11. Regional Engagement and Competing Regionalisms (2006)

advertisement

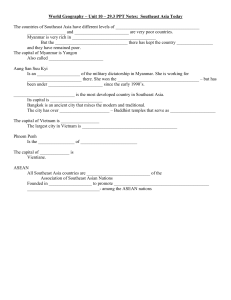

Australia and the Asia-Pacific R. James Ferguson © 2006 Lecture 11: Regional Engagement and Competing Regionalisms Topics: 1. Regionalism and Regionalization in the Asia-Pacific Area 2. Regional Processes: Beyond Values and Identity Politics 3. Asian Regional Cores Verses the Wider Asia-Pacific? 4. Multiple Cores Or Tiered Multipolarity? 5. Challenges To Regionalism and to an Indo-Pacific Tiered-multipolar System 6. Bibliography, Resources and Further Reading 1. Regionalism and Regionalization in the Wider Asia-Pacific As we have seen, no single organisation or group of organisations, covers the governance of the entire Indo-Pacific region, with only relatively limited organisations such as APEC and the ASEAN Regional Forum covering different aspects of trade and security cooperation. Even within Southeast Asia and South Asia, the construction of regional organisations (ASEAN and SAARC, see weeks 6 and 10) has been a gradual process with only limited integration and institutionalisation of these groups. The East Asian Summit (EAS) process based on the ASEAN-PlusThree (APT), has begun to emerge through 2003-2006, but it remains to be seen how strong this will be in shaping the wider region, especially since it suffers from tensions over membership, differences between Chinese and Japanese viewpoints, and a circle of activity that tends to overlap the ASEAN-Plus-Three and the ARF (Strategic Comments 2005. A clear-cut definition of a region can no longer be given on narrow geographical grounds, and is not merely based on physical proximity. Strong linkages and flows of information, money, people, affiliation or shared concerns and threats are needed form a region: The literature on new regionalism stresses several key linkage factors as necessary conditions under which regionalism or regional integration can take place among a group of states, including linkage by geographical proximity and by various forms of shared political, economic, social, cultural, or institutional affinities. Regions are also defined by combinations of geographical, psychological, and behavioural characteristics. (Kim 2004, p40). Put simply, political regions are not ‘natural’: they are ‘socially constructed and politically contested’ (Kim 2004, p45), they can be built up on historical experience or destroyed by conflict and new trends. Just as modern nations and nationalism projects are partly ‘imagined communities’ (see Anderson 1991), regional grouping are also imagined and invested in by political leaders, domestic audiences, civil society, corporations, and governments (He 2004, p119). Shared security concerns and complexes can also drive regional processes to some degree (see Buzan &Waever 2003): this was partially the case of ASEAN and remains an important factor for the ASEAN Regional Forum. Likewise, multilateral and regional groups may increase 1 the security and ‘voice’ of small and medium powers (He 2004, p121), part of the background ASEAN, APEC and to a lesser degree IOR-ARC. How far they can restrain great powers, however, dependents upon relative power balances in the wider region and whether the stronger powers need a 'concert' or alliance system to support their wider needs and agenda (see below). In part, this slow progress has been driven by the great diversity of the region, as well as by pressing national and sovereign needs by many Asian states still going through national-building processes over the last fifty years. For Southeast Asia: Southeast Asia is arguably the most diverse region in the world. Whether it is measured in terms of differences in economic development, divergent social and religious traditions or differing political regimes, there are few places where such diversity is woven into the very fabric of national life. Indeed, there are considerable grounds for questioning whether what we think of as contemporary Southeast Asia constitutes a region at all. And yet, despite this remarkable difference at the level of individual nations, Southeast Asia has also given rise to some of the most enduring transnational and regional institutions in the developing world. This paradox is at the heart of one of the most distinctive features of modern Southeast Asia: despite the national diversity that is its defining feature, there are a number of region-wide processes that have given Southeast Asia both a particular identity and a set of additional political, economic, social and even environmental dynamics that have in turn shaped national outcomes. (Beeson 2004, p1) In turn, we can question how deep this integration as been, with limited supranational aspects, with sovereignty and decision making being retained at the level of national governments, and organisations such as ASEAN largely working through inter-governmental agreements, voluntary treaties with little formal enforcement, and an ongoing dialogue process. This has in part been maintained by the non-interference concept with the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation (TAC), but in reality the region is moving towards the understanding that shared action is needed on shared problems. 2 Religious Diversity in Southeast Asia: Mosque in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam (Photocopy copright R. James Ferguson 2002) The diversity of Southeast Asia is complicated by its multi-ethnic and multireligious populations, even within one state, by diversity among nations as to wealth, developmental level, governmental style and religion, as well as sub-regional diversity among South Asia, Southeast Asia, Northeast Asia, the South Pacific, South American states (within APEC and in intensified trade relations with China and North-east Asia), and developed states with European cultural features such as Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States. Some of this diversity can be seen in Table 1 below, where even states with dominant religious groups also have significant religious minorities, e.g. Christians, Buddhists and Hindus in Indonesia. Even in Vietnam there are Christian minorities, Chinese sub-communities, and a small Muslim community. Table 1 (modified from Beeson 2004) Country Brunei Population million) .344 Cambodia 12.6 Indonesia Lao PDR Malaysia Myanmar Philippines 208.9 5.4 23.8 48.3 78.3 Singapore Thailand 4.1 61.1 Vietnam 79.5 (approx. Government Type Main Religion [Constitutional] Monarchy Constitutional Monarchy (from 1993) Democratic Republic Communist Procedural Democracy Military Junta Democracy Islam Procedural Democracy Constitutional Monarch/Democracy Communist Buddhism Islam (plus others) Buddhism Islam (plus others) Buddhism (plus others) Christianity (plus Muslim minority) Taoism (plus others) Buddhism (plus others) Buddhism (plus others) One key point is that regional processes are not always driven by similarity and convergence, though this may be required in the long term. Rather, complementarity among economies, services and development level can also provide strong regional flows. Furthermore, regional organisations can also be driven by crisis and the requirement for crisis management and preventive diplomacy. Thus, the first phase of ASEAN regionalism from 1967 was driven by the need to reduce political tensions among member states, especially Indonesia and Malaysia, and the desire to reduce great power interventions in local conflicts (see lecture 6). The second phase of ASEAN regionalism after 1998 was driven in part by a reaction to the Asian financial crisis of 1997-1998, and that East Asian states could not rely on a supportive financial and economic environment being generated by the U.S. and other Western states (for different phases of regionalism, see Kim 1998, pp41-42). Likewise, a web of bilateral ties, including free trade agreements under negotiation, have also begun to shape the region, e.g. Australian negotiations with Singapore, Thailand, the U.S., China and Japan, plus a range of proposed free trade agreements focused on Singapore, Korea, and Japan (see Kim 2004, pp56-57). It is important to distinguish between regionalization and regionalism: 3 To make sense of these differences, it is useful to make a widely employed initial conceptual distinction between processes of regionalization on the one hand, in which the private sector and economic forces are the principle drivers of regional integration, and regionalism, in which self-consciously pursued political projects drive closer transnational cooperation on the other. One of the most noteworthy comparative qualities of the Southeast Asian experience in this regard is that regional integration has primarily been uncoordinated and principally driven by multinational corporations and the evolving logic of cross-border production strategies. (Beeson 2004, pp7-8) Of course, there are strong interactions between regionalization and regionalism. Transnational regionalization processes will make regionalism projects more acceptable to political and economic elites. In turn, regionalism projects tend to create a more transparent civil and economic space, and promote free trade and other multilateral frameworks, e.g. AFTA, the AIA, plus ASEAN’s agreements with China, Japan (ASEAN-Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership) and India (via and FTA with ASEAN) that are gradually making trade and standards more compatible through 2003-2012 (He 2004, p106), though the ASEAN-Chinese Free Trade Agreement (ACFTA) seems most likely to lock into place first, perhaps causing some ‘angst’ in Tokyo (Kim 2004, p51). We should also note that the China-ASEAN FTA does not include Taiwan, unlike APEC (He 2004, p115). The ‘whole idea is to establish a comprehensive and close relationship between ASEAN and China involving an FTA, and cooperation in finance, regional development, technological assistance, macroeconomic cooperation, and other issues of common concern’ (Cai 2003). Individual agreements with ASEAN are likely to come into play before any formal, wider East Asian Free Trade Area (EAFTA), which has now been shifted into the group of medium-range projects by the ASEAN-Plus-Three (Kim 2004, p56). Likewise, the ASEAN-India efforts to build a free-trade agreement will take time to move beyond a wide range of exceptions and limitations (Gaur 2003), though some 'early fruits' of this process will result in some 105 products having tariffs cut as early 2007 (Xinhua 2005; see lectures 6 & 10). Political elites have accepted that a conscious regionalism also helps countries to cope with globalization, and give some economic and developmental support to regimes (Beeson 2004, p10) with limited democratic credentials, e.g. in Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam. Thus, ‘regionalization can be said to breed regionalism’ (Kim 2004, p40). However, in turn, regionalization make it possible for governments to consider developing shared values, norms, aspirations (Kim 2004, p40), and in cases of deep integration over the long term, a certain layer of regional identity or at least shared cultural processes may be developed. However, it may be dangerous to either to assume or mandate some notion of a shared identity when cultural system remain diverse, as in East Asia. Some general aspirations for minimum standards in terms of treatment of citizens and peaceful codes of conduct (e.g. in the South China Sea) have also begun to emerge, but has had only a limited impact on countries such as Myanmar. Likewise, pluralism and democratisation, though gaining regionally, e.g. Indonesia's transition, remain problematic norms for countries such as Vietnam and PRC, and have not yet become part of a more inclusive pattern of regional governance (see lecture 6). At present, neither Australia nor the US, even with the earlier aid of Thailand, the Philippines and Indonesia, seem able to insist on a democratic-led form of regionalism in the Asia-Pacific (contra Terrill 2005). In turn, the stability of democracies in Thailand and Philippines is limited, and even in Indonesia there are major concerns about the delivery of basic rights in 4 regions such as Aceh (slowly improving through 2005-2006) and West Papua (Strategic Comments 2006). 2. Regional Processes: Beyond Values and Identity Politics In the past, efforts have been made to built regional projects in Asia, either on the basis of some shared identity, on resistance to Western colonialism and power, and on the notion of shared ‘Asian values’ or at least a ‘shared ASEAN way’. One of the earliest models for this was the intense interaction among earlier kingdoms, mandala systems of prestige and influence and extended trading networks for over two millennia (see Wolters 1992; Higham 1989). Beyond this, however, there was an attempt in the early 20th century to shape a sense of Pan-Asian values and PanAsianism in contrast to Western colonial dominance and narrow patterns of nationalism, a trend of though influencing thinkers as diverse as Gandhi, Rabindranath Tagore (the great Bengali writer and thinker), Aurobindo, Sun Yat-sen, Rin Kaito and Major General Kenji Doihara and others (He 2004, pp107-108; Duara 2001). Such ideas would soon founder on Japanese militarism through the 1930s, and come to be rejected in India, China and Korea (He 2004, p110). The Asian values debate would be revived through the 1980s and 1990s as part of the debate over the causes of revived ‘tiger’ economies in East Asia, leading to a reappraisal of the relationship of traditional values systems (including Confucianism and Taoism) to modern life (see Dupont 1996). Though a tempting move politically, and supported at time by governments resisting outside influence or seeking legitimation for governments with limited democratic credentials, this has been a problematic path for Asian regionalism. In the worst case scenario, support for ‘Asian values’ verses ‘Western’ human rights may be a way of justifying ‘soft authoritarian’ regimes with limited degrees of political freedom (Beeson 2004, p11), e.g. in Malaysia, Singapore, and in a different form in PRC. For a time this ‘New Asianism’ was given some support in Japan, e.g. via the search to create a new, shared contemporary Asian culture, thereby allowing a secondary and safe outlet for some Japanese nationalism (He 2004, p114), but this now seems a minor trend. In the long run, regionalism based on exclusive cultural systems or anti-Westernism may be a kind of ‘trap’ since modern and Western ideas and technology are freely used in much of urban Asia, and trade linkages into the U.S., Canada and Australasia remain important (adapting He 2004, p121). Likewise, emerging middle-classes throughout Asia share elements of modernism drawn from Western culture. The ‘ASEAN Way’ and Asian values did to some degree drive the proposal for an East Asian Economic Grouping (EAEG) which would exclude non-Asian states on the basis of culture and identity (He 2004, p112), given most vocal support by former Prime Minister Mahathir of Malaysia from 1990 as at first an alternative to APEC. This project was attacked by the U.S. and not supported by Australia, while Japan and South Korea in the end were unwilling to effectively exclude or downgrade relations with major trade partners across the Pacific. This led to the subsequent downgrading of EAEG to the East Asian Economic Caucus (EAEC), a loose grouping within APEC (Kim 2004, p46). However, this grouping was reborn both as the Asian ‘table’ within the ASEM (Asia-Europe Meetings), and as the ASEAN-Plus-Three from 1997 (He 2004, p112), though now driven largely by economic and security 5 concerns. However, narrower grouping might meet the short-term needs of countries such as Malaysia or PRC if they feel that their national needs are too readily constrained by US or Australian influences. The problem of founding East Asian or Southeast Asian regionalism on shared values or identity has been summarised: Indeed, the defining feature of East Asia is not a singular set of “Asian values,” whatever that may mean, but linguistic, cultural, and religious diversity. Such diversity is pronounced not only between East Asian states but also within particular Asian states, mostly in Southeast Asia. Paradoxically, the most vocal and stringent rallying cries for “Asian values” have come from Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia (and also China), where multicultural, multireligious, and even multi-ethnonational fault lines produce deep fissures. . . . East Asia is defined by its plurality of cultural and historical traditions. (Kim 2004, p54). On this basis, it has been suggested that East Asian regionalism is largely driven forward by ‘intergovernmental collaboration’ on free trade and a security dialogue, but ‘lacks systematic thinking, an ethical foundation, and a region-centric framework’ (He 2004, p119). On this basis, too, regional commitment towards a truly participation-based regionalism, with strong inputs from civil society, and convergence on democracy, will remain limited (Acharya 2003). Rather, over the last two decades, regionalism in the Asia-Pacific has been driven in part by wider concerns over great-power dominance, and then by the impact of globalisation on relatively weak and developing states. In this sense, regional groups can be buffers preparing nations for wider globalisation trends (e.g. the ASEAN Free Trade Area and APEC preparing Southeast Asia and China for the wider opening of their economies to the world economy via WTO processes), but also act as conduits for ongoing trade and investment liberalization (as in the AIA, ASEAN Investment Area). Indeed, elite support for regionalism in Southeast Asia had already been conditioned by the transnational patterns of trade and production run via business and corporations: Yet even the most cursory glance at the empirical data associated with ‘globalization’ reveals that global flows of trade and investment, and even the transnational production strategies of multinational companies, reveal a distinction regional bias. In other words, whatever we take globalization to be, it is powerfully shaped by national and regional forces as countries, companies and a range of other actors attempt to respond to the challenges of external competition and the transnational integration of edconomic and political activity. In this context, globalization is simply a convenient shorthand for that complex array of processes – economic, political, social and even strategic – that have transformed the context within which states conduct themselves and which have