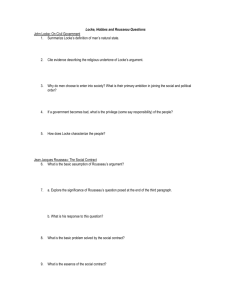

Natural Rights Ethics

advertisement

Ethics based on Natural Rights General Comments We are dealing with the question “How can we justify our ethical principles? Our standards of morality? Our values? We have seen that we cannot simply rely on our feelings, or the law, or religion, or what society accepts as ethical, or on science. The main approach taken by philosophers has been to provide arguments based on a notion of “truth”. If we can discover timeless truths, then we should be able to derive ethical principles from that truth. During the middle ages the church dominated intellectual and social life. Morality was justified by claiming that rules came from the truth of a higher authority – God. As the Greeks came to be rediscovered, Plato and Aristotle were also considered the authorities in many matters of importance, such as the nature of the world and how we obtain knowledge of it. In the 16th and 17th centuries several developments made it clear that the institution of the church and its view of nature was no longer adequate for guiding people in how to live. Science became increasingly important as a way of knowing. Social changes were brought about by the discoveries of other lands and subsequent increase in trade. The population gradually became more urban and the feudal system was disappearing. With social change new problems of living arise and new forms of human relationships. This leads to a questioning of traditional moral values and the basis for their authority. It was a time of growing liberalism and individualism. Traditional authorities such as the Church and Greeks were being questioned. The morals of the Church, its view of human nature and our place in the world, were too inflexible and did not meet the new demands that came with changing human relationships. All three of the philosophers we consider here – Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau – were impressed with science as a way of discovering truth and tried to use the methods of science to discover universal moral principles. We must emphasize that they shared with the Church that the goal was to discover universal moral principles, but the methods by which we come to know them were to differ. Truth was still to be found, but the basis for moral authority changes from coming from a higher authority like God to a basis in the methods of science. Now it was science that could lead us to the truth. Hobbes and Locke especially were very impressed with science. Looking at the advances in astronomy that were based on geometry and deduction, they believed that certain undisputable truths could be discovered about ethics based on principles deduced from postulates about human nature. In other words, if we could define human nature, then universal ethical principles would follow. Rousseau agreed with this basic approach of using logic and deducing principles. However, he was more impressed with science as having a negative effect on morals. All of them - Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau - believed that the best way to discover human nature was to try to characterize what humans would be like independently of social life. Therefore they attempted to characterize man in a “state of nature” – that is, without social influence. They differed in their conclusions about what such a state would have been like. Hobbes believed that although we had no possible historical evidence that he could deduce what human life must have been like prior to society. He characterized life as being warlike, everyone out for himself, amoral. Restraint in our behavior towards others was pragmatic – agreements between individuals was smart simply to avoid being killed by the other. However, no real trust was possible. For this reason, for our own long-term survival, we form a social contract, give up our individual rights to take anything we want, and put ourselves in the hands of a sovereign (ruler) whose overall function is to protect the good of the whole. Locke felt that we could, at least imagine, what life was like prior to society. He also believed it was a war-like situation, but that we were aware of divine law, God’s morality, even in a state of nature. This was available to us if we used our reason, which was given to us by God. Rousseau also believed that we existed in a pure state of nature, but that it was ideal. He said that we had been corrupted by modern science and art. Deception and false manners, mediocre art, were characteristic of “civilized” societies. Thomas Hobbes (1588 - 1679) Hobbes lived at the same time as Galileo, and he was deeply impressed with the precision and certainty of science. He was impressed by Copernicus, not only for his questioning of the traditional view of the sun and the earth, but for the method he employed - the observation of moving bodies and the mathematical calculation of the motion of bodies in space. Galileo had further sought to give astronomy the precision of geometry. These people believed that the world was logical, and that if we use deductive logic – starting with axioms or postulates and then deriving logical consequences, that we are actually making discoveries about the world. Therefore, if anyone uses the appropriate method, it is possible to have real knowledge of things as they are. In this way we can have direct