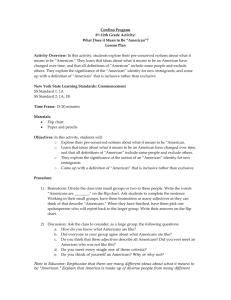

Spanish text

advertisement

The recent fast upsurge of immigrants in Spain and their employment patterns and occupational attainment This article provides an analysis of employment and occupational attainment of recent immigrants in Spain. We use data from the Spanish labour force surveys for the years between 2002 and 2007 and compare the probability of being employed versus unemployed and that of being active versus inactive among immigrants and native born Spaniards, using logistic regression models. We investigate, then, the quality of the occupation achieved by means of multinomial logistic regression models. We find evidence that immigrants are not at disadvantage in comparison with native-born Spaniards as regards the risk of unemployment. This is true after controlling for differences in socio-demographic characteristics between immigrants and Spaniards and, in particular, after accounting for the duration of the time spent in the labour market. On the other hand, a strong and persisting disadvantage (even controlling for socio-demographic characteristics and the time spent in the labour market) is documented for accessing skilled occupations. Important differences are also found among immigrant groups, being the Africans those most at risk of unemployment and East European those most likely to be employed in unskilled occupations. Keywords: labour market, migration, occupational attainment, Spain. Introduction In the last decade the amount of immigrants in Spain has spectacularly grown. In a few years, from being one of the European countries with the lowest share of immigrants, Spain heads the list of immigration receiving countries. The most recent estimates from the Spanish National Statistical office show that the percentage of foreigners in Spain 1 has increased from about one per cent in 1996 to ten per cent of the total population in 2007. This extremely fast and largely unexpected upsurge in immigration has attracted a growing body of research on immigrant situation in the labour market. Still, most of the studies have focused on specific immigrant communities (Escrivá 2003; Parella 2003; Ramírez 2003; Soriano 2006) or some specific dimensions of immigrants’ labour market participation such as their concentration in the unskilled occupations in the service sector (Bernardi and Garrido 2008). On the other hand those few studies that perform a more general analysis of immigrant situation in the labour market are based on data that get at most up to the year 2003 (Carrasco et al. 2003; Garrido and Toharia 2004; Amuedo-Dorantes and de la Rica 2006). Thus, a comprehensive study of recent immigrants’ situation in the labour marker in Spain is still missing. In this article we try to fill this gap. We focus on the integration of recent immigrants of various ethnic groups in the Spanish labour market comparing their chances of being employed and of achieving a skilled occupation with those of native-born Spaniards. Previous studies have shown that immigrants tend to have lower employment rates and to be concentrated in low level, unskilled occupations (Amuedo-Dorantes and de la Rica 2006). The main aim of this article is to study whether these disadvantages disappear or decrease once social and demographic characteristics (such as age, region of residence and education) are taken into account and as their residence lengthens. Our two key research questions are, thus, the following: 1) Do differences in the labour market situation between Spaniards and immigrants reduce once differences in socio-demographic characteristics are controlled for? 2) Do immigrants’ employment probability and chances of achieving a skilled occupation improve as time since migration goes by? 2 Immigration in Spain Spain has only recently witnessed significant migration inflows. Being negligible before the mid 1990s immigration has become sizeable by the end of last century and it boomed since 2000. The foreign-born population has, thus, increased about nine fold in a decade, rising from approximately 500,000 in 1995 to 4,500,000 in 2007. Between 1996 and 2001 the ethnic composition of the migration inflows was dominated by nationals from the European Union-15 and Morocco. Starting from 2000, immigration from Latin America (in particular from Ecuador and Colombia) has skyrocketed. Since 2004 arrivals from Bolivia and Eastern Europe (in particular Romania) also notably increased. Meanwhile, entries from UE15 and Morocco maintain a remarkable stability throughout the period. As a result, in 2007 immigrants count for about 10 per cent of total population and approximately two in five of them come from Latin America, about one in five from Eastern Europe (especially from Rumania), one in five from Africa (especially from Morocco), 15 per cent from EU15 and OECD countries and the rest (less than five per cent) from Asia (SLF 2007). Two characteristics of immigration should be highlighted. First, almost all people who entered Spain in the last years are labour immigrants. The amount of asylum claims submitted between 1995 and 2004 accounts for 1.5 per 1,000 habitants, while in countries such as Denmark and Germany the same figure is 14.1 and 10.5 per mill, respectively (UNHCR 2006, 225). Second, many non-EU15 immigrants entered Spain without a permit or remained in the country without a valid document after entering with a short term visa. Since 2000 all migrants, even illegal ones, who are enrolled in the administrative registers are granted health care, access to education and social services for their offspring. It has, thus, been argued that the generosity of the 3 welfare state might actually foster the entry of unauthorised immigrants who, then, wait for an amnesty that past experience suggests that earlier than later will come (Garrido 2005). Actually, an extraordinary process of regularization was granted in 1996 and two others in 2000 and 2005. In spite of these amnesties, the incidence of unauthorised/illegal immigrants is still high because the inflow of people not holding a proper permit of stay has not ceased thereafter (CES 2004). A comparison of the number of