A full transcript of the event

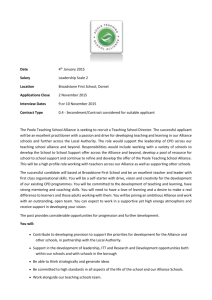

advertisement