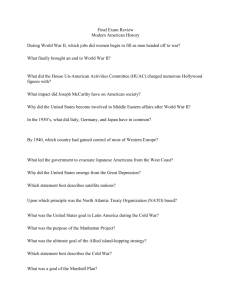

Chapter 29 Overview - Bishop McGann

advertisement

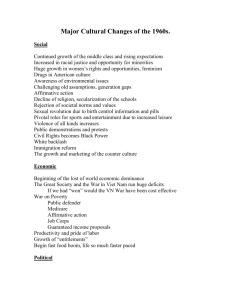

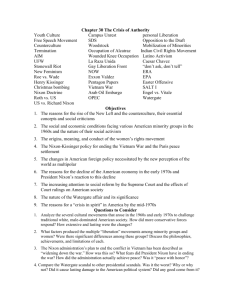

CHAPTER 29 From Camelot to Watergate CHAPTER OVERVIEW Kennedy in Camelot. Kennedy made a show of presenting himself to the public as young, vigorous, athletic, and intellectual. That carefully constructed image, however, was misleading. Kennedy was no intellectual. He had a myriad of health problems, for which he took heavy doses of painkillers and amphetamines. In addition, he engaged in a reckless series of extramarital sexual adventures. Members of his administration prided themselves on being the best and the brightest. Like the president himself, his administration failed to live up to the image it fashioned for itself. The Cuban Crises. Kennedy believed that his chief task was to stop the spread of communism. In a departure from Eisenhower’s reliance on America’s nuclear deterrent, Kennedy proposed to challenge communist aggression wherever it occurred. Not long after taking power, he authorized an invasion of Cuba by Cuban exiles. The landing at the Bay of Pigs in April, 1961 was a complete fiasco. The affair exposed the United States to all the criticism a straightforward assault would have, and it failed to overthrow Castro. Castro moved toward the Soviet orbit. In June, 1961, Kennedy and Khrushchev met in Vienna, where Khrushchev blustered about taking West Berlin. In August, Khrushchev ordered the construction of the Berlin Wall. Both sides resumed nuclear testing and built up massive nuclear arsenals. Kennedy also instructed the CIA to initiate “massive activity” against Castro’s regime, which included attempts to assassinate the Cuban dictator. In October, 1962, Khrushchev placed Soviet troops, bombers, and nuclear missiles in Cuba. Kennedy forced a showdown by ordering the United States Navy to halt the shipment of offensive weapons to Cuba. The world held its breath for several days until Khrushchev finally backed down. Although Kennedy’s supporters regarded this as Kennedy’s finest hour, in retrospect it appears that he overreacted. Both Kennedy and Khrushchev seem to have been sobered by the missile crisis. However, the humiliation Khrushchev suffered contributed to his overthrow by hardliners two years later. The Vietnam War. After the French defeat in 1954, the parties agreed to general elections in 1956. Fearing that Ho Chi Minh would defeat him, Ngo Dinh Diem, the American-backed leader of South Vietnam, cancelled the election, and, with American assistance, attempted to build a new nation. Viet Minh units that remained in the south (later known as Viet Cong) formed secret cells and waited. By the late 1950s, they had gained strength and become more militant. In May, 1959, Viet Cong guerrillas began an insurgency that gave them control of large sections of the countryside. As a senator, Kennedy had backed Diem; moreover, he wanted to demonstrate his toughness after the Bay of Pigs. Thus, he began to expand the American commitment to Vietnam. By 1963, there were over 16,000 American military personnel in South Vietnam, and 120 American soldiers had been killed. In spite of that effort, Diem’s regime was faltering by 1963. A devoted Catholic, Diem cracked down on Buddhists, who resisted. Kennedy sent word to dissident Vietnamese generals that he would support them if they ousted Diem. The generals took power on November 1 and killed Diem. Some have argued that Kennedy would not have continued the course on which he embarked. The evidence indicates otherwise. “We Shall Overcome”: The Civil Rights Movement. Kennedy initially approached the question of race with extreme caution. His narrow victory in 1960 depended on the votes of both African Americans and white southerners. In February, 1960, four black students staged a “sit-in” at a Woolworth lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina. This act of defiance inspired similar actions across the South. Blacks and whites tested federal regulations prohibiting discrimination on interstate transportation in the “freedom rides” of 1961. The protracted struggle gradually broke down legal and racial barriers in the South. Some African Americans became impatient with the pace of change, and black nationalism became a potent force. Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Black Muslims, called for the establishment of separate black and white nations and rejected nonviolence. In 1963, King and the SCLC staged massive demonstrations in Birmingham, during which King was arrested. In jail, King wrote his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” The brutal response to the demonstrations in Birmingham pushed Kennedy to change his policy and lend his support to a modest civil rights bill. When the bill stalled in Congress, civil rights groups organized a massive demonstration in Washington, at which King gave his “I Have a Dream” speech. Tragedy in Dallas: JFK Assassinated. While visiting Dallas, Texas, on November 22, 1963, Kennedy was assassinated. Police apprehended Lee Harvey Oswald, and a mass of evidence linked him to the assassination. Before he could be brought to trial, he was murdered by Jack