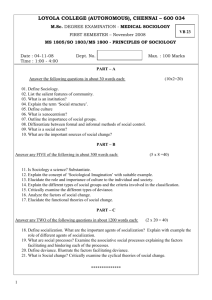

Student Study Guide

advertisement