Chap021

advertisement

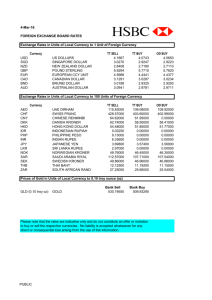

Chapter 21 - International Corporate Finance Chapter 21 INTERNATIONAL CORPORATE FINANCE SLIDES 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 21.7 21.8 21.9 21.10 21.11 21.12 21.13 21.14 21.15 21.16 21.17 21.18 21.19 21.20 21.21 21.22 21.23 21.24 21.25 21.26 21.27 21.28 21.29 21.30 Key Concepts and Skills Chapter Outline Domestic Financial Management and International Financial Management International Finance Terminology Global Capital Markets Exchange Rates Example: Exchange Rates Work the Web Example Example: Triangle Arbitrage Types of Transactions Absolute Purchasing Power Parity Relative Purchasing Power Parity Example: PPP Covered Interest Arbitrage Example: Covered Interest Arbitrage Interest Rate Parity Unbiased Forward Rates Uncovered Interest Parity International Fisher Effect Overseas Production: Alternative Approaches Home Currency Approach Foreign Currency Approach Repatriated Cash Flows Short-Run Exposure Long-Run Exposure Translation Exposure Managing Exchange Rate Risk Political Risk Quick Quiz Ethics Issues CHAPTER WEB SITES Section Introduction 21.1 21.2 Web Address www.adr.com www.bloomberg.com www.swift.com www.xe.com www.exchangerate.com www.ft.com 21-1 A-2 CHAPTER 21 CHAPTER WEB SITES - CONTINUED 21.4 21.7 www.travlang.com/money cbs.marketwatch.com www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook CHAPTER ORGANIZATION 21.1 Terminology 21.2 Foreign Exchange Markets and Exchange Rates Exchange Rates 21.3 Purchasing Power Parity Absolute Purchasing Power Parity Relative Purchasing Power Parity 21.4 Interest Rate Parity, Unbiased Forward Rates, and the International Fisher Effect Covered Interest Arbitrage Interest Rate Parity Forward Rates and Future Spot Rates Putting It All Together 21.5 International Capital Budgeting Method 1: The Home Currency Approach Method 2: The Foreign Currency Approach Unremitted Cash Flows 21.6 Exchange Rate Risk Short-Run Exposure Long-Run Exposure Translation Exposure Managing Exchange Rate Risk 21.7 Political Risk 21.8 Summary and Conclusions ANNOTATED CHAPTER OUTLINE Slide 21.1 Slide 21.2 Slide 21.3 Key Concepts and Skills Chapter Outline Domestic Financial Management and International Financial Management CHAPTER 21 A-3 21.1. Terminology Slide 21.4 International Finance Terminology American Depository Receipt (ADR) – security issued in the U.S. that represents shares in a foreign company Cross-rate – exchange rate between two currencies implied by the exchange rates of each currency with a third Eurobond – bonds issued in many countries but denominated in a single currency Eurocurrency – money deposited in the bank of a foreign country (dollars deposited in a French bank are called Eurodollars) Lecture Tip: Eurodollars are “deposits of U.S. dollars in banks located outside the United States.” However, you should emphasize that Eurodollars are not actual U.S. currencies deposited in a bank, but are bookkeeping entries on a bank’s ledger. These deposits are loaned to the Euro bank’s U.S. affiliate to meet liquidity needs, or the funds might be loaned to a corporation abroad that needs the loan denominated in U.S. dollars. Money does not normally leave the country of its origination; merely the ownership is transferred to another country. You might add that a dollar-denominated Eurobond is free of exchange rate risk for a U.S. investor, regardless of where it is issued. A foreign bond would be subject to this risk if it is not issued in the U.S. The reason is that the Eurobond pays interest in U.S. dollars, but the foreign bond pays interest in the currency of the country in which it was issued. Foreign bonds – bonds issued by a foreign company in a single country and in that country’s currency Gilts – British and Irish government securities London Interbank Offer Rate (LIBOR) – rate banks charge each other for overnight Eurodollar loans; often used as an index in floating rate securities Interest rate swap – agreement between two parties to periodically swap interest payments on a notional amount; normally one party pays a fixed rate and the other pays a floating rate A-4 CHAPTER 21 Currency swap – agreement between two parties to periodically swap currencies based on some notional amount 21.2. Foreign Exchange Markets and Exchange Rates Slide 21.5 Global Capital Markets Click on the web surfer icon to go to a web site that provides a wealth of information on international business Foreign exchange market – market for buying and selling currencies Foreign exchange market participants: -Importers and exporters -International portfolio managers -Foreign exchange brokers -Foreign exchange market markers -Speculators Video Note: “Foreign Exchange Market” looks at how Honda protects itself against changing exchange rates. Slide 21.6 Exchange Rates Click on the web surfer icon to go to the Pacific Data Center to see current and historical exchange rates. Slide 21.7 Example: Exchange Rates