Ruby. An investigation headed by Chief Justice Warren concluded that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone, and although there is little evidence to support the theory that Oswald was part of a larger conspiracy, many doubted the Warren Commission’s conclusion. Lyndon Baines Johnson: the Great Society. From 1949 until his election as vice-president, Johnson served in the Senate, for most of that time as Senate Democratic leader. A master of manipulation, Johnson could use both heavy-handed and subtle approaches to gain his objectives. He modeled himself after Franklin Roosevelt and had a commitment to social welfare legislation. In this, he differed markedly from Kennedy. Kennedy’s inaugural address made no mention of domestic policy. When Congress blocked his modest domestic agenda, Kennedy reacted mildly. Johnson sought power because he “wanted to use it.” On assuming office, he exploited the atmosphere surrounding Kennedy’s assassination to push an expanded version of Kennedy’s legislative agenda through Congress. Johnson pushed through passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, an expanded version of Kennedy’s bill. Aspiring to be a great reformer in the tradition of FDR, Johnson declared war on poverty in America and set out to create a “Great Society” in which poverty would no longer exist. The Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 created the Job Corps, provided for the education for small children, and established work study programs for college students. After his sweeping victory over the unabashedly conservative Barry Goldwater in 1964, Johnson pressed for further reforms. Under his leadership, Congress passed the Medicare Act (1965), the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (1965), and the Voting Rights Act (1965). Other programs provided support for the arts and for scientific research, highway safety, crime control, slum clearance, clean air and water, and the preservation of historic sites. While the scope and intent of the Great Society programs were truly remarkable, in practice they often failed to have the impact the president had desired. New Racial Turmoil. In spite of significant gains, radicalism won more and more converts among black activists in the 1960s. SNCC, an organization born out of the sit-ins and committed to integration, rejected integration and interracial cooperation after experiencing violence and intimidation while trying to register black voters and organize schools for black children in the Deep South. The election of Stokely Carmichael as chairman of the SNCC indicated the growing strength of “Black Power.” Urban riots also manifested black impatience, frustration, and despair. Rioting, along with demands by advocates of Black Power for separate schools, generated a white backlash. From the “Beat Movement” to Student Radicalism. The notion of a “conformist” generation of the 1950s yielding to an “activist” generation of the 1960s is overdrawn. The roots of the 1960s were firmly planted in the 1950s. One can find this in writers such as J. D. Salinger, author of Catcher in the Rye (1951) and Beat authors, including Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac. In the 1960s, hippies, turned off by the modern world, sought refuge from it in communes, drug use, and mystical religion. Students in the 1960s became frustrated by the persistence of racism and poverty in the richest country in the world. Hard-line anticommunism, in the age of atomic weapons, seemed suicidal. Such sentiments drew students to SDS, the goals of which were set forth in its Port Huron Statement of 1962. Controversy over political organizing on campus gave rise to the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley. Johnson’s escalation of the war in Vietnam turned student radicalism from a phenomenon on college campuses into a mass political movement. Johnson Escalates the War. After Diem’s assassination, the situation in South Vietnam continued to deteriorate. In spite of a series of military coups, Johnson believed that he had no choice but to support the regime in South Vietnam. Alarmed over the growing successes of the Vietcong, President Johnson engaged in a gradual buildup of American forces in Vietnam. Johnson used the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution to justify escalation of the United States’ role in Vietnam. By the middle of 1968, more than 538,000 Americans were engaged in a full-scale war that Congress had never declared. The Election of 1968. Opposition to the war grew; it was particularly vehement on college campuses. In 1967, Senator Eugene McCarthy, a Democrat from Minnesota, launched a bid for his party’s nomination based on his opposition to the war. The Tet Offensive in 1968 and news that the administration was considering a request to dispatch an additional 206,000 American troops to Vietnam dramatically altered the balance of power in the Democratic Party. McCarthy won 42 percent of Democrats who voted in the New Hampshire primary. After McCarthy’s strong showing, former Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy entered the Democratic race. After much soul-searching, Johnson announced that he would not seek