access to the truth, and we do not have to go back to ancient authorities like Plato or Aristotle for an understanding of the world.. Hobbes therefore believed that ethical principles could be derived empirically just like we derive an understanding of the motions of planets and stars. This was to be done by the use of logic. Morality and Political Life Hobbes believed that we could consider humans to be just like objects moving in space, and by using deductive logic we could describe human nature and the nature of the state. To discover human nature and the nature of society Hobbes believed that we had to first consider what human nature was like independent of society. One possible way of doing this would be to conduct an historical analysis using information about how humans lived prior to society. However, he admitted that we did not have any information about what life was like prior to society. This really didn’t matter though, because we could deduce what human nature in its “pure” form was like by using logic and analysis. From axiomlike premises he deduces all the consequences or conclusions of his political theory, and most of these premises cluster around his conception of human nature. So what is “human nature”? The State of Nature – men as they appear before there is any state or society. All men are equal in that they have the “right” to whatever they consider necessary for their survival. “Equality” here does not mean something moral, but means that anyone is capable of hurting his neighbor and taking what he judges he needs for his own protection. There are no “rights”, there is simply the freedom “to do what he would, and against whom he thought fit, and to possess, use and enjoy all that he would, or could get. The will to survive is the driving force for man, and the pervading psychological mood is fear – fear of death and particularly violent death. Hobbes presents a picture of men moving against each other like physical bodies in motion – they are motivated by appetite and aversion (or love and hate, or good and evil). We are attracted to that which we like and which will help us survive, and hate whatever we think is a threat. We are fundamentally egotistical in that we are concerned chiefly about our own survival and identify goodness with our own appetites. So why would we create an ordered and peaceful society? Natural Laws Even in this anarchic situation there are “natural laws” which men know because they follow logically from our principle concern with our own safety. A natural law is a general rule, discovered by reason, telling what to do and what not to do. 1. The first law is “every man ought to seek peace and follow it.” In other words, I conclude that I have a better chance of survival if I make peace. 2. The second law says that a man is disposed to give up some freedoms if others do too. This leads to the creation of the Leviathan, or “artificial man” (the commonwealth or state). The Social Contract A “contract” between individuals, established by mutual agreement, to give up their right to govern themselves and authorize a person or group of persons to govern. This governing body or “sovereign” expresses the collective will of the people. In agreeing to live in society, each individual gives up their power of individual will for the collective will. A sovereign, since he represents the collective will, has complete right and power to govern and is not subject to the will of the individual citizens. This of course is a totalitarian scheme and would certainly seem hard to justify for ourselves, being used to more democratic kinds of freedoms. Hobbes though is trying to deal with the age-old problem of how to deal with the conflictive interests of the citizens in a society, and how to avoid civil war. If we all make a contract, a binding agreement, and abide by it, then we can have social order and progress for the whole of society, In this way we give up the anarchy that characterizes the state of nature, men living outside of community. The only way out of anarchy is to create a single will. Technically this is not tied to any particular form of government. May even be a form of democracy, though not exactly like contemporary ones. Resistance to sovereignty is not permitted because the sovereign actually embodies the will of the people. Therefore to resist would be resisting oneself, and to resist would be to revert to independent judgment, which is to revert to the state of nature of anarchy. The power of the sovereign must therefore be absolute in order to secure the conditions of order, peace, and law. Ethics and Morality We saw that in the state of nature there is nothing we would call “morality.” Humans would be living in a state of “survival of the fittest” and any kind of rules adopted would be temporary agreements to stay out of each other’s way. Morality and justice are created when we form the social contract and agree to be bound by the rules of a sovereign. Only if there is a sovereign is there law, and in fact morality. Morality is the same as the law. And there can be no unjust law, since the law is the will of the people. If morality arises only with the social contract, there is no concept of justice and morality that exists prior to, or above the sovereign, that limit the powers of the sovereign. In other words, the sovereign is not subject to