A. Exchange Rates Most currency trading is done with currencies being quoted in U.S. dollars. Cross rates and triangle arbitrage – implicit in exchange rate quotations is an exchange rate between non-U.S. currencies. The exchange rate between two non-U.S. currencies must equal the cross rate to prevent arbitrage. Slide 21.8 Slide 21.9 Work the Web Example Example: Triangle Arbitrage Example of Triangle Arbitrage: Suppose the Japanese Yen is quoted at 133.9 Yen per dollar and the South Korean Won is quoted at 666.0 Won per dollar. The exchange rate between Yen and Won is .1750 Yen per Won. The cross rate is (133.9 Yen/$) / (666.0 Won/$) = .201 Yen/Won CHAPTER 21 A-5 Buy low, sell high: 1) Have $1,000 to invest – buy yen = $1,000(133.9 Yen/$) = 133,900 Yen 2) Buy Won with Yen = 133,900 Yen / (.1750 Yen/Won) = 765,142.86 Won 3) Buy dollars with Won = 765,142.86 Won / (666 Won/$) = $1,148.86 4) Risk-free profit of $148.86 Lecture Tip: The opportunity to exploit a triangle arbitrage may appear to be an easy opportunity to make a quick profit. Point out that arbitrage opportunities are rare and that the transaction costs for small investors would outweigh any profit opportunity available. Types of Transactions Spot trade – exchange of currencies at immediate prices (spot rate) Forward trade – contract for the exchange of currencies at a future date at a price specified today (forward rate) Premium – if the forward rate > spot rate (based on $ equivalent or direct quotes), then the foreign currency is expected to appreciate and is selling at a premium Discount – if the forward rate < spot rate (based on $ equivalent or direct quotes), then the foreign currency is expected to depreciate and is selling at a discount Slide 21.10 Types of Transactions Lecture Tip: The late economist Milton Friedman provided a primer on exchange rates in the November 2, 1998 issue of Forbes magazine. He described three types of exchange rate regimes. Fixed rate or unified currency: “The clearest example is a common currency: the dollar in the U.S.; the euro that will shortly reign in the common market … the key feature of the currency board is that there is only one central bank with the power to create money.” Pegged exchange rate: “This prevailed in the East Asian countries other than Japan. All had national central banks with the power to create money and committed themselves to maintain the price of their domestic currency in terms of the U.S. dollar at a fixed level, or within narrow bounds – a policy they had been encouraged to A-6 CHAPTER 21 adopt by the IMF … In a world of free capital flows, such a regime is a ticking time bomb. It is never easy to know whether a [current account] deficit is transitory and will soon be reversed or is the precursor to further deficits.” Floating rates: “The third type of exchange rate regime is one under which rates of exchange are determined in the market on the basis of predominantly private transactions. In pure form, clean floating, the central bank does not intervene in the market to affect the exchange rate though it or the government may engage in exchange transactions in the course of its other activities. In practice, dirty floating is more common: The central bank intervenes from time to time to affect the exchange rate but does not announce in advance any specific value it will seek to maintain. That is the regime currently followed by the U.S., Britain, Japan and many other countries. 21.3. Purchasing Power Parity A. Absolute Purchasing Power Parity Absolute PPP indicates that a commodity should sell for the same real price regardless of the currency used Absolute PPP can be violated due to transaction costs, barriers to trade and differences in the product Slide 21.11 Absolute Purchasing Power Parity B. Relative Purchasing Power Parity The change in the exchange rate depends on the difference in inflation rates between countries. Relative PPP says that: E(St ) = S0[1 + (hF – hUS)]t assuming that rates are quoted as foreign currency per dollar. Currency appreciation and depreciation – Appreciation of one currency relative to another means that it takes more of the second currency to buy the first. For example, if the dollar appreciates relative to the yen, it means it will take more yen to buy $1. Depreciation is just the opposite. CHAPTER 21 A-7 Slide 21.12 Relative Purchasing Power Parity Slide 21.13 Example: PPP Lecture Tip: When asked, “Which is better – a stronger dollar or a weaker dollar?” most students answer a stronger one. While this makes imports relatively cheaper, it makes U.S. exports relatively more expensive. In general, consumers like a stronger dollar and producers, especially exporters, prefer a weaker one. At times, the government has spent considerable resources on making the dollar cheaper against the yen in an effort to reduce our trade deficit with Japan. Lecture Tip: The concept of relative PPP can be reinforced by considering an identical product that sells in both