Human Cloning and Stem Cell Research

advertisement

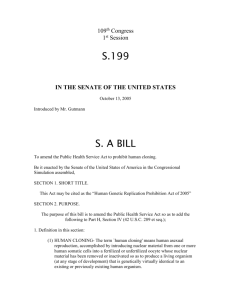

533567609 3/9/2016 3:02 AM HUMAN CLONING AND STEM CELL RESEARCH: WHO SHOULD DECIDE WHERE TO DRAW THE LINE? JUNE MARY ZEKAN MAKDISI* People hold a variety of opinions concerning where to draw the line on using human embryos for purposes of stem cell research and human cloning. Rather than commenting directly on the appeal of any particular opinion, I would like to focus on perhaps a more preliminary question: Who should make the decision about where the line should be drawn? As noted by Regine Kollek, most relevant to that issue is: “[H]ow do we want to live? As individuals, as [pockets of] societ[ies, or] as [a] global communit[y]?”1 I. INDIVIDUALS AS DECISION-MAKERS A familiar ethos of U.S. culture is one of individualism, 2 emphasizing autonomy and self-determination.3 In the context of American liberalism, autonomous decision-making places a premium on choice as it is divorced from its objective, substantive dimension. Of primary importance is the value of choice itself, protected “for its own sake”4 as an exercise of * 1. 2. 3. 4. Associate Professor, St. Thomas University School of Law; B.A., University of Pennsylvania; M.S., University of Pennsylvania; J.D., University of Tulsa College of Law. Regine Kollek, Technicalisation of Human Procreation and Social Living Conditions, in THE ETHICS OF GENETICS IN HUMAN PROCREATION 139, 157 (Hille Haker & Deryck Beyleveld eds., Ashgate Publ’g Ltd. 2000). See Peter H. Schuck, Affirmative Action: Past, Present, and Future, 20 YALE L. & POL’Y REV. 1, 91 (2002); Judith L. Maute, Pre-Paid and Group Legal Services: Thirty Years After the Storm, 70 FORDHAM L. REV. 915, 917 (2001). Kevin P. Quinn, Viewing Health Care as a Common Good: Looking Beyond Political Liberalism, 73 S. CAL. L. REV. 277, 285 (2000). Frederick Mark Gedicks, An Unfirm Foundation: The Regrettable Indefensibility of Religious Exemptions, 20 U. ARK. LITTLE ROCK L.J. 555, 563 (1998). 635 533567609 636 3/9/2016 3:02 AM NEW ENGLAND LAW REVIEW [Vol. 39:635 freedom.5 As such, any restrictions on cloning decisions could be viewed as “unwarranted restrictions” on liberty.6 Professor Kaveny observes that proponents of individual choice tend to spotlight the “hard cases.”7 For example, the public is asked to focus on a seriously ill child, and to embrace cloning or the promise of stem cell research as a means of providing a potential remedy,8 or as a means of avoiding the production of other children with serious infirmities.9 Similarly, the public is asked to accept cloning as a viable choice for couples with a biological or same-sex impediment to natural procreation.10 Empathy for the couple is garnered by a concentration on the goal: producing a genetic relationship to the child.11 This orientation of the American public toward desirable cloning ends is politically valuable. Members of society can sympathize with another’s “hard case” predicament and, by simultaneously adopting the abortion model of choice, create a separation from the substantive matter of cloning. Personal insulation from the potentially repugnant choice thereby diminishes the visceral rejection and enables cloning to be legitimized.12 Once the exercise of choice to clone is legitimized, the rare “hard cases” that were used to overcome the cloning taboo are no longer needed. As the “hard cases” drop away from view, what remains is choice discourse, which demands that others be judgment-free about the circumstances under which an individual cloning decision might be applied. Is a policy that endorses the individual as the appropriate cloning decision-maker a sound one? 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. See Erick Rakowski, Taking and Saving Lives, 93 COLUM. L. REV. 1063, 1113-15 (1993) (noting that choosing defines us as persons and manifests our rejection of tyranny). M. Cathleen Kaveny, Cloning and Positive Liberty, 13 NOTRE DAME J.L. ETHICS & PUB. POL’Y 15, 16 (1999); see also Janet L. Dolgin, In a Pod, 38 JURIMETRICS J. 47, 52 (1997) (noting that a right to clone has been justified as a manifestation of choice). Kaveny, supra note 6, at 16. Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT) cloning (coupled with human embryonic stem cell harvesting) is hailed by some as a means to find a cure. See, e.g., Susan M. Wolf et al., Using Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis to Create a Stem Cell Donor: Issues, Guidelines & Limits, 31 J.L. MED. & ETHICS 327, 327 (2003) (discussing the implications of utilizing Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis (PGD) for Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) matching). See, e.g., JOHN CHARLES KUNICH, THE NAKED CLONE: HOW CLONING BANS THREATEN OUR PERSONAL RIGHTS 17-18 (Praeger Publishers 2003); see also infra text accompanying notes 24-27 (discussing PGD cloning). See KUNICH, supra note 9, at 18. See id. at 17-18. See Kaveny, supra note 6, at 16. 533567609 3/9/2016 3:02 AM 2005]REGULATING HUMAN CLONING & STEM CELL RESEARCH 637 An important consequence of adopting individualism and its deference to liberal autonomy is that the individual decision-maker has the authority and the power to exercise eugenic control over human evolution as a whole. In effect, the destiny and make-up of our future collective society can be directed by the subjective personal preferences of a small group of individuals who have both the will and the means to command it.13 Individualized control over human destiny has rather broad implications in the context of cloning, with its potential for mass production as well as unnatural selection.14 Although, as the “hard cases” suggest, cloning could nobly be employed to reduce the presence of serious genetic diseases, it also has the potential to be used for sinister and narcissistic purposes.15 Deference to autonomous choice does not distinguish between them. A counter-argument to this rather dark picture would be to point to the growing acceptance of some form of individualized eugenic control by virtue of the approval of abortion. But when a woman decides to terminate an existing prenatal human life, negative eugenics is an unpreventable consequence to resolving another issue: resolving a conflict between the interests of a prenatal human life and the woman who would otherwise be forced to bear it, in apparent conflict with her right to bodily integrity. Thus, approving individualized control over eugenic selection in the context of abortion is not analogous to its approval in the context of cloning. Another significant difference between abortion and cloning is the effect of the eugenic practice that follows. The negative eugenics consequent to an abortion decision is confined by its requirement of an existing pregnancy and the additional limitation on numerosity, since few humans gestate during any particular pregnancy. This sharply contrasts with cloning, which is impeded with neither limitation. Cloning is proactive, positively directing a eugenic consequence as its primary objective. Since one person has the potential of dictating a particular human genetic composition and the number of copies that are to be produced, the results of positive eugenics are both qualitative and quantitative.16 13. 14. 15. 16. C.S. Lewis, rather darkly, sees the eugenic decisions of a few as a weakening of the power of future generations to control their own destiny. C.S. LEWIS, THE ABOLITION OF MAN 70-71 (1947). LOIS WINGERSON, UNNATURAL SELECTION: THE PROMISE AND THE POWER OF HUMAN GENE RESEARCH, at xiii (Bantam Books 1998). See KUNICH, supra note 9, at 20. See generally Kaveny, supra note 6, at 15 (discussing negative and positive rights in 533567609 638 3/9/2016 3:02 AM NEW ENGLAND LAW REVIEW [Vol. 39:635 Allowing individuals to choose particular characteristics permits one to consider the clone as something less than oneself.17 Thereby, individuals are authorized to decide who is deemed unworthy of human dignity. The language of personhood attempts to neutralize this reality by calling attention to the fact that a prenatal human life has not yet become a human person. But that is the same kind of argument that enabled citizens to devalue African-Americans in the middle of the 1800s.18 What has changed since then is not the intrinsic value of African-American individuals nor their objective entitlement to human dignity. Instead, it is the inclusion of them within a group labeled “persons” that has been altered. Since acknowledging worth on the basis of personhood is a policy right that may shift, there is no distinct and unmovable line protecting those currently enjoying that right.19 As the political climate changes, so too may the qualification of who may be excluded from personhood status and its corresponding protections. Another