1 - AmCham Egypt

advertisement

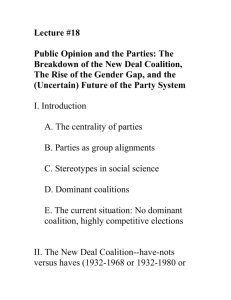

BUILDING AN EGYPTIAN SERVICES COALITION This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by the USAID-funded TAPR II project in collaboration with the USAID-funded Trade Related Assistance Center (TRAC) at the American Chamber of Commerce in Egypt. BUILDING AN EGYPTIAN SERVICES COALITION TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE FOR POLICY REFORM II CONTRACT NUMBER: 263-C-00-05-00063-00 BEARINGPOINT, INC. USAID/EGYPT POLICY AND PRIVATE SECTOR OFFICE AUTHORS: VICTORIA WAITE (NATHAN ASSOCIATES) RICHARD SELF SO 16 DISCLAIMER: The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Contents Executive Summary v Introduction 1 Coalition Objectives 3 Value-added aspects for the private sector 3 Value-added aspects for the Government of Egypt 4 Coalition Activities 7 Manage relationships among the membership and with public officials 7 Establish subgroups to address specific issues and sectors 7 Build knowledge and understanding on services issues 8 Develop trade barriers lists 8 Collaborate with global services organizations 8 Challenges in the Creation of a Services Coalition 9 Addressing procedural challenges 9 Competing business associations 10 Tackling issues related to sensitive sectors 10 Assuring broad participation in Government consultations 10 Services Coalitions Worldwide 13 New association or entity 13 Partnership with an existing entity 14 Combined Government and Private Sector Initiative 15 Donor Initiated 16 Establishing a Services Coalition in Egypt Next steps References 17 19 21 Executive Summary As trade in services continue to exhibit steady growth rates in the global economy, more and more developing countries are realizing the important role the services sectors play in their economic development and are including services to further deepen their economic integration into the world marketplace. This is evident by the increasing number of developing countries currently negotiating binding services provisions in regional and bilateral trade agreements, and includes, inter alia, European-Mediterranean Partnership Agreement, COMESA, GAFTA, SADC, and ASEAN. While trade negotiations are Government to Government proceedings, the private sector also has a considerable stake in the development and expansion of the services sector, particularly as the implications of trade agreements can have both direct and indirect impact across the economy. In several developing and developed countries, private sector services firms have chosen to formalize their services sector advocacy efforts by establishing umbrella associations dedicated to advancing the services sector’s trade-related interests both domestically and abroad. Currently, Egypt finds itself in a situation in which comprehensive private sector input on trade in services issues does not exist. The services sector in Egypt accounts for large percentages of its GDP and overall workforce, in addition to spanning a wide range of services, from tourism to port facilities, from telecommunications to construction services, and from Arabic movie and television programming to financial services, among others. The Government is involved in multiple trade negotiations that encompass services components, and the private sector is in the best position to advise the Government on issues affecting their sector. Moreover, Egyptian service providers have a stake in the outcome of trade negotiations and other policies affecting their sectors. In order to organize their efforts as an industry group, the Egyptian services sector is in the process of developing a plan to establish an Egyptian services coalition. The objective of the Egyptian services coalition is twofold: 1) for trade negotiation purposes; and 2) for internal competitiveness purposes and regulatory reform. The private sector needs to better communicate its trade negotiation and export market interests to Government officials and can provide analysis and input on existing policies that do not meet the needs of the services sector, identify policies that inhibit growth or serve as obstacles to exporting, formulate the right policies to enhance services trade, and help facilitate better access to knowledge and information on services. In addition, the Egyptian services coalition would work to bridge the internal gap between services providers through an internal dialogue; push for regulatory reform in key sectors, while developing relationships with relevant regulatory bodies and Syndicates to facilitate dialogue among all stakeholders; and strongly encourage the Government to improve services data. Although services coalitions tend to focus on activities related to trade negotiations or export market interests, they also serve to accomplish a number of important initiatives at home. For VI BUILDING AN EGYPTIAN SERVICES COALITION example, initial activities of the Egyptian services coalition could consist of advocating for regulatory reform, including the publication of all regulations affecting services sectors; pushing for improved services data, including through sectoral surveys and improved data collection by the Central Bank and CAPMAS; raising awareness of services sectors and issues constraining their competitiveness; guiding Government efforts to attract investment in specific sectors; and making services competitiveness the center of the country’s competitiveness drive. There are several challenges that Egypt will likely face as they move forward in establishing a unified forum for its service industries. First, it must find a capable, dynamic leader to act as the Chairperson of the entity. This is extremely important as the Chairperson has the capability of raising the services coalition to a visible stature both within the Government and in the private sector. The coalition will need to engage in an aggressive public awareness campaign that highlights the very specific objectives of the coalition, which will primarily focus on macro level trade in services issues, and therefore, will not impede upon the territory of sector specific trade associations. In fact, in many countries, sector specific trade associations can play an active role in the umbrella services coalition and reach out to an even broader group of stakeholders. In recent years, a number of developing countries have formed their own services coalitions from which Egypt can learn from, and there are several developed country services coalitions as well. Typically, services coalitions tend to develop into a brand new association as in the United States; as part of an existing association as is the experience in Hong Kong, Chile, and Malaysia; or in