constrained their autonomy as a consequence. If this contention about diminished autonomy has merit as a general statement about the status of contemporary states, It is doubly true of Southeast Asia, where the modern, independent state is a relatively recent invention, and where the sovereignty of states has already been compromised to some extent. (Beeson 2004, p3) Put another way, the states of East Asia are ‘coping with forces and demands of both regionalization and regionalism amid the twin pressures of globalization from above and localization from below (so-called glocalization)’ (Kim 2004, p39). Thus, regional processes have been revived as conduits of change as well as ways of sustaining the decision making ability of groups of states (thus indicating that 6 Thomas Friedman’s truism, “It’s globalization, stupid!’, may not always be true, see Kim 2004, p43). Likewise, these factors have boosted environmental and ecological pressures for many of the developing countries of Asia. Environmental problems affect local, national, regional and global groups, depending on the particular problem. Many resource and environmental problems, e.g. the Haze, over-used river systems, polluted coastal waters, or over-exploited fisheries, are often transboundary in nature and require regional cooperation. Growing consumption rates, industrialisation, growing urban populations (40% of Southeast Asia lived in cities through 1999, a ratio that may double by 2025), and energy consumption rates that double approximately every 12 years have led to increased pressure on the environment and its resources (Elliott 2004, pp180-181). There have also been trends of intensified agriculture, great usage of pesticides and fertilizers, and overtaxing of soil fertility (Elliott 2004, p183). Possible GDP losses due to environmental and related health problems have been estimated in the order of 3%-8% for Southeast Asia (Elliott 2004, p183; see earlier discussions in week 3 and 7). 3. Asian Regional Cores Verses the Wider Asia-Pacific? One key question that has emerged through 1997-2006 has been the debate over whether Indo-Pacific processes will remain strongly mandated by U.S. policy, or whether stronger cores of decision-making and policy formation have emerged in Southeast Asia, East Asia (perhaps focused on future PRC initiatives), and to a lesser degree in South Asia. Here there may be differences in the vitality of the ASEAN and ASEAN-Plus-Three-Groupings verses the more diffuse ARF and APEC groups, partly based on ‘great power’ competition in the wider Asia-Pacific (see Bell 2003). Indeed, Samuel Kim has suggested that the ‘center of gravity for economic regionalism has already shifted away from the U.S. dominated APEC, which suffers from partial ‘paralysis and marginalization’, towards the ASEAN+3’ (Kim 2004, p51, p62). Thus: . . . East Asian regionalism is on the rise. The new regionalism in the area is based on the shared embrace of economic development and well-being and the shared sense of vulnerability associated with the processes of globalization and regionalization. Greater regional cooperation is one of the few available instruments with which East Asian states can meet the double challenge of globalization from above and localization from below. Operating in a regional context, the East Asian states can “Asianize” the response to globalization in a politically viable form. (Kim 2002, p61) However, it must be noted that this is not based on deep integration, nor strong convergence. China, for instance, as used the idea of ‘finding common ground while preserving differences” (qiutong cunyi) in its diplomacy (Kim 2004, p60), suggesting some limit to community building in East Asia. This is a gradual process, rather than the construction of strong rule-based institutions with deep integration. Total GDP of East Asia almost reached that of Europe and North America form the early 1990s, accounting for around 30% of global GDP through the early 1990s, while through 2002, Northeast Asia held 48% of global foreign exchange reserves (Kim 7 2004, p44). However, this wealth has only begun to be translated into global power project and coherent regionalism, and does not yet have the ability to set global agenda, norms and regimes. Samuel Kim has suggested that one of the key organisations that can begin to translated this wealth into institutional power is the ASEAN-Plus-Three, with the grouping having ‘the broader strategic objective of enmeshing an increasingly powerful China into a regional financial regime in the making’ (Kim 2004, p48). PRC has become both a more forceful player in this type of regionalism, as well as promoting ‘continental regionalism’ into Central Asia via the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), perhaps as part of wider Eurasian strategy, in part focused on energy access for future development (He 2004, p116; see further Xiang 2004). This has also included some willingness to engage in regional financial diplomacy. PRC’s willingness not to devalue its currency after the 1997-1998 crisis, and currency swaps among central banks through the ASEAN-Plus-Three (mandated after the Chiang Mai Initiative, CMI, and with the support of the Asian Development Banks) aimed at strengthening regional currency reserves to avoid any future financial collapse and contagion n the region (Kim 2004, p49). The CMI was designed as a measure to work alongside normal IMF operations: At the ASEAN Plus Three Finance Ministers Meeting in Chiang Mai in May 2000, one of the main topics of discussion was how to develop a regional financing arrangement that could be utilized to maintain financial stability in the East Asian region. At that time, the discussion on the expansion of the ASEAN swap arrangement (ASA) to include all ASEAN countries and increase its size to US$1 billion by the ASEAN central banks was near its final stage. The ASEAN Plus Three countries decided to combine the expanded ASA with a network of bilateral swap arrangements (BSAs) among the ASEAN Plus Three countries to establish the first regional financing arrangement called the "Chiang Mai Initiative" (CMI). The expanded ASA, while relatively small in size compared with other international financing facilities, is unconditional and designed for quick activation and disbursement. It became effective in November 2000 and allows member banks to swap their local currencies with major international currencies - such as the U.S. dollar, Euro, and yen - for a period of up to six months, and for an amount up to twice their committed amount under the ASA. (18) In line with its role as a rapid disbursement facility, a member's swap request for temporary liquidity or balance of payments assistance will be confirmed through the Agent Bank, (19) which will inform and consult with the rest of the members to assess and process the request as expeditiously as possible. (Manupipatpong 2002) By 2004, thirteen major swap arrangements had been made, with a total value of US$32.5 billion, indicating a degree of ‘monetary regionalism’ (He 2004, pp105106). Likewise, this broad level agenda and the November 2002 Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea has reduced hot conflicts in the South China Sea, even if the issue of sovereignty and boundaries has not been resolved (Kim 2004, p49). It is possible to envision several futures for East Asian regionalism. In one of these, ASEAN may be able to create its triple economic, security and socio-cultural community through 2012-2020, ASEAN Concord II (see Hew & Soesastro 2003) thereby beginning a process that deep integration that may well may it a strong core of regional process in the 21st century. This core could then moderate cooperation through outreach into South and Northeast Asia. However, as we have seen, serious 8 progress on this triple community will be slow and has yet to face numerous developmental and democratic challenges (see lecture 6). Other possibilities include: This opens up a variety of “futurible” scenarios for the emerging East Asian regional order: a hegemonic model (whether Sino-centric or U.S.