problematic consequence of favoring individualized autonomous choice is that it potentially impacts the resultant reproductive clone’s autonomous freedom in shaping his or her own destiny.20 Moreover, the clone is instrumentalized because it is produced in order to serve the ends of its producer or progenitor—whether reproductive, medicinal, or social in nature.21 Again, in the process of treating a clone as an end, one human life is permitted to be devalued as unworthy by 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. the context of cloning). Id. at 30-31. See Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393 (1856). See Michael P. Lynch, Who Cares About the Truth? THE CHRON. OF HIGHER EDUC., Sept. 10, 2004, at B6. In his explanation about why truth is important, Lynch contrasts policy rights with fundamental rights. Because policy rights are justified on the basis of a social goal, they may change as the political climate or goal shifts. Fundamental rights, on the other hand, are based on objective truth. See id. See Kaveny, supra note 6, at 30. Other sources describe the psychological impact on a clone who may be perceived as fitting into the mold of the genetic progenitor. See, e.g., Martha C. Nussbaum, Little C, in CLONES AND CLONES 338, 338-46 (Martha C. Nussbaum & Cass R. Sunstein eds., W.W. Norton & Co. Ltd. 1998); Kollek, supra note 1, at 147 (noting that “genetification,” biological determinism, elevates the impact of genetics in defining another). See, e.g., KUNICH, supra note 9, at 20 (noting instrumantalization of the clone by its use as an organ donor to the progenitor). The technical ability to produce and test clones in the context of PGD instrumentalizes all IVF embryos that are subjected to the process because only the ones that meet the specified criteria are permitted to live. See The Politics of Genes; America’s Next Ethical War, THE ECONOMIST, Apr. 14, 2001, at 21, 22 (explaining that “Baby Adam” was implanted and gestated because he was the only one of fifteen healthy embryos that was an appropriate bone marrow match for his sister). 533567609 3/9/2016 3:02 AM 2005]REGULATING HUMAN CLONING & STEM CELL RESEARCH 639 another.22 How can we, as a society, trust that individuals who are not required to justify their autonomous choices will act responsibly? Do we really want individuals, on their own, to decide what it means to clone “responsibly”? What may seem subjectively correct to the individual decision-maker may be objectively and democratically unjust.23 Do we really want to permit individuals, particularly if there is no correlative moral obligation, to make decisions on the basis of personal preferences when those personal choices have immediate and future global impact? Finally, the phenomenon of individual autonomous choice may be an illusion. Some commentators are concerned that once the technology is made available as a matter of choice, a freely-made decision about whether to employ it may be impeded by coercive external pressures.24 This would be more keenly felt by those who would otherwise choose not to make use of the technology—for their own personal autonomous reasons. What about decisions to clone that are already being made on behalf of individuals—for example, for those who agree to the pre-implantation genetic “diagnosis” (PGD) of embryos that are produced by in-vitro fertilization? This type of cloning tends to be left out of the cloning discussion—perhaps because consumers are likely unaware of the clonal nature of PGD.25 Pre-implantation genetic diagnosis is promoted as a technology that can be applied to determine the presence or absence of some gene (or chromosome) for which there is an available test.26 The PGD 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. Although my references apparently relate only to the reproductive clone, the discussion also relates to non-reproductive cloning as well as to stem cell research. The difference between reproductive and non-reproductive cloning is primarily one of labeling. See PRESIDENT’S COUNCIL ON BIOETHICS, HUMAN CLONING AND HUMAN DIGNITY: AN ETHICAL INQUIRY, at xxiii-xxv (July 2002), available at http://www.bioethics.gov/reports/cloningreport/pcbe_cloning_report.pdf. The clone under discussion is created asexually through the process of SCNT. If intended for implantation, it would be labeled a reproductive clone. If the clone produced by SCNT is not