PREVENTING FINANCIAL ABUSE

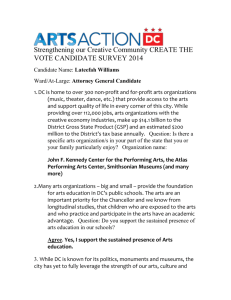

advertisement

PREVENTING FINANCIAL ABUSE TLT SOLICITORS & LYONS DAVIDSON DISCUSSION FORUM 14 NOVEMBER 2013 THE ROLE OF THE COURT OF PROTECTION IN FINANCIAL ABUSE CASES BARBARA RICH, BARRISTER 5 STONE BUILDINGS, LONDON FINANCIAL ABUSE OF VULNERABLE ADULTS – “BAD SAMARITANS AND BLING” ‘Shopaholic’ Julia Patterson – Daily Mail 6 October 2013 “A shopaholic who robbed an elderly relative of almost half a million pounds has been jailed for two years. Julia Patterson, 43, siphoned the money from a 88-year-old relative and spent it on designer clothes. Social services became suspicious of Patterson when she gained power of attorney for the victim in September 2011. They then alerted South Yorkshire Police, who launched an investigation. Economic Crime Unit officers investigated the victim's bank accounts and found that £251,331 had been transferred directly to Patterson. A further £212,039 was paid by cheque to unknown payees, £4,566 was made in cheque payments to Patterson herself and £3,615 to an unknown credit card. The total amount taken from the woman's accounts was £471,552. The 88year-old victim, who lived in a Sheffield care home, and was only given a small living allowance by Patterson. It later emerged that Patterson was in arrears with paying for the relative's care.” -1- ‘Greedy’ estate agent Darren Aston – Daily Mail 15 January 2013 “A callous estate agent left two vulnerable pensioners destitute after conning the elderly pair out of their £260,000 life savings and using the cash to prop up his failing business. 'Greedy' Darren Aston, 42, befriended a 92-year-old widow and her 87-year-old male friend in 2006, running errands for them, accompanying them on hospital visits, and even cooking Sunday lunches for them in their own homes. But after being awarded sole power of attorney over their assets when the elderly pair's health began to deteriorate two years later, Aston drained their bank accounts in just 10 months. He claimed the money had been given to him as a loan, and insisted he had permission to take out the cash in 'bits and bobs'. But investigators discovered Aston's withdrawals from his victims' accounts actually amounted to more than £100,000. He was subsequently arrested and charged with fraud.” The first of these stories is a depressingly frequent example of “bling”: stealing from a vulnerable older person to pay for ostentatious luxuries such as designer clothes. JM and MJ v. The Public Guardian (see below) is one of the most flagrant examples of this: a case where two deputies purchased Rolex watches and designer handbags for themselves out of the assets of an elderly family member whose gifts to them when she had had capacity had taken the form of tea and cake at National Trust properties and a fan-heater for a daughter’s room at university. The second story is a no less depressingly frequent example of the Bad Samaritan: the officious neighbour who appears to be acting as a Good Samaritan toward vulnerable older people, but who is stealing their money whilst gaining their trust. ITW v. Z (see below) is a flagrant example of this. The vulnerability to financial abuse of adults who lack capacity is news in the sense that it fills news pages (many similar cases are reported in local newspapers but do not always attract national coverage), but is sadly not news to those who practise in this field. As these two recent examples show, it is perpetrated both by family members and nonfamily members such as carers, neighbours and local befrienders. The sums involved are often substantial: life savings, and/or the liquid proceeds of properties sold when an elderly person leaves home for institutional care. The system of abuse is often quite transparent once investigated and starts with simply taking advantage of vulnerability, and abusing the powers conferred on deputies and attorneys rather than any more elaborate deception. -2- Most of the cases that attract media coverage are those where there has been a criminal prosecution. In this talk, however, I will consider the role of the Court of Protection, which operates within the framework of the civil law, and which has powers both to prevent abuse and to provide some redress for victims. THE COURT OF PROTECTION AND THE PUBLIC GUARDIAN The Court derives its powers from the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (“MCA”). Although it has no inherent jurisdiction, it has the same powers, rights, privileges and authority as the High Court (see s47 MCA), so it can make injunctions, including interim injunctions (see s48 MCA) which may protect a person who lacks capacity (“P”) from continuing financial abuse e.g. by freezing bank accounts or suspending the powers of officeholders. The Court has power to make decisions on behalf of adults who lack capacity to make the decision in question. All decisions made by the Court itself, or by any individual who is authorised to take a decision on behalf of an incapacitated adult, must be made in that individual’s best interests. The MCA does not define best interests. A best interest decision is a value judgment to be based on all the relevant circumstances in each case. However, s4 MCA does contain a statutory code of compliance for decision makers, providing a structure for the process of decision-making and highlighting some particular types of circumstances which are to be regarded as relevant. The Court has extensive powers in relation to property and affairs: see s16 and the specific dealings with property and affairs set out in s18(1), and can delegate these powers to a deputy or deputies who are appointed by the Court and who are ultimately accountable to the Court. Although s16(4)(a) provides that a decision of the Court is to be preferred to a decision of a deputy, this is obviously not a workable basis for day to day administration of an individual’s property and affairs, for which a deputy will always be appointed if there is a need for such administration to be dealt with and there is no attorney under a lasting or enduring power who can take on the task. The Court also has ultimate supervisory powers over attorneys appointed under a lasting power of attorney, either for personal welfare or property and affairs. -3- The Public Guardian is also a statutory figure (s57 MCA), Lasting Powers of Attorney, Enduring Powers of Attorney and Public Guardian Regulations 2007 SI 2007/1253 and has the following functions (s58(1) MCA): FUNCTIONS OF THE PUBLIC GUARDIAN (a) establishing and maintaining a register of lasting powers of attorney, (b) establishing and maintaining a register of orders appointing deputies, (c) supervising deputies appointed by the court, (d) directing a Court of Protection Visitor to visit— (i) a donee of a lasting power of attorney, (ii) a deputy appointed by the court, or (iii) the person granting the power of attorney or for whom the deputy is appointed (“P”), and to make a report to the Public Guardian on such matters as he may direct, (e) receiving security which the court requires a person to give for the discharge of his functions, (f) receiving reports from donees of lasting powers of attorney and deputies appointed by the court, (g) reporting to the court on such matters relating to proceedings under this Act as the court requires, (h) dealing with representations (including complaints) about the way in which a donee of a lasting power of attorney or a deputy appointed by the court is exercising his powers, (i) publishing, in any manner the Public Guardian thinks appropriate, any information he thinks appropriate about the discharge of his functions. -4- Appointment and supervision of deputies and of attorneys: key differences DEPUTY APPOINTED BY COURT OF PROTECTION Appointed by CofP Yes ATTORNEY(S) LASTING POWER OF ATTORNEY No – appointed by donor Conditions and restrictions Yes, if determined by Court on powers and set out in order made by Court on appointment or subsequently Yes, if included on form by donor and legally valid and consistent with operation of power of attorney Required to have security Yes, s19(9) MCA, generally, No bond in place for duration Court fixes level of security of appointment on appointment Limits on power to make Usually, mirroring statutory gifts to self or others from restrictions on attorneys’ P’s funds powers and set out in order made by Court on appointment Court may approve gift(s) retrospectively S12(2) MCA – of reasonable value, (a) to connected persons on customary occasions, (b) to charity Court may authorise gifts beyond scope of s12(2) Obliged to keep accounts Yes, s19(9)(b) MCA, 2007 No - but Court can direct and file reports with Regs production ad hoc – s23 MCA PG/Court Public Guardian has Yes – s58(1) MCA, 2007 No statutory duty to supervise Regs and can determine level of supervision Entitlement to/control of Yes – s19(7) MCA fees and remuneration Control – s23(3)(c) MCA Removal from office by Yes – s16(8) MCA – if not Yes – s22(4)(b)(MCA) Court acting in P’s best interests -5- SOME IMPORTANT RECENT PUBLISHED DECISIONS The Public Guardian and the Court have recently been active in bringing cases of financial abuse by deputies and attorneys to a determination, followed by publication of judgments which are highly instructive. Terminating the appointment of an attorney Re Harcourt – July 2012 The Court revoked the appointment of an attorney who had been obstructive in an investigation into her management of P’s property and affairs and who had not acted in her best interests. SJ Lush considered whether the revocation of an appointed attorney was an infringement of Article 8 of the ECHR (right to a private and family life) but held that was necessary and proportionate for the protection of Mrs Harcourt’s right to have her financial affairs managed competently, honestly and for her benefit and for the possible prevention of crime. Re Stapleton – July 2012 Mrs Stapleton executed an EPA appointing her son as her sole attorney with general authority to act on her behalf in relation to all her property and affairs. The local authority raised concerns