Answers to Questions in Economics for Business

advertisement

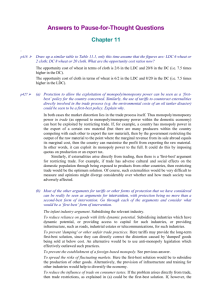

Answers to Pause-for-Thought Questions Part I: Business in the International Environment Chapter 23 Given the diverse nature of multinational business, how useful is the definition given for describing a multinational company? As a basic definition it is adequate. A more complete definition, however, would need to take account of some of the other dimensions of multinational organisation and practice. Ultimately the degree of ‘multinationalism’ of every business needs to be considered on a business-by-business basis. Before reading on, try to identify other ways in which locating production overseas might help reduce costs. By locating production overseas a business may be able to: reduce transport costs by locating nearer to markets or to sources of raw materials or other inputs; avoid paying tariffs by locating production in the same country as the market and hence avoiding importing the product from abroad; attract government support, such as subsidies or favourable tax breaks, thus reducing both the costs of production and the risk of the investment. Why might the size of these regional ‘knock-on effects’ of inward investment be difficult to estimate? Regional knock-on effects are difficult to estimate as the jobs created are not a direct consequence of the inward investment. For example, regional suppliers to a new business may or may not increase their workforce to meet the increased demand for their product. They may, for example, be able to improve their productivity, which might have a minimal effect on new job creation. What problems is a developing country likely to experience if it adopts a policy of restricting, or even preventing, access to its markets by multinational business? If rival countries have a more open attitude towards multinational investment, they are more likely to receive such investment, whereas a country that tries to restrict or control such investment is likely to be overlooked when multinational corporations are looking to expand. Given the shortage of domestic finance for investment, the cost for the developing country is likely to be a lower rate of economic growth and employment generation. Chapter 24 Draw up a similar table to Table 24.1, only this time assume that the figures are LDC 6 wheat or 2 cloth; DC 8 wheat or 20 cloth. What are the opportunity cost ratios now? The opportunity cost of wheat in terms of cloth is 2/6 in the LDC and 20/8 in the DC (i.e. 7.5 times higher in the DC). The opportunity cost of cloth in terms of wheat is 6/2 in the LDC and 8/20 in the DC (i.e. 7.5 times higher in the LDC). Answers to pause-for-thought questions in Economics for Business (3rd edition), John Sloman and Mark Sutcliffe Show how each country could gain from trade if the LDC could produce (before trade) 3 wheat for 1 cloth and the developed country could produce (before trade) 2 wheat for 5 cloth, and if the exchange ratio (with trade) was 1 wheat for 2 cloth. Would they both still gain if the exchange ratio was (a) 1 wheat for 1 cloth; (b) 1 wheat for 3 cloth? The LDC still gains by exporting wheat and importing cloth. At an exchange ratio of 1:2, it now only has to give up 1 kilo of wheat to obtain 2 metres of cloth, whereas without trade it would have to give up 3 kilos of wheat to obtain just 1 metre of cloth. The developed country still gains by importing wheat and exporting cloth. At an exchange ratio of 1:2, it can now import 1 kilo of wheat for only 2 metres of cloth, whereas without trade it would have to give up 5 metres of cloth for 2 of wheat (i.e. 2½ of cloth for 1 of wheat). (a) Yes. (This ratio is between their two pre-trade ratios.) (b) No. The LDC would gain, but the DC would lose. It would now have to give 3 metres of cloth for 1 kilo of wheat, whereas before trade it only had to give 2½ metres of cloth for 1 kilo of wheat. Thus the developed country would choose not to trade at this ratio. (a) Protection to allow the exploitation of monopoly/monopsony power can be seen as a ‘first-best’ policy for the country concerned. Similarly, the use of tariffs to counteract externalities directly involved in the trade process (e.g. the environmental costs of an oil tanker disaster) could be seen to be a first-best policy. Explain why. (b) Most of the other arguments for tariffs or other forms of protection that we have considered can really be seen as arguments for intervention, with protection being no more than a second-best form of intervention. Go through each of the arguments and consider what would be a ‘first-best’ form of intervention. (a) In both cases the market distortion lies in the trade process itself. Thus monopoly/monopsony power in trade (as opposed to monopoly/monopsony power within the domestic economy) can best be exploited by restricting trade. If, for example, a country has monopoly power in the export of a certain raw material (but there are many producers within the country competing with each other to export the raw material), then by the government restricting the output of the raw material to the point where the marginal revenue from its sale abroad equals its marginal cost, then the country can maximise the profit from exporting the raw material. In other words, it can exploit its monopoly power to the full. It could do this by imposing quotas on production or an export tax. Similarly, if externalities arise directly from trading, then