reelection. Vice-President Hubert H. Humphrey then entered the contest. McCarthy and Kennedy each won primaries. After winning a narrow victory in California, Kennedy was assassinated. The Democratic Party’s convention in Chicago, racked by great turmoil, nominated Humphrey. Former Vice-President Richard M. Nixon won the Republican nomination and chose Spiro T. Agnew of Maryland as his running mate. Although far behind in the early stages of the campaign, Humphrey gained ground: Nixon won the 1968 election with a popular margin of less than 500,000 votes. The Independent candidate, George Wallace of Alabama, ran an anti-black, anti-intellectual, and hawkish campaign. He received 46 electoral votes and about 13.5 percent of the popular vote. Nixon as President: “Vietnamizing” the War. Nixon projected the image of calm, deliberate statesmanship. He considered his major challenge to be finding an acceptable solution to the war in Vietnam. As a candidate, he pledged to end the war on “honorable terms.” Toward that end, Nixon proposed to build up the South Vietnamese armed forces, so that American troops could withdraw without the communists overrunning the South (Vietnamization). However, the United States had failed for 15 years to make the South Vietnamese capable of defending themselves. At home, the peace movement grew in size and militancy. Nixon announced a phased withdrawal of American troops. Nevertheless, the war continued, and the human costs of a stalemated war, along with revelations of atrocities committed by American troops at My Lai, gave new momentum to the peace movement. The Cambodian “Incursion.” In April, 1970, Nixon announced the withdrawal of another 150,000 American soldiers and declared that Vietnamization was proceeding ahead of schedule. One week later, he authorized an incursion into Cambodian territory to destroy communist bases there. The nation’s college campuses erupted in protest. At Kent State University in Ohio, after days of demonstrations, National Guardsmen killed four students. State police killed two students at Jackson State University in Mississippi. A wave of student actions closed hundreds of colleges and universities across the nation. Faced with this turmoil, the president increased the pace of troop withdrawals, but escalated American bombing raids over North Vietnam. He also ordered the mining of Haiphong and other northern ports. Détente with Communism. In the midst of his aggressive actions in Vietnam, Nixon and his foreign policy advisor, Henry Kissinger, embarked on an epic diplomatic venture. Rather than treating communism as a monolith, Nixon and Kissinger dealt with Russia and China as separate powers. In February, 1972, Nixon became the first American president to visit the People’s Republic of China. He followed this unprecedented move by meeting with the Soviet leadership in Moscow in May. Nixon returned from Moscow with a treaty calling for the limiting of strategic arms (SALT). This new policy, known as détente, meant a relaxation of tensions. It enabled the United States to play off the two communist superpowers against each other. By October, 1972, Kissinger had negotiated a draft settlement with the North Vietnamese. Shortly before the election, he announced that “peace was at hand.” Nixon in Triumph. Nixon won a landslide victory over the Democratic nominee, George McGovern, in 1972. McGovern’s campaign had been hampered by factionalism within his party, his bumbling oratorical style, and his tendency to advance poorly thought-out proposals. Nixon blew huge holes in the Democratic coalition. He won in the South and among northern bluecollar workers. With his anti-inflationary policies, détente, and the prospects of peace in Vietnam, Nixon appeared to be a successful and powerful president. However, Kissinger’s agreement with the North Vietnamese fell apart when Nguyen Van Thieu, South Vietnam’s president, refused to sign it. After attempting to extract more favorable terms from the North Vietnamese by ordering extensive bombing of the North, Nixon finally reached a settlement with the North Vietnamese in January, 1973. The United States lost more than 57,000 lives and spent more than $150 billion in Vietnam. Domestic Policy Under Nixon. The most serious issue Nixon faced was the high rate of inflation caused primarily by the large military outlays of the Johnson administration and its refusal to raise taxes. Nixon balanced the 1969 federal budget, and the Federal Reserve Board raised interest rates. Prices continued to rise, however, and in 1970, Congress passed legislation giving the president power to regulate wages and prices. Although Nixon did not favor this legislation, he implemented it the following year. Phase II of his anti-inflationary policies involved the creation of a pay board and a price commission to limit wage and price increases after the freeze ended. Inflation slowed but did not stop. Nixon did not pursue a rigidly conservative course. He proposed a bold plan for a minimum income for poor families, which alarmed his conservative supporters and failed to pass Congress. The president signed the Clean Air Act of 1970 and legislation creating the Environmental Protection Agency. On the other hand, Nixon’s