any higher authority and the sovereign does by definition what is “just.” So what is “just” is defined by the decisions of the sovereign. So to be moral, one has to follow the law and abide by decisions of the sovereign. However, there can be bad laws. A bad law is one that does not protect the safety of the people, because that was the purpose of putting our confidence in the sovereign in the first place. The sovereign is the sole judge of what is good for the people. If it weren’t so, anarchy would ensue. If the sovereign does something bad, it is a matter between him and God. Comment: The "contract" theory of social organization may be worthless as fact (there is no historical support for such a claim, nor for the idea that a “state of nature” existed prior to society), but it did reflect the developing idea that the state existed to satisfy human needs and that it could be controlled by human volition and intention. As such it is a critique of Aristotle's idea that the state existed as a product of nature, independent of human intentions and beyond human choice. In the contract theory humans bring the state into existence by their decisions. A political individualism. Although this sounds far-fetched to us living in this democratic society today, very similar arguments in the recent past have been given to justify the rise to power of dictators. Most dictators take over a country on the rationale of preventing a further slide into anarchy. They take power in the name of the collective will of the people. They define justice as retribution against the opposition. They define morality by passing laws on censorship, sexual behavior, the conditions of association. John Locke (1632-1704) More than perhaps anyone else, Locke represents the individualism and liberalism of 17th century England. He believed (as did Hobbes and Rousseau) that we had to invent new philosophies in order to provide a solid basis for knowledge, rather than rely on old authorities. He was a proponent of empiricism, the idea that all knowledge comes from experience. We can only know the truth therefore by relying on actual experience. Moral and Political Theory Morality is a form of demonstrative knowledge, with the precision of mathematics (in other words, we use logic to reach conclusions about the nature of reality). If we can define our basic terms with precision, then we can understand their congruities and incongruities (whether they are logical or illogical). Theories of ethics all have to presuppose some notion of what is “Good.” For Locke, the “Good” is perfectly definable – things are good or evil only reference to pleasure or pain. That we call good which is apt to cause or increase pleasure, or diminish pain in us. Therefore morality has to do with choosing or willing whatever leads to pleasure and minimizes pain. Furthermore, moral laws are based on what helps us achieve the “Good”. He says: “moral good and evil is only the conformity or disagreement of our voluntary actions to some law.” There are three types of law to which humans are subject: 1. law of opinion – a community’s judgment of what kind of behavior will lead to happiness: conforming to this law is called virtue, although this differs according to community. 2. civil law – set by the commonwealth and enforced by the courts. This tends to follow the first since in most societies the courts enforce those laws that embody the opinion of the people. 3. divine law – known by reason or revelation – the true rule for human behavior. In the long run the law of opinion and of civil law should be made to conform to divine law. Locke is convinced that he has proven that God exists, and then that we can discover moral rules that conform to god’s law through the use of demonstrative logic, and that we can determine moral rules as easily and as precisely as with mathematics. These laws are often in contradiction with each other. The reason is that men everywhere tend to choose immediate pleasure over that which has more long lasting value. In the state of nature men have access to Divine Law and so should know what is right and wrong. However, men do not always use their reason. Also, the law of opinion is small early communities may be contrary to Divine Law. Therefore some social order is necessary. Ultimately, the best law is the divine law, and the law of opinion and the civil law should ultimately conform to it. The State of Nature Locke agreed that one’s personal survival was important for humans living in a “state of nature” prior to society. However, he didn’t conceive this situation as a “war of all against all” as did Hobbes. Rather, “men living together according to reason, without a common superior on earth with authority to judge between them is properly the state of nature.” Even in the state of nature we know the moral law because humans are rational by nature, and if we use our rationality we will understand certain ethical principles. “Reason, which is that law, teaches all mankind who will but consult it, that, being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty or possessions.” So this is not simply an egotistical law of self-preservation, but the positive recognition of each man’s value as a person by virtue of his status as a creature of God. This implies rights with correlative duties, especially the right to property. The Social Contract