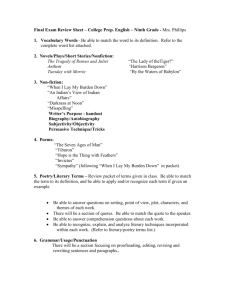

AP Lit Summer 15-16

advertisement

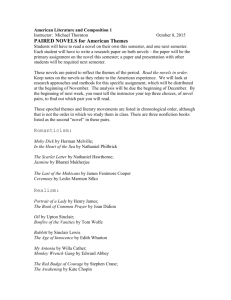

Advanced Placement Literature Composition Summer Enrichment Assignments 2015-16 Welcome to Advanced Placement Literature and Composition. The purpose of this class is to prepare you for the AP test in May; however, the greater goal is to develop reading, writing, and analytical skills that will help you in college and beyond. We will be reading from a variety of eras, authors, and genres—specifically, novels, novellas, short stories, drama, and poetry. We will learn how to analyze the methods and devices used in literature and how to write a literary analysis paper. Reading complex texts*: It is essential that students focus on the close, sustained analysis of complex texts. Close, analytic reading stresses engaging with a text of sufficient complexity directly and examining its meaning thoroughly and methodically, encouraging students to read and reread deliberately. Directing student attention on the text itself empowers students to understand the central ideas and key supporting details. It also enables students to reflect on the meanings of individual words and sentences; the order in which sentences unfold; and the development of ideas over the course of the text, which ultimately leads students to arrive at an understanding of the text as a whole. Close, analytic reading entails the careful gathering of observations about a text and careful consideration about what those observations taken together add up to — from the smallest linguistic matters to larger issues of overall understanding and judgment. (*adapted from the PARCC Framework) ASSIGNMENT: READ, ANNOTATE, LIST VOCABULARY, LOG Your responsibility this summer is to read the listed novels, annotating as you go. (See attached handout on Annotation to guide your method and your focus—annotation is expected throughout the class as it is an essential college skill to develop.) We have provided some preliminary reading notes to enhance your understanding of these classic texts. You are required to read at least 2 novels this summer: The Stranger, Albert Camus Great Expectations, Charles Dickens (1861) OR Jane Eyre, Charlotte Bronte (1847) OR The Scarlet Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne (1850) We recommend that you also keep a list of unfamiliar vocabulary and definitions. (There is a fair amount of vocab on the AP exam—and the words come from literature.) These activities will help you prepare for the class by looking at some of the characteristics of the literature that you will be reading all year long in AP Literature. Your goal is to create a written trail of key reminders to help you remember, understand and analyze what you have read. You will be writing about these novels once school begins. Although these novels are challenging—and you may be attempted to take shortcuts—restrain yourself. We have seen the movies, as well as many online sources. Allow yourself the time needed to do ALL the reading and annotating—you will benