Potluck Schools - Youth Initiative High School

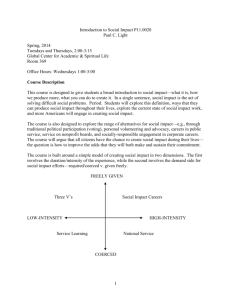

advertisement