collaboration with the Government as is the case in Trinidad and Tobago and Barbados. And in Uganda, the Uganda Services Exporter’s Association was initiated by the donor community. Each example can provide valuable information for Egypt to consider as it moves forward in realizing its services coalition. Finally, Egypt already has a critical mass of interested services sectors. It should not worry about the structure at this point, but it needs to take advantage of this current momentum and organize activities for potential membership to demonstrate the strength and utility of a services coalition. At the same time, a concrete proposal should be presented to the Minister of Trade and Industry to solicit Government support and buy-in, which is also a critical aspect of ensuring a successful outcome and future work program for the services coalition. Introduction In July 2006 at a one-day Trade Related Assistance Center (TRAC) seminar entitled “Trade in Services: Egypt’s Experiences”, the group recommended the creation of an Egyptian Coalition of Service Industries with the objective to develop a private sector led industry group dedicated to addressing trade in services issues in Egypt. This short paper 1) outlines the primary objectives of a services coalition; 2) lists the types of activities that could be promulgated on a day-to-day basis; 3) addresses challenges to establishing such an entity, and particularly in Egypt; 4) describes developing country experiences in organizing services coalitions; and 5) concludes with a general elements to establishing a services coalition. The growing importance of trade in services cannot be ignored. In 2005, global exports of commercial services1 totaled $2.42 trillion, registering a 10 percent annual increase from $2.19 trillion in 2004. Services were first introduced in trade negotiations at the launch of the GATT Uruguay Round in 1986. Such an initiative was the direct result of service industry organization and pressure from groups in the United States and Europe. Services are now part of almost every multilateral, regional, and bilateral trade negotiation. With a population of approximately 70 million, services in the Egyptian economy accounted for over 50 percent of the GDP and 54 percent of the workforce in 2004. Moreover, services are being traded on a larger scale, propelled by modern technologies, such as the Internet, and more open foreign investment regimes. Thus, the stakes are huge for Egyptian services providers, many of whom have strategic export interests or otherwise face increasing competition from abroad. For all of the private sector entities devoted to agriculture and manufactures, there is no group that focuses solely on trade-related issues affecting the services sectors in Egypt. Egyptian service providers need to build upon the current momentum generated by the TRAC-organized roundtable discussions in January and April and move forward to establish an Egyptian services coalition. Egypt is an active member in the World Trade Organization (WTO), representing the developing country perspective, and has become a demandeur in the Doha multilateral negotiations. Concurrently, Egypt is expanding its own trade policy agenda to include regional trade in services negotiations in COMESA and GAFTA, and the European Union Economic Partnership Agreement. It is imperative that the services sector organize itself in a manner that ensures its ability to uphold its own interests in Egypt while promoting its wellbeing in other markets. The services sector must understand its rights and obligations so that it can take advantage of the very trade agreements its Government is negotiating on its 1 Commercial services are defined as transportation, travel, and other commercial services. Other commercial services include: communication services, construction services, insurance services, financial services, computer and information services, royalties and license fees, other business services, and personal, cultural, and recreational services. WTO, 2006. 2 BUILDING AN EGYPTIAN SERVICES COALITION behalf. At the same time, a services coalition presents a crucial opportunity for the private sector to build its own capacity and knowledge on trade in services issues by engaging in activities that examine specific aspects of the services sector in the Egyptian economy while enhancing public awareness in general. In the following sections, coalition objectives, potential activities, and challenges will be addressed, followed by a discussion of examples of services coalition worldwide, and concluding with key elements to creating a services coalition in Egypt. Coalition Objectives A service coalition (or coalition of service industries) is an umbrella organization that brings service providers and associations together to represent a collective voice on, among other things, commercial policies and export promotion issues. While goals can vary from country to country, one primary objective of a services coalition is to organize the private sector so that it can better communicate its trade negotiating and export market interests to Government officials. By identifying and defining issues of common interest among members and working together through a unified voice and consensus building, a services coalition can have an impact on how trade issues are addressed within the Government and its regulatory agencies. Other important objectives include: Advocacy. Services coalitions advocate on behalf of their membership, especially when there is a need to advise the government about 1) existing policies that do not meet the needs of the services sector; 2) policies that inhibit growth or serve as obstacles to exporting; and 3) formulating the right policies to enhance services trade. Reaching out with a harmonized voice is an effective way to influence policy decisions and to better inform the government, the private sector, NGO’s, and civil society of the types of issues that concern the coalition. Governments are more likely to respond to a united voice that represents a dynamic and cross cutting section of its economy, than a single company or an individual. In addition, services coalitions have the capability to develop and maintain relationships at different levels in Government Ministries (e.g., Minister, Undersecretaries, Department Managers, etc.), which is key to facilitating successful private-public sector communication. Better access to services sector knowledge and information. Services coalitions are resources of information for their membership. They establish internal (i.e., membership-oriented) and external (other services coalitions) networks that communicate and share