and Private Property For Hobbes, there could only be private property after a legal order had been set up. This legal order is the “social contract.” Locke says that private property precedes the civil law, for it is grounded in natural moral law. The justification for private ownership is labor. Transforming something through our labor puts something of ourselves in it. We transform what was common property into private property though our labor. There is a limit to amount of private property we can accumulate to “as much as anyone can make use of to any advantage of life before it spoils, so much he may by his labor fix a property in”. In other words, no one has a right to endlessly accumulate property. The amount of property we have should be limited to what we can reasonably use during our lifetimes. There is a also a natural right to be able to inherit property. Civil Government Men only leave the state of nature (in which they have natural rights and know the moral law) only to protect their property. The main function of government is therefore the protection of property. By “property” is meant “lives, liberty and estates” In the state of nature we are capable of knowing moral law if we put our minds to it, but, unfortunately, we don’t. When disputes occur, every man is likely to judge in his own favor. Therefore we need a set of written laws and also an independent judge. Because of the inalienable character of rights, political society must rest upon the consent of men, for “men being…by nature all free, equal and independent, no one can be put out of this estate and subjected to the political power of another without his consent. We consent to have laws made and enforced by society, but these laws must confirm those rights we have by nature. The government should also have the consent of the majority. If we enjoy the privilege of citizenship, own and exchange property, rely upon the police and the courts, we have in effect assumed also the responsibilities of citizenship and consent to the rule of the majority. Sovereignty Locke’s concept of the sovereign is very different from Hobbes. The Sovereign does not have absolute power, but power should be in the hands of a legislature, which is, in effect, a representation of the majority of citizens. He emphasized the importance of a division of powers so that those who make the laws do not also execute them. The executive (president, King, or whatever) is also subject to the law. The people have the supreme power to remove the legislative branch if they act contrary to the wishes of the people. There is a right to rebellion, but only when government has been dissolved by an external enemy or by an alteration of the legislature. The latter happens, for example, when the executive substitutes his law for the legislature’s or if he neglects the execution of the official laws. Comment: John Locke was also a religious man. Therefore it is no surprise that the ethical principles he came up with were consistent with Christian ethics. The difference is that moral rules no longer came from God through the church, but came from God in the way He made us. He gave us the ability to reason as a way of knowing what his will is. This means that everyone of us as individuals has to “discover” what is morally right and morally wrong using our reasoning. However, our reason has been given to us by God and therefore it is in the nature of reason, if used appropriately, to come to certain conclusions about morality that God wants us to have. What has been done here is to increase individual responsibility at the expense of the Church. Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778). Geneva. Rousseau’s career developed during the French Enlightenment of the 18th century. Other notable figures, called the philosophes, were Voltaire (16941778), Montesquieu (1689-1755), Diderot (1713-1784), Condorcet (1743-1794) These were dissident thinkers who challenged the traditional modes of thought concerning religion, government, and morality. Human reason was believed to provide the most reliable guide to man’s destiny. Diderot and d’Alembert edited the Encyclopédie (1751-1780), a 35 volume compendium of all knowledge. Rousseau, with little formal education, ended up overshadowing the other thinkers of his time. Major Themes Rousseau believed that morals had been corrupted by the replacement of religion with science, by sensuality in art, by licentiousness in literature, and by the emphasis upon logic at the expense of feeling. (Discourse on the Arts and Sciences – 1750). Man is by nature good, and our modern institutions have made him bad. In the state of nature, humans were not much better but the arts and sciences have produced significant changes to make things worse. Our morals were rude, but natural. Art and literature have moulded our passions to speak an artificial language. Modern manners have made everyone conform in speech, dress, and attitude, always following the laws of fashion, never the promptings of our own nature, so that we no longer dare to appear as we really are. Mankind has become a kind of herd – we all behave exactly alike – and so we never know even among our own friends with whom we are dealing. Human relationships are now full of deceptions. In the state of nature, men could easily see through one another, an advantage which prevented them from having many vices. He also attacked excessive luxury and politicians who talk only about economics and no longer talk of virtue. We should acknowledge the role of women – if you want men to be noble and virtuous, teach women what these things are, because men are what women make of them. He was worried that the free marketplace of ideas characteristic of modern society would lead to moral scepticism. In this regard there are four points he made about science and society: 1. Science and philosophy seek universal truth, thereby undermining the validity of local opinion. 