intended to be implanted, it is labeled something else, such as a “therapeutic” clone, or a clone produced for scientific research. Id. From these clones, human embryonic stem cells may be withdrawn. Id. at xxvi. The considerations under discussion are only augmented by permitting individuals to choose whether to produce SCNT clones to serve their needs. Democratic injustice can occur within a culture as well as between cultures. See, e.g., George Annas, Turning Point for the Human Species, TRIAL, July 2001, at 24, 27-29 (noting that those not employing some cloning technology may be viewed as “neglectful” parents); see also Sonia Mateu Suter, The Routinization of Prenatal Testing, 28 AM. J.L. & MED. 233, 255 (2002) (noting that prenatal diagnosis has become more an imposition than an option). See June Mary Zekan Makdisi, Involuntary Cloning: A Battery, 79 ST. JOHN’S L. REV. (forthcoming Winter 2005). See id. 533567609 640 3/9/2016 3:02 AM NEW ENGLAND LAW REVIEW [Vol. 39:635 process is described as comprising two steps. First, the in-vitro embryo is biopsied by removing one of its totipotent blastomeres. Second, the withdrawn blastomere undergoes genetic testing. Testing results diagnose the genetic composition of the embryo from which the blastomere has been withdrawn. Not specified in sources that promote PGD technology as a matter of choice is the production of a clone as the totipotent blastomere is removed from its host embryo.27 Why is the fact of cloning omitted? Perhaps it is because of the immediate outcry that came when the fact of cloning was first acknowledged.28 Perhaps by silence cloning can be accepted as a technological norm and thereby overcome any visceral rejection, as described by O. Carter Snead29 and others, that could accompany full informational disclosure at the present time. If an individual’s cloning decision may be imposed politically or engineered by medical professionals through withholding information pertinent to the decision, then true autonomous choice may not exist. In light of the other problems associated with identifying the individual as the appropriate decision-maker, perhaps it would be better to consider others as more appropriate decision-makers. II. SCIENTISTS AS DECISION-MAKERS Perhaps scientists should be the decision-makers since they have the best understanding of stem cell and cloning technology as well as the scientific and medicinal applications. Of primary concern, however, would be a scientist’s ability to appropriately balance the important social issues connected with human cloning and human embryonic stem cell research against the purely scientific or personal issues.30 The purpose of science is to advance science.31 With respect to any human experimentation, such an interest stands in direct conflict with those of the unavoidably instrumental human “subject” of the experiment. As a result, there are ample examples of bad judgments made on behalf of 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. See id. (listing disclosures of IVF/PGD clinics). See id. (referencing Hall’s announcement in 1990). O. Carter Snead is General Counsel to the President’s Council on Bioethics. Mr. Snead presented the Keynote Address at the New England Law Review’s Symposium on Stem Cell Research and Human Cloning in November of 2004. See O. Carter Snead, Keynote Address: Preparing the Groundwork for a Responsible Debate on Stem Cell Research and Human Cloning, 39 NEW ENG. L. REV. 479 (2005). Scientists who make discoveries may be driven by the accolades they receive. See Steven Goldberg, The Reluctant Embrace: Law and Science in America, 75 GEO. L.J. 1341, 1383 (1987). See id. 533567609 3/9/2016 3:02 AM 2005]REGULATING HUMAN CLONING & STEM CELL RESEARCH 641 science. There is no need to go through a parade of horribleness. It is sufficient to recall the historic Tuskeegee experiment,32 last decade’s Gelsinger gene therapy investigation,33 and the more recent clinical trials testing child antidepressants.34 In each case, clouded judgment or a lack of appreciation for basic human dignity interfered with sound decisionmaking. Compounding the difficulties that scientists have in balancing human interests with scientific ones when deciding whether to begin a course of investigation, is the additional problem of evaluating post-scientific advances. These assessments determine whether further experimentation is justified. When