information about what is occurring domestically and internationally. This is particularly important in trade negotiations, where there are a multitude of services issues over which the industry has a strategic interest. Sharing knowledge and information will benefit coalition members as a whole. For example, members can assemble data on barriers they face when operating in other markets that negatively impact the ability to provide inexpensive, efficient, and quality services to international clients. VALUE-ADDED ASPECTS FOR THE PRIVATE SECTOR Service providers are busy running the day-to-day business and may not be aware of the trade-related policies affecting their sectors, nor can they always dedicate the time to research and monitor the activities of the government as it formulates negotiating positions that will affect the welfare of Egypt’s services industries. A services coalition can provide a focal point 4 BUILDING AN EGYPTIAN SERVICES COALITION for identifying any problems the industry may have with the Government’s positions and proposals affecting services. It can form specific responses to the Government that will improve or otherwise facilitate the interests of the industry. It also serves as a convenient, central point for the Ministry of Trade and Industry (MTI) to consult with the services industries as it encounters new issues in negotiating services provisions with other countries. The coalition management would assume the role of coordinating with the affected services companies and forming an initiative based on the more informed views of persons and companies who are experienced in doing business under specific regulatory regimes. In the final analysis, no government can effectively formulate a negotiating agenda for a set of sectors as diverse and inherently complicated as the services sectors without the practical knowledge and experience that services providers themselves bring to the equation. It is the services providers who fully understand the most egregious regulatory restrictions and who are in the best position to help set the Government’s negotiating priorities. VALUE-ADDED ASPECTS FOR THE GOVERNMENT OF EGYPT Although a services coalition initiative should be organized and managed by the private sector, the value that such an organization can bring to the government is quite significant, particularly for MTI. MTI is responsible for formulating, negotiating, and implementing international trade policy, including trade negotiations covering a broad range of issues, inter alia, manufactured goods, agricultural products, textiles and apparel, services, intellectual property rights, and technical barriers to trade. It is impossible for trade negotiators to be technical experts in each of the areas of negotiation. They must rely on colleagues in other government Ministries, regulatory agencies as well as the private sector for input and knowledge. With the services sector, it is even more complicated because services encompass a wide range of economic activities, differing forms and degrees of regulation (i.e., virtually none to heavily regulated), and an operating climate where barriers are engrained in legal and regulatory measures. Regulatory responsibility is borne by numerous ministries and regulatory bodies. Inevitably, different regulatory measures and philosophies govern the services sectors, in contrast to goods, which are usually governed by a single instrument of protection, the tariff, to address foreign entry at the border. Egypt is engaged in a number of trade negotiations, nearly all of which have or will have provisions covering the services sectors. To accurately represent Egypt’s services sectors, MTI must engage those who are in the best position to know the intricacies of measures affecting services sector, in particular those government laws and regulations that may be the object of requests by trading partners demanding their removal or change. To manage these issues, the negotiators ordinarily rely on two sources: the regulatory body or Ministry responsible at the government level, and the private sector itself. While the government regulatory body or Ministry is able to provide expertise and knowledge on domestic laws, regulations, decrees, measures, etc. affecting the relevant services sectors, the private sector can advise on how domestic commercial policies (good and bad) affect their businesses as well as inform MTI about trade barriers that act as impediments in important export markets. In addition, the services coalition (i.e., private sector) can interact with independent regulatory bodies (e.g., Syndicates) and/or other entities to access the right individuals within an organization. Inevitably, there are differences of opinion between trade negotiators and ministries and regulators responsible for a service sector, especially where the regulator fears that its own prerogatives are being undermined by a trade negotiation. (In some instances, such as financial services, the Finance Ministry may have the negotiating lead.) The private COALITION OBJECTIVES 5 sector can help bridge these differences, using its frequent relationship with the regulatory body to point out the larger objectives of commercial policy that are at stake in a negotiation, and the overall welfare of the service itself. Or, they can help explain why the position of the regulator is important to preserve in such a negotiation. Coalition Activities There is a wide range of activities that services coalitions can engage in to meet the needs of their membership. The following illustrative list includes management, public outreach, information dissemination, and other activities. MANAGE RELATIONSHIPS AMONG THE MEMBERSHIP AND WITH PUBLIC OFFICIALS For all of the economic diversity in the services sectors, there are common points of view that can and should be established. For instance, supporting a transparent system of publishing regulations is something that each member can support. Building collective positions facilitates stronger relationships among the membership, and this helps to establish common priorities and strategies for the coalition. The coalition staff, as well as representatives of individual members, is responsible for reaching out to their constituency to facilitate dialogue and build consensus on official coalition position papers and letters. It is also important that they disseminate information to keep members abreast of current events in the services sector. Senior management will be essential to connecting with members and helping to develop ideas that will form the foundation of the coalition’s work as well as to hold meetings, where appropriate, with more senior government