with the OPG about the attorney’s conduct as care fees were outstanding and the attorney had sold the donor’s house (£188,000) and bought another property (£141,000) in his own name. He had also used his mother’s funds (£5,000) to purchase a pick-up vehicle which was registered in his sole name, and which he claimed was used to transport furniture and possessions between the two properties, as well as to take elderly relatives to visit his mother. The OPG applied to the Court of Protection for an order to revoke and cancel the registered EPA and to direct that a panel deputy be appointed. SJ Lush rejected the attorney’s attempt to explain these dealings with his mother’s property, holding that “this is not a case where there has been an inadvertent intermingling of funds. It is a wholesale assumption of dominion over Mrs Stapleton’s estate by her attorney, as if she were dead and he had come into his inheritance” The son was also ordered to pay his own costs of the application under r159 of the Court of Protection Rules 2007. -6- Dealing with misuse of investment powers/attorney acting in self-interest and not best interests of incapacitated person The Public Guardian v. C [2013] EWHC 2965 (COP) Miss Buckley was P’s niece, and acted as registered attorney under a property and affairs LPA. The Public Guardian applied for the revocation of the LPA and cancellation of its registration. Its investigation had shown that: Miss Buckley’s house had been sold for £279,000 some three months after the LPA had been registered The attorney had withdrawn £72,000 from the donor’s funds to set up a reptile breeding business - The attorney had used £7,650 of the donor’s capital for her own personal benefit Although the attorney said she visited Miss Buckley once a week, the nursing home said she had not visited at all until October 2012, when she appeared to have obtained Miss Buckley’s signature on some unknown documentation - At one stage there had been daily cash withdrawals of £300 from her account Miss Buckley’s estate may have incurred a total loss of approximately £150,000 The attorney attempted to argue that she had acted in her aunt’s best interests, but the court rejected this argument. The judgment of SJ Lush contains important guidance on the conduct and competence of attorneys, and emphasises that ignorance of the law is no excuse. “There are two common misconceptions when it comes to investments. The first is that attorneys acting under an LPA can do whatever they like with the donors’ funds. And the second is that attorneys can do whatever the donors could – or would – have done personally, if they had the capacity to manage their property and financial affairs . . . managing your own money is one thing. Managing someone else’s money is an entirely different matter. People who have the capacity to manage their own financial affairs are generally not accountable to anyone and do not need to keep accounts or records of their income and expenditure. They can do whatever they like with their money, and this includes doing nothing at all. They can stash their cash under the mattress, if they wish and, of course, they are entitled to make unwise decisions. None of these options are open to any attorney acting for an incapacitated donor, partly because of their fiduciary obligations and partly because an attorney is required to act in the donor’s best interests”. -7- Although the Trustee Act 2000 does not apply to attorneys, and there is no current guidance published by the Public Guardian, the judgment in Re Buckley suggests its own guidelines to be followed. “Until such time as the Office of the Public Guardian issues its own guidance to attorneys and deputies on the investment of funds, I would suggest that, as they have fiduciary obligations that are similar to those of trustees, attorneys should comply with the provisions of the Trustee Act as regards the standard investment criteria and the requirement to obtain and consider proper advice. I would also recommend that attorneys and their financial advisors have regard to the criteria that were historically approved by the court and the antecedents of the OPG in Investing for Patients, albeit with some allowance for updating” His suggested updating is shown in the table below: Investment Approximate Investment Code Value requirement Usual investment strategy ST1 £0-£85,000 Available quickly – Cash deposit that provides a safe competitive rate when compared with base rates and NS&I returns ST2 Over £85,000 All or part available quickly – very little risk acceptable Cash deposits with different financial institutions, including NS&I, which stay below the FSCS limits and/or a gilt portfolio to provide returns that compare favourably with base rates ST3 Cash with an existing portfolio Aim to make all or part available quickly – reducing risk commensurate with P’s requirements Depending on the nature of the portfolio, a liquidation process should be adopted using the annual CGT allowance. The cash funds should be retained in cash deposits with different financial