Chemical Warfare

advertisement

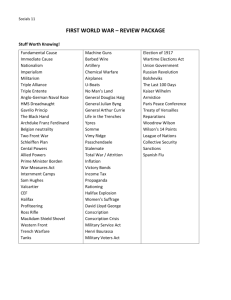

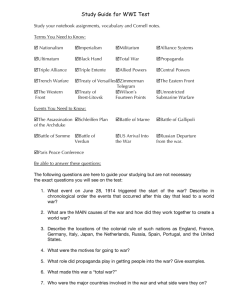

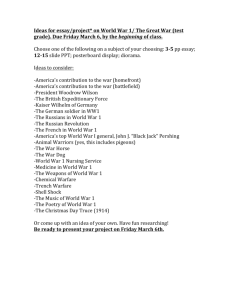

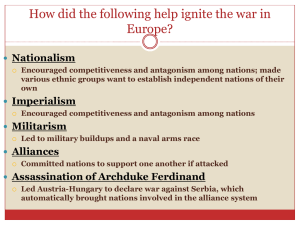

Chemical Warfare in World War I: A Multi-genre Analysis California State University Dominguez Hills December 11, 2010 English 350: Advanced Composition Dr. Cauthen Table of Contents FAQ…………………………………………...1 Rhetorical Analysis……………………………2 Newspaper Article…………………………….3 Soldiers Diary…………………………………4 Help Wanted Advertisement………………….5 Textbook Section……………………………...6 Death Notification Letter……………………...7 Introduction of Chemical Warfare FAQ Introduction of Chemical Warfare When was poison gas introduced as a weapon? Poison gas was introduced during World War I on April 19, 1915 at the First Battle of Ypres near Belgium. Who introduced poison gas as a weapon? Germany was the first country to utilize chemical weapons successfully. It is hard to believe it has been nearly ninety-five years since the German’s deployed gas at the Battle of Ypres, and yet even today, the thought of chemical weapons still strikes fear in the heart of combatants and civilians alike. How was poison gas first deployed? Chlorine cylinders were first utilized to administer the poison gas on the battlefield. “As the development stages of chemical warfare progressed so did the technology and in 1914 German physicist’s Fritz Haber suggested the idea that chlorine gas be discharged from cylinders.”1 Following the First Battle of Ypres were the Allies prepared to retaliate with chemical weapons? No, “the British had limited scientific knowledge as well as resources to produce chemical agents, only one firm in the country, the Castner-Kellner Alkali Company, could expand its output of liquid chlorine to produce bulk supplies.”2 When did the Allies officially introduce chemical weapons? By September, a group of Royal Engineers, advised by prominent scientist had accumulated a sufficient amount cylinders filled with chlorine gas. Thus, the British first used poison gas at the Battle of Loos in September 1915.3 However, Frances efforts at retaliation was hindered by the weak state of their chemical industry, “which could produce little chlorine and thus forced French military scientists to consider other alternatives, including a very early move toward toxic gas shells.”4 As for the United States, they did not actively pursue the development of chemical weapons until after they entered the war in 1917. As the title suggests, Charles Heller’s Chemical Warfare in World War I: The American Experience 1917-1918 analyzes the American combatants experience with chemical warfare in World War I. Even though Heller’s work was published three years before Fritz Haber’s The Poisonous Cloud, Haber’s is still considered the scholarly standard for the study of the introduction, development, and organization of chemical warfare. This is due to the fact that the Americans did not play a very significant role in the development and organization of chemical warfare, simply because they did not enter the war until 1917. As a result Heller’s analysis of the introduction, development, and organization of chemical warfare fails to examine many of the crucial elements of the historiography of chemical warfare, which occurred prior to the Americans involvement in World War I. Furthermore, once the United States became involved in World War I “President Wilson's efforts to maintain strict neutrality during the first two years of the war hampered the Army's planning for defense”5 and as a result the United States “preparations for chemical warfare lacked a sense of urgency.”6 Heller explains, “the same day war was declared, the Council of National Defense formed a Committee on Noxious Gases.”7 Heller’s criticism that the United States was not prepared for chemical warfare coincides with Haber’s argument that “several branches of the war department had been involved and had proceeded independently so that there had been much conflict, many delays, and a few links with research and development.”8 As a result, Heller suggests, “ignorance, shortsightedness, and unpreparedness extracted a high toll at the front, a toll that the United States with its intellectual and technological resources should not have had to pay.”9 Heller’s work has contributed significantly to the historiography of chemical warfare by providing much needed insight into the limited scholarship regarding the American’s experience of chemical warfare during World War I. German’s Advance at Ypres Introduce Poison