officials on particular issues. Unavoidably, there will be differences of opinion about liberalization in a particular sector. It is important, however, for the membership to understand these differences so that they can be managed when presenting a position to the Government. In addition to managing relationships with members, a critical responsibility of a services coalition is to maintain relationships with public officials in relevant Ministries and regulatory agencies, facilitating better coordination and dialogue on issues that involve MTI, other government ministries and regulatory bodies, and coalition members. In several cases, it is the coalition that brings these two groups together. For example, when a trade negotiator needs input from the private sector, he/she can call the services coalition and request a meeting with its membership. This is also a more efficient way of conducting business as it reaches a broad range of private sector stakeholders, or when necessary, to gain the position of representatives of an individual service sector. This also helps to guarantee a certain amount of policy ownership by both parties. ESTABLISH SUBGROUPS TO ADDRESS SPECIFIC ISSUES AND SECTORS Services coalitions often formulate working groups according to a specific sector (e.g., a Financial Services Working Group or Legal Services Working Group) or a horizontal/cross- 8 BUILDING AN EGYPTIAN SERVICES COALITION cutting topic (e.g., a Mode 42 Working Group or GAFTA Negotiations Working Group) issues. Meetings are organized to discuss and define the issue by the industry (i.e., members) experts, develop consensus driven positions, and devise a strategy for advocacy. Working groups are key to facilitating the work of the coalition because they organize the topics and allow members with particular interests to focus their time and energy. In addition to meetings, emails are just as important to keep the Working Group members updated on issues, and can also help facilitate the consensus building process. BUILD KNOWLEDGE AND UNDERSTANDING ON SERVICES ISSUES The concept of trading a service is still relatively new to the public, especially the linkages to trade agreements. A coalition can focus outreach to academia, policy experts, think tanks, media, and similar outlets so that there is a broader understanding in the public for the role these sectors play in economic growth, development, and in international relations. Joint initiatives can be undertaken to conduct a program of research in think tanks or academic institutions that will explore in greater depth the role these sectors play in the Egyptian economy. These efforts become tools to public outreach, where eminent persons and journalists address the important role that services plays in Egypt’s economy and its role in the international economy. DEVELOP TRADE BARRIERS LISTS Trade negotiators need help in having a full inventory of trade barriers their industries face in doing business abroad. The coalition can help form this list and present foreign trade barriers with a sufficient amount of detail (including foreign regulatory provisions) so that negotiators are comfortable with putting forward their list of problems to counterparts in other countries. Industry cannot count on the Government to have all of the information it needs to negotiate away foreign obstacles to doing business. It must take the initiative to prepare all of the necessary information. A coalition can serve as a point of coordination and assistance in putting such an inventory together. COLLABORATE WITH GLOBAL SERVICES ORGANIZATIONS There are several services coalitions around the world and many of them work in partnership to develop statements and press releases that reinforce their mutual objectives. For example, ten different services coalitions released a joint press statement in February 2007 calling for progress in services to be made in the Doha Round of trade negotiations if the overall outcome is to receive the support of the Global Services Coalition. Another example of collaboration is that the Global Services Network tends to organize services related activities in Geneva and at WTO Ministerials to demonstrate and reiterate the importance of services sector in the global economy and to meet with key officials for updates on negotiations. Mode 4 is a term used in the WTO’s General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) that describes the supply of a service through the presence of natural persons, i.e., when the service provider travels to the host country to deliver the service, or in other words, the movement of labor. 2 Challenges in the Creation of a Services Coalition Establishing a services coalition is never a simple task. For developing countries, it is even more difficult because of the number of procedural and substantive challenges it must first overcome. It is easy to talk to services providers to gauge their interest and discuss the value of forming such an entity. The more daunting task for developing countries is to 1) discover a way to build the financial soundness of a services entity as stakeholders tend to have limited access to monetary funds; 2) build awareness in an economy that has a host of other worries, and may not fully understand nor appreciate the role of the services sector in their economy; and 3) manage issues to reach and address the members concerns in a way that every firm or association recognizes the utility of the coalition. ADDRESSING PROCEDURAL CHALLENGES Initial start-up can pose the biggest obstacle as proponents must address decisions related to the structural formation, financial sustainability, and competent leadership. First, there must be a cross-section of companies who share a common interest in furthering their position in other markets and protecting their own interests at home. This includes a willingness to offer the time of company officials to participate in meetings that address these issues and to form creative approaches that represent the common needs of the participating industries. This includes, of course, an interest to engage the Government on these issues, which is not always a simple task. It also requires some patience, as some issues of greater strategic interest to other participants can become a large part of the agenda. Second, an effective coalition needs to have a strong Chairman; someone with stature and a commitment to the effort so that the membership has direction, zeal, and a collaborative environment. Third, funding the coalition may also be an issue; whether to hire full or part-time staff or otherwise pay for the administrative expenses associated with holding meetings and publishing positions. There is no question that Egypt needs to organize its services sectors, but it should do so while taking into account its unique socioeconomic culture. Sustainability, both at an activity level and a financial level, will be an issue if careful attention is not paid to the eventual structural organization of the services entity and its ability to meet the needs of all of its membership. As Egyptian services stakeholders begin to identify and prioritize their needs, they should also be able to determine to what degree services related issues are important. Developing an organizational structure can take place over time, allowing the services coalition to evolve with its membership and cross-cutting and sectoral issues. 