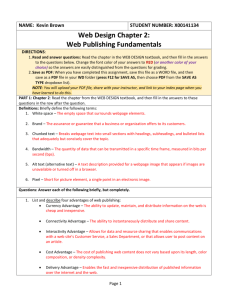

article - 'Beyond The Doodle'

advertisement

Doodling is an informal and absent-minded mode of mark-making that occupies pockets of time and space in meetings or during phone conversations, is engaged in by many people who would never consider themselves artists, and because of its unconsidered character is thought to reveal the unconscious pre-occupations of its creator. The doodle is now so familiar that it seems to be a natural given; yet the term, and the concept behind it, is a comparatively recent invention, dating from the late 1920s and becoming something of a cult in the mid 1930s, when books like ‘Everybody’s Pixillated’ (Arundel 1937) were an indication of its popularity. Despite the fact that there seems to have been a recent revival of interest in the genre, no-one has looked at the cultural background to this phenomenon, beyond its immediate history (eg Presidential Doodles, Greenberg 2006), and this is what I want to do here. Right from the start, the doodle combined several contradictory features: it was supposedly a universal, democratic form of drawing, yet celebrity doodles by film stars, politicians and businessmen are the focus of Arundel’s book; it is an amateur activity, yet there are clearly leakages between it and the world of Fine Art; it was read as an individual signature, yet at the same time was analysed in terms of impersonal processes; it was allegedly unconscious, yet signs of intermittent conscious interference are present in many doodles; and finally, the interpretative strategies brought to bear on doodles were hybrid- part graphological, part Freudian symbolism and part gestural. I want to suggest that there are multiple leakages both ways between the private and slightly shameful activity of doodling and some of the more brazen experiments and challenges of Modernism. If Dadaism, for example, asserted that the creation of a work of art was a private affair, having little to do with responsibility or the need to communicate; if early forms of abstraction, such as Kandinsky’s, justified themselves in terms of ‘inner necessity’ and appealed to the innate psychological significance of forms and colours, these can be seen as helping to prepare the ground that the doodle would soon occupy. Conversely, doodles, like the child art contemporary with them, provided a rich source of inspiration for artists such as Klee or Miro, as well as more recent artists such as Cy Twombly. Typically, in this respect Outsider Art, whose creators often use ‘doodling’ as an alibi (‘It’s just a doodle’), is an in-between realm, where extended forms of doodling, such as those characteristic of Mediumistic Art, can be found. Marginal drawings, that can be seen as disobedient or escapist, have a long history, from those in mediaeval manuscripts, via 18th century bank ledgers (Gombrich 1999), right up to the delirious ‘scribblings’ of early 20th century psychotic art (Prinzhorn 1922). In many of these examples there is a clear connection between what could be called graphic truancy and a complex system of conventions that governed proper writing and representation, and that kept ornamental excursions in restraint. Like them, the doodle’s relation to these rules is both playful and aggressive, yet subliminally it is a dependent one. Far from being completely free-range, most doodling involves shifting between various registers- alphabetic, physiognomic, ornamental – each of which has its own conventions. The extent to which this is a conscious choice is often undecidable: for example, the disruption of alphabetic legibility by gestural or decorative elements (the distinction between the two ultimately breaks down) that is supposedly symptomatic of psychotic art could be seen as either compulsive or ironic, but its author’s silence leaves us guessing. Because of this paradoxical combination of the anarchic and the law-abiding, doodling throws into relief many of the conceptual difficulties surrounding ‘automatism’ and the unconscious laws that are assumed to govern it. Like Freud’s verbal ‘free association’, what appears to be free-range inscription turns out to display patterns that can be seen as having a subliminal or ‘unconscious’ structure. There are interesting questions here as to whether these ‘deep structures’ are mainly formal, or whether they have a psychological significance, for example in terms of a primitive psychoanalytic symbolism. Certainly the early vogue for interpreting doodles shows a popularised version of Freudian ideas: as one of the best-selling doodle books put it ‘While doodles appear to be aimless pixillations they are in reality accurate pictures of the Subconscious Mind. They are psychic blueprints of man’s inner thoughts and emotions that have slipped from the deeps of memory onto paper.’ (Arundel 1937, p. x) Yet, as we shall see, most doodles have a mundane, and often clichéd character. This could, of course, reflect the fact that our unconscious preoccupations- sex, money or ambition, for example- are stereotypical; but it is just as likely to reflect the fact that even the expression of our inner worlds is shaped by the same set of linguistic and pictorial conventions. Doodling is perhaps one of the most widespread forms of drawing, and one that doesn’t depend on technical skill or professional experience: indeed some artists might envy the doodler’s apparent innocence, or their supposed access to the Unconscious. However, these images of the doodle are mirages: in reality doodling is also habitual, banal or repetitive. In 1937 a London evening paper ran a doodle competition, resulting in some 9000 entries. Collecting doodles is, as I know from my own experience, a somewhat arbitrary business, and soliciting them is no more reliable; but, judging from the samples illustrated in the paper published by three psychiatrists on this material (Guttmann, Maclay & Mayer-Gross 1937) the trawl seems to have included many doodles that could be called ‘average’ in both a statistical and an artistic sense. Their analysis of the drawings is fairly basic, though this is not surprising in view of the size of the material. One thing is obvious, and that is that doodles are hybrid and contain many different elements on a small scale: so faces, writing and ornamental detail contribute 60% each, with objects closely following at 55%. Interestingly, there were few (12%) purely ornamental doodles. In the end the authors ascribe the repetition and monotony of motifs to a ‘primitive’ collective psychology. If we go back to Prinzhorn’s ambitious attempt to establish a model for the various directions that the ‘configurative urge’ can take, we find that its most fundamental form consists of ‘aimless, unorganised scribbling’ (Prinzhorn p 14). But he had to admit that.’…even the simplest scribble… is, as a manifestation of expressive gestures, the bearer of psychic components, and the whole of psychic life lies as if in perspective behind even the most insignificant form-element.’ (Ibid. p 42). A scribble is certainly more rudimentary than a doodle, but what he illustrated as ‘scribble’ or ‘decorative drawing’ is often not just what we might now call a doodle, but is sometimes a kind of graphic fugue, with a complex structure that it is hard to attribute to instinct alone. From this starting-point Prinzhorn suggests there are three basic paths of development: representational, symbolic and ‘ordering’ (ornamental). These categories are not dissimilar from those arrived at by Guttmann and his colleagues; but in both cases they are cultural as much as instinctual, though both could be said to be ‘unconscious’ in a non-psychoanalytic sense. Just as verbal automatism is surprisingly obedient to grammatical or syntactical conventions, so graphic automatism tends to play around pictorial ones. One problem here is how this automatism is to be reconciled with our interest in self-expression. A great deal of everyday doodling reveals a popular or collective lingua franca that is surprisingly anonymous. When we ascribe a certain repetition or permutation of motifs to ‘instinct’, ‘automatism’ or label them ‘fundamental form constants’ (Navratil 1978) we invoke mechanisms that are largely impersonal; but then one could say the same of the psychoanalytic symbolism, whether Freudian or Jungian that is sometimes applied to them. It is, rather, the individual inflection given to these processes that interests us, and here graphology is a useful model (and it also made a significant contribution to ‘reading’ doodles). A Masson or Pollock drawing, for example, may display various prototypical modes of mark-making, but it is their personal signature that we value most. This tension is only a more dramatic version of the one that comes into play between an individual artist and the collective idioms of art. At the same time, part of this fascination is with what could be called the image of automatism or unconscious form production, with all its attendant fantasies about inspiration, possession, compulsion and obsession. Doodling could be described as a distant cousin of full-fledged automatism. It takes place with an intermittent ‘lowering of consciousness’, a fluctuating level of self-awareness, whereas automatism is usually associated with trancelike states, and these can be understood either as a cause or as an effect of the unconscious creative process. This is partly due to the limitations of time and space under which most doodling occurs. When these no longer apply, when there is nothing to inhibit or interrupt it, doodling is amplified, both in its scale and in its intensity. Perhaps the absence of external constraints leads to an increase in internal ones: significantly, its more extended versions in Outsider Art- most obviously in mediumistic drawing- are often said to induce a kind of auto-hypnosis. I call such extended drawings ‘meta-doodles’ because they have the same absent-minded and self-generating character as doodles, but in more concentrated form. There is an obvious fit here with Spiritualist beliefs in dictation by spirits: besides possibly providing an umbrella under which to shelter, these offer explanations that match the artist’s actual experience as well, or better, than psychological theories. Like the label ‘doodle’, Spiritualist beliefs gave permission for unbridled modes of inscription to run riot without having to risk being called ‘art’. As in doodles, the idiom of these