-centric); an intraregional bipolar balance-of-power model (Sino-Japanese); a multipolar ‘concert of power” condominial model; a collective security model; an Asia-Pacific or East Asian economic community model; and a pluralistic security community model. (Kim 2004, pp61-62 All of these models are partly in progress at present, leading to some internal competition among different patterns of regionalism, but also to decision paths in the future as certain options become more or less viable. In one view, Asian regionalism, both in Southeast and Northeast Asia, has been shaped by the recognition of the dominant power of the United States: In addition, what underlies Asian perceptions of regionalism is the awareness of a dominant US power in Asia. The unipolar system, under which US power penetrates East Asia and maintains the fragmentation and division of East Asia, has made difficult and even impossible the emergence of a common Asian identity. With the presence of the US factor, Asian regionalism can only be achieved without Asian identity. Asian regionalism can only be a ‘supplement’ to the USA, rather than a force against it. Asian regionalism has to be Pacific-centric regionalism with its door open to the USA (He 2004, p107) This is partly true, especially of under the forceful foreign policy of the Bush administration through 2001-2003, and has only begun to slowly change through 2003-2006. As we have seen, even Southeast Asian regionalism is problematic if based on a shared identity, and even more so for any wider grouping. On this basis, regionalism is more likely to driven by shared benefits, patterns of cooperation, and the limited, complementary mobilisation of cultural values and products, rather than some imagined identity. Here, ASEAN from 2003 has been driven towards creating a stronger economic and security process, explicitly set out in the ASEAN Concord II process from 2003, and the East Asian Summit process from 2005. In turn, ASEAN and PRC in particular have found the ASEAN-Plus-Three as a strong venue for an active and progressive international policy that has reduced some regional tensions (Straits Times 2005). China has found this a non-threatening forum from which to extend its foreign policy, while ASEAN has sought to moderate growing Chinese power through mutual engagement with South Korea and Japan, and drawing India, Australia and New Zealand into the EAS process. Through 2005-2006 this has led to the beginning of a deeper East Asian Summit (EAS) process. Perhaps more important than the EAS agenda itself has been use of the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation, already signed by the ASEAN states, China, Japan in 2004, India and conditionally by Australia. It has been viewed as a background norm for expectations in this summit process (Pakistan has also signed the TAC). The TAC has a set of loose but important principles: a. Mutual respect for the independence, sovereignty, equality, territorial integrity and national identity of all nations; 9 b. The right of every State to lead its national existence free from external interference, subversion or coercion; c. Non-interference in the internal affairs of one another; d. Settlement of differences or disputes by peaceful means; e. Renunciation of the threat or use of force; f. Effective cooperation among themselves. (in Heller 2005, p127) Thus, the EAS should promote strong political dialogue focused on Asian issues, but is not set to be the basis of a future 'Asian Union' (see Bowring 2005). This has lead to some shift in Australian policy, which has wanted to be part of this process, but has been reluctant to sign the TAC without reservation. Through July 2005 the Howard government that it would be willing to sign the TAC, but that this should not interfere with existing Australian alliances, especially with the U.S. Through mid2005 the background politics to this was worth noting: Australia has been officially invited to join the first East Asia summit after it agreed to accede to the South-East Asian non-aggression pact. The invitation meant Australia would for the first time be involved in the evolution of the east Asian community, the Foreign Minister, Alexander Downer, said last night. He also revealed Australia had adopted a similar model to the one South Korea used for signing the Treaty of Amity and Co-operation, by exchanging correspondence setting out Australia's and ASEAN's understanding of the pact. . . . Mr Downer said Australia's invitation would mean "for the first time ever Australia will be involved in the evolution of an east Asian community". "That's an enormous issue for Australia," he said. Australia's reluctance to sign the treaty was because of concerns it would conflict with its obligations under the ANZUS alliance and would inhibit its ability to criticise ASEAN countries on human rights issues. The move came as Burma finally bowed to pressure from its ASEAN neighbours yesterday and gave up the 2006 chairmanship of the regional forum, saying it needed to focus on national reconciliation. The decision closed the chapter on one of the most intensive lobbying efforts the forum has seen, and allows ASEAN to avoid messy confrontations with Western dialogue partners such as the US and the European Union. (Banham & Levett 2005) This nuanced shift also reduced the rhetoric of pre-emption in the region. Moreover, though the US has been concerned about its exclusion from the EAS, it has encouraged both Indian and Australian involvement (Kelly 2005). This probably improves Australia's diplomatic leverage, but once again it will have to avoid being seen as promoting US interests within a regional forum. Australia that made it clear that the TAC moderated it relations with Southeast Asia, but did not override other agreements: In July 2005, Canberra announced that it would, despite misgivings, sign the TAC (which it did on the eve of the summit in December). At the same time, Foreign Minister Alexander Downer emphasised four ‘understandings’(effectively reservations) that Canberra had agreed with its ASEAN counterparts: that signing the TAC should not affect Canberra’s existing security arrangements (notably its alliance with America), Australia’s rights and obligations under the UN charter, or Australia’s 10 relations outside Southeast Asia, and that ASEAN could intervene in disputes involving Australia only after an invitation from Canberra. (Strategic Comments 2005) In the long run, we may see two different 'cores' emerging in the Asia-Pacific, one focused on the US and one on China (Kelly 2005) - if so, Australia will need to balance its relations and move towards low levels of competition among its two major 'patrons'. In the long run, Australia and Japan may act as bridges to ensure that US interests are not totally sidelined within the EAS. Moreover, the ASEAN community itself seems to have realised that these general principles of cooperation, 'amity' and non-interference may not be enough to drive the organisation forward. On this basis, through late 2005 they took the key elements of earlier agreements and outlined a values-based agenda for the future, the ASEAN Charter (ASEAN 2005): * Promotion of community interest for the benefit of all ASEAN Member Countries; * Maintaining primary driving force of ASEAN; * Narrowing the development gaps among Member Countries; * Adherence to a set of common socio-cultural and political community values and shared norms as contained in the various ASEAN documents; * Continuing to foster a community of caring societies and promote a common regional identity; * Effective implementation as well as compliance with ASEAN’s agreements; * Promotion of democracy, human rights and obligations, transparency and good governance and strengthening democratic institutions; * Ensuring that countries in the region live at peace with one another and with the world at large in a just, democratic and harmonious environment; * Decision making on the basis of equality, mutual respect and consensus; * Commitment to strengthen ASEAN’s competitiveness, to deepen and broaden ASEAN’s internal economic integration and linkages with the world economy; * Promotion of regional solidarity and cooperation; * Mutual respect for the independence, sovereignty, equality, territorial integrity and national identity of all nations; * Renunciation of nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction and avoidance of arms race; * Renunciation of the use of force and threat to use of force; non-aggression and exclusive reliance on peaceful means for the settlement of differences or disputes; * Enhancing beneficial relations between ASEAN and its friends and partners; * Upholding non-discrimination of any ASEAN Member Countries in ASEAN’s external relations and cooperative activities; * Observance of principles of international law concerning friendly relations and cooperation among States; and * The right of every state to lead its national existence free from external interference, subversion or coercion and non-interference in the internal affairs of one another. (ASEAN 2005) What is new, is that if the Charter is accepted and ratified, ASEAN it 'will confer a legal personality to ASEAN and determine the functions, develop areas of competence of key ASEAN bodies and their relationship with one another in the overall ASEAN structure' (ASEAN 2005), thus suggesting that this norms would guide the structure and functioning of ASEAN in future. If so, 'democracy, human rights and obligations, transparency and good governance and strengthening democratic institutions' would be a strong expectation, though once again limited by ' respect for the independence, sovereignty, equality, territorial integrity and national identity' (ASEAN 2005). It remains to be seen, then, whether this really is a way 11 forward for the organisation, but it does at least suggest an entrenching of current trends towards an Southeast Asian community focused on dialogue and shared needs amid a turbulent wider environment. It is thus viewed internally as 'a firm foundation for ASEAN in the years ahead and to facilitate community building towards an ASEAN Community' (ASEAN 2005) 4. Multiple Cores Or Tiered Multipolarity? As we have seen, the regionalism the Indo-Pacific have been moderated by the rise of great powers regionally, who to some degree moderate or entangle the power of the remaining global superpower, the United States. In such a system, China is usually viewed as the rising contender for regional hegemony, using both traditional avenues of sovereign power (military modernisation, moderate power projection, missile and nuclear technology, sustained and rapid growth in GDP), as well as new forms of diplomacy and influence, now routed along multilateral channels (engagement in regional projects, the APT, the China-ASEAN FTA, the ARF, the EAS, APEC, the SCO, the Code of Conduct for the South China Sea, the AP6 or Asia-Pacific Partnership on Clean Development and Climate, and its new, global energy and resource politics, including a new focus on Latin America, see Malik 2006). Likewise, India has also been touted as a rising power over the next two decades, and has perhaps been partly viewed as a counterbalance to Chinese longterm interests, though large internal challenges and needs still need to be met (see lecture 10). Another project that has been shared by some of these emerging powers is an emphasis on multipolarity in the global system was one way of enhancing national power, regional abilities, and as a way of moderating the impact of U.S. policy. Multipolarity has at times been favoured by countries such as China, Russia, India, and France, as well as by the EU in trade and governance areas. Rather than accept a bipolar or unipolar world system, key states including China, France, Russia and India have long argued that today several major centres of power need to be recognised within the world system (Xinhua 2000; Dixit 1999). On this basis, the possibility of sustained hegemonic dominance or preponderance of power by the remaining superpower seems unlikely, since such power soon generates 'countervailing forces', contesting the legitimacy of such a role. (Guehenno 1998, p16). Furthermore, the 'balance of power' model that was the basis of traditional realist models must be adapted in the light of the rise of geo-economic power, the influence of international institutions, and the impact of globalisation (see Vasquez 1997; Christensen & Synder 1997). At the very least, it may be necessary to include 'balance of threat' and 'balance of interests' factors to explain alliance behaviour, and to include the influence of decision-makers and public perceptions in order to arrive at theories that explain actual inter-state behaviour (Vasquez 1997; Christensen & Snyder 1997). Hence, we need to consider not just 'poles' of power but levels and structures: No singe hierarchy describes adequately a world politics with multiple structures. The distribution of power in world politics has become like a layer cake. The top military layer is largely unipolar, for there is no other military comparable to the United States. 12 The economic middle layer is tripolar and has been for two decades. The bottom layer of transnational interdependence shows a diffusion of power. (Harkavy 1997) On this basis, the U.S. remains as the global superpower, but cores of economic power have developed below this in Europe, Northeast Asia and North America. Thereafter, the rise of India, Southeast Asia, and more slowly South America have complicated this picture. Thus thinkers such as Huntington and Nye argued that a hybrid system of uni-multipolarity had emerged from the 1990s onward: The post-Cold War period has witnessed 'a strange hybrid' of these in what Huntington terms a uni-multipolar international system, with one superpower and several major powers. Within this unique system, the only superpower may veto action on key international issues taken by a combination of major powers, but it also needs the co-operation of others to solve disputes effectively. n their accounts, both Nye and Huntington have reservations about whether the current international order is a genuine unipolarity. (Kan 2004) Multipolarity has been viewed by neo-realists as intrinsically less stable than bipolar systems, and that in general the fewer number of great powers in an international system the better (Friedberg 1993). However: The validity of this claim is by no means self-evident and, indeed, has been the object of a prolonged, heated, and ultimately inconclusive scholarly debate. Disagreement on the comparative merits is unresolvable on either deductive grounds (clever arguments can be made on both sides of the question) or, because of the relative rarity of bipolar systems, on the basis of historical evidence. In any case, with the sudden collapse of the old bipolar order, a new and more pressing issue has begun to assert itself: What may account for differences in the functioning of systems of similar structure? And, specifically, why is it that some multipolar systems have proven more stable (in terms both of their duration and of the level of conflict within them) than others? (Friedberg 1993) Thus, for example, the concert of power system helped stabilise much of Europe after the end of the Napoleonic wars down till the 1860s. Likewise, Coral Bell has suggested that a ‘status quo’ alliance of the US, the EU, and Japan, backed up by Russia, PRC (if ‘brought on board’) and Pakistan might emerge (Bell 2003, pp41-42; see further lecture 4). Beyond this a range of developing powers, including Indonesia and South Africa, might play a bigger role in the future (Bell 2003, p42), to which we could add the loose convergence of ASEAN and Indian interests. Through 2005-2006 its seems unlikely that this wider status quo power system can emerge in the short term, in part due to tensions between Japan and China, and in part due to China and Russian efforts in building an alternative power system in Eurasia based on the SCO. While the dangers of multipolarity are recognised, including the possibility of competition and alliance politics among these key powers (now expressed through the concepts of 'strategic partnerships' and 'special relationships'), a constructive, cooperative multipolarity can also be envisaged. In particular, it is necessary to move beyond the simple concept of power-balancing among several discrete national powers, where complexity, lack of quickness in seeking balance, the role of revisionist powers, strategic miscalculation or misperceptions (Christensen 1997), and irrational alliance building can undermine any sense of security offered by the system. (Harkavy 1997; Friedberg 1993). In the current global system, power is also nested within regional systems, within global patterns of trade and financial flows, partly 13 arbitrated through international institutions which radically alter the nature of both the system and the poles of power at play. This means that multipolar power patterns are also played out through influence in multilateral institutions, and in economic, trade and energy politics. This terminology of multipolarity was mobilised as part of reninvigorating IndiaRussia relations. In October 2000 the two countries signed 'a declaration on strategic partnership on greater defence and military-technical cooperation and joint effort to fight international terrorism, while giving a boost to the economic relationship between the two countries.' (INDOLink 2000). Although the long-term benefits from this relationship can be debated in comparison to growing US linkages to India (see lecture 10), the term 'strategic partnership' in this context is highly significant, since this is the same terminology used in the crucial Sino-Russian rapprochement since 1996 (Chengappa 2000). This terminology seems, at least from the Russian point-ofview, to be part of an emerging emphasis on developing greater multipolarity in the international system (Srivastava 2000, pp334-335). Likewise, in the 2000 Summit between EU and India efforts were outlined towards the building of a 'new strategic partnership' in which the 'EU and India are important partners in the shaping of the emerging multipolar world' of the 21st century.1 At present, the global system has not so much developed a 'simple multipolarity' of roughly equal great powers, but rather a regional multipolarity of several regional subsystems, sometimes terms 'multi-multipolarity' (Friedberg 1993). In such a setting, countries such as India and PRC, and groupings such as ASEAN, can increase their regional and global profile through conscious employment of a the model of multipolarity, combined with a circles of engagement approach. However, this 'tiered multipolarity' system in the wider India-Pacific also has several dangers (see Kan 2004; Buzan & Waever 2003; Buzan, Jones & Little 1993). Multipolar patterns can slip from regional cooperation which still engages the remaining superpower towards more contentious system where unresolved conflicts and intensified competition could turn the system into a contest for regional or subregional hegemony. Here the role of smaller power and weaker alliance partners can also be problematic, especially when combined with new challenges to the existing international set of regimes. Likewise, it is possible that contending claims can lead to an erosion of leadership and direction in the international system. In one view: What Washington has most essentially lost is acquiescence to its leadership. Other powers no longer have any compunction about opposing U.S. policies and preferences when it is not in their own independent interests to follow them. It is a game of every power for itself, in which each regional power center cooperates with others when it shares common interests with them and opposes them when interests conflict. The result is the absence of a single paradigm of world order or even of a coherent pattern of alliances. In their place are coalitions of convenience that -- taken together -- have no consistent direction. (Weinstein 2004) 1 "EU-India Summit Joint Declaration", 28 June 2000 [Internet access at http://europa.eu.int/external_relations/india/simmit_06_00/joint_declaration.htm]. 