non-EU15 immigrants enrolled in the administrative registers and the total number of residence permits granted up to the beginning of 2007 suggests that about one in four of them is in an irregular position.1 Irregular immigrants work in the underground economy that, as in the Italian case, is very large and accounts for about 22 per cent of the GDP, according to recent estimates (Schneider 2005). In parallel with the upsurge in immigration, an impressive growth in employment has occurred. Between 1994 and 2007 Spain (altogether with Ireland) has recorded highest rate of job growth in Europe and the number of employed people has increased from 12 millions to 20 millions. Most of new jobs have been absorbed by low productivity sectors such as the construction and consumer service sectors where the presence of unqualified immigrant labour is also very high (European Commission 2007). With regard to changes in the occupational structure, the employment growth has come about with an expansion both at the top and the bottom of the occupational ladder (Bernardi and Garrido 2008). The occupations have most expanded are those that require a university degree (such as professionals and technicians) on one hand, and the unskilled jobs in the construction and consumer sector on the other hand. In the same years the proportion of persons employed in skilled occupations in manufacturing and in the service sector has slightly declined. Thus, there was plenty of opportunities for unqualified employment at the bottom of the occupational structure. At the same time, it 4 is likely that immigrants employed in unskilled jobs faced little opportunities of upward mobility since highly qualified non manual jobs are out of reach for them, while the demand for skilled manual jobs that are more accessible through on the job-training was relatively low. Data, variables and methods Our analysis draws on the Spanish Labour Force Survey and is focused on respondents aged between 16 and 64 years. An important feature of the Spanish LFS is that its sample is drawn on the base of administrative registers, so it includes also unauthorised immigrants, who have only access to low qualified and occasional jobs in the hidden economy, with almost no chances of upward mobility. It is, however, very likely that unauthorised immigrants are under-represented in the LFS data due to a special rule affecting the fieldwork.2 Unfortunately there is no information available that allow us to distinguish between authorised and unauthorised immigrants. When interpreting our findings it is therefore important to keep in mind that they also refer to unauthorised immigrants (even if under-represented in the data), so that they might portray a less favourable situation of immigrants in the Spanish labour market when compared to all the other studies that focus only on authorised immigrants. We merged all the quarterly data from the LFS for the years 2002 up to first three quarters of 2007 (the most recent data at the time of carrying out the analysis). Merging the LFS data for different years conveys two advantages. First of all, we can operate with a larger sample of immigrants. Our findings should accordingly be more robust, in particular when we perform separate analysis for different immigrant groups. Second, if one is interested in the effect of the time since migration on the progressive assimilation of immigrants in the labour market, a single cross section does not allow 5 distinguishing the effect of the years of residence from that of the cohort of immigration. As suggested by Borjas (1985), a cross-sectional estimation of the effect of time since migration is potentially biased by two factors. The first one is the process of return migration. If immigrants who do worst in the labour market are more likely to return back to their countries, the oldest cohorts of immigrants will over-represent the most successful immigrants and, thus, the effect of time since migration will be biased upward.3 The second problem arises if the average quality (in terms of unobserved characteristics) of successive cohorts of immigrants changes over time.4 If for whatever reason (changes in immigration policies, economic turbulence or political disturbance in sending countries) the quality of immigrants is higher in more recent cohorts, then the effect of time since migration is biased downward. The opposite is true if the quality of immigrants decreases among the most recently arrived cohorts. While we cannot control for the possible bias brought about by return migration, by using repeated cross-sections of the LFS at least we are able to identify the effect of time of residence in the country independently from that of cohort of immigration. As we mentioned, we consider two dimensions of the integration of immigrants: namely, their participation in the labour market and their chances of accessing skilled occupations. In our analysis, therefore, we use binary logistic regression models to study the probability of being active versus inactive and the probability of avoiding unemployment (only for those who are active). In order to study the access to different skilled occupations we estimate a multinomial logistic regression model based on the EGP class scheme collapsed in four categories:5 1) salariat (higher and lower service class and routine non manual higher grade occupations; classes I-II and IIIa); 2) petty bourgeoisie (small employers with and without employees; classes IVabc); 3) skilled 6 manual workers (classes V-VI) and finally 4) unskilled manual workers (classes VIIab and IIIb). All statistical models have been run separately for men and women. With regard to the independent variable, we use nationality to distinguish among immigrants the following groups: European Union (before enlargement) plus other OECD countries, Rumanian, Other Eastern European countries, Ecuador, Colombia, rest of Latin America, Morocco, rest of Africa and Asia (Garrido and Toharia 2004). In some analyses these nine groups are collapsed in five categories: EU15 plus other OECD countries, Eastern European, Latin Americans, African and Asian. In addition Spanish citizens are divided