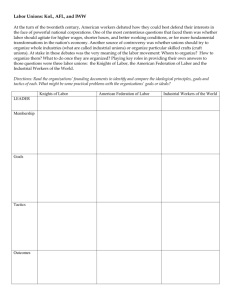

KNIGHTS OF LABOR

advertisement

Name: _________________________ Date: ________________ KNIGHTS OF LABOR The Knights of Labor began as a secret society of tailors in Philadelphia in 1869. The organization grew slowly during the hard years of the 1870s, but worker militancy rose toward the end of the decade, especially after the great railroad strike of 1877, and the Knights' membership rose with it. Grand Master Workman Terence V. Powderly took office in 1879, and under his leadership the Knights flourished; by 1886 the group had 700,000 members. Powderly dispensed with the earlier rules of secrecy and committed the organization to seeking the eight-hour day, abolition of child labor, equal pay for equal work, and political reforms including the graduated income tax. Unlike most trade unions of the day, the Knights' unions were vertically organized—each included all workers in a given industry, regardless of trade. The Knights were also unusual in accepting workers of all skill levels and both sexes; blacks were included after 1883 (though in segregated locals). On the other hand, the Knights strongly supported the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the Contract Labor Law of 1885; like many labor leaders at the time, Powderly believed these laws were needed to protect the American work force against competition from underpaid laborers imported by unscrupulous employers. Powderly believed in boycotts and arbitration, but he opposed strikes. He had only marginal control over the union membership, however, and a successful strike by the Knights against Jay Gould's southwestern railroad system in 1884 brought a flood of new members. By the beginning of 1886, there were 700,000 Knights of Labor. But when the workers struck the Gould system again in the spring of 1886, they were badly beaten. Meanwhile, other members of the Knights participated—again, over Powderly's objections—in the general strike that began in Chicago on May 1, 1886. When a bomb explosion at a workers' rally in Haymarket Square May 4 triggered a national wave of arrests and repression, labor activism of every kind suffered a setback, and the Knights were particularly—though unfairly—singled out for blame. By 1890, the membership had fallen to 100,000. Although Powderly's somewhat erratic leadership and the continuing factionalism within the union undoubtedly contributed to the Knights' demise, the widespread repression of labor unions in the late 1880s was also an important factor. HAYMARKET AFFAIR The Haymarket affair began when a bomb exploded among a squad of policemen at a workers' rally in Haymarket Square, Chicago, on May 4, 1886. Since May 1, a loosely organized national strike for the eight-hour day had been gaining momentum in Chicago. On May 3 strikers had come to the support of an already-existing strike at the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company; police had fired on the crowd and four people had been killed. The Haymarket rally, organized by a small anarchist group, was one of many called to protest the killings. Only thirteen hundred people attended, and most left when it began to rain. About three hundred remained when 180 police arrived and demanded that they disperse. Suddenly a bomb exploded among the policemen, killing one and wounding many more, including seven who died later. The police responded with wild gunfire, killing seven or eight people in the crowd and injuring about a hundred, half of them fellow officers. The Haymarket bombing triggered a national wave of fear; public officials, civic leaders, the press, and some union leaders joined in equating foreign birth with anarchism and terror. In Chicago hundreds of socialists, anarchists, and Period: ______ other radicals were rounded up. Eight anarchists (all but one of them German immigrants) were indicted for conspiracy, though none was charged with throwing the bomb. After a conspicuously biased trial, seven were condemned to hang; the eighth was given a long prison sentence. The convictions were upheld in September 1887, and the executions set for November 11. On November 10 one of the condemned men, Louis Lingg, hanged himself; a few hours later, Governor Richard J. Oglesby commuted two of the men's sentences to life imprisonment. The remaining four, Albert Parsons, August Spies, Adolph Fischer, and George Engel, were executed on schedule. On June 26, 1893, Governor John Peter Altgeld pardoned the three survivors, Samuel Fielden, Michael Schwab, and Oscar Neebe. This action, though applauded by many, was also widely criticized and probably contributed to Altgeld's defeat for reelection. The nativistic fear of immigrants and radicals aroused by Haymarket lingered for years, preparing the ground for further red scares in the future. AMERICAN FEDERATION OF LABOR The American Federation of Labor (AFL) was organized as an association of trade unions in 1886, growing out of an earlier Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions founded in 1881. The AFL's president, Samuel Gompers (who served nearly every year until 1924), was convinced that unions open to workers of all types of skills within a given industry—called industrial unions—were too diffuse and undisciplined to withstand the repressive tactics that both government and management had used to break American unions in the past. The answer, he believed, was craft unions, each limited to the skilled workers in a single trade. According to Gompers's "pure and simple unionism," labor should not waste its energies fighting capitalism; its sole task was to hammer out the best arrangement it could under the existing system, using strikes, boycotts, and negotiations to win better work conditions, higher wages, and union recognition. Applying this philosophy to politics, the AFL refused to ally itself with the Socialist party or with independent labor parties. Instead, Gompers argued that labor should "reward its friends and punish its enemies" in both major parties. After 1908, the organization's tie to the Democratic party grew increasingly strong, but the AFL continued to concentrate on political protection for unions, rather than seeking social change through legislative action. By 1904, the AFL claimed 1.7 million members. Although the union represented only the more privileged members of the country's work force, it gained increasing influence as the recognized voice of American