interpreting experimental results, scientists may label an incremental benefit as “progress” or “promise.”35 To a nonscientist, such terms are understood quite differently as an indication that some mutually recognized goal (such as remedying a disease or condition) is within reach. Because the weight of the scientific evidence is interpreted differently, 32. Beginning in 1932, the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male” … 399 indigent Southern black men were recruited by health researchers who led them to believe they would receive free medical treatment for what they called “bad blood,” and were carefully monitored…. The men were not told they had syphilis, which can cause mental illness and death. And they were never treated for the disease…. 33. 34. 35. Alison Mitchell, Clinton Regrets ‘Clearly Racist’ U.S. Study, N.Y. TIMES, May 17, 1997, at A10. Jesse Gelsinger’s death in September of 1999 triggered a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) investigation of human gene therapy experiments conducted at the University of Pennsylvania because Mr. Gelsinger “died of multiple organ failure caused by a severe immune reaction to an infusion of corrective genes….” Sheryl Gay Stolberg, Gene Therapy Ordered Halted at University, N.Y. TIMES, Jan. 22, 2000, at A1. The investigation revealed “‘numerous serious deficiencies’ in ensuring patient safety during a clinical trial” and as a result the FDA put an end to the experiments. Id. Among these was the failure to inform Gelsinger’s family that one of the principal investigators held a major financial interest in the biotech firm that supplied the therapeutic vector. Patricia C. Kuszler, Curing Conflicts of Interest in Clinical Research: Impossible Dreams and Harsh Realities, 8 WIDENER L. SYMP. J. 115, 132 (2001). Recent clinical trials have shown that antidepressants “increase the risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior among children and adolescents.” Shankar Vedantam, Depression Drugs to Carry a Warning, WASH. POST, Oct. 16, 2004, at A1. Some were concerned that the child antidepressant/suicide connection was suppressed by the very federal agency that oversees drug safety because of ties to the pharmaceutical industry. See Greg Koski, FDA and the Life-Sciences Industry: Business as Usual?, HASTINGS CENTER REP., Sept.–Oct. 2004, at 24-25. Scientists define “progress” as growth in the collection of testable knowledge about the natural world. See Goldberg, supra note 30, at 1383. 533567609 642 3/9/2016 3:02 AM NEW ENGLAND LAW REVIEW [Vol. 39:635 there is a disconnect between it and the weight of the competing human interests. Scientists also are not free from employing non-scientific techniques such as rhetorical devices in advancing a particular position.36 Scientists who describe euphemistically rather than scientifically are not really advancing science; they are advancing a personal (or collective) philosophy. A resultant problem is the interference with an appropriate contextual analysis of the social costs as well as the social benefits needed to formulate a sound policy for such issues as human cloning and human embryonic stem cell research. Many scientists would draw the line, at least for now, between therapeutic cloning and reproductive cloning—approving only the former.37 But, as pointed out by O. Carter Snead, the only difference between a therapeutic clone and a reproductive clone is one of intent. If there is no substantive difference between them, what is to prevent a movement of the line by any scientist with access to the technology and human subjects? The line drawn in practice may be quite different than the line agreed upon in theory. A scientist’s control over both the decision and the experimentation itself is too burdensome on the rest of society. The temptation to devalue considerations that impede a scientific goal may repeatedly cloud judgment. Yet there would be no firewall of separation between decisionmaker and actor. There is also very little external legal pressure on scientists.38 And what if scientists are wrong?39 The consequences of 36. 37. 38. 