institutions, including NS&I, which stay within the FSCS limits and/or a gilt portfolio to provide returns that compare favourably with base rates -8- He also emphasised three further points: (i) Attorneys should keep the donors’ money and property separate from their own or anyone else’s (paragraph 7.68 of the Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice). Where possible all investments should be made in the donors’ name but if for any reason that is not possible, the attorney should execute a declaration of trust or some other formal record acknowledging the donor’s beneficial interest in the asset. (ii) Subject to a sensible de minimis exception, where the potential infringement is so minor that it would be disproportionate to make a formal application to the court, an application must be made to the court for an order under section 23 of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 in any of the following cases: a) gifts that exceed the limited scope of the authority conferred on attorneys by section 12; b) loans to the attorney or to members of the attorney’s family; c) any investment in the attorney’s own business; d) sales or purchases at an undervalue; e) any other transactions in which there is a conflict between the interests of the donor and the interests of the attorney. (iii) Attorneys should be aware of the law regarding their role and responsibilities. Ignorance is no excuse. Attorneys should at least be familiar with the section on the LPA form headed “information you must read” and the provisions of the Code of Practice (section 42(4)(a) of the Mental Capacity Act requires an attorney acting under an LPA to have regard to the Code). Dealing with excessive gift-making and expenses claims by deputies (and attorneys) MJ and JM v. The Public Guardian [2013] EWHC 2966 (COP) MJ and JM were the niece and great-niece of P. They applied to the Court for retrospective approval of gifts and alleged deputyship expenses amounting to just under £300,000 from P’s funds of c.£500,000 to themselves, friends and charities GM was 92 at the date of the application. The applicants stated that they believed that leaving her with £200,000 assets was sufficient and that GM’s wishes were known to them, as they had known her all their lives. They said: “She was very fond of golden labradors, wildlife, the countryside, Codnor Castle, history, the environment, education, children, MJ and family and JM and family, and the Christadelphians. We have acted as we thought the C.O.P. order granted us, enabling us to gift and donate in relation to the size of the estate.” -9- These dispositions bore absolutely no relation to any which had been made by GM when she had capacity – her generosity towards the deputies had consisted of buying a meal or entrance fees on a joint outing, and the purchase of a fan heater for MJ’s daughter when she was at university. The deputies attempted to defend the dispositions on the basis that they did not intend to commit financial abuse, but believed that they were doing what GM herself would have wished to do. The court refused to accept this, referring to the applicants’ attitude as a “licence to loot”. The claim for expenses was rejected, the court holding that these were not the “reasonable expenses” to which deputies are entitled, but gifts disguised as expenses. As regards the gifts themselves, SJ Lush approved only the charitable gifts, and the individual gifts to the deputies limited to the applicable annual IHT exemptions for the relevant years, in addition to the gifts to the family of a friend of GM’s daughter. The total value of approved gifts was £73,352. SJ Lush revoked the appointment of the applicants as deputies, but made no final order for repayment of the unauthorised gifts and expenses, or for calling in the deputies’ security bond, as he described a statutory will under which they might nevertheless benefit as “the missing piece of the jigsaw” that awaited completion. SJ Lush also reviewed the law on authorised gifts by deputies and attorneys, and commented, as in The Public Guardian v. C that ignorance of the law is no excuse. In this case, the deputyship order, as is fairly standard, essentially followed the provisions of s12 MCA in relation to authorised gifts by attorneys (although it permitted reasonable gifts to individuals connected with GM, in addition to charities). SJ Lush also commented on the absence of published guidelines for gifts by attorneys and deputies, and reviewed the law in other comparable jurisdictions. He referred to his own decision in The Public Guardian v. C on the importance of applying for prospective authorisation of gifts above a “sensible de minimis exception”, and expanded on the meaning of this as follows: The following tax planning gifts would be regarded as de minimis: The annual IHT exemption of £3,000 and the annual small gifts exemption of £250 for up to 10 people, in the following circumstances Where P has a life expectancy of less than 5 years Where P’s estate exceeds the nil rate band for IHT The gifts are