meta-doodles blends together alphabetic, physiognomic and landscape elements with more ‘abstract’ coralline textures in which they are often embedded (eg Lonné). We can clearly see a kind of divinatory or Rorschach process at work here, where recognisable forms and shapes are read into suggestive textures, and there may also be a converse effect whereby such forms are eroded or obscured by patterns, or by informal mark-making, just as happens in doodling. Nevertheless, there are also examples of Mediumistic art in which there is strict symmetry and stereotypical repetition (eg Crépin, Lesage). Where their creators have left any accounts of their work, there are predictable references to feeling that they are just acting as a conduit for forces that are outside their control. Most of these explanations concentrate on the authority- usually spirits- ultimately responsible for the work, rather than on the process itself; but then it is in the nature of automatism that one can only really talk about the beginning and the end of this dictation, rather than what goes on in between. This brings me to another unexplored aspect of doodling: the phenomenology of its creation. Because most doodlers are ashamed of their distraction (though recent research from the University of Plymouth suggests that doodling can in fact help concentration), and perhaps also on account of its temporary nature (the meeting ends, the caller hangs up) there are few accounts of how a doodle comes into being: analysis concentrates on the final result and takes little notice of the process. As with many other kinds of drawing, the latter has to be deduced from the marks themselves. In looking at any drawing, and also at handwriting, we cannot help a subliminal and embodied identification with the gestures that we imagine to have been responsible for it. Most right-handers, for example, prefer to cross-hatch diagonally from upper right to lower left. But doodling also offers us an inside view into drawing. Because we may have used them ourselves, we can feel our way into some of the strategies of doodling: the tension between rectilinear and curvilinear, symmetry and the escape from it, the elaboration of geometrical forms, the invention of facial features and architectural constructions, as well as more negative effects such as blacking out. Some doodling is repetitive and soothing, some is restless or impatient; but, as in the case of fully automatic work, it’s difficult to know the extent to which this is a cause or an effect of the drawing process itself. We could almost see doodling as a miniature graphic gym in which different movements and rhythms are exercised in succession, and these can soon become habitual or second nature. Here, as we shall see, there are interesting analogies with Klee, whose drawings often seem to set up rules or constraints in order to provoke disruptions of them. One of the most intriguing descriptions of these effects at work in doodling comes from Worringer (1911): it is coloured by the opposition between the organic and natural and the geometric and man-made that first appeared in his ‘Abstraction and Empathy’ (1908), and predates the official birth of the doodle. In tracing ‘beautiful, flowing curves’, he wrote, ‘our inner feeling unconsciously accompanies the movement of our wrist’, whereas in a contrary tendency ‘the pencil will move wildly and violently over the paper and instead of the beautiful, round, organically tempered curves, there will be a hard, angular, ceaselessly interrupted, jagged line, of the most powerful vehemence of expression’, and here ‘the reflex sensation is not accompanied by any feeling of satisfaction, for we have the impression that we are being coerced by some alien, imperious will’ (p 43). Even more vivid is his detailed account of this: ‘At every break, at every change of direction, we feel how forces suddenly checked in their natural course are blocked; how, after this instant’s arrest, they pursue, with a momentum increased by the obstruction, a new direction of movement. And the more frequent the breaks, the more numerous the obstacles, the more powerful will be the impetus at the points of rupture, the more forceful each time will be the onrush in a new direction…’ Here I am reminded of watching a video of Jochem ven der Spek’s Tekenmachine in which a crab-like device crawls randomly about within a rectangular frame, bouncing off its edges: it leaves a variable track of twin black lines, but two swivelling rods behind it make white lines which can overlay or erase them. The result is a self-renewing and selfeffacing drawing that is like an infinite abstract drawing or doodle. We’ve looked at some examples from the golden age of doodling, but what about the modern doodle? The extent to which doodling may have evolved is an interesting question. There are some obvious technical factors: the invention of the biro, for example, has made more continuous drawing possible. The fact that the doodle has become a recognised phenomenon has led to a number of popular books on the subject, many of which, whilst purporting to facilitate doodling, are rather prescriptive. There are also numerous on-line sites where people share doodles and exhibit