there is a 'first-best' argument for restricting trade. For example, if trade has adverse cultural and social effects on the domestic population through being exposed to products from other countries, then restricting trade would be the optimum solution. Of course, such externalities would be very difficult to measure and opinions might diverge considerably over whether and how much society was adversely affected. (b) The infant industry argument. Subsidising the relevant industry. To reduce reliance on goods with little dynamic potential. Subsidising industries which have dynamic potential, or providing access to capital for such industries, or providing infrastructure, such as roads, industrial estates or telecommunications, for such industries. To prevent 'dumping' or other unfair trade practices. Here tariffs may provide the long-term first-best solution, since they can directly correct the distortion caused by 'dumped' goods being sold at below cost. An alternative would be to use anti-monopoly legislation which effectively outlawed such practices. To prevent the establishment of a foreign-based monopoly. See previous answer. To spread the risks of fluctuating markets. Here the first-best solution would be to subsidise the production of other goods. Alternatively, the provision of infrastructure and training for other industries would help to diversify the economy. 2 Answers to pause-for-thought questions in Economics for Business (3rd edition), John Sloman and Mark Sutcliffe To reduce the influence of trade on consumer tastes. If the problem arises directly from trade, then trade restrictions, as explained in (a) could be the first-best solution. If, however, the products could equally well be produced by multinationals within the country, then a tax on such goods, or even banning them, would be the first-best solution. To prevent the importation of harmful goods. See previous answer. To take account of externalities. Unless the externalities arise directly from the trade process (as explained in (a)), the first-best solution would be to tax products or processes that produce external costs and subsidise those that produce external benefits. The exploitation of monopoly power. As explained in (a), trade restrictions are a first-best solution for the country imposing them. The first-best solution for the world, however, would be to attempt to reduce that monopoly power by encouraging freer trade and more competition. To protect declining industries. The first-best solution would be to subsidise such industries directly – at least for a short time while they gradually run down. If the problem is simply one of employment in the areas where those industries are located, then providing training or other forms of help to those likely to be made redundant, or improved infrastructure to encourage the development of new industries in those areas, might be the optimal solution. Non-economic arguments. What is first best in each case depends on what the objectives of intervention are. The efficient solution in each case is to target intervention as closely as possible at the problem so as to avoid side-effects from the intervention. Thus, if the objective is to protect traditional rural ways of life, then trade restrictions or export subsidies for agricultural products may be a very blunt instrument. It would be better to target support directly on the communities affected, for example, by providing support for the development of rural cottage industries. Chapter 25 Is joining a customs union more likely to lead to trade creation or trade diversion in each of the following cases? (a) The union has a very high external tariff. (b) Cost differences are very great between the country and members of the union. (a) Trade diversion. It may now be cheaper to buy a good from a high-cost producer within the union rather than from a lower-cost producer outside the union. The reason is that the high tariff would have to be paid on such imports, making their price higher than the high-cost goods produced inside the union. (b) Trade creation. If the country joining the union has significant cost differences from existing members, then this is likely to create trade from the high to the low cost country. Does the adoption of a law enforcing improved working conditions necessarily lead to higher costs per unit of output? Higher costs do not necessarily follow from improving working conditions. Better conditions may increase worker productivity as workers feel motivated and/or able to work harder or more effectively. Even laws to increase the statutory minimum holiday entitlement or reduce the maximum working week could boost output if workers felt motivated to work harder and managers were stimulated to increase the organisation’s efficiency. 3 Answers to pause-for-thought questions in Economics for Business (3rd edition), John Sloman and Mark Sutcliffe Why may the new members of the EU have the most to gain from the single market, but also the most to lose? Because their economies are less harmonised with the other member economies, and because there are more internal barriers, partly as a result of transitional arrangements. There is more chance, therefore, of both trade creation and trade diversion. Also there is likely to be more change in their economies. The more change there is, the more will there be gainers and losers (new industries growing up, and old industries declining, with a resulting loss of jobs). 4