labor. Its membership declined between 1904 and 1914 in the face of a concerted open-shop drive by management but rose again during World War I, when unions were given considerable government protection. By 1920 the AFL had nearly 4 million members. After the war, however, business resumed its union-busting activities, and the AFL lost ground throughout the 1920s. By the time the New Deal opened the door again to organized labor, the AFL—now led by William Green (president, 1924-1952)—was facing increasing dissension within its ranks. Craft unions had proved ineffective as a way of organizing the huge industries, such as auto, rubber, and steel, that now dominated the economy. Many in the AFL believed that only industrial unions fit the modern Name: _________________________ Date: ________________ pattern of production. In 1935 John L. Lewis led the dissenting unions in forming a new Committee for Industrial Organization within the AFL. This group, which became the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), grew so powerful that the AFL expelled the ten CIO unions in 1937. The AFL and CIO continued as separate organizations during World War II but were reunited in 1955. The AFL—CIO was now the nation's dominant labor organization, but this achievement was already being undermined by changes in the American economy and work force—most notably, the growing loss of jobs in the manufacturing sector where unions had been strongest. In 1945 nearly one-third of American workers belonged to a union; by 1990 the proportion had fallen to less than onefifth. GOMPERS, SAMUEL(1850-1924), cofounder and first president, American Federation of Labor. Born into a Jewish working-class family in London, Gompers migrated with his family to New York City in 1863. Taught both the cigar trade and union principles by his father, Gompers thrived in the heady atmosphere that surrounded New York's labor movement during the 1870s. Advocates of Marxist and utopian socialism, anarchism, communalism, and a host of other reform programs jostled for support. Influenced by British trade union principles and by the Marxist emphasis on the primacy of economic organization of workers, Gompers favored the creation of strong, centralized trade union institutions that would foster the growth and direct the activity of local unions. In conjunction with Adolph Strasser and others, Gompers restructured the Cigar Makers International Union along such lines. Although never an avowed Marxist himself, Gompers's approach to organizing workers owed much to two ideas advanced by Marxists. He agreed with them that it was only through the trade union that awareness of a broad class interest among workers could emerge. And it followed from this that Gompers and such early American Marxist labor leaders as Friedrick Sorge and J. P. McDonnell looked upon political activity with suspicion. The state had proved hostile to workers in both Europe and America; any gains won through political reform, they argued, could be enforced only by the concentrated power of organized workers in the factories and shops across the nation. In an era when craft workers still controlled important aspects of production, Gompers and his associates insisted upon craft organization as the foundation for the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions (1881) and its successor organization, the American Federation of Labor (AFL; 1886). The AFL grew over its first two decades until in 1904 it accounted for some 10 percent of all nonagricultural wageworkers. But the emphasis on skilled craft workers created a de facto exclusion of the less skilled at a time when these workers were becoming an increasingly Period: ______ important sector of the work force. This resulted in an organization of workers deeply divided along racial, gender, and ethnic lines. The weak position of the president of the AFL (its constitution ensured the autonomy of the constituent unions) largely precluded Gompers from broadening organizing efforts. As government regulation of industrial relations grew, the AFL felt compelled to seek political alliances and in 1912 actively supported the successful Democratic candidate for president, Woodrow Wilson. During Wilson's two terms, Gompers helped shepherd through Congress the Clayton Anti-Trust Act and the Seamen's Act. With the advent of World War I, the Wilson administration pressured business to negotiate with union leaders in order to guarantee production, and the union's membership grew impressively. During the postwar years, however, neither governmental nor business connections (developed largely through Gompers's leadership position in the National Civic Federation) defended labor during the steel strike of 1919, the machinists' strike of 1922, or the nationwide anti-union campaign known as the "American Plan." At Gompers's death the AFL's weakened membership and narrow organizational structure underscored both the fragility of labor's position in American society and the necessity of expanding organizing efforts. In the following decade the AFL and recently formed industrial unions would address those problems anew. CONGRESS OF INDUSTRIAL ORGANIZATIONS The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) was founded in response to the failure of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) to organize unskilled workers in mass production industries. At the 1934 AFL convention, a move to organize these workers lost when only 30 percent of the members voted for the measure. After failing again in 1935, John L. Lewis, head of the United Mine Workers, Sidney Hillman, leader of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers, David Dubinsky of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, and representatives of the Textile Workers and the Typographers unions formed the Committee for Industrial Organization. It was expelled from the AFL in 1936 and became the CIO in 1938. The National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, section 7A, which gave workers the right to organize and bargain collectively, provided an impetus to unionization in the 1930s. The CIO's major organizing tactic was the sit-down strike, which was quite successful: CIO membership reached 2,654,000 by 1940. John L. Lewis was the first president of the CIO. Responding to the passage of the Taft-Hartley Act in 1947 and the election of a Republican president in 1952, the AFL and the CIO merged in 1955.