake nails are health hazards and forbidden in most hospital. Hair should be off the face, it too is a health hazard. Have your badge[s] visible to the patient or family member. 1. Introduce yourself by name and department. You are in a social situation and how you initially approach the patient will determine your relationship with them. We knock on the door and verbally announce ourselves. Give the patient his privacy if he is not quite ready for you. If he is in the bathroom or on the bedpan, excuse yourself and leave the room. The RCP moves into the patient’s space by first standing close to the door to introduce herself by both name and department. [4-12 feet] “Hello, Mr. Harris, I’m Katie Hill from the respiratory therapy department…may I come in?” It is not necessary to identify yourself as a student, but always admit this if the patient or the family member asks you. 2. Wash your hands before touching the patient. While hand washing, the RCP could begin to establish a relationship, by telling the patient why he is in the room. “Mr. Harris, the doctor has ordered a breathing treatment for you and we need to do it now.” 3. Establish rapport before touching the patient. The social space is used between persons who are not discussing intimate details. “Hi, how are you?” “Nasty weather we are having; aren’t you glad you’re not out in it?” Move from social [4-12 feet] to personal [18 inches-4 feet] to intimate [0 to 18 inches] slowly; this gives the patient a chance to check you out before you move closer to the bedside. Limit discussions of potentially confidential information to the personal and intimate spaces to preserve your patient’s privacy and to encourage him to confide in you. Even if the patient’s roommate is friendly, it is none of their business when your patient quit smoking. Realize that moving into the patient’s space can trigger feelings of territory in some persons. Be prepared to permission to wash your hands in “her sink”, sit in “her bedside chair.” Realize that patients feel vulnerable because they are undressed & in bed, in what is essentially a public area. The door cannot be locked; the bedside table and the closets cannot be locked. Sometimes, exerting a little control over their environment is emotionally necessary. If you meet resistance and if it is possible, give the patient some options. “Mr. Harris, we need to measure your inspiratory capacity; would you like to do this now or in 30 minutes.” Just having a choice makes a huge difference in a patient’s morale. 4. Check the patient by name band and by verbal response Put on gloves before touching the patient. Before starting the interview with the patient, the RCP must establish identify of the patient by checking the name band on the wrist and by verbal questioning. You will have to move into his personal space [1.5-4 feet] and then into his intimate space [0-1.5 feet] Ask his permission before touching him, “Mr. Harris, may I check your name band, please?” Never assume that your patient is telling the truth about who he is. Patients may be confused, deaf, or unable to understand English. You may not speak clearly, the TV is too loud or the patient is one the phone when you ask who they are. Odd as it seems—occasionally-- a patient may actually be joking about who they are. Always check the name band before continuing. It is a good idea to get into the habit of checking not only the name band but the hospital number. There are a lot of Harrises in the world and one of them might be just down the hall. Do not call the adult patient by his first name. Refer to him as Mr. or Mrs. Jones. If the name is difficult to pronounce, ask them how to say their name and repeat it correctly. If you have a real problem with pronouncing the name correctly, it is more respectful to refer to them as “Sir”, or “Ma’am.” 5. Announce your reason for entering their room. If this step wasn’t done during hand washing, now tell the patient why you are here and what you need the patient to do. Be prepared to answer questions in simple terms. Be honest, but don’t dwell on pain or discomfort. “This may be a little uncomfortable, but I will be as quick as possible, Mr. Harris.” 6. Assess the patient for non-verbal feed back. Most everyone understands non-verbal communication, although this skill seems easer for some than others. We look not only at the face for smiles or frowns, but at the set of one’s arms and legs. Generally, crossed arms or legs imply the listener doesn’t agree. Failure to make eye contact is another sign that the speaker needs to increase rapport with her patient. Look at this little girl. Do you think she will follow your directions readily? Why or why not?