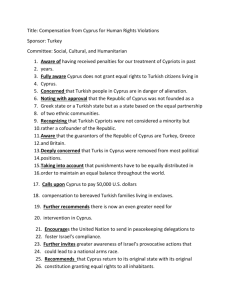

Cyprus : Reunification or Partition?

advertisement