ABC Coursework with introduction

advertisement

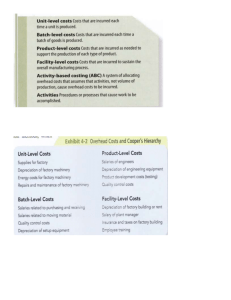

In the past few years we have seen the dramatically growing importance of high quality information for management decision-making. One of the most important areas of financial management is that of cost management systems, used for costing and budgeting. In the face of growing competition due to the rise of globalisation, companies now need the information about the profitability of a product, customers or markets, about the costs consumed by differing activities and other areas where costs play an important role. If a firm is to keep up with its strongest competitors, its costing system has to implement the ability to react to changes in product and activities structure and show these changes in their product costing. If the costing system does not change and the process, activities and product structures do not conform with the industry dynamics, then the firm's costing system will become obsolete and incorrect and distorted product costing will be produced. Traditional costing systems, dating from the 1800s are based on volume-based allocation of overheard. These systems have lost relevance in a manufacturing environment that has seen a sharp increase in overhead and a subsequent decline in direct labour. The traditional costing systems tend to distort product costs and lead to poor strategic decision-making. One innovative costing method, Activity-Based costing, has become the accepted remedy for the limitations of the traditional cost accounting systems. Instead of the arbitrary allocations which are at the heart of the conventional methods, ABC assigns costs to products and processes by computations intended to approximate cause-andeffect relationships in the production processes. As Sohal and Chung (1998) explain, managers and accountants have become dissatisfied with the traditional costing systems with concerns about their suitability in the modern manufacturing environment. As Cooper and Kaplan (1998) state, the traditional system was satisfactory decades ago when firms only had a narrow range of products, and the most important production factors were the cost of direct labour and materials which are easily traceable to the individual products. Overheads were not a big proportion of total costs (Ballakur 1991). This made it difficult to justify the more sophisticated allocation methods which are significantly more expensive to implement and operate. In today’s environment, using traditional methods is not suitable as absorption rates based on ‘simple’ activity measures is not fully representative of complex relationships between support activities and outputs ( Allan, 1998, p.161). The cost structure of products has changed, ‘increasingly enriched with technology and overhead’ (Ballakur, 1991). Direct labour is now only a small part of costs to corporations while the costs for overhead functions such as factory support operations, marketing distribution and engineering have become extremely prominent for a firm (Cooper and Kaplan, 1988). As Eddy (2004) and Cokins (1998) reported, companies that use the traditional indirect cost allocations may actually lose money on certain products and customers by underestimating their costs even if their accounting systems may be reporting them as profitable. This can have unintended negative strategic and operational consequences for the firm. To assign organisational expenses to products the traditional systems use volume driven allocation bases. However, in today’s environment a lot of resource demand is not driven by or proportional to the number of units produced or sold, but more so by the number of batches or production runs that are undertaken. Because of this it is criticised for not actually measuring the cost of resources used to design products and to sell and deliver to consumers accurately (Cooper and Kaplan, 1992 p.1). Ballakur (1991) argues that traditional systems are not found to be an adequate way to manage costs and shift resources in order to increase revenue. The manager does not get a clear picture of how much the activities that are done in the organisation cost. The system only tells how much of these expenses went into each individual resource. Traditional cost systems in fact often understate profits on the high volume products whilst overstate the profits for speciality, low volume items when the cost of nonvolume based activities is relevant to the product. Using an absorption costing system requires a ‘subjective selection of absorption criteria, allocation criteria and volume assumptions’ (Geri and Romen, 2005). This can lead to traditional techniques providing misleading information. Cooper and Kaplan (1998,p.100) found that calculating the actual demand a product makes on resources of the organisation can be as wrong by as much as 200%. Three case studies are presented by Innes and Mitchell (1990), which were undertaken on firms who had implemented and organised ABC systems by CIMA. These found that gearing traditional costing towards short run decision analysis gives managers of organisation’s high potential for gathering misleading information (Sohal and Chung, 1998, p.146). Drury (2006) agrees with this high potential possibility as the system relies heavily on arbitrary allocation bases of indirect costs. It is almost impossible to end up with accurate product costing figures whilst using the traditional techniques, as well as being inadequate to provide other information which could be used in performance management. The absorption costing system was designed to make sure that all product costs are covered, but not to make sure that these product costs are accurate (Chadwick and Magin, 1989, p.65). So much so that manufacturing costs that are not even caused by the individual product are assigned to those products. For example Willie et al (2006, p. 299) looked at a case where a security guard’s salary was allocated to all products even though it was not at all affected by the by the volume of products made and sold in that period. Turney (2008) explains how interest in ABC was increased by emerging evidence of the financial benefits, along with improvements in technology, such as the use of Internet, ‘Business Intelligence systems’ to report ABC information, new ABC methods and software. This was along with the increased opportunity cost of having inaccurate product costing and information processing costs no longer being too high, and acting as a barrier to entry (Holzer and Norreklit, 1991). There was a change in the manufacturing environment that traditional systems could not keep pace with; product life cycles were continually shortening and the direct labour component as a percentage of total overhead was rapidly declining (Ballakur, 1991). Having been designed decades ago, traditional techniques were now very much out of touch. Organisations began to be more complicated, with indirect and overhead costs growing at a speedier rate than sales or services. This ‘displaced the costs of the frontline worker’ (Cokins, 1998). ABC has reduced the ambiguity which surrounds cost estimation. This makes it a very valuable tool when using it to support strategic decision-making. ABC costing systems solve the problems found with the outdated traditional techniques. It corrects these limitations by identifying all the activities and the costs that go into producing and distributing a product, performing a service or a process. ABC improves upon the traditional approach by using a two-stage allocation procedure and multiple cost drivers. In the first stage, significant activities are identified and overhead costs are assigned