39. See, e.g., June Mary Zekan Makdisi, Genetically Correct: The Political Use of Reproductive Terminology, 32 PEPP. L. REV. 1, 11-12 (2004) (discussing rhetorical adoption of the term “preembryo”); see also id. at 23-24 (rhetorical redefinition of “pregnancy” and “contraception”). See William P. Cheshire, Jr. et al., Stem Cell Research: Why Medicine Should Reject Human Cloning, 78 MAYO CLINIC PROC. 1010, 1012 (Aug. 2003) (rejecting the line), available at http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.com/pdf/7808/7808c2.pdf. See KUNICH, supra note 9, at 29-33 (describing laws in six states that had enacted legislation). Although there are a few states with laws limiting conduct, there is very little federal law that controls what manipulations scientists may do with human embryos, including those involved in stem cell research and cloning. See id. Federal regulations that prohibit endangering human embryos (including harvesting human embryonic stem cells) only apply to researchers using federal funds. It appears that the only federal law that applies is the Fertility Clinic Success Rate and Certification Act of 1992, which is primarily a reporting statute. See Pub. L. No. 102-493, 106 Stat. 3146 (codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. §§ 263a-1 to a-7 (2000)). Very recently scientists have been found to be wrong about the significance of nonprotein-coding sequences of the DNA molecule. John S. Mattick, The Hidden Genetic Program of Complex Organisms, SCI. AM., Oct. 2004, at 61 (noting that what was originally labeled as “junk” DNA is really complex non-protein-coding regulatory 533567609 3/9/2016 3:02 AM 2005]REGULATING HUMAN CLONING & STEM CELL RESEARCH 643 cloning and the exploitation of human embryonic stem cells have global effect. Thus, judgments about where the lines should be drawn appropriately lie outside the science arena. III. PUBLIC REPRESENTATIVES AS DECISION-MAKERS Perhaps public representatives are better equipped to make the broad decisions that ensure uniformity and appropriateness of conduct, drawing from science and other disciplines. A drawback, as pointed out by O. Carter. Snead, is that U.S. legislators are currently at an impasse because they do not agree on the underlying issue about the dignitary worth of nascent human life. If lawmakers within a nation do not agree, it should be no surprise to learn that lawmakers around the world do not as yet hold a singular view on the licitness of human cloning and human embryonic stem cell research.40 But if we recognize that we live in a global community and can no longer remain insular, we should work to formulate a global response. At the United Nations, world leaders have been working together since 2001 to find a common ground.41 Approximately twenty countries had expressed agreement with a Belgium treaty proposal that would draw a firm line at prohibiting reproductive cloning.42 Triple that number, or just 40. 41. 42. RNA matter, now identified as introns). Germany prohibits cloning and stem cell derivation. Jürgen Simon, Human Dignity as a Regulative Instrument for Human Genome Research, in ETHICS AND LAW IN BIOLOGICAL RESEARCH 35, 37, 40 (Cosimo Marco Mazzoni ed., Martinus Nijhoff Publishers 2002), available at http://www.bibliojuridica.org/libros/1/211/11.pdf (noting Germany’s protection of the human embryo’s dignity would prohibit its being sacrificed in the service of another). At the opposite pole are countries such as the United Kingdom, which regulates the industry through licensing. See Roger Brownsword, Bioethics Today, Bioethics Tomorrow: Stem Cell Research and the “Dignitarian Alliance,” 17 NOTRE DAME J.L. ETHICS & PUB. POL’Y 15, 33-37 (2003). SCNT cloning is now permitted as a matter of law. Genevieve Wilkinson, U.K. Grants First License to Clone Human Embryos for Research Purposes, BIOTECH WATCH (BNA), at 1 (Aug. 19, 2004) (noting that the U.K. granted its first therapeutic cloning license on Aug. 11, 2004). France has taken an intermediate position. New legislation permits scientists to legally use human embryonic stem cells imported from countries with on-going research projects, presumably because of the attenuation between the human embryos and the stem cell lines derived from them. Lawrence J. Speer, French Government Officially Authorizes Debut of Limited Embryonic Cell Research, BIOTECH WATCH (BNA), at 1 (Oct. 14, 2004) (referencing Decree No. 2004-1024, Relating to the Import of Embryonic Stem Cells for Research Purposes, Sept. 28, 2004). U.N. Legal Panel Remains Stalled in Effort to Ban Reproductive Cloning, 3 MED. RES. L. & POL’Y REP. (BNA) No. 21, at 827 (Nov. 3, 2004). Id. 533567609 644 3/9/2016 3:02 AM NEW ENGLAND LAW