England and the U.S. at identical relative prices. If the inflation rate is 4% per year in the U.S., then the price for the product would increase by 4% over the year. However, if the inflation rate in England is 10%, the product price would increase by 10% in England over the year. Suppose the original price is $1 in the U.S. and the exchange rate is .5 pounds per dollar, so the product would cost .5 pounds in England. At the end of the year, the price in the U.S. would be 1(1.04) = $1.04 and the price in England would be .5(1.1) = .55 pounds. To prevent arbitrage, the exchange rate must change so that $1.04 is now equivalent to .55 pounds. In other words, the new exchange rate must be .55 pounds / $1.04 = .5288 pounds per dollar. The dollar has appreciated relative to the pound (it takes more pounds to buy $1) because of the lower inflation rate. 21.4. Interest Rate Parity, Unbiased Forward Rates, and the International Fisher Effect A. Covered Interest Arbitrage Slide 21.14 Covered Interest Arbitrage Slide 21.15 Example: Covered Interest Arbitrage A covered interest arbitrage exists when a riskless profit can be made by borrowing in the U.S. at the risk-free rate, converting the borrowed dollars into a foreign currency, investing at that country’s rate of interest, taking a forward contract to convert the currency back into U.S. dollars and repaying the loan. A-8 CHAPTER 21 Example: S0 = 2 Euro/$ F1 = 1.8 Euro/$ 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) B. RUS = 10% RE = 5% Borrow $100 at 10% Buy $100(2 Euro/$) = 200 Euro and invest at 5% (RE) At the same time, enter into a forward contract In 1 year, receive 200(1.05) = 210 Euro Convert to $ using forward contract; 210 Euro / (1.8 Euro/$) = $116.67 Repay loan and pocket profit: 116.67 – 100(1.1) = $6.67 Interest Rate Parity To prevent covered arbitrage: F1 1 RFC S 0 1 RUS Approximation: Ft = S0[1 + (RFC – RUS)]t Example: Suppose the Euro spot rate is 1.3 Euro / $. If the risk-free rate in France is 6% and the risk-free rate in the U.S. is 8%, what should the forward rate be to prevent arbitrage? Exact: F =1.3(1.06)/(1.08) = 1.28 Euro / $ Approximation: F = 1.3[1 + (.06 - .08)] = 1.274 Euro / $ Slide 21.16 Interest Rate Parity C. Forward Rates and Future Spot Rates Unbiased forward rates (UFR) –the forward rate, Ft, is equal to the expected future spot rate, E[St]. That is, on average, the forward rate neither consistently underestimates nor overestimates the future spot rate. That is, Ft = E[St] Slide 21.17 Unbiased Forward Rates D. Putting It All Together PPP: E[S1] = S0[1 + (hFC – hUS)] CHAPTER 21 A-9 IRP: F1 = S0[1 + (RFC – RUS)] UFR: F1 = E[S1] Uncovered interest parity (UIP) – combining UFR and IRP gives: E[S1] = S0[1 + (RFC – RUS)] E[St] = S0[1 + (RFC – RUS)]t Slide 21.18 Uncovered Interest Parity The International Fisher Effect – combining PPP and UIP gives: S0[1 + (hFC – hUS)] = S0[1 + (RFC – RUS)] so that hFC – hUS = RFC - RUS and RUS – hUS = RFC – hFC The IFE says that real rates must be equal across countries. Slide 21.19 International Fisher Effect 21.5. International Capital Budgeting Slide 21.20 Overseas Production: Alternative Approaches A. Method 1: The Home Currency Approach This involves converting foreign cash flows into the domestic currency and finding the NPV. Slide 21.21 Home Currency Approach B. Method 2: The Foreign Currency Approach In this approach, we determine the comparable foreign discount rate, find the NPV of foreign cash flows, and convert the NPV to dollars. Slide 21.22 Foreign Currency Approach Example: Pizza Shack is considering opening a store in Mexico City, Mexico. The store would cost $1.5 million or 16,361,250 pesos to open. Pizza Shack hopes to operate the store for two years and then sell it at the end of the second year to a local franchisee. Cash flows are expected to be 1,000,000 pesos in the first year and A-10 CHAPTER 21 25,000,000 pesos the second year. The spot exchange rate for Mexican pesos is 10.9075. The U.S. risk-free rate is 4%, and the Mexican risk-free rate is 7%. The required return (U.S.) is 12%. 1. The home currency approach Using UIP: E[S1] = 10.9075[1 + (.07 - .04)] = 11.2347 E[S2] = 10.9075[1 + (.07 - .04)]2 = 11.5718 Year 0 1 2 Cash Flow (pesos) -16,361,250 1,000,000 25,000,000 E[St] 10.9075 11.2347 11.5718 Cash Flow ($) -1,500,000.00 89,009.94 2,160,424.48 NPV at 12% = 301,750.33* 2. The foreign currency approach Using the IFE to get the inflation premium (7 – 4) = hFC – hUS = 3%. Factor this into the US discount rate to get the Mexican discount rate: (1.12*1.03 – 1) = 15.36%. NPV of peso cash flows at 15.36% = 3,291,393.79 pesos NPV in dollars = 3,291,393.79 / 10.9075 = 301,755.10* *Note that the two approaches will produce exactly the same answers if the exact formulas are used for each of the parity equations instead of the approximations. C. Unremitted Cash Flows Not all cash flows from foreign operations can be remitted to the parent company. Ways foreign subsidiaries remit