Welcome To Moldova - Marisha and friends in Moldova

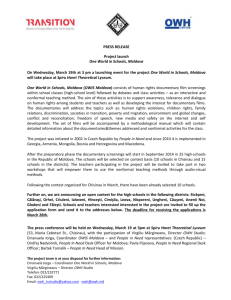

advertisement