10 BUILDING AN EGYPTIAN SERVICES COALITION COMPETING BUSINESS ASSOCIATIONS Often times business associations are more broadly focused (e.g., Chambers of Commerce or the Federation of Egyptian Industries) or concentrate on sector specific issues (e.g., tourism, banking, or telecommunications). However, these types of business/trade associations and an umbrella services coalition need not be mutually exclusive. In fact, almost all services coalitions in other countries include sector specific business/trade associations in their membership structure, which can expand the outreach to a broader audience. Respective relationships and roles of associations must inevitably be reconciled, but what is clear is that there is no business association in Egypt that is devoted exclusively to a cross-section of services industries alone. In addition, it is important to keep in mind that sector specific business/trade associations usually tend to address the “micro” issues affecting their sectors, while an umbrella services organization will focus more on the “macro” interests of its membership, including trade in services negotiations, identifying domestic and international obstacles inhibiting growth in the Egyptian services sectors, advocating for regulatory reform in services sectors, and raising awareness about the services sector generally and its competitiveness both domestically and abroad. TACKLING ISSUES RELATED TO SENSITIVE SECTORS Every country has to deal with addressing sensitive trade-related issues, especially as trading partners put pressure on the Government to liberalize and/or reform sensitive sectors and open them up to competition. Service industries are no different. This may lead to different positions among coalition members, as some members seeking open markets feel that protectionism in other sectors impedes their objectives. A coalition may not be capable of breaching such fundamental differences, but it can work in concert to help manage such issues that minimizes damage to other services sectors. In any event, it is critical that there is full information and understanding among the membership about problems facing a particular sector. Communication among the membership is critical in these situations. A services coalition can also serve to create a dialogue with other service sector entities, e.g., the Syndicates, which may not wish to support the objectives of a services coalition. For example, the coalition could establish a dialogue with the Lawyers’ Syndicate to discuss their respective views on the sector in Egypt and perhaps engage in a broader undertaking of informing the Syndicate’s constituency about the WTO and the GATS to explain the intricacies of the Agreement, how legal services fits within the scope of the Agreement, and how making commitments (or not) could potentially affect the Egyptian legal services sector. This kind of dialogue does not obligate anyone to do anything, but it does build awareness on the issues facing the Government and the sector as well as provide an opportunity for constructive discussions among all stakeholders. ASSURING BROAD PARTICIPATION IN GOVERNMENT CONSULTATIONS While Egypt does have a sub-committee on trade in services as part of the High National Committee, it represents a limited number of service providers and most likely only the largest firms. A services coalition helps assure that a more expansive range of companies that make up the Egyptian services economy contribute to its Government’s trade negotiating position. No formal Government consultative mechanism can assure this level of CHALLENGES IN THE CREATION OF A COALITION participation. A well organized coalition, that has combined its energies and creativity in putting forward complete and relevant information to the Government, can best assure a stronger Government position on services at the negotiating table. 11 Services Coalitions Worldwide Services coalitions around the world provide different examples of various ways to organize a services coalition. As we will see below, some services coalitions have started out on a more informal basis to allow time to develop relationships with potential members and to build awareness on the value of such an entity within the services community while others established a formal structure from the beginning. Exhibit 1 Coalitions of Services Industries Worldwide National Services Coalitions US Coalition of Service Industries HK Coalition of Service Industries European Services Forum Australian Services Roundtable International Financial Services, London Japanese Services Network (Keidanren) Irish Coalition of Service Industries South Asian Service Industries Forum (India) NASSCOM (India, software industry) Argentina Coalition of Service Industries Chilean Coalition of Service Exporters Canadian Coalition of Service Industries Ugandan Services Exporters’ Association Guyana Coalition of Service Providers Antigua and Barbuda Coalition of Service Industries Trinidad & Tobago Coalition of Services Industries Barbados Coalition of Service Industries St. Lucia Coalition of Service Industries Coalition of Service Industries Malaysia Multilateral and Regional Services Coalitions Global Services Network REDSERV (Americas) Global Services Coalition Financial Leaders Group (FLG) Caribbean Coalition of Service Industries Network NEW ASSOCIATION OR ENTITY Establishing a brand new association will involve the greatest degree of effort from the private sector because the coalition will be built from the bottom up. This process is probably the most time consuming, particularly for developing countries, and services firms and associations tend to struggle with the start-up activities. But it also affords the organization the ability to start from a clean palette and mold the institution to meet the interests and needs of stakeholders. 