Gas! QuickTime™ and a decompressor are needed to see this picture. German forces break through allied lines as harsh fighting continues outside of Ypres, Belgium Ypres, Belgium April 20 – “Heavy fighting has been in progress on the British front in Belgium, where the Germans attacked at four points around Ypres”10. German forces pushed back Britain’s 1st infantry battalion in the North using poison gas to deter Allied forces. The fighting escalated yesterday around Noon as German artillery forces bombarded French troops near the town of Ypres, destroying a landscape that just days earlier was picturesque European countryside. Prior to the German attack, not much was known of the effects of asphyxiating gas. According to a field report, “The bomb, which is about the size of a football, explodes and fills the air with a dense yellow smoke.”11 The effects of the poisonous gas administered by German forces causes the victim to choke and become disoriented on the field of battle, which proved to be extremely effective in suppressing the French troops. Today, I headed to the field hospital as I wanted to see the effects of this new weapon for myself. “I witnessed French troops come into the base hospital who were still suffering from the effects of the gas they inhaled yesterday at Ypres.”12 In a telegram sent to the war department, The Earl of Ypres Sir John French suggests “The quantity produced indicates a long and deliberate preparation for the employment of devices contrary to the terms of the Hague Convention, to which the enemy subscribed. The false statement made by the Germans a week ago, to the effect that we were using such gases, is now explained. It was obviously an effort to diminish neutral criticism in advance.”13 Thus, if preventive measures are not taken to counteract the use of poisonous gas on the battlefield the cause-and-effect relationship of a very sudden and extremely complex technological innovation” and it’s effects on the combatants will prove to be crucially important in determining the outcome of this war. There is no cause greater than this war; Allied forces are already at a disadvantage when it comes to the research and development of Chemical warfare. Since Germany was the first to successfully introduce chemical weapons on the battlefield, they do not have to worry about temporary solutions to the defense of gas. - September 21Arrived in Loos this morning, a small rural town in the French countryside. The town is quiet and I imagine would be beautiful if it were not in the middle of a war. We are being told to keep watch day and night as the Germans are said to be close. - September 22Woke up this morning to a beautiful clear day, it seemed as if I could see for miles in any direction and still no sign of the Germans. My regiment had been ordered to cooperate in a “subsidiary operation in which we will fight around the Northern outskirts of Loos on the left og the French attack on Artois.”14 I have night watch tonight, rumor has it that if we encounter the Germans anytime soon we will deploy small cylinders filled with poison gas. - September 23 Today has been extremely cold. I have ever been this cold before. Camp is as busy as ever a report from command said that my infantry division is to be an instrumental part of the “biggest Anglo-French offensive of the war to date.” 15 If intelligence is correct, the offensive should begin in a few days. - September 24 Rain continues to pour down from the heavens, I am beginning to think GOD does not want us hear. Despite the rain we drilled for several hours this afternoon. The state of the men is getting more miserable as the days go by. -September 25– German howitzers have been bombarding our position since sunrise, tearing the landscape all around us to pieces. There is a sense among the men that this is the beginning of something big, it seems like this encounter with the German’s could be a major turning point in the war. - September 26The battle continues to rage, I have been stuck in the trenches all night, the pounding of the howitzers reminds me of a twisted nursery rhyme. I witnessed a burst of dense yellow smoke near the advancing German lines; it looks as if we have finally introduced chemical warfare. - September 27 It is hard to determine if the use of poison gas had been a success, early field reports suggest that we have suffered just over 50,000 casualties, and over 2,600 gas related casualties.”16 It seems to me that the casualty numbers are too high to suggest that our first attempt at chemical warfare was a success, but