funds to the parent: 1. dividends 2. management fees for central services 3. royalties on trade names and patents Blocked funds – funds that cannot currently be remitted to the parent CHAPTER 21 A-11 Ethics Note: The following case may be used as a class example to expose the class to the ethical problems involving shell corporations that attempt to conduct business on the fringe of violating international law. In February 1989, the West German Chemical Industry Association suspended the membership of Imhausen Chemie, a major West German chemical manufacturer in response to the charge that Imhausen supplied Libya with the plant and technology to produce chemical weapons. In June 1990, the former Managing Director of Imhausen was convicted of tax evasion and violating West Germany’s export control laws. In November 1984, a shell corporation had been established in Hong Kong to conceal actual ownership of the chemical operations. In April 1987, a subsidiary of the shell corporation was established in Hamburg, West Germany for the purpose of acquiring materials from Imhausen, thus circumventing German export laws. A shipping network was established to fake end-use destinations and sell to Libya. Reports later surfaced that Libya had constructed a chemical weapons factory. Imhausen did not deny the plant’s existence but Imhausen, as well as the government of Libya, claimed that the plant was being used for the manufacturer of medicinal drugs. International treaties forbade the use of chemical and biological weapons but did not restrict chemical weapons facility construction. The international community faced a further dilemma, as aerial observation could not distinguish between a weapons plant and a pharmaceutical plant. Additionally, such plants could easily be switched to legitimate use in a few days. While construction of the plant did not violate German or international law, the ease of conversion from legitimate use to weapons production raised questions regarding the technical knowledge transferred by Imhausen. You might question the class as to Imhausen’s responsibility in the ultimate use of the plant, despite the fact that the development of the shell corporation was a positive NPV investment. Slide 21.23 Repatriated Cash Flows 21.6. Exchange Rate Risk A. Short-Run Exposure A-12 CHAPTER 21 Exchange rate risk – the risk of loss arising from fluctuations in exchange rates A great deal of international business is conducted on terms that fix costs or prices while at the same time calling for payment or receipt of funds in the future. One way to offset the risk from changing exchange rates and fixed terms is to hedge with a forward exchange agreement. Another hedging tool is to use foreign exchange options. An option will allow the firm to protect itself against adverse exchange rate movements and still benefit from favorable exchange rate movements; however, this has an added premium cost. Slide 21.24 Short-Run Exposure Lecture Tip: There were several earnings warnings for the third quarter of 2000 by multinational firms. One of the biggest reasons cited was the weak Euro relative to the dollar. A strong dollar makes our products more expensive in Europe and reduces the sales level by limiting the number of people that can afford to buy the products. The exact opposite situation occurred in 2008, as the weak dollar helped US multinationals. B. Long-Run Exposure Long-run changes in exchange rates can be partially offset by matching foreign assets and liabilities, inflows and outflows. Slide 21.25 Long-Run Exposure C. Translation Exposure Slide 21.26 Translation Exposure U.S. based firms must translate foreign operations into dollars when calculating net income and EPS. Problems: 1. What is the appropriate exchange rate to use for translating balance sheet accounts? 2. How should balance sheet accounting gains and losses from foreign currency translation be handled? FASB 52 requires that assets and liabilities be translated at the prevailing exchange rates. Translation gains and losses are accumulated in a special equity account and are not recognized in CHAPTER 21 A-13 earnings until the underlying assets or liabilities are sold or liquidated. D. Managing Exchange Rate Risk For large multinational firms, the net effect of fluctuating exchange rates depends on the firm’s net exposure. This is probably best handled on a centralized basis to avoid duplication and conflicting actions. Slide 21.27 Managing Exchange Rate Risk 21.7. Political Risk Blocking funds and expropriation of property by foreign governments are among routine political risks faced by multinationals. Terrorism is also a concern. Financing the subsidiary’s operations in the foreign country can reduce some risk. Another option is to make the subsidiary dependent on the parent company for supplies; this makes the company less valuable to someone else. Slide 21.28 Political Risk 21.8. Summary and Conclusions Slide 21.29 Quick Quiz Slide 21.30 Ethics Issues