“Somalia: From Collapsed State to Paper State - Somali - JNA

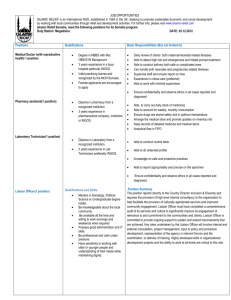

advertisement