their work: there are even some programmes that will turn any drawing, no matter how simple, into an increasingly complicated doodle-like form. Nevertheless it seems, from my experience as a university lecturer, that the genre still persists in something like its original form. This ordinary doodling conjures up a number of scenarios, and again whilst many of these have to be deduced or imagined, they can also be corroborated from our own doodling experience. Some perhaps start with testing a pen, others with some kind of meander that may then engage in some kind of conversation with itself, generating various textures and patterns (contours, hatching, grids, loops, tangles), then perhaps elaborating some of these into frames or other territories that are claimed and more or less fully occupied. At some stage bits of faces, bodies (human or animal), buildings, machinery etc may suggest themselves (including shorthand versions of cartoon characters), and these may begin to interact: weapons will shoot at targets, creatures pursue one another. There can also be abstract ‘narratives’, in which, for example, curved and rectilinear shapes fight it out, perhaps even reaching some compositional truce. To what extent is any of this automatic? Or rather, what does using the word do to our imagination of the doodling process? In its strongest forms, ’automatic’ suggests something like instinctual pre-programmed patterns, autonomous mechanisms that, once set in motion, tend to run their course unconsciously. But in doodling we often encounter forms that have grown out of the working process itself, or that follow ‘automatically’ one from another only in the way that clichés or stereotypes do. If in a doodle repetitions occur, patterns are generated and other kinds of formal elaboration engaged in, with some sort of logic to them, these structures probably derive from something more complex and interactive than a simply predetermined sequence. They may owe something to muscular or kinetic factors, local associations of memory or coincidence, popular motifs that are ‘in the air’, as well as to some episodic sense of composition, such as filling in gaps and avoiding monotony. This is not unlike what happens in other kinds of exploratory drawing. Good examples can be found in the work of Paul Klee. Despite his famous statement ‘A line goes out for a walk, so to speak, aimlessly for the sake of the walk’, anyone who attempts this soon finds out how hard it is to stop the line from going somewhere, and hence seeming to show some kind of ‘aim’, and the repetitive or banal nature of much doodling confirms this. One solution is to allow something to develop, so that it almost seems to be following some sort of rule, and then interrupt its progress or even contradict it, as in Worringer’s description. Again, this can occur on a half-conscious level without having to be purely automatic. In Klee’s case we have plenty of examples of graphic perigrinations that behave like this; but we also have the kind of ‘laws’ that feature in his pedagogical notes, which seem to offer an analysis of them. It’s often difficult to tell whether these are descriptive or prescriptive: perhaps their relation to his work is not unlike that of a doodler who knows something about the literature, but manages not to let this interfere with the invention of his doodling. Even in the case of drawings that purport to be fully automatic, such as André Masson’s Surrealist drawings from the late 1920s, the same questions arise. Because there is a deliberate choice to abandon conscious control, there is a performative aspect to such drawing, even if this is private: hence it is perhaps the image of automatism, rather than its literal reality, that matters here. Certainly Masson’s drawings from this period have the look of automatism and resemble some mediumistic work (such as Raphael Lonné) in their calligraphic texture. He manages to distribute cursory fragments of bodies- nipples, eyes, hands, sexes- within a vestigial ‘landscape’ in ways that are unusually even-handed. This is almost like the ‘even-floating attention’ prescribed in psychoanalysis, yet here the artist applies it to himself, and, perhaps, paradoxically, only a trance-like state of suspended attention enables this. As he later wrote ‘Physically, you must make a void in yourself; the automatic drawing taking its source in the unconscious, must appear as an unforeseen birth. The first graphic apparitions on the paper are pure gesture, rhythm, incantation, and as a result: pure scribble. […] When the image appears one must stop. (Masson 1961) Again, at its humbler level, the doodle has some supporting evidence to offer us: an informal tangle of lines can suddenly suggest something, which a mere stroke can confirm, But then the doodle may get caught up in this, and literally revolve around it, whereas there is something slippery and polymorphously perverse about Masson’s idiom. What I have tried to show is that the doodle, despite being promoted as a popular non-art form of drawing, has its own subliminal connections with key elements of Modernism, and can still tell us a lot about the processes- both graphic and psychological- at work in ‘finer’ forms of art.