in three groups: Spanish people born in Spain, Spanish people born abroad and Spanish people with double nationality. The latter group refers to relatively recent immigrants mostly from Latin America who have achieved the Spanish nationality in the last years, while the majority of Spanish people born abroad has born in Europe (in particular in France and Germany) and has arrived to Spain before 1996 6. The other independent variables that we take into account are education, age, family status, region of residence and observation year. Education is coded according to the ISCED classification in six categories: illiteracy, primary education or less, lower secondary, upper secondary, vocational and tertiary education (reference category). Age is included with a five-fold classification: 16-24, 25-34, 35-44, 45-54 and 55-64. The variable “family status” of respondents distinguishes among married or cohabiting persons without children, married or cohabiting persons with children, single parents and other. In order to study potential differences in the demand of skilled labour we distinguish 5 groups of regions: Madrid, Catalonia, Northwest (including the Basque country, Navarra and La Rioja), the Mediterranean (Andalucía, Valencia, Murcia and the islands) and the rest of Spain. We also add dummies variables for the observation 7 years between 2002 and 2007 to control for the fact that we merge data for different years. In principle this variable allows us to investigate how the average immigrant position in the labour changed over time, net of all other individual characteristics. Finally, the models pertaining to immigrants include the variable “year since migration”, coded as a set of dummy variables in order to tackle with any potential nonmonotonic effects of the length of residence. Yearly dummies are defined for a time span that goes from less than one year to seven years passed since migration. An additional dummy for duration longer than seven years is also included. This last dummy identifies immigrants who have entered in the country many years ago. In order to minimize the possible bias of return migration and change in the quality of cohorts of immigrants discussed above, in interpreting the results we focus only on the first seven years since migration. In addition, we have defined the variable “time since completion of education” for native born Spaniards. Using the variable “time since migration” for immigrants and “time since completion of education” for the charter population we have, then, defined a third variable “potential time in the labour market”. This variable allows us to compare immigrants with native-born Spaniards considering the duration since their entrance into the labour market (Garrido and Toharia 2004). One can, then, compare the situation in the labour market of a Spaniard that has finished his education, for instance, five years ago, with that of an immigrant of similar characteristics that have arrived in Spain five years ago. Findings Descriptive evidence Among the potentially active population (aged between 16 and 64 years) both male and female immigrants tend to be notably younger than their native counterparts. Table 1 8 shows that male immigrants are between nine and six years younger on average than Spaniards and the same is true if one considers women. The exceptions are immigrants from EU15 and OECD countries and Spaniards born abroad or with a double nationality who have the same (or only slightly lower) average age as native-born Spaniards. One finds much more heterogeneity between Spaniards and immigrants and among immigrant groups when their level of education is considered. Broadly speaking, both male and female immigrants tend to be less represented among the highly educated (i.e. with a vocational or tertiary education) than native-born Spaniards.7 A deviant case from this general pattern are immigrants from the EU15 and other OECD countries and Eastern Europe, who hold a vocational or university education degree in considerably higher proportions than the charter population. On the other hand, immigrants from African countries show the worst educational record: illiterates are 18 percent among Moroccan women, 11 percent among other African women and 7 percent among African men (including those from Morocco). The pattern of educational attainment among immigrants from Latin America and Asia is somewhat in-between, with higher proportions at secondary education. The proportion of highly educated is higher among those coming from other Latin American countries (including Argentina, Chile and Mexico). Moreover the incidence of illiteracy among Asian is not negligible. Spaniards born abroad or those with a double nationality score closer to the charter population in terms of educational achievement. Gender specific patterns of employment for various immigrant groups compared to native-born Spaniards are presented in Table 1. As regards men, the employment rate does not differ much among immigrants and native Spaniards, while some differences are found in respect to inactivity and unemployment. Inactivity is less pronounced among all immigrant groups (with the exception of EU15 immigrants), which can be 9 explained by their age composition and the labour orientation of their migration. On the other hand, male immigrants have a higher risk of unemployment than native-born Spaniards. As regards women, patterns of employment show larger differences and the variation in the inactivity rate among immigrant groups and the charter population is huge. Female immigrants coming from Latin America and Eastern Europe have the lowest inactivity rate (between 15 to 20 percent), while those coming from Africa the highest, so that about one in two of them is inactive. Spanish born women (and also women coming from EU15 and Asia) lay somehow in-between these two extreme patterns, being about one in three of them inactive. Finally, Spanish women born abroad or with a double nationality tend to participate more in the labour market than native born ones, being only one in four of them inactive. As in the case of men, women of all immigrant groups have higher unemployment