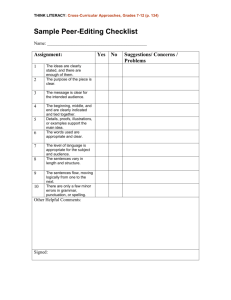

Read the Paper

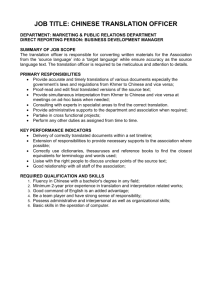

advertisement