affordable having regard to P’s care costs and will not adversely affect P’s standard of care or quality of life There is no evidence that P would be opposed to gifts of this magnitude being made on his/her behalf - 10 - Public Guardian v. Lutz - Re Treadwell [2013] EWHC 2409 (COP) The Public Guardian applied to enforce a £200,000 security bond in respect of £59,375 unauthorised gifts made by Colin Lutz as property and affairs deputy for Joan Treadwell. Colin Lutz was her son from her first marriage. There were four other children of that marriage and Mrs Treadwell also had two step-children from her third marriage. Her third husband, Mr Treadwell, had been her attorney under a registered enduring power of attorney, although Colin Lutz had objected to its registration and had accused Mr Treadwell of financial impropriety once he had started to act under the EPA. Colin Lutz was appointed as deputy instead, and the order appointing him gave him the same powers in relation to gifts as an attorney would have had under s12 MCA. Colin Lutz applied for a statutory will departing from the provisions of his mother’s last capacitous will. The parties to the statutory will application reached a compromise, under which Mrs Treadwell’s step-daughters took her residuary estate in equal shares. After the statutory will was executed, Colin Lutz made extensive gifts to himself and members of his immediate family. SJ Lush considered the extent to which these gifts were within his authority or should be ratified, and identified the excess at £44,300 and ordered that the security bond should be enforced to that extent. He considered that Colin Lutz had resented the compromise of the statutory will application and subsequently sought to undermine it by dissipating any residuary estate his mother might leave on her death and diverting it into gifts to members of his own family. - 11 - Statutory will applications: the missing piece of the jigsaw ITW v. Z [2009] EWHC 2525 (COP) – “the Bad Samaritan” M was an elderly childless widow who wished to remain living in her lifelong home for as long as possible. She was befriended by a neighbour, Z, who persuaded her to come and live with him and be cared for by him and his wife. The local authority had concerns about Z and the adequacy of his care and commenced pre-MCA proceedings in the Family Division which culminated in M being removed from Z’s care into a local authority home. M had executed an enduring power of attorney in favour of Z, and he applied to register it. The local authority and the Official Solicitor objected to registration, and a professional deputy was appointed instead. There was evidence that Z had dealt with M’s property and affairs in ways which appeared to benefit him rather than her, and for which he refused to account properly to the court. The deputy was authorised by the Court of Protection to commence proceedings in the Chancery Division to recover some of M’s funds from Z. The professional deputy first brought an application for a statutory will. Z was the sole beneficiary of M’s last will, a will which appeared to be entirely valid. Z argued that he should likewise benefit under a statutory will. The Court refused to make an order in these terms (1) because there had been a fundamental change of circumstances since the date of the last will, in particular in that at that time M had envisaged she would live in Z’s care for the rest of her life, but in fact had only remained in his care for c.4 years and (2) because of Z’s previous dealings with M’s property and affairs. The Court took the view that as Z had already received large sums from M and was seeking further sums as an allowance for his care of her, he should be regarded as having had enough from M and not entitled to any more under a statutory will because either (a) he had had what he already had without impropriety but this was sufficiently generous or (b) he had had what he already had with impropriety, in which case there could be no possible justification for giving him anything more. Under s18(1)(k) MCA the Court has power to direct the conduct of legal proceedings in P’s name or on P’s behalf. This is an important power where, for example, P has made lifetime gifts of questionable validity and it appears that an undue influence claim might be successful in recovering the value of the gifts for P. In a case where the donee of the gift might argue that s/he was a person for whom P might be expected to provide (see CofPR 2007 r52(4)(e)) i.e. is a person who does not need permission to apply for a statutory gift or statutory will, the Court may be asked to decide the statutory gift or will application before considering authorising the litigation, as in ITW v. Z. - 12 - Re MR – 2008 – previous will of doubtful validity MR was an elderly woman who had never married or had children, and who appeared to be intestate, and had various extended family members with claims to be considered as beneficiaries of a statutory will as well as friends and carers who also had claims. One of her carers produced