rate than native Spaniards. The disadvantage is extremely strong for women coming from Morocco and the other African countries. For these women the risk of unemployment is twice and thrice larger than that of native-born Spanish women, respectively. The large differences in unemployment and, above all, in inactivity rates bring about also notable variations in the employment rates among immigrants groups. For instance, while three Ecuadorian women out of four are employed, only one Moroccan woman out of four is so. [Here table 1] Table 2 presenting gender specific patterns of occupational attainment confirms that both male and female immigrants of all nationality groups are overwhelmingly concentrated in unskilled occupations (Carrasco et al. 2003; Amuedo-Dorantes and de 10 la Rica 2006). However, the proportion of immigrants from EU15 and OECD countries as well as for Spaniards born abroad employed in salariat is higher than that observed among native-born workers. Beside these relatively well-documented results, there are two other findings that should be highlighted. First, immigrant women are overrepresented in unskilled occupations and underrepresented in skilled manual occupations when compared to their fellow countrymen. Female immigrants are concentrated in unskilled occupations in consumer services (cleaning and caring of dependents) (Bernardi and Garrido 2008) and these occupations offer little opportunities of upward mobility through the accumulation of job-specific training or experience when compared to typically male-dominated occupations in manufacturing or even construction. This gender inequality in the risk of being employed in an unskilled occupation is most pronounced among those immigrant groups (Latin Americans and East Europeans) that show the highest female employment rate. Second, the proportion of small employers with or without employees is larger among immigrants coming from Asia and Africa (excluded Morocco). For these immigrant groups establishing small businesses (such as restaurants, corner shops and import-export small firms) seem to offer a way-out of the bottom of the occupational scale. [here Table 2] The descriptive findings do not take into account differences in the sociodemographic characteristics of the native-born and immigrant population. In order to control for a possible composition effect and in particular to investigate the role played by education for the integration in the labour market of immigrants and the native-born population, we now turn to multivariate analyses. 11 Employment patterns: findings of the multivariate analysis Table 3 and 4 present the estimates of a logistic regression of avoiding unemployment for active men.8 Table 3 shows how the coefficients that refer to the different immigrant groups compared to native-born Spanish vary once socio-demographic characteristics (age, education, family status, region of residence) are progressively included in the model. In this way we are able to test whether the higher risk of unemployment for male immigrants found in Table 1 is due to some of their characteristics. Model 1, thus, refers to the effect for each immigrant group compared to native-born Spaniards if only the nationality variable is included. The negative values for all immigrant groups confirm of course the descriptive findings. Then, stepwise, we have included age, education, family status, region of residence and a variable that measures time since migration for immigrants and time since finishing education for native-born Spaniards. [here Table 3] After controlling for the socio-demographic variables (age, education, region, family status) the penalties as regards avoiding unemployment decrease for Moroccans, Africans and Asians, whereas increase for people from Eastern Europe, EU15 and OECD countries and do not change for all the other immigrants. The inclusion of the variable education partly reduces the disadvantage for the lowest educated groups (Africans and Asians) and slightly increases it for more educated immigrants such as those coming from EU15, OECD and Eastern European countries. Therefore, overall the composition effects are limited. However, including the variable that proxies time spent in the labour market for immigrants and native-born Spaniards, the disadvantage 12 in comparison with Spaniards almost disappears for all immigrant groups and in the case of Ecuadorians, Romanians and Asians even became an advantage. These outcomes suggest that immigrants face a higher risk of unemployment as measured on a cross-sectional base, because many of them have just arrived into the country and have, thus, spent less time in the labour market. In this respect, one has to remember on the one hand that most of the immigration in Spain is very recent and on the other that most of native unemployed are youth living with their parents who can wait a long time for a job, while immigrants cannot rely on family support.9 Table 4 lets us to assess the different role that education and time since migration may play for avoiding unemployment for different groups of immigrants. For EU15 and OECD immigrants the educational returns in avoiding unemployment are pretty similar to those of native-born Spaniards:10 the higher the education, the higher the chances of being employed. To a lesser extent returns to education are also evident for Latin Americans, at least in terms of an advantage for university degree holders and a large penalisation for illiterates (who are, however, very few in this group of immigrants). By contrast, no educational returns are found for African men, while even negative returns concern Eastern European and Asian men as lower qualified people have a higher likelihood of being employed than university holders. With regard to the effects of time since migration, the general pattern is that as residence lengths, the likelihood of employment increases. This is generally true up to the third-fourth year of residence for all immigrant groups except for Europeans, for whom there is no clear effect of the time since migration, we can suppose because most of them entry Spain already holding a job offer. [Here table 4] 