REVIEW [Vol. 39:635 over sixty countries, would have drawn the line earlier, banning all cloning as an affront to human dignity.43 In the end, neither proposal crystallized into a treaty. The Costa Rican ambassador, offering the super-majority position, attributes this to a procedural derailment.44 Rather than substituting another draft treaty, a declaration will be framed to prohibit “any attempts to create human life through cloning processes and any research intended to achieve that aim.”45 Whether SCNT (Somatic Cell Nuclear Transplantation) cloning for research purposes is outlawed by the declaration hinges on whether a biological or social definition of human life will be applied. But if human dignity is fundamental, then a social definition that is subject to movement based on politics is inadequate.46 Instead, an investigation of whether nascent human life must be accorded basic human dignity requires a search for objective truth rather than social expediency.47 Advocates of human cloning for research purposes and human embryonic stem cell research acknowledge that now we do not have an answer to this basic question.48 Until there are definitive answers, we must direct our attention to the temporary line. Do we push the frontiers of science in the arena of embryonic exploitation and ignore potentially crossing a line that disrespects human dignity? Or do we choose other avenues of exploration that we know do not cross that line? At this time it is premature to address the question of whether the line that could violate human dignity should be crossed for lack of an alternative to the information sought.49 Much has yet to be learned by 43. 44. 45. 46. 47. 48. 49. Id. (noting that human cloning was described by the resolution as “unethical, morally reproachable and contrary to due respect for the human person”). Ralph Lindeman, U.N. Negotiators Reject Anti-Cloning Treaty, Will Begin Work on Nonbinding Declaration, BIOTECH WATCH (BNA), Nov. 23, 2004. Id. (quoting the draft compromise). For now, supporters of both proposals are declaring optimism—one because the declaration would not prohibit all cloning, and the other because it did not endorse it. Id. See Lynch, supra note 19 (noting that acknowledgment of the existence of fundamental rights “presupposes the concept of truth” and that adherence to objective truth is our protection). See id. See, e.g., Ronald Chester, To Be, Be, Be … Not Just To Be: Legal and Social Implications of Cloning for Human Reproduction, 49 FLA. L. REV. 303, 319 (1997) (asserting that the answer is currently unknown and, perhaps, unknowable). See 42 U.S.C. § 289g(a), (b) (2000); 45 C.F.R. § 46.205(c) (2004) (no alternative means). The Omnibus Consolidated and Emergency Supplemental Appropriations Act extended to the protection of human embryos including ones derived by cloning. 1999 Pub. L. No. 105-277, § 511(a), 112 Stat. 2681-386. While Congressional prohibitions are currently based on funding, several unsuccessful attempts have been made to enact federal criminal law. See, e.g., Human Cloning Prohibition Act of 533567609 3/9/2016 3:02 AM 2005]REGULATING HUMAN CLONING & STEM CELL RESEARCH 645 pursuing means that do not invoke the human dignity issues. Preliminary successes indicate that frontiers may be pushed by experiments using human cord cells and “adult” stem cells.50 IV. ACCEPTING A TEMPORARY LINE BASED ON AN EMBRYO’S POTENTIAL ENTITLEMENT TO HUMAN DIGNITY A pragmatic reason exists for drawing the temporary line at restraint. If the line drawn errs on the side of permissiveness and the protections are later found to be harmful to human dignity, it will nonetheless be difficult to abandon them in the face of normalized use. How many of us prefer prescription medication over prescriptive behavioral change to get a favorable result? How many of us have given up personal transportation in favor of more environmentally friendly public transportation? How many readily give up our rich food or sweet tooth cravings, despite knowing of the harms? Substantively, if an embryo is worthy of human dignity based on its nature of being human, then on what legal basis may we terminate that life? A right to life is one of the fundamental values associated with human dignity.51 There are examples in our legal system where the basic endowments of human dignity are not removed absent proof of unworthiness, beyond the shadow of a doubt. For example, in criminal law, even a known rapist is allowed to go back out on the street. We can know that his release endangers other members of society and that he may commit another rape, yet we permit humans in society to bear this risk because freedom, even to a rapist, is fundamental. Deprivation of such a fundamental right requires more than a utilitarian balancing between those potentially harmed and the one whose rights would be deprived.52 50. 