in evidence a relatively recent home-made will which benefited her and her son to the exclusion of any other potential beneficiary. The carer was crossexamined on the circumstances in which this document had come into existence. The evidence as a whole cast considerable doubt on the validity of the purported will. However, the Court of Protection has no jurisdiction to make any kind of ruling on the validity of any earlier will, which could only be determined in a contentious probate action. The Court dealt with the dubious document by holding that it was not a “relevant written statement” within the meaning of s4(6) MCA and by ordering the carer to pay her own costs of the application. In the light of the later observations in Treadwell about non-interference with succession rights and the judge’s view that there is “no written statement more relevant or more important than a will” this is the clearest possible indication of a past will being wholly discredited. The making of the statutory will had the effect both of ensuring that the validity of the doubtful document was never tested in a probate action and that the carer who attempted to rely on it received no benefit from MR’s succession. Compare NT v. FS [2013] EWHC 684 (COP) – weight to be given to an informal testamentary document from the distant past. Finally: a note of caution The Public Guardian’s activism in investigating potential financial abuse and bringing applications to the Court of Protection is a very important safeguard against financial abuse of adults who lack capacity. However, this does not mean that the Public Guardian will necessarily endorse or pursue to a fully contested application to Court every complaint that is brought to its attention. Where there is hostility between the complainant and the attorney or deputy, sometimes arising for reasons not directly connected to the conduct of the attorneyship or deputyship, the complainant may find it difficult to accept that the Public Guardian will not simply act as the complainant’s ‘voice’ in pursuing the complaint, but will take an independent view of the case. For example, I acted in a case where an IFA had been appointed as an attorney under an enduring power of attorney which contained provision for the IFA to charge for taking on the role. The donor’s adult children vigorously objected to these (substantial) charges and persuaded the OPG to investigate. The investigation concluded that there were insufficient grounds for the Public Guardian to apply for the revocation of the EPA, and led to the attorney raising further charges in responding to the investigation, which ultimately had to be determined by the Court under paragraph 16 of Schedule 4 MCA, all ultimately involving some potentially irrecoverable costs to the donor’s estate. - 13 - CONCLUSIONS RISK MANAGEMENT Exercise care in the selection and appointment of office-holders: particularly inappropriate to have non-professional deputy acting where large personal injuries settlement to manage. Consider restrictions or conditions in order to minimise the risk of abuse by an attorney e.g. a supervisory condition for the attorney to financial records or accounts to someone who is independent, or a requirement that the attorney seeks independent financial advice. But note that a restriction which effectively requires arbitration of attorneyship issues by a third party e.g. a provision which requires an accountant or solicitor to adjudicate over the donor’s business affairs, or a provision which requires all of the donor’s children to agree to decisions, when not all have been appointed attorneys, will be severed as a restriction fettering the attorney’s authority. Ministry of Justice website publishes decisions of the Court of Protection on severance of restrictions which are invalid or incompatible with the provisions of an LPA. http://www.justice.gov.uk/protecting-the-vulnerable/mental-capacity-act/orders-madeby-the-court-of-protection/lasting-powers-of-attorney Ensure office-holders are aware of their duties and obligations, including in relation to investments and gifts. DETECTING FINANCIAL ABUSE Observe lack of available funds to meet vulnerable person’s outgoings e.g. care home fees, where arrears may prompt investigation. Investment advisers, intermediaries and bank staff may be aware of changes/realisations of investments which may not have been properly authorised/in owner’s interests. If social services are involved, they may observe suspicious conduct. Observe marked increases in assets or disposable income of carer or office-holder. DEALING WITH THE PUBLIC GUARDIAN AND THE COURT Seek involvement of Public Guardian where abuse suggested Consider applications for interim injunctions/order for reports/repayment of excessive gifts/applications for removal of office-holders/default payment out of security bond/statutory wills and gifts - 14 -

![Parent or Guardian Notification of a Resolution Session [SELPA17]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007848399_2-2ddadc03374b5cdf4e09c64183bc7dce-300x300.png)