14 BUILDING AN EGYPTIAN SERVICES COALITION The U.S. Coalition of Service Industries (CSI) was formed in 1982 solely by the initiative of private sector services firms that believed services had a stake in trade negotiations and belonged on the multilateral trade agenda. CSI started out as a relatively small organization with minimal staff representing a small group of services providers. CSI has fluctuated in size through the years (in membership and staff), but has grown significantly since the early 80’s to include a diverse membership of services sectors at both the firm and the association level. Today, CSI has seven staff that manage activities; a Board of Directors that includes senior officers (e.g., President or CFO) from member companies; and, primarily operates through working groups that have either a sectoral focus (e.g., financial services, logistics, and legal services) or a functional focus (e.g., China, tax, and services trade and investment negotiations). CSI members pay annual dues, which vary depending on the level of participation or affiliation. PARTNERSHIP WITH AN EXISTING ENTITY In some cases, the most efficient way to launch a services coalition is to establish a committee or task force within an existing chamber of commerce or other business association. By doing so, champions of services issues can take advantage of the pre-existing economies of scale within in the chamber/association as well as utilize resources and staff to 1) help build awareness and capacity on services issues among all stakeholders (including non-members), and 2) take time to develop the eventual structure, membership and work program without feeling immediate pressures related to sustainability and financing. Hong Kong has evolved into a services-oriented economy, i.e., 96.4 percent of GDP (2004) and 94.4 percent of the workforce (2005).3 The Hong Kong Coalition of Service Industries (HKCSI) was formed in 1990 by the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce and currently represents more than 50 service sectors as the Chamber’s services policy think tank. HKCSI is organized into committees: the executive committee and four advisory committees that address issues specific to that sector (i.e., Financial Services Committee, Travel/Tourism Committee, Real Estate Committee, and Information Services Committee). The committees hold regular meetings to discuss issues and make recommendations. Each committee has its own terms of reference and is chaired by a HKCSI member who has expertise in that particular field. HKCSI’s activities are designed to undertake a wide range of activities and events to promote the services sector locally and internationally; to conduct research projects and studies on the development of the Hong Kong economy and services sectors; and to publish a quarterly newsletter “Hong Kong: The Servicing Economy,” an annual publication Hong Kong’s Yearly Services Statistics, as well as other publications on specific topics. HKCSI is also an active player in the global services arena, frequently participating in activities with other CSI-like organizations in Europe, the Americas and the Asia-Pacific. In Chile, the Coalición de Exportadores de Servicios (CES) was created in 1996,4 and started in line with the beginning of the negotiations on services between Chile and Canada. The Santiago Chamber of Commerce (CCS) was invited along with other associations (mainly from the professional services, banking, software and telecommunications sectors) to the negotiations. Today, CES operates as a factual association, i.e., its members do not pay an annual fee to participate in CES activities. While supported by the Chilean Government, it 3 These percentages include construction and utilities services. 4 CES’s original name was "Comité de Exportadores de Servicios" (Service Exporters Committee). SERVICES COALITIONS WORLDWIDE 15 does not participate in the financing of these activities. There are, though, some activities that are co-funded between the CCS and the public sector entity in charge of the exports promotion (ProChile). The CCS Research Department is in charge of the CES permanent secretary office, which manages the daily activities of the Coalition. The Coalition of Service Industries Malaysia (CSIM) was launched in June 2007 as an unincorporated independent forum of interested services associations. It was recognized that the Malaysian services sector has remained relatively closed when compared to the manufacturing sector, and, furthermore identified the necessity of liberalizing the sector if future growth is to be realized. The 2006 Malaysian Third Industrial Master Plan (IMP3) has targeted the Malaysian services sector setting growth rate objectives of 7.5 percent per annum (2006-2010) and contribute 59.7 percent to GDP by 2020. To accomplish these goals, the IMP3 identifies the need to establish services related forums, specifically the Malaysian Logistics Council (MLC) and the Malaysian Services Development Council (MSDC), both comprising private and public sector representatives, as well as a need for a private sector umbrella organization for the services sectors. The Malaysian International Chamber of Commerce and Industry (MICCI) has taken the lead to initiate, launch and support a platform for the services sector, forming CSIM. CSIM membership consists only of sector-centric associations. The reasoning behind this approach is to focus on the value that CSIM can provide to participants by acting as a supporting organization that supplements/focuses on a very specific mandate that reaches across all services sectors. In other words, MICCI is sensitive to the fact that it did not want others to view CSIM as an extension of MICCI or that CSIM would take away the individual authority of the existing associations. CSIM meets on a monthly basis and there are no annual fees at this point. COMBINED GOVERNMENT AND PRIVATE SECTOR INITIATIVE There are examples where association building is a joint public-private sector initiative. Funding from the Government may vary depending on the country, but this type of collaboration also demonstrates the Government’s confidence in the utility of a services coalition. Trinidad and Tobago is a semi-rich oil state with energy and gas reserves. Traditionally, the economy has focused on the energy and manufacturing sectors, but is now looking to diversify the economy as energy may become more of an uncertain (i.e., scarce) resource in the future. In August 2006, the Trinidad and Tobago Coalition of Service Industries (TTCSI) was formally launched by the Prime Minister of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago. Both the private and public sectors were involved in the actual development of TTCSI. A task force was formed to develop a constitution, perform the necessary outreach to stakeholders as well as develop a business plan and a strategy to become sustainable over the next four years. TTCSI is a private limited liability company that will receive funding from the Government for the first three years, which also plays a coordinating role. Currently members pay a one time ‘token’ amount which is based off of each associations net surplus (allowing the smaller associations to participate), and in the following years, members will pay an annual subscription based on the same methodology (net surplus). TTCSI was established as a coalition of services associations (instead of individual firms) to ensure that TTCSI does not compete with other associations. If firms have a trade or export-related issues that they would like addressed within TTCSI, it must be initiated through their association and then the association will introduce the topic to TTCSI. All services sectors can and should participate in TTCSI. 