13 The same logic of analysis has then been employed to compare employment patterns of female immigrants and their counterpart native-born Spaniards. In this case, however, given the notable differences in the activity rate among immigrant groups we focused before on the probability of being active. Tables 5 and 6, thus, present the results of a logistic regression of the probability of being active, while Tables 7 and 8 show those of a logistic regression of the probability of avoiding unemployment for active women. Table 5 suggests that all immigrant women (with the exception of those coming from EU and OECD countries) have a higher propensity to participate in the labour market than the charter population. A substantial part of this higher propensity is due to an age composition effect (Spanish women are older on average) as documented by the reduction in the size of the coefficients for the various immigrant groups, once age is controlled for (model 2). Accordingly, after discounting the impact of education, the difference between immigrant groups with low educational achievement, such as Moroccan and Africa women, and the Spaniards increases once again. While there is no composition effect associated both to “family status” and “region of residence”, if one controls for the potential time in the labour market, the probability of being active for immigrants women compared with their native counterparts goes up substantially. [Here Table 5] In Table 6 we inspect whether education and time since migration play a different role for the various groups of immigrant women. For those coming from EU15 or OECD countries, the findings are very similar to native born Spanish women, so that higher educated women are much more likely to participate in the labour market than lower 14 educated ones. A somehow higher propensity to be active is associated to higher levels of education also among African and Eastern European women, but not for Latin Americans. With regard to the effect of time since migration, the general pattern is that the likelihood of being active increases up to the third/fourth year since migration and then it tends to level off. Again women from EU15 and OECD countries stand out, since in their case the propensity of being active is higher than for natives immediately after arrival, following an irregular pattern thereafter. In the case of Latin American women the increase in their advantage over time is less pronounced, suggesting that they manage to integrate faster (at least in terms of participation) in the labour market. Finally, we can remark that immigrant women living with their children are much more penalised as regards the labour participation than their native or EU15 counterparts. The reasons might be that, on one hand immigrant women face huge difficulties in conciliating childcare with paid employment because public care services in Spain are still relatively limited, private ones are too expensive and, contrary to natives, they cannot rely on the support of relatives11. But this result might also reflect cultural difference and a more traditional division of gender roles as it is probably the case for African mothers who are the least likely to participate in the labour market. Moreover, many immigrant mothers with small children have just arrived in Spain and have not yet worked in the country. They have, thus, to look for their first job and for a solution for the care of the children at the same time. This double complication might discourage a recently arrived immigrant woman with a small child to look for a job. [Here Table 6] 15 Tables 7 and 8 present results referring to the probability of avoiding unemployment for active women. Even without controlling for any socio-demographic characteristic, Table 7 suggests that there is little or no disadvantage associated to immigrant women, with the exception of women from Other Eastern European and Latin American countries and especially of those from Morocco and other African countries, who run a much higher risk of being unemployed when compared to native-born Spaniards. Large part of the penalties of African and Moroccan women are due to their relatively low prior education, as it is documented by the strong reduction in the coefficients that express their relative disadvantage once education is controlled for (model 3). Finally, if one also controls for the potential time in the labour market, only Moroccan and African women are sharply penalised as for the probability of avoiding unemployment, whereas all the other female immigrants turn out to be even advantaged when compared to their native-born counterparts. The reason of this advantage, which is quite larger than for male immigrants, may be the huge demand for female immigrants in sectors such as housekeeping and elderly caring. [Here Table 7] If one runs separate analysis for the probability of being employed for distinct immigrant groups, the findings follow the same pattern highlighted for the probability of being active. First of all, higher education strongly reduces the risk of being unemployed for women coming from the EU15 and OECD countries (see model 7, Table 8). In their case education functions exactly as for Spanish women (see model 6). Education also improves the chances of avoiding unemployment for Eastern European and African women, but it notably does not do so for Latin Americans and Asians, 16 among who women with secondary or even primary education have a higher probability of being employed than those holding a university degree. It is also notable that just among these two groups of immigrants the length of residence does not matter much in improving their employability. While for Eastern European and African women, the chances of being employed increases over time since migration, especially starting from the third year since migration, no change over time is found for Latin American and Asian women. The case of EU15 women looks more complex. It seems that their chances of being employed are high either immediately as they entered Spain (reflecting probably the fact that some of they came because of a job offer) or after some time since their