14 5. Challenges To Regionalism and to an Indo-Pacific Tiered-multipolar System These leads to a series of questions, challenges and problems that challenge both regionalism and a stable tiered-multipolar system in the Indo-Pacific: 1) Is a new but unstable nuclear club emerging across the Ind-Asian zone, including established nuclear powers (US, China), accepted non-NPT powers (India and Pakistan) and emerging nuclear powers that make seek to creep across the line towards weaponisation and missile capabilities (North Korea, Iran)? 2) Has progress in the ASEAN-Plus-Three, the East Asian Summit process and strong growth in PRC given China a pivotal role in future East Asian Regionalism? Can it moderate possible tensions with Japan and the U.S. over potential ‘leadership’ in some regional agenda? Will PRC be willing to take up a strong but accountable regional and international role? (see Kim 2004, p58). 3) Is ASEAN strong enough and coherent enough to remain the core driver of wider ARF, ‘ASEAN-plus’ and EAS processes? 4) Are states with major unsatisfied claims on the international system, such as Pakistan, North Korea and potentially Taiwan, adequately factored into plans for regional stability? 5) Do new security organizations need to be created if the ARF remains relatively weak and unable to fully engage ‘preventive diplomacy’? 6) Do middle powers such as Australia have sufficient influence on regional organisations, bearing in mind tensions through 1997-2006? If we list different groups, what leverage and influence does Australia have in them (APEC, ASEAN Regional Forum, IOR-ARC, CSCAP, EAS, etc)? 7) Can environmental cooperation provide a focus for regional resource management in the long term? Are a number of smaller and weaker states in Asia and the Pacific unsustainable in the medium term? 8) Is there a clear split between East Asian regionalism and wider Asia-Pacific processes? Can these processes be re-linked constructively? 9) Can democracy become more central to Indo-Pacific regional processes, or would this act more as a blockage if tackled too directly (for such proposals, see Terrill 2005; ASEAN 2005). 10) Can a stable system of 'power and need' balances be established in the IndoPacific during the early 21st century? 15 6. Bibliography, Resources and Further Reading Resources Asian studies on the Web with a wide range of links will be found at http://coombs.anu.edu.au/WWWVL-AsianStudies.html Quite good coverage on political events in Asia will be found in the South China Morning Post, one of Hong Kong's leading newspapers, on the Web at http://www.scmp.com/ A wide range of political and governance issues are addressed in the East Asia and the Pacific Region, section of the World Bank Group Webpage at http://lnweb18.worldbank.org/eap/eap.nsf Power and Interest News Reports (PINR) provide critical reporting and analysis of current news, Asia-Pacific Affairs and world issues at http://www.pinr.com/ Further Reading ASEAN "Kuala Lumpur Declaration on the Establishment of the ASEAN Charter", Kuala Lumpur, 12 December 2005 [Access via wwew.aseansec.org/18030.htm] BEESON, Mark (ed.) Contemporary Southeast: Regional Dynamics, National Differences, Basingstoke, Palgrave, 2004 BELL, Coral A World Out of Balance: American Power and International Politics in the TwentyFirst Century, Sydney, The Diplomat magazine and Longueville Books, 2003 BUZAN, Barry & WAEVER, Ole Regions and Powers : The Structure of International Security, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2003 HE, Baogang “East Asian Ideas of Regionalism: A Normative Critique”, Australian Journal of International Affairs, 58 no. 1, March 2004, pp105-126 KAN, Francis Yi-hua "East Asia in a unipolar international order and Europe's role in the region", Asia Europe Journal, 2 no .4, Dec 2004, pp497-522 [Access via Infotrac Database] KELLY, Paul "Howard's Asian Balancing Act", The Australian, 29 June 2005, p13 KIM, Samual S. “Regionalization and Regionalism in East Asia”, Journal of East Asian Studies, 4, 2004, pp39-67 [Access via Ebsco Database] PYE, Lucian W. "Civility, Social Capital: Stability and Change in Comparative Perspective: Three Powerful Concepts for Explaining Asia", The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 29 no. 4, Spring 1999 [Access via Infotrac Database] SHINN, James (ed.) Fires Across the Water: Transnational Problems in Asia, N.Y., Council on Foreign Relations, 1998 SUBRAMANIAM, Surain "The Asian values Debate: Implications for the Spread of Liberal Democracy", Asian Affairs, 21 no. 1, Spring 2000, pp19-35 [Access via Infotrac SearchBank] Bibliography ACHARYA, Amitav A New Regional Order in South-East Asia: ASEAN in the Post-Cold War Era, Adelphi Paper 279, London, IISS, August 1993 ACHARYA, Amitav "Realism, Institutionalism, and the Asian Economic Crisis", Contemporary Southeast Asia, 21 no. 1, April 1999, pp1-29 ACHARYA, Amitav “Democratisation and the Prospects for Participatory Regionalism in Southeast Asia”, Third World Quarterly, 24 no. 2, 2003, pp375-390 AISIN-GIORO, Pu Yu From Emperor to Citizen: The Autobiography of Aisin-Gioro Pu Yi, trans. W.J.F.Jenner, Beijing, Foreign Languages Press, 1989 ALAGAPPA, Muthiah (eds.) Political Legitimacy in Southeast Asia: The Quest for Moral Authority, Stanford, Stanford University Press, 1995 16 ALDRICH, Richard J. "Dangerous liaisons: post-September 11 intelligence alliances", Harvard International Review, 24 no. 3, Fall 2002, pp50-54 ALLISON, Graham & TREVERTON, Gregory F. (eds.) Rethinking America's Security: Beyond Cold War to New World Order, N.Y., W.W. Norton, 1992 ANDERSON, Benedict "The Idea of Power in Javanese Culture", in Holt, Claire et al (eds.) Culture and Politics in Indonesia, Cornell University Press, 1972 ANDERSON, Benedict Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, London, Verso, 1991 AQUINO, Norman P. "May 14, 2001 elections: a referendum of sorts", Businessworld, 2 April 2001 ASEAN "Kuala Lumpur Declaration on the Establishment of the ASEAN Charter", Kuala Lumpur, 12 December 2005 [Access via wwew.aseansec.org/18030.htm] AYOOB, "From Regional System to Regional Society: Exploring Key Variables in Regional Order", Australian Journal of International Relations, 53 no.3, 1999, pp255-256 BAKER, Mark “U.S. Relents as ASEAN Talks with Hun Sen”, Sydney Morning Herald, 28 July 1997 [Internet Access] BALL, Desmond & KERR, Pauline Presumptive Engagement: Australia's Asia-Pacific:Security Policy in the 1990s, St. Leonards, Allen & Unwin, 1996 BANHAM, Cynthia & LEVETT, Connie "Australia to Form Closer Asian Ties", Sydney Morning Herald, 27 July 2005 [Internet Access via http://www.smh.com.au/news/world/] BARME, Geremie “Alarm Bells from Suspicious Shores”, Australian, 7 April 1997, p11 BEESON, Mark (ed.) Contemporary Southeast: Regional Dynamics, National Differences, Basingstoke, Palgrave, 2004 BELL, Coral "Changing the Rules of International Politics", AUS-CSCAP Newsletter No. 9, February 2000 [Internet Access at http://aus-cscap.anu.edu/Auscnws9.html] BELL, Coral A World Out of Balance: American Power and International Politics in the Twenty-First Century, Sydney, The Diplomat magazine and Longueville Books, 2003 BENGWAYAN, Michael "Water Management Poses Challenges for Southeast Asia", The Earth Times, 9 February 2000 [Internet Access] BONAVIA, David Deng, Hong Kong, Longman Group (Far East) Ltd, 1989 BOWRING, Philip “Malaysians Should force Reform Without a Revolution”, International Herald Tribune, 19 November 1998, p10 BOWRING, Philip "Towards an 'Asian Union'?", International Herald Tribune, 18 June 2005 [Internet Access] BUSZYNSKI, Lesek "ASEAN Security Dilemmas", Survival, 34 no. 4, Winter 1992-93, pp90-107 BUZAN, Barry & WAEVER, Ole Regions and Powers : The Structure of International Security, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2003 BUZAN, Barry, JONES, Charles & LITTLE, Richard The Logic of Anarchy: Neorealism to Structural Realism, New York, Columbia University Press, 1993 BYRNES, Michael Australia and the Asia Game, London, Allen & Unwin, 1994 CAI, Kevn G. “The ASEAN-China free trade agreement and East Asian regional grouping”, Contemporary Southeast Asia, 25 no. 3, December 2003, pp387-404 [Access via Infotrac Database] CHANDA, Nayan "The External Environment for Southeast Asian Foreign Policy", in WURFEL, David & BURTON, Bruce (eds) The Political Economy of Foreign Policy in Southeast Asia, N.Y., St. Martin's Press, 1990, pp54-71 CHENGAPPA, Raj "Sincerely Yours", India Today, 16 October 2000 [Internet Access] CHRISTENSEN, Thomas J. "Perceptions and Alliances in Europe, 1865-1940", International Organization, 51 no. 1, Winter 1997, pp65-97 [Internet Access via Infotrac] CHRISTENSEN, Thomas J. & SNYDER, Jack "Progressive Research on Degenerative Alliances", American Political Science Review, 91 no. 4, December 1997, pp919-923 CHURCH, Peter (ed.) Focus on Southeast Asia, Sydney, Allen & Unwin, 1995 CORBEN. Ron "Thais Threaten Retaliation Over Border Raids", Weekend Australian, 6-7 May 1995, p14 CROUCH, Harold The Army and Politics in Indonesia, Ithaca, Cornell University, 1978 DAE-JUNG, Kim "Asians Must Take the Lead With Burma", Burma Debate, June/July 1995, pp4-10 DAVIS, Glyn "Culture as a Variable in Comparative Politics: A Review of Some Literature", Politics, 24 no. 2, November 1989 DAVIS, Leonard The Philippines: People, Poverty and Politics, N.Y., St. Martin's Press, 1987 17 DELLIOS, Rosita Modern Chinese Strategic Philosophy: The Heritage from the Past (1), Bond University, The Centre for East-West Cultural and Economic Studies, Research Paper 1, April 1994 DIXIT, Aabha "Indian Navy: Working Out of a Financial and Operational Crisis?", Asia Pacific Defence Reporter, March-April 1996, pp19-20 DIXIT, Aabha "India's Defence Policy and Production - Challenges and Opportunities", Asia-Pacific Defence Reporter, Jan-Feb. 1996, pp8-9 DIXIT, J.N. "External Threats and Challenges: An Overview of India's Foreign Policy", World Affairs, 3 no. 1, January-March 1999, pp28-39 DUARA, Prasenjit “The Discourse of Civilization and Pan-Asianism”, Journal of World History, 12 no. 1, Spring 2001 Access via Infotrac Database] DUC, Hiep Nguyen & TRUONG, Truong Phuoc “Water Resources and Environment Around Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam”, Electronic Green Journal, December 2003 [Access via Ebsco Database] DUPONT, Alan “Is There An ‘Asian Way’?”, Survival, 38 no. 2, Summer 1996, pp13-33 DUPONT, Alan "Beware of the Growing Thirst: Looming Asian Food Shortage Poses a Security Threat", Australian, 1 August 2000, p13 Economist, “Uncle Ho’s Legacy”, 25 July 1998, p31 ELEGANT, Simon “Silent Movie: Gag order Halts Public Debate Over Anwar’s Dramatic Case”, Far Eastern Economic Review, 15 October 1998, p20 ELLIOT, Lorraine “Environmental Challenges, Policy Failure and Regional Dynamics in Southeast Asia”, in BEESON, Mark (ed.) Contemporary Southeast: Regional Dynamics, National Differences, Basingstoke, Palgrave, 2004, pp178-197 ELSON, John "Viet Nam Loosens Up", Time, 1 February 1988 EMMERSON, Donald K. & SIMON Sheldon W. Regional Issues in Southeast Asian Security: Scenarios and Regimes, NBR Analysis, Volume 4 No. 2, July 1993 ENGARDIO, Pete "An Elder Statesman Surveys Asia's Future", Business Week, November 29, 1993, p26 ENV “Agent Orange Alert", Environmental News Network, 17 March 2000 [Internet Access] Environment Custom Wire “ADB to Help Develop Flood Management for Meking River”, 15 March 2004a [Access via Ebsco Database] FERGUSON, R. James "Complexity in the Centre: The New Southeast Asian Mandala", The Culture Mandala, 1 no. 1, November 1994, pp16-40 FERGUSON, R. James "Positive-Sum Games in The Asia-Pacific Region", The Culture Mandala, 1 no. 2, September 1995, pp35-58 FERGUSON, R. James “The Dynamics of Culture in Contemporary Asia: Politics and Performance During 'Uneven Globalisation'“, Paper Presented at the Asian Cultures At the Crossroads: An East-West Dialogue in the New World Order Conference, November 16-18 1998, Hong Kong Baptist University (Co-sponsored by Ohio University) FERGUSON, R. James “Shaping New Relationships: Asia, Europe and the New Trilateralism”, International Politics, 4, January 1998, pp1-21 FERGUSON, R. James "Nanning and Guangxi: China's Gateway to the South-West", The Culture Mandala, 4 no. 1, December 1999-January 2000, pp48-69 [Library, and Internet Access at http://rjamesferguson.webjump.com] FRIEDBERG, Aaron L. "Ripe for Rivalry: Prospects for Peace in Multipolar Asia", International Security, 18 no. 3, Winter 1993, pp5-33 FU, Zhengyuan "Continuities of Chinese Political Tradition", Studies in Comparative Communism, 24 no. 3, September 1991 FURTADO, Xavier "International Law and the Dispute over the Spratly Islands: Whither UNCLOS?", Contemporary Southeast Asia, 21 no. 3, December 1999, pp386-404 GAUR, Seema “Framework agreement on comprehensive economic co-operation between India and ASEAN: first step towards economic integration”, ASEAN Economic Bulletin, 20 issue 3, December 2003, pp283-291 [Access via Infotrac Database] GEERTZ, Clifford Negara: The Theatre State in Nineteenth-century Bali, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1980 GIRLING, J.L.S. People's War: Conditions and Consequences in the China and South East Asia, N.Y., Praeger, 1969. 18 GUÉHENNO, Jean-Marie "The Impact of Globalisation on Strategy", Survival, 40 no. 4, Winter 19981999, pp5-19 HAN, Vo Xuan & BAUMGARTE, Roger "Economic Reform, Private Sector Development, and the Business Environment in Viet Nam", Comparative Economic Studies, 42 no. 3, Fall 2000, pp1-30 HANDLEY, Paul "Sacred and Profane", Far Eastern Economic Review, 4 July 1991, pp21-25 HARKAVY, Robert E. "Images of the Coming International System", Orbis, 41 no. 4, Fall 1997, pp569-590 HARRIS, Stuart "The Economic Aspects of Pacific Security", Adelphi Paper 275, Conference Papers: Asia's International Role in the Post-Cold War Era, Part I, (Papers from the 34th Annual Conference of the IISS held in Seoul, South Korea, from 9-12 September 1992), March 1993, pp14-30 HARKAVY, Robert E. "Images of the Coming International System", Orbis, 41 no. 4, Fall 1997, pp569-590 HASSAN, Shaukat Environmental Issues and Security in South Asia, Adelphi Paper 262, London, IISS, Autumn 1991 HASSAN, Mohamed Jawhar & RAMNATH, Thangam (eds.) Conceptualising Asia-Pacific Security: Papers Presented at the 2nd Meeting of the CSCAP Working Group on Comprehensive and Co-operative Security, Kuala Lumpur, ISIS Malaysia, 1996 HE, Baogang “East Asian Ideas of Regionalism: A Normative Critique”, Australian Journal of International Affairs, 58 no. 1, March 2004, pp105-126 HELLER, Dominik "The Relevance of the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) for Regional Security in the Asia Pacific", Contemporary Southeast Asia, 27 no. 1, April 2005, pp123-145 [Access via Infotrac Database] HENDERSON, Jeannie Reassessing ASEAN, Adelphi Paper 328, London, IISS, May 1999 HEW, Denis & SOESASTRO, Hadi “Realizing the ASEAN Economic Community by 2020: ISEAS and ASEANISIS Approaches”, ASEAN Economic Bulletin, 20 no. 3, 2003, pp292-296 HIEBERT, Murray "Taking to the Hills: Massive Migration Changes the Face of Dac Lac", Far Eastern Economic Review, 25 May 1989, pp42-3 HIEBERT, Murray "Changing faces: Personnel Moves Mooted for Communist Congress", Far Eastern Economic Review, 13 June 1991, p18 HIEBERT, Murray & AWANOHARA, Susumu "The Next Great Leap", Far Eastern Economic Review, 22 April 1993a HIEBERT, Murray & AWANOHARA, Susumu "Ready to Help: Agencies Prepare Their Menus of Projects", Far Eastern Economic Review, 22 April 1993b HIGHAM, Charles The Archaeology of Mainland Southeast Asia: From 10 000 B.C. to the Fall of Angkor, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1989 HOLSTI, K.J. "The Comparative Analysis of Foreign Policy: Some Notes on the Pitfalls and Paths to Theory", in WURFEL, David & BURTON, Bruce (eds) The Political Economy of Foreign Policy in Southeast Asia, N.Y., St. Martin's Press, 1990, pp9-20 HUGO, Graeme & STAHL, Charles "Labour Export Strategies in Asia", Paper presented at The 4th International Conference on Development and Future Studies: Economic and Social Issues of 21st Century Asia and Developing Economies, Equatorial Hotel, Bangi, 2-4 September 1997 HUNTINGTON, Samuel P. "The Clash of Civilizations?", Foreign Affairs, Summer 1993, pp22-49 HUYNH, Frank & STENGEL, Heike "Sustainable Development: Challenges to a Developing Country", in THAN, Mya & TAN, Joseph (eds.) Vietnam's Dilemmas and Options: The Challenge of Economic Transition in the 1990s, Singapore, ASEAN Economic Research Unit, pp259-284 INDOLink "India, Russia Sign Strategic Partnership, Nine Other Pacts", 3 October, 2000 [Internet Access] JACOB, Paul "Don't Create Unrest While Suharto is Away", Straits Times, 10 July 1996 [Interactive Internet Access] JAWHAR, Mohamed "The Making of a New Southeast Asia", in BALL, Desmond & HORNER, David (eds.) Strategic Studies in A Changing World: Global, Regional and Australian Perspectives, Canberra, Strategic and Defense Studies Centre, Research School of Pacific Studies, ANU, 1992, pp290-319 KAN, Francis Yi-hua "East Asia in a unipolar international order and Europe's role in the region", Asia Europe Journal, 2 no .4, Dec 2004, pp497-522 [Access via Infotrac Database] KAUTILYA Arthasastra, trans. by R. Shamasastry, Mysore, Mysore Printing and Publishing House, 1967 19 KELLY, Paul "Howard's Asian Balancing Act", The Australian, 29 June 2005, p13 KIM, Samual S. “Regionalization and Regionalism in East Asia”, Journal of East Asian Studies, 4, 2004, pp39-67 [Access via Ebsco Database] KING, Dwight "Indonesia's Foreign Policy" in WURFEL, David & BURTON, Bruce (eds) The Political Economy of Foreign Policy in Southeast Asia, N.Y., St. Martin's Press, 1990, pp74100 KORANY, Bahgat "Analyzing Third-World Foreign Policies: A Critique and Reordered Research Agenda", in WURFEL, David & BURTON, Bruce (eds) The Political Economy of Foreign Policy in Southeast Asia, N.Y., St. Martin's Press, 1990, pp21-3 LEE, Lai To, "The South China Sea: China and Multilateral Dialogues", Security Dialogue, 30 No. 2, June 1999, pp.165-178 LEGGE, J.D. Sukarno: A Political Biography, London, Allen