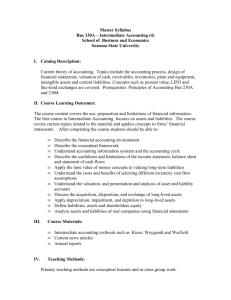

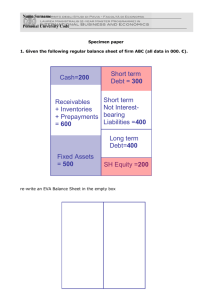

CHAPTER 2 – Notes to financial statements as the important source

advertisement