arrival (showing a more gradual integration process in the labour market, maybe because they are more able to wait for a job). [Here Table 8] Occupational attainment: findings of the multivariate analysis Table 9 presents the results of a multinomial logistic regression of class attainment measured according to the EGP class scheme collapsed into four categories (being the unskilled occupations the reference category). Contrary to what was found for the probability of being employed (and also active for women), we do detect strong ethnic penalties in terms of occupational attainment. Controlling for all the standard sociodemographic characteristics and notably also for the potential time spent in the labour market, we still observe very large occupational disadvantage for all immigrants groups except those from the EU-15 and OECD (whose occupational attainment is basically similar or better than that of the charter population,) and Spaniards born abroad (whose penalty is generally rather limited). The Spaniards with a double nationality face a 17 higher disadvantage than Spaniards born abroad but still have much higher chances to reach a skilled occupation than the other immigrant groups. As we mentioned, the majority of Spaniards born abroad arrived to Spain before 1996 and are more likely to have had a chance to get a skilled occupation from on the on-set of their arrival, while Spaniards with a double nationality are relatively recent immigrants who have stayed in the country for a certain amount of time with a legal permit and have finally achieved the Spanish nationality. Of course, having had a legal permit and, now, the Spanish citizenship offer more opportunities of upward mobility to them when compared to other immigrants groups where the incidence of unauthorised immigrants is high. The other significant exception is that of Asians, who are more likely to be self-employed than employed in unskilled occupation when compared to native-born Spaniards. In general the ethnic disadvantage is largest for accessing the salariat class and partly reduces for self-employment and skilled manual occupations. Moreover, the ethnic penalties tend to be stronger for female immigrants, in particular as far as it concerns accessing skilled manual occupations. But, while in the case of the probability of being employed one could observe clearly differentiated patterns for distinct immigrant groups (being, for instance, Africans the most disadvantaged and Latin Americans the most advantaged), the ethnic penalty associated to avoiding unskilled occupations seems to be broad and common (with the mentioned exceptions) to all immigrants groups. [Here Table 9] The final question is to what extent foreign education is devaluated in the process of occupational attainment for immigrants and how the length of residence affects their 18 chances of accessing a skilled occupation. We have, thus, run separate analyses for the various immigrant groups to study how their education and the time since their migration affect their occupational attainment. We consider a simpler distinction between skilled (collapsing salariat, self-employment and skilled manual occupations) and unskilled occupations and estimate, as usual, separate logistic regression models for men and women, controlled for all the other independent variables. As regard men, Table 10 shows that for immigrants from EU15 and OECD countries returns to education are basically the same as for Spaniards, as they result from the sample including all the interviewed and so driven by natives. By contrast, for all other immigrant groups returns to education are lower than for the charter population. It is interesting to note that the lowest returns (as expressed by the smallest coefficients for the university degree holders when compared to other levels of education) are found among Eastern Europeans, who are the most educated immigrants. A poorer command of the receiving country’s language when compared to Latin Americans can probably explain the stronger devaluation of their educational credentials. For Asians there is no difference between tertiary and upper secondary education and the disadvantage associated to lower secondary education is relatively small. As we have already seen, Asians have higher chances to avoid unskilled occupations mostly as self-employed and, in that respect, formal education is a less crucial resource. [Here table 10] Looking at the parameters estimated for time since migration, the length of residence of course increases the likelihood of having access to a skilled occupation. The strong and 19 positive effect for long duration (over 8 years) can refer, however, to selected groups of immigrants who arrived many years ago. If one focuses, thus, on the first seven years since migration one finds a modest increase already in the second year since migration, that then levels off, for Latin Americans and a more progressive increase for Eastern Europeans and Africans, which becomes notable after five years since migration. It seems, thus, that for latter groups of immigrants the process of upward occupational mobility takes some more time than for Latin Americans. Language differences might, again, explain this result. It is important, however, to stress that the overall occupational attainment of Latin Americans is not much better than that of Eastern Europeans and Africans, as it resulted from Table 9. For EU15 and Asian immigrants there is no clear pattern regarding the effect of time of residence. Broadly speaking, that general pattern is also confirmed for women. There are, however, a few remarkable findings. First, as Table 6 showed, the ethnic penalty in accessing a skilled occupation is somehow lower for Moroccan and African women when compared to Latin Americans and Eastern Europeans. One should remember that Moroccan and African women have the lowest activity rate and run the higher risk of unemployment. Two processes might operate here. Either these women are able to wait and search longer for finally accessing a better job or/and there is a selection into employment based on some unobserved characteristics (for instance, command of