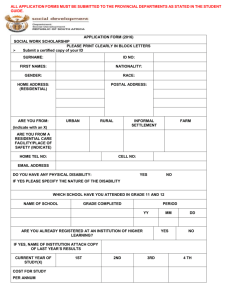

219Kb Word doc - University of the Witwatersrand

advertisement