51. 52. 2002, S. 2439, 107th Cong. (2002); Human Cloning Prohibition Act of 2001, S. 1758, 107th Cong. (2001); Human Cloning Ban and Stem Cell Research Protection Act of 2003, S. 303, 108th Cong. (2003); Human Cloning Prohibition Act of 2001, H.R. 2505, 107th Cong. (2001) (engrossed); Human Cloning Prohibition Act of 2001, S. 1899, 107th Cong. (2002) (passed by the House on July 31, 2001); Human Cloning Prohibition Act of 2003, H.R. 534, 108th Cong. (2003) (engrossed). See, e.g., Emma Ross, Doctors Grow a Jaw for Transplant, MIAMI HERALD, Aug. 27, 2004, at 18A (reporting that a jaw bone was grown from marrow cells in muscle tissue); Researcher Points to Adipose Tissue as Plentiful Source of Adult Stem Cells, BIOTECH WATCH (BNA), Oct. 5, 2004 (reporting that stem cells from fat tissue may be used to treat heart disease, bones, spinal disease, and vascular diseases). See Simon, supra note 40, at 127 (noting that the “principle of human dignity guarantees the basic rights of life….”). See JOHN E. NOWAK ET AL., CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 460, 493-95 (3d ed. 1986) (emphasizing that freedom is so fundamental that procedural unfairness to a known 533567609 646 3/9/2016 3:02 AM NEW ENGLAND LAW REVIEW [Vol. 39:635 In addition to the general requirement that a high degree of proof is needed to ascertain unworthiness to basic human rights, there is a longstanding tradition of not permitting sacrificial killings absent imminent need. Take self-defense, for example. To justify the application of the privilege, one of two circumstances must exist: Either the one killed in self defense must have caused a threat of imminent serious harm, or the one seeking to use the privilege had a reasonable belief that the one killed posed a threat of imminent serious harm to himself.53 With respect to the justification of terminating nascent human life during stem cell research or research cloning, neither of the above conditions is present. Although imminent serious harm may exist (in the context of serious disease sought to be cured), the threat in no way is generated by the nascent human life that is killed. Nor does the threat disappear once the killing occurs.54 Suppose that the personal sacrifice is self-imposed for the benefit of another, as in the context of organ donation. Suppose further that organ donation is analogous to the donation of human embryos (including production and exploitation) based on some theory of substituted judgment and/or parental consent. Even then, there would be no justification in killing in order to achieve the donative purpose.55 A donor’s life may not be shortened by even one second to effect a donation, even if the donor was in the process of imminently dying, and even if it would be the only way that the designated donee could survive.56 It may be frustrating to cut short an avenue of exploration. But where basic human dignity is at stake, our law supports a conservative approach. We must not prematurely cut short the dialogue by allowing our insular selves to draw too permissive a line. In light of the global impact on the use of technologies that exploit the human embryo, a decision about whether it should be used must also be global. Until we are certain that a human embryo is objectively unworthy of human dignity, we must not exploit it, even for utilitarian benefit to other humans. 53. 54. 55. 56. criminal will effect his or her release). WAYNE R. LAFAVE & AUSTIN W. SCOTT, JR., CRIMINAL LAW 457-58 (2d ed. 1986). Except for some limited instances of cloning in the context of PGD, remedy is only a hope for some unidentified person from some future generation. See Jerry Menikoff, Doubts About Death: The Silence of the Institute of Medicine, 26 J.L. MED. & ETHICS 157, 162 (1998) (referencing the “dead donor” rule); see also UNIF. ANATOMICAL GIFT ACT § 8(b), 8A U.L.A. 58 (1987) (creating a separation between death and harvesting the donor’s organ). Menikoff, supra note 55, at 162.