16 BUILDING AN EGYPTIAN SERVICES COALITION The development of the Barbados Coalition of Service Industries (BCSI) followed a slightly different path than many of the other examples of developing country services coalitions. In 2001, the CARICOM Secretariat encouraged member states to organize national private sector services coalitions. In 2002, the BCSI was established as a private sector initiative, and although BCSI is a private entity, it is fully funded by the Government of Barbados. Today, the CARICOM Secretariat has mandated that each Member State establish its own national coalition, each of which will then become part of a regional Caribbean Coalition of Service Industries. The objectives of BCSI focus on promoting the development and competitiveness of the Barbados’ service sectors; educating stakeholders on relevant aspects of trade agreements, negotiations, policies, and issues that affect trade in services; lobbying the Government on legislative and policy issues that support fair rules on trade in services; promoting export activities of Barbadian service suppliers; and ensuring that Barbadian service providers are able to meet the highest industry standards. BCSI helps organize the services sectors into industry associations which then become members of the BCSI—in effect, an association of service industry associations. In the future, it may be possible for individual firms to become BCSI Members independent of membership to another association. An important element of support, BCSI provides templates for the development of association bylaws and assists with the incorporation/registration of each service association. While BCSI does represent 36 services associations with services providers in both the public and private sector, these corporate members do not include tourism or offshore financial services (although these sectors can be affiliated with BCSI through an associate membership). Government Advisory Committee If establishing a new association or partnering with an existing association or federation proves to be too much of a challenge initially, another option would be to broach the subject from a different angle. The private sector could approach MTI with a recommendation to create a formal private sector advisory committee that would focus on providing input to the Government on trade-related services issues, similar to the U.S. Industry Trade Advisory Committee on Services and Financial Industries (ITAC 10). While this could be a starting point for the mobilization of the services sector as an advisory group, there may be limitations to the types of activities it is able to implement if there is no umbrella association backing it up. DONOR INITIATED In 1997, the Uganda Services Exporter’s Association (USEA) was formed as a private, nonprofit industry coalition for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and their associations through a resolution at an ITC/UNCTAD/WTO sponsored workshop. The workshop was organized by the Uganda Export Promotion Board. USEA is an advocacy and export support platform that started with 12 corporate members and seven SMEs. It represents Uganda’s services industry in multilateral, regional, and bilateral trade negotiations and has been accredited as Uganda’s National Enquiry Point on international trade in services. Establishing a Services Coalition in Egypt A services coalition is typically comprised of multiple service sectors that have identified common priorities and causes and thus have joined forces to be heard through a much stronger and more influential voice that represents a diverse cross-section of service sectors. An important basis for establishing a services coalition is that it should distinguish itself from existing business and trade associations, which tend to focus on sector-centric issues. A services coalition does not have to represent all services sectors, since there may be services sectors that will not support the broader objectives of the coalition. However, it does need to represent a critical mass of private sector firms to ensure support for creating such an entity. Defining critical mass is going to vary from country to country, and in some cases, according to the legal form of the entity. For example, in Egypt, if the services coalition decides to organize itself in the form of an association, there must be a minimum of 10 persons (either natural or juridical) that make up the initial membership. Several approaches to establishing a services coalition are possible. The key elements to take into account are the following: Build critical mass. The first step to establishing a services coalition is determining whether or not there is sufficient interest from a cross-section of private sector services providers. TRAC has taken the initiative to reach out to the AmCham’s membership (and beyond) in the form of informal and formal (i.e., roundtable discussions) consultations with services providers to 1) gauge their interest in creating a services coalition, 2) discuss stakeholder concerns, and 3) build knowledge and understanding among stakeholders on the objectives and activities of a services coalition. Reaction from Egyptian service providers, including the financial, telecommunications, management, and tourism sectors, has been very positive. Ensure Government buy-in. In Egypt, Government buy-in to creating a services coalition is important as it sends a message to all stakeholders that it sees the value in having such an entity and is willing to collaborate with the coalition on trade in services issues. Identify leader(s). Leadership of the coalition is key, especially during the critical start-up phase. A dynamic Chairperson will need to be the “champion” of the coalition, lending time and energy to promote the services coalition, provide direction to the membership, chair meetings when appropriate, and raise the profile of the coalition. In addition, the Chairperson will have to have a good working relationship with Government officials. Once the coalition is up and running, it is equally important to identify a qualified individual to act as the executive director of the coalition. This person will be knowledgeable about trade in services and will manage the day-to-day activities of the coalition, providing leadership in developing and carrying out coalition objectives. 