southern strategy sought the support of southern conservative Democrats by pulling back on the federal government’s commitment to school desegregation and by appointing, for the most part, conservative justices to the Supreme Court. After his triumphant reelection and the withdrawal of American troops from Vietnam, Nixon attempted to change the direction in which the nation had been moving for decades. While strengthening the presidency vis-a-vis Congress, he sought to decentralize his administration by returning various functions to state and local governments. He also set out to reduce the role of government in people’s lives. These aims brought him into conflict with liberals of both parties. In an effort to combat inflation, Nixon set a limit on federal spending. To keep within that limit, he impounded (refused to spend) funds Congress had appropriated. Critics began to grumble about an “imperial presidency.” The Watergate Break-in and Cover-up. On March 19, 1973, James McCord, an employee of the Committee to Re-Elect the President (CREEP) and an accused burglar, wrote a letter to Judge John Sirica revealing that high-level Republican officials had prior knowledge of the break-in at the Democratic headquarters in the Watergate Hotel in Washington, D.C., on June 17, 1972. Nixon denied the involvement of anyone in the White House. Soon after, however, Jeb Stuart Magruder, head of CREEP, and John W. Dean III, legal counsel to the president, admitted their involvement. Subsequent to these revelations, Nixon dismissed Dean; and most of the president’s closest advisers, including H.R. Haldeman, John Ehrlichman, and Richard Kleindienst, resigned. Dean then charged that the president had participated in an attempted cover-up of the affair. Subsequent grand jury investigations and the findings of a Senate investigation headed by Sam Ervin of North Carolina revealed that the president had acted to obstruct investigations into the matter. Investigations also revealed that the president and his staff had abused the powers of their offices and orchestrated a vast array of illegal and unethical practices during the election campaign. The Senate Watergate committee learned of the existence of tapes Nixon had made of White House conversations. Nixon refused to surrender these tapes to the committee. This led to calls for his resignation, even impeachment. In response, Nixon appointed a special prosecutor to investigate the affair. Archibald Cox, the prosecutor, soon aroused the president’s ire by seeking access to records, including the tapes. Nixon ordered Cox fired. Rather than dismiss Cox, Attorney General Elliot Richardson and his deputy, William Ruckelshaus, resigned. Robert Bork, the solicitor general, carried out Nixon’s order. The “Saturday Night Massacre” outraged the public. The House Judiciary Committee considered impeachment. Nixon backed down; he named a new prosecutor, Leon Jaworski, and turned the tapes over to Sirica. However, some of the tapes were missing, and an important section of another had been deliberately erased. Vice-President Agnew, champion of law and order, resigned after pleading nolo contendere to charges of accepting bribes and committing tax fraud while serving in public office in Maryland. Nixon nominated, and Congress confirmed, Gerald Ford, a congressman from Michigan, as vice-president. The Judgment on Watergate: “Expletive Deleted.” In March, 1974, a federal grand jury indicted Haldeman, Ehrlichman, Mitchell, and four other White House aides on charges of conspiracy to obstruct justice in the Watergate investigations. Nixon was named as an “unindicted co-conspirator.” Nixon released edited transcripts of the White House tapes to the press. Not only were the tapes incriminating, they also exposed a sordid side of Nixon’s character. In the summer of 1974, the House Judiciary Committee, in televised proceedings, voted to adopt three articles of impeachment against the president. Nixon was charged with obstructing justice, abusing the powers of his office, and failing to comply with the committee’s subpoenas. On the eve of the debates, the Supreme Court ruled that Nixon had to turn over 64 additional tapes to the special prosecutor. The tapes proved conclusively that Nixon had been in on the cover-up from its earliest stages. Virtually all of his remaining support in Congress evaporated. The Meaning of Watergate. Facing certain impeachment and conviction, on August 9, 1974, Nixon became the first president to resign. Gerald Ford became president. Shortly after taking office, Ford pardoned Nixon for any crimes he had committed in office. Nixon’s policy of détente marked an easing of cold war tensions; the failure of his interventionist domestic policies signaled growing disillusionment with Johnson’s Great Society. Vocabulary/Key Terms Bay of Pigs Beat Generation Berlin Wall Civil Rights Act of 1964 Cuban Missile Crisis Détente Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Great Society Gulf of Tonkin Resolution Medicare Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT) Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) Tet Offensive United States v. Richard M. Nixon Voting Rights Act of 1965 Watergate scandal Vietnamization