Spanish language), so that those of them who are employed have also better chances to get a skilled job. Since in Table 11 for African women one finds a negative effect of time since migration on the probability of accessing a skilled occupation, the first of the two hypothesised process can be discarded. Given that only one in three of African and Moroccan women is employed (see Table 1), one might venture that their relatively better performance as far as occupational attainment is concerned, is mainly due to a 20 selection on some unobserved characteristics. Second, the highest educational returns (even higher than that of Spanish women whose effect dominates in model including all the interviewed) are observed for women from EU15 and OECD countries, while the lowest for those from Eastern Europe and Asia. Finally, with regard to the effect of time since migration, besides the negative effect found for African women, as in the case of men one finds that the likelihood of attaining a skilled occupation increases more over time for Eastern European immigrants than for Latin Americans. [Here table 11] Conclusions Amuedo-Dorantes and de la Rica (2006) conclude that male and female immigrants are significantly less likely to be employed than similarly skilled natives. Their study, however, is based on the 2001 census and does not include the numerous immigrants of the most recent years. Our results based on updated data are different. After controlling for the differences in the socio-demographic characteristics, immigrants turn out to be more likely to be employed than natives. Partial exceptions are African women and to a lesser extent African men, who are still at a higher risk of being unemployed. The key variables that account for the observed disadvantage of immigrants before controlling for their socio-demographic characteristic are education and the time spent in the labour market, while no composition effect is found for family status and region of residence. Part of the disadvantage in the employability of African women and men is, thus, due to their relatively low educational achievement. But most of the disadvantage is due to the fact that many immigrants have only very recently entered the country. Once the time in the labour market is taken into account, the “ethnic penalty” almost disappears and 21 becomes an “ethnic bonus” for Ecuadorians, Romanians and Asians. On the other hand, we find a persistent ethnic penalty for occupational attainment for almost all immigrant groups, even after controlling for all the other independent variables and the time spent in the labour market. In sum, one finds high levels of employment for immigrants, but with a very low occupational attainment that does not assimilate to that of natives as the time of residence in Spain goes by. Moreover, educational returns are considerably lower for immigrants (except for those from EU15 and OECD countries) when compared to natives. These findings should be interpreted on the backdrop of three characteristics of immigration in Spain. First, almost all immigrants are labour immigrants and, therefore, are willing to enter the labour market as soon as possible even if that implies a low qualified occupation. Second, unauthorised immigrants who represent a substantial segment of overall immigrants are included in our analysis, although they are likely to be under-represented. Still, the chances to accessing skilled occupations are almost null for unauthorised immigrants. Third, Spanish economy is largely biased towards low productivity sectors with huge demand for elementary occupations and little demand for skilled manual labour and thus fewer opportunities of upward mobility for immigrants. On the other hand, our analysis has highlighted important differences among immigrant groups. EU15 and OECD are like Spaniards with respect to their observed educational returns. Latin Americans (in particular women) have the highest chances of being employed, but do not progress in terms of occupational attainment, maybe because they are clustered in unskilled occupations in personal services that offer no chances of upward mobility. Africans are those who suffer the highest disadvantage to find a job, but, probably because they are selected on some unobserved characteristics 22 (language and previous acquired skills), they do not so bad in terms of occupational achievement. By contrast, the worst educational returns to education in terms of occupational attainment are found for Eastern Europeans who are the most educated. This result may reflect the fact that they do not command Spanish at their arrival in Spain, when compared to Latin Americans and to a lower extent to Moroccans. Finally, Asian immigrants manage to avoid unskilled occupation mainly via self-employment. To conclude, although the skill-barrier proves very difficult to be overcome by all non-EU15 immigrants, the processes underlying their disadvantage in occupational attainment are likely to be different. In this article the primary focus has been on the comparison between natives and recent immigrants, so differences among immigrants have moved to a certain extent to the background. Future research should, accordingly, concentrate on non-EU15 immigrant groups and deepen the analysis on the processes that account for their different labour market integration. 1. An unauthorised immigrant can enrol quite easily in the administrative registers. It is enough to present a rental contract or a bill (gas, electricity, telephone) issued to him/her or a letter by someone who is enrolled in the administrative registers and declares that the unauthorised immigrant lives with him/her. The incentives to enrol in the administrative registers are great because registration gives access to health care and social services. Moreover, as past regularizations required having been enrolled in those registers for a certain time, the experience advises a recent illegal immigrant that enrolling in the administrative registers means also acquiring the future right to avail him/herself of the next regularization drive. 