to each activity in proportion to the resources used. The focus on resource consumption means that this new costing system will support strategic decisions of the firm (Cooper 1990 as cited in Geri and Romen, 2005). Cost drivers are then identified for each of these cost pools. This allows the links between the activities and the resource demands that these activities make in order to give managers a clear view of the way revenues are generated and resources consumed. In stage two, the overhead is allocated from the cost pull to the final outputs, or cost objects, in proportion to the amount of the cost driver consumed. These many cost drivers, unlike the method in traditional systems where overheads are pooled by departments, are representative of diverse factors of cost drivers more accurately when products are costed. (Willie et al, 1996, p.299). In traditional costing systems, the only costs that can be traced directly back to the product are direct labour and material (Akyol et al, 2005). In ABC, with multiple cost drivers, this is not the case; activities can be categorised as either value-adding or non-value-adding activities, with those that do not add anything able to be eliminated. Cooper et al (1992) recognised that some firms found it beneficial to the firm to rank all activities used in the ABC system according to the value they give to the customer. There could, however be negative implications to this in that a full blown analysis would have to be done to rank these, which would be costly to the firm. ABC aids decision-making by becoming a key management tool for planning; it calculates the difference between the demand and the supply for the product which allows expected future spending on resources to be predicted. ABC greatly reduces any uncertainty by making the cost accounting system of firms interactive (Feldman and March, 1981). In their three case studies, Innes and Mitchell (1990) recognised potential benefits of the implementation of ABC in a relatively short period of time. These included more accurate product line costs, which were extremely beneficial for firms with cost sensitive prices and where promotion strategies and decisions on the range and mix of the products need to be made regularly (Sohal and Chung, 1998, p. 141). These accurate product line costs mean that all future costs will be predicted on the accurate historic costs which reduces greatly the potential for misleading information. With this more accurate information, managers can more clearly see cost variability and clearly see ways in which they can reduce the demands the activities make on the organisation's resources. This may lead to increase profits, from the ability to lower costs or increase throughput ( Cooper and Kaplan, 1991) Activity-Based Costing systems, following a great success, began to be appreciated as a strong tool for profit analysis (Turney, 2008, p.1). This would be due to the fact that ABC techniques could disclose hidden costs and sources of profitability that are not easily visible. ABC allows firms to focus on the profitable markets and customers only, getting rid of any unprofitable products, activities the firm is doing that does not add value and finally lower costs of the production process by altering products. It also allows management to partake in pricing strategies and reprice products if need be. Ittner (1999) confirms this view by stating that it can be a 'powerful means of quantifying the financial impact of poor quality'; this allows the firm to be much more specific and target the individual activities and processes that are causing the lag, to either improve them or get rid of them completely. ABC allows a stronger differentiation of prices among products, customers and the market as a whole. (Cooper, 1988, Kaplan and Atkinson, 1998 and Goebel 1998 as cited in Eddy et al, 2004) ABC is by no means just a cost accounting tool. Turney (2008) describes it as ' the emerging foundation of performance management'. Sohal and Chung (1998, p. 143) found in the two case studies they carried out that ABC delivers many benefits to the firm. It gives the company a greater position competitively in the market; this is done by the more accurate information available on costing and pricing. This cost accounting technique also creates suitable benchmarks, which allows managers of a firm to make comparisons in relation to imported competitive goods. Other ways in which benefits are delivered to the firm is that it allows to outsource current in-house inefficient products, better weighting analysis which allows more competitive capital investment, and development of performance measurements which validates annual expenses in annual budgets. The fact that is provides a strong reliable inclination of what long run variable costs will be is a strong strategic tool for the managers of the firm. Despite the many advantages of ABC systems, it is not without its faults. As Piper and Walley (1991) correctly stated, 'ABC creates a more complicated costing system, but not necessarily an accurate or useful one'. One area in which many theorists argue the strength of ABC is that in decision-making. Even though it aids in this, it cannot solely be relied upon to be an adequate measure on its own. Geri and Romen (2005) have argued that when the volume of production alters ABC is unable to predict profits and thus cannot be relied upon as a sole tool for decision-making. Turney (2008, p.5) also agrees with the statement; in that with ABC you could not reliably measure what the short term impact of decisions would be on operating costs, along with inventory and throughput. Because of this we could argue that even though ABC has its advantages in providing accurate product costs, additional information is needed for analysis which requires extra effort and expense. One way in that ABC does not improve on the traditional techniques is that of arbitrary cost allocation. Both are based on these subjective allocation methods. The only difference between the two really is the number of allocation or cost drivers. The fact that they are both subjective methods means that both methods may cause for misleading decisionmaking. Another negative aspect of ABC is that of the relationship between the activities and resource consumption. Not only is it difficult to link the cost drivers to the individual product in the initial implementation of the system, it also regards the relationship between the resource consumption and activities as 'linear, absolute and certain' (Geri and Romen, 2005). This leads us to the conclusion that if there are an increase in the number of activities there will be an increase in the costs and visa versa. We know for a fact, however, that there are many discontinuities in costs, meaning we should not rely on ABC. The Gartner Group estimated that only between 20% to 50% of global one thousand firms have adopted ABC (Turney, 2008, p.7) One of the main reasons for this is the cost of implementing and maintaining the activity-based costing system. It requires change to the organisational structure as a whole. Babad and Balachandran (1993, p.565) recognise that looking at the activities in extremely intricate detail is not only costly to collect, store and process, but allows for error to be found in the data in the collection, reporting and estimation of sources, which allows for inconsistencies between different cost drivers for different systems and allows errors in pricing and costing of the products. The more complex analysis described that is required for ABC could mean that the costs outweigh the benefits if the costs for gathering and updating information is too high.