Lane, 1972 LOESCHER, Gil Refugee Movements and International Security, Adelphi Paper no 268, London, IISS, 1992 M2 Presswire "World Bank: Donors Pledge Support as Vietnam Enters the 21 st Century", 15 December 2000 MACKERRAS, Colin Eastern Asia: An Introductory History, Melbourne, Longman Cheshire, 1992 MAGNO, Francisco A. "Environmental Security in the South China Sea", Security Dialogue, 28 No.1, March 1997, pp104-107 MALIK, J. Mohan "Patterns of Conflict and the Security Environment in the Asia-Pacific Region: the Post - Cold War Era", in MALIK, J. Mohan et al. Asian Defence Policies: Great Powers and Regional Powers (Book I), Geelong, Deakin University Press, 1992, pp33-52 MALIK, Mohan “India Goes Nuclear: Rationale, Benefits, Costs and Implications”, Contemporary Southeast Asia, 20 no. 2, August 1998, pp191-215 MALIK, Mohan " 'China's Growing Involvement in Latin America'', Power and Interest News Report, 22 July 2006 [Access via PINR at http://www.pinr.com/report.php?ac=view_region&region_id=18&language_id=1] MANUPIPATPONG, Worapot “The ASEAN Surveillance Process and the East Asian Monetary Fund”, ASEAN Economic Bulletin, 19 no.1, April 2002, pp111-122 [Access via Infotrac Database] MILNER, Murray Jr. Status and Sacredness: A General Theory of Status Relations and an Analysis of Indian Culture, Oxford, OUP, 1994 MIN Jiayin "Ideas of Cooperation and Struggle in the Chinese Philosophy, and Its Worldwide Significance", World Futures, 31 nos. 2-4, 1991, pp181-190 MOEDJANTO, G. The Concept of Power in Javanese Culture, Yogyakarta, Gadjah Mada University Press, 1986 MURATA, Fuminori "Vietnam's Old Guard Finds New Foe: Fears of Foreign Funds Eroding Power, Straits Times, 21 May 1996 [Interactive Internet Access] MUTALIB, Hussin "Islamic Revivalism in ASEAN States: Political Implications", Asian Survey, XXX No. 9, September 1990 NATHAN, Andrew J. China's Crisis: Dilemmas of Reform and Prospects for Democracy, N.Y., Columbia University Press, 1990 NEHER, Clark D. "The Foreign Policy of Thailand", in WURFEL, David & BURTON, Bruce (eds) The Political Economy of Foreign Policy in Southeast Asia, N.Y., St. Martin's Press, 1990, pp177-203 O’BRIEN, William E. “The nature of shifting cultivation: stories of harmony, degradation, and redemption”, Human Ecology: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 30 no. 4, December 2002, pp483-502 [Access via Infotrac Database] PARAMESWARAN, P. "State's Push for Islamic Law Splits Malaysia", The Weekend Australian, November 27-28, 1993, p15 PENDERS, C.L.M. The Life and Times of Sukarno, London, Sidgwick & Jackson, 1974 PERELOMOV, L. & MARTYNOV, A. Imperial China: Foreign-Policy Conceptions and Methods, trans. by V. Schneierson, Moscow, Progress Publishers, 1983 PYE, Lucian Asian Power and Politics: The Cultural Dimensions of Authority, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1985 PYE, Lucian W. "Civility, Social Capital: Stability and Change in Comparative Perspective: Three Powerful Concepts for Explaining Asia", The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 29 no. 4, Spring 1999 [Access via Infotrac SearchBank] 20 ROSENBERG, David "Environmental Pollution Around the South China Sea: Developing a Regional Response", Contemporary Southeast Asia, 21 No.1, April 1999, pp137-141 SALIBURY, Harrison E. The New Emperors - Mao and Deng: A Dual Biography, London, Harper Collins, 1992 SEGAL, G. Defending China, Oxford, OUP, 1985 SHAMBAUGH, David "Growing Strong: China's Challenge to Asian Security", Survival, 36 no. 2, Summer 1994, pp43-59 SHERIDAN, Greg "Defence Shows Its Muscle in Build Up", The Australian, October 29, 1993a, p8 SHERIDAN, Greg "Malaysia's Political Master Mixes It with the Best", The Australian, 27-1-93b, p11 SHERIDAN, Greg "Japan Cool on Pyongyang Sanctions", The Australian, November 18, 1993c, p8 SHERIDAN, Greg Tigers: Leaders of the New Asia Pacific, Sydney, Allen & Unwin, 1997 SHISH, Chih-Yu China's Just World: The Morality of Chinese Foreign Policy, London, Lynne Rienner Publishes, 1993 SIM, Susan “No Suharto Dynasty, Says Indonesian Leader's Daughter”, Straits Time Interactive, 5 May 1997 [Internet Access] SINGAPORE MINISTRY OF DEFENCE Defence of Singapore 1992-1993, Singapore, Public Affairs Department, Ministry of Defence, August 1992 SINGH, Udai Bhanu "Vietnam's Security Perspectives", Strategic Analysis, 29 no. 9, December 1999, pp1481-1492 SNELLGROVE, David L. A Cultural History of Tibet, Boston, Mass., Shambhala, 1968 SNODGRASS, Adrian The Symbolism of the Stupa, Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1985 SNITWONGSE, Kusuma "Strategic Developments in Southeast Asia", BALL, Desmond & HORNER, David (eds.) Strategic Studies in A Changing World: Global, Regional and Australian Perspectives, Canberra, Strategic and Defense Studies Centre, Research School of Pacific Studies, ANU, 1992, pp257-289 SOPIEE, Noordin "The Revolution in East Asia", Strategic Analysis, 19 no. 1, April 1996, pp5-26 SRIVASTAVA, Anupam "India's Growing Missile Ambitions: Assessing the Technical and Strategic Dimensions", Asian Survey, 40 no. 2, March/April 2000, pp311-341 STEWART, Cameron "PM's Regrets to Vietnam", The Australian, 12 April, 1994, p1 Straits Times "'Substantive Agenda" Needed for Summit", 10 June 2005, p18 Strategic Comments "The East Asia Summit: Towards a Community - or a Cul-de-Sac?", 11 no. 10, December 2005, pp1-2 [Access via http://www.iiss.org/publications/strategic-comments/pastissues/volume-11---2005/volume-11---issue-10/the-east-asia-summit] Strategic Comments "Unstable Democracies in Southeast Asia: The Philippine and Thai Crises", 12 no. 4, May 2006, p1-2 SUBRAMANIAM, Surain "The Asian values Debate: Implications for the Spread of Liberal Democracy", Asian Affairs, 21 no. 1, Spring 2000, pp19-35 TAMBIAH, S.J. World Conqueror and World Renouncer: A Study of Buddhism and Polity in Thailand Against a Historical Background, Cambridge, CUP, 1976 TARRANT, Bill "Asia-Europe Summit Reduces Cultural Gap - Mahathir", Reuters, 2 March 1996 TERRILL, Ross "A Bloc to Promote Freedom", The Australian, 19 July 2005, p13 THAPAR, R. Asoka and the Decline of the Mauryas, London, Oxford University Press, 1961 THION, Serge Watching Cambodia: Ten Paths to Enter the Cambodian Tangle, Bangkok, White Lotus, 1993 TIGLAO, Rigoberto "People Power II", Far Eastern Economic Review, 160 no. 40, 2 October 1997, pp14-15 TOWSEND-GAULT, Ian "Preventive Diplomacy and Pro-Activity in the South China Sea", Contemporary Southeast Asia, 20 No.2, August 1998, pp171-190 VASQUEZ, John A. "The Realist Paradigm and the Degenerative Verses Progressive Research Programs: An Appraisal of Neotraditional Research on Waltz's Balancing Proposition", American Political Science Review, 91 no. 4, December 1997, pp899-912 [Access via Infotrac Database] Vietnam Investment Review “MPI: Economic Growth Set to Hit 8 per cent”, 31 March 2004 [Access via Ebsco Database] VU CAN "Vietnam Face to Face with Chinese Aggression", Chinese Aggression Against Vietnam: Dossier, Hanoi, Vietnam Courier, 1979 WATSON, Adam The Evolution of International Society: A Comparative Historical Analysis, London, Routledge, 1992 21 WEINSTEIN, Michael A. ''Testing the Currents of Multipolarity", The Power and Interest News Report (PINR), 15 December 2004 [Access via http://www.pinr.com/report.php?ac=view_region&region_id=18&language_id=1] WOLTERS, O.W. "Ayudhya and the Rearward Part of the World", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, nos 3 & 4, 1968, pp166-78 WOLTERS, O.W. History, Culture, and Region in Southeast Asian Perspectives, Singapore, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1982 WORLD BANK, “$320 Million Credits Inked to Support Reforms and Poverty Reduction in Vietnam”, News Release No: 2005/22EAP, July 8 2004a [Internet Access] WORLD BANK “$49 million in credit and grant to help sustainable forest management in Vietnam”, News Release No:2005/18/EAP, 9 July 2004b [Internet Access] WRIGHT, Tony "Why Keating's Timing is Spot on for Hanoi Visit", Sydney Morning Herald, 19 Feb. 1994, p27 WURFEL, David "Conclusion" in WURFEL, David & BURTON, Bruce (eds) The Political Economy of Foreign Policy in Southeast Asia, N.Y., St. Martin's Press, 1990, pp288-316 WURFEL, David & BURTON, Bruce (eds) The Political Economy of Foreign Policy in Southeast Asia, N.Y., St. Martin's Press, 1990 XIANG, Lanxin “China’s Eurasian Experiment”, Survival, 46 no. 2, Summer 2004, pp109-122 Xinhua "France, India Share View on Multipolar World: Chirac", Xinhua News Agency, 18 April 2000 [Access via Infotrac Database] Xinhua “Vietnam's Population Growth Rate Drops to 1.4 Percent”, Xinhua News Agency, Nov 27, 2001 [Access via Infotrac Database] Xinhua “Vietnam targets exporting 450 Mln US dollars worth of timber in 2003”, Xinhua News Agency, Jan 9, 2003 [Internet Access via Infotrac Database] Xinhua "ASEAN-India FTA Set to Kick off in January" Xinhua News Agency, 6 September 2005 [Access via Infotrac Database] YAHYA, Faizal "India and Southeast Asia: Revisted", Contemporary Southeast Asia, 25 no. 1, April 2003, pp79-103 YAHYA, Faizal "Pakistan, SAARC and ASEAN relations", Contemporary Southeast Asia, 26 no. 2, August 2004, pp346-375 [Access via Infotrac Database] ZHANG, Ming "The Emerging Asia-Pacific Triangle", Australian Journal of International Affairs, 52 no. 1, April 1998, pp47-62 22