rather it was a failure. ATTENTION: Scientists Needed The British Army is in urgent need for academic scientists who specialize in chemical research and development. Are you familiar with the systematic organization of laboratory research? Do you thrive under pressure? Do you want to help your countries war effort? Then apply today! Report to the headquarters of your Majesties Army located in London, England. The development of anti-gas defense systems occurred differently in Germany, Britain, and France. Moreover, most historians argue that between the three, the latter was by far the least successful of the group. “The Germans made much faster progress with their mask because they were not distracted by interim solutions.”17 Thus, the Allies’ initial retaliation effort was hindered by the British lack of chemical resources, to retaliate using the same technology and brutality as the Germans had wielded at Ypres was seen as no easy task. In fact, many scholars suggest “ links with manufactures had to be strengthened; and, some coordinating body of makers and users with a leavening of academic chemists was urgently required to develop the entire chemical warfare effort.”18After nearly three months of development, the British retaliated at the battle of Loos using 168 cylinders of chlorine gas. “Britain’s first attempt at a large-scale gas cloud discharge at Loos is seen universally by historians as a failure.”19 Nevertheless, both British and German forces pursued the development of defenses with more intensity following the battle of Loos20. QuickTime™ and a decompressor are needed to see this picture. Department of the Royal Army Headquarters, British Army European Command, Buckingham Palace, London SW1A 1A Mr. and Mrs. Erickson 19 Sutherland Street LONDON EC1Y 8SY UNITED KINGDOM Mr. and Mrs. Erickson It is with deep regret to inform you your son, Lance Corporal Ralph Erickson 1st Infantry of the Royal Army died 24 October 1914 in action at the battle of Ypres near Belgium. The nature of your sons death is not entirely clear, however it is thought that he may have been a victim of German poison gas which was administered by Germany in direct violation of the Hague convention at the Battle of Ypres. Your son’s death will not go in vain as “the countless cruel technological innovations in weaponry of humankind, such as poison gas have come to be stigmatized as morally illegitimate”21 by the Allied forces. By the end of this war we will do everything in our power to outlaw the use of chemical weapons as a form of modern warfare. It is great sorrow that I have to deliver this news to you, as I know it brings much grief into your families lives. Understand this, your son performed his duty and service to his country honorably as he was instrumental in the allied victory at Ypres. “I sincerely hope the knowledge that Ralph was an exemplary soldier and died while serving his country will comfort you in this hour of great sorrow.”22 1 Ludwig Fritz Haber, The Poisonous Cloud: Chemical Warfare in the First World War (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986), 27 2 Edward M. Spiers, Chemical Warfare (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 19. 3 Johnson, John A. "Chemical Warfare in the Great War." Diss. Villanova University, 1990, 94. Johnson, 98 5 Charles Heller, “Chemical Warfare in World War I: The American Experience, 1917-1918” (September 1984) http://www-cgsc.army.mil/carl/resources/csi/Heller/HELLER.asp (accessed 11 December 2010). 4 6 Heller. Heller. 8 Haber, 143 9 Heller. 10 "The Germans Pierce British Lines." New York Times 21 Apr. 1916. Print. 11 "Ypres Lines Hold Fast." New York Times 27 Apr. 1915. Print. 12 Ibid. 13 Horne, Charles F. "First World War.com - Primary Documents - Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett on the Battle of Sari Bair, 6 August 1915." First World War.com - A Multimedia History of World War One. 22 Aug. 2009. Web. 11 Dec. 2010. <http://www.firstworldwar.com/source/saribair_bartlett.htm>. 14 Lloyd, Nick. "Lord Kitchener and ‘the Russian News’: Reconsidering the Origins of the Battle of Loos." Academic Search Premier. Web. 10 Dec. 2010. 15 Lloyd, 346 16 Donald Richter, Chemical Soldiers: British Gas Warfare in World War I (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1992), 86 17 Haber, 71 18 Haber, 52 19 Haber, 55 7 20 Haber, 57 Richard M. Price, The Chemical Weapons Taboo (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1997), 1 22 U.S. Army. "Death Notification." Letter to Mr. and Mrs. Fowlke. 14 Mar. 1968. MS. 21