2. Science emphasizes proof and evidence, but dominant social opinions about values cannot be demonstrated conclusively, without a doubt. 3. Society is held together by faith, not knowledge. 4. Science undermines patriotism because the scientist tends to be cosmopolitan (today we would say “international”), while patriotism requires a strong attachment to one’s own society. To counteract these trends in society, a strong government is necessary and, according to Rousseau, paves the way for despotism. The problem is not so much with science and philosophy, because Rousseau also believed in Reason. It is the popularisation of these methods that is the problem. Science belongs only to the few. We distort knowledge by trying to make it popular. Virtue and morals are simple, and we need to find them in our own hearts. The Social Contract We can’t know about the transition from a state of nature to society, but we can answer why it is that a person ought to obey the laws of government. “Man is born free; and everywhere he is in chains.” State of Nature – man was happy because he lived entirely for himself and therefore possessed an absolute independence. Humans were motivated by a natural sentiment which inclines every animal to watch over his own preservation, and which, directed in man by reason and pity, produces humanity and virtue. There is no such thing as original sin - the origin of evil is to be found in the later stages of man’s development in society. With social contacts comes vices, for now he is motivated by “artificial sentiments” which are born in society and which lead every individual to make more of himself than every other, and “this inspires in men all the evils they perpetrate on each other”, including intense competition for the few places of honour, as well as envy, vanity, pride, and contempt. It was probably impossible to live alone simply because of increasing numbers of people. Problem – how to reconcile original independence with the inevitability of having to live together? The solution – a social contract which is a living reality of any present government. It is a principle that helps overcome the lawlessness of absolute license and assures liberty, because everyone willingly adjust his conduct to harmonize with the legitimate freedom of others. What we lose is our “natural liberty· – an unlimited right to everything, and gain a “civil liberty” – and a property right in what we possess. We place ourselves and all our power in common under the supreme direction of the general will and receive each member as an indivisible part of a whole. Anyone who refuses to obey the general will shall be compelled to do so by the whole body – “this means that he will be forced to be free.” The “general will” is the will of the sovereign. The sovereign is the total number of citizens of a given society, the single will which reflects the sum of the wills of all the individual citizens. We realize that in thinking of our own good that we should refrain from any behavior that would cause others to turn upon and injure us. Each citizen understands that his own good and his own freedom is connected with the common good. Ideally, therefore, each individual’s will is identical with every other individual’s since they are all directed to the same purpose, namely the common good. Laws are therefore actually our own will, and so by disobeying a law we are disobeying ourselves. “General will” vs. “will of all” – both are concerned with the common good or justice, but when the “will of all” means voters in a group then there is the possibility of special interests arising that are contrary to the general will. Society may break up into factions. Factions or competing interest groups should not be a part of the state. If people are given adequate information and had the opportunity to deliberate, even if they do not communicate with each other, they would choose the path leading to the common good. This provides the setting for the greatest possible freedom If someone disobeys a law, and assuming that it represents more than special interests but the general will. If we disobey a law we are in error. We make mistakes, and if we use our reason we will have to come to see that we are mistaken. If we accurately understand the requirements of the common good (which provides us with the greatest amount of freedom) we would obey, or be forced to be free.” Comments The theory formed with small-town Geneva in mind. It would be more impractical in a large nation. The theory constitutes an attack on the Age of Reason. Gave impetus to the Romantic movement by emphasizing feeling Revived religion even though he had doubts about some traditional teachings Provided a new direction for education Inspired the French revolution Influenced Immanuel Kant.