18 BUILDING AN EGYPTIAN SERVICES COALITION Determine where and how to organize. Because of preliminary financial burdens and a lack of full-time staff resources that tends to be associated with developing a formal association in Egypt, it was suggested that a Core Services Committee be established within the AmCham with the understanding that this should not prejudice any future proposal to formalize a services coalition outside of the AmCham at a later date. There are a number of benefits to this approach. First, services coalitions in developing countries can take several months to a couple of years to establish, primarily because there may be a need for a certain amount of capacity building among all stakeholders (i.e., private sector, government, regulatory bodies, etc.) on the objectives and benefits of a services coalition. The Core Services Committee can be instrumental in drafting its mission statement, short- and long-term visions, and functions. Once the coalition appears to be sustainable, stakeholders should then discuss different options to establishing an initial structure either keeping it within the AmCham or moving it outside in the form of an Association, a Council (e.g., the Competitiveness Council), or a Federation. The potential risk in this approach is that it could potentially be regarded as an “American” initiative. However, if there is strong leadership coming from a number of large Egyptian firms, this could mitigate the above mentioned risk. Alternatively, a task force comprised of an initial group of dedicated service providers (with support from TRAC or TAPR II) could be formed and charged with a mission to carefully review the organizational structures of other CSI’s to determine which might be most appropriate for Egypt. It may be worth inviting an official from one of these services coalitions to discusses their experiences in more detail and with a broad group of Egyptian services stakeholders. Develop an initial work plan of activities. Such activities could include: Organizing meetings with services negotiators to discuss EU, GAFTA and other negotiations; Identifying priorities and drafting position papers on key trade in services issues; Inventorying and publishing domestic regulatory measures that affect the provision of services (i.e., cross-border) and services providers in Egypt; Launching surveys in key services sectors to provide a better understanding of the impact that these particular sectors contribute to the Egyptian economy; Examining export markets for Egyptian services and service providers and identifying obstacles to export growth (both domestically and in the host market); Creating a strategy to address issues related to the recognition of professional degrees with key trading partners; Organizing an international conference with heads of other CSI’s to build awareness of the impact that these institutions have had in their home market as well as in the international arena; and Working with Central Bank and CAMPAS to improve the reporting of services data to improve services statistics at the national level. ESTABLISHING A SERVICES COALITION IN EGYPT 19 The above list is illustrative and should be thought of as flexible to adjustments suggested by committee members. It should be noted that many of these activities could be undertaken in collaboration with other interested groups such as think tanks, academia, research institutes, and donor projects (e.g., TAPR II). The Committee should explore options to minimize costs and maximize collaborative efforts. NEXT STEPS Egypt already has a critical mass of interested firms representing several services sectors. There are a couple of organizational and substantive steps that could be undertaken over the next few months. First, the proposal should be presented to Minister Rachid to garner his support and buy-in to the process. He (or his staff) may also have some concrete suggestions on potential activities that could support ongoing trade negotiations or regulatory reform efforts. Second, a meeting with the Ministry’s services negotiators should be organized to present current standings in services negotiations with the EU, GAFTA, and COMESA. MTI could provide an overview of the negotiations and highlight contentious issues, while at the same time solicit input from the private sector. This meeting will also provide the private sector with a preview of the type of work/input that is needed from a services coalition. Third, an organizational meeting of services stakeholders should be scheduled to review the organizational options, and to push the identification of a Chair and a Vice-Chair. At this point, it may be a good idea to form a task force consisting of interested services firms to take charge of reviewing possible options for organizing either formally or informally. Follow on activities should also be discussed and a proposed work plan of potential issues should be identified. It will probably fall upon TRAC and/or AmCham to help facilitate the work of the services coalition, at least until a long-term plan and a structure are in place. References International Trade Centre (ITC), Creating a Services Coalition: an East African Roadmap. ITC, Trade in Services, Coalition of Service Industries Why and How. SELECTED WEBSITES Australian Services Roundtable: www.servicesaustralia.org.au Barbados Coalition of Service Industries: www.bcsi.org.bb Coalición de Exportadores de Servicios (Services Exporters Coalition – CES): www.chilexportaservicios.cl U.S. Coalition of Service Industries: www.uscsi.org European Services Forum: www.esf..be Hong Kong Coalition of Service Industries: www.hkcsi.org.hk Uganda Services Exporters Association: www.ugandaexportsonline.com/service_exports.htm The Trade-Related Assistance Center- TRAC/AmCham 33 Soliman Abaza Street, 9th Floor Dokki, Cairo Phone: +2 02 338-1050 Fax: +2 02 749-1528 www.egypttrade.org Technical Assistance for Policy Reform II BearingPoint, Inc. 8 El Sad El Aali Street, 18th Floor Dokki, Giza Egypt Country Code: 12311 Phone: +2 02 335 5507 Fax: +2 02 337 7684 www.usaideconomic.org.eg