2. The rule is that people who have been selected in the sample but are not sure to live in the same place within a year time are not interviewed. The sample of the LFS includes a rotating panel and the “one year expected stability” rule serves to facilitate the tracking of the people in the panel design. It seems reasonable to expect that unauthorised immigrants are less settled and more mobile than authorised ones and, thus, less likely to be interviewed. 3. As it is often noted, the direction of the bias produced by return migration is not obvious (AmuedoDorantes and de la Rica 2006). It might be that those who face most difficulties in integrating in the 23 labour market are more likely to return to their country of origin. Or the most successful immigrants might choose to go back to their country after saving enough money. In the case of countries with very recent immigration such as Spain, the first process is more likely to occur, since the time span for saving money and successful return to the origin country is very short (Borjas 1996). 4. One might argue that since most of the immigration in Spain has occurred in the last decade, the possible biased induced by changes in the unobservable quality of the successive cohorts of immigrant should not be very severe. As a matter of fact there are notable differences in the observable quality (as measured by their level of education) of the various nationality groups (see Table 1 below), but the average quality (again measured in terms of the level of education) does not vary much over cohorts of immigrants. Results not shown but available upon request. 5. We report among brackets the coding and typical labels of the EGP classes (Erikson and Goldthorpe 1992). 6. According to the data from the Law Ministry, more than 60,000 immigrants achieved the Spanish nationality in 2006. In order to gain the right to the Spanish nationality one immigrant has to have lived in the country with a legal permit for a certain period of time (for instance two years for Latin American immigrants), or having married with a Spanish citizen or having at least two Spanish grandparents. On the other hand, about 80 per cent the Spanish born abroad have been living in Spain for more than 10 years (SFL 2007). 7. Previous research has shown that both tertiary education and vocational education strongly increase the chances of avoiding unemployment and that of accessing a skilled occupation also when compared to upper general secondary education (Martinez et al. 2006). 8. The results for the probability of being active are not shown for space limitation, but they are available upon request. The findings are dominated by effect of age, since Spaniards are older on average than immigrants. Once the variable age is introduced, the differences by nationality decrease sensibly. 9. Somebody can remark that the potential time in the labour marker correlates with age and that the results might be biased by the fact that immigrants are quite younger than native-born Spanish. To control for this correlation we have also estimated the model selecting only people aged 20 to 44 and we have found that the ethnic disadvantage reduces further if the comparison concerns younger age groups only (results available on request). 24 10. The coefficients for education in model 6 of Table 4 are driven by natives who are the great bulk of interviewed in the overall sample. 11. One should note that since income is one of the key criteria taken into account to rank access to public care services, immigrants who are usually employed in low paid jobs and often with undeclared wages in the hidden economy tend to have more chances to get access in public kindergarten for their children than native Spaniards. References Amuedo-Dorantes, C. and de la Rica, S. (2006) ‘Labour market assimilation of recent immigrants in Spain’, IZA discussion paper 2104, April. Bernardi, F. and Garrido, L. (2008) ‘Is there a new service proletariat? Post-industrial Employment Growth and Social Inequality in Spain’, European Sociological Review, 24(3), forthcoming. Borjas, G. J. (1985) ‘Assimilation, Changes in Cohort Quality, and the Earnings of Immigrants’, Journal of Labor Economics, 3(4): 463-489. Borjas, G. J., Bratsberg, B. (1996) ‘Who leaves? The outmigration of the foreign-born’, The Review of Economics and Statistics, 78(1): 165-176. Carrasco, R. et al. (2003) ‘Mercado de trabajo e inmigración’ in Izquierdo, A.(dir.) ‘Mercado de trabajo y protección social en España’. Madrid: CES, 183-248. CES (Consejo Económico y Social) (2004) ‘La Inmigración y el Mercado de trabajo en España’ Colección Informes CES, Informe 2/2004. Escrivá Chordá, Á. (2003) ‘Inmigrantes peruanas en España. Conquistando el espacio laboral extradoméstico’, Revista Internacional de Sociología, 36:59-83. Erikson, R. and Goldthorpe, J.H. (1992) The Constant Flux: A Study of Class Mobility in Industrial Societies. Oxford:Clarendon. 25 European Commission (2007), Employment in Europe, Luxembourg: European Communities. Garrido, L. (2005) ‘La inmigración en España’ in J.J. González y M. Requena (eds.) Tres décadas de cambio social en España. Madrid: Alianza. Garrido, L. and Toharia, L. (2004) ‘La situación laboral de los españoles y los extranjeros según la Encuesta de Población Activa’, Revista Economistas 99: 74-88. Martínez-Pastor, J. I.; Bernardi, F. and Garrido, L. (2006) ‘Employment opportunities at entry into the labor market in Spain since the mid-1970s’. Working Paper No. 8. University of Bamberg. Parella I Rubio, S. (2003) ‘La inserción laboral de la mujer inmigrante en los servicios de proximidad en Cataluña’, Revista Internacional de Sociología, 36: 85-113. Ramírez Goicoechea, E. (2003) ‘La comunidad polaca en España. Un colectivo particular’, REIS, 102: 63-92. Schneider, F. (2005) ‘Shadow Economies around the World: What Do We Really Know?’, Journal of Political Economy, 23(1): 598-642. Soriano Miras, R. M. (2006) ‘La inmigración femenina marroquí y su asentamiento en España. Un estudio desde la Grounded Theory’, Revista Internacional de Sociología, 43: 169-191. SLF (2007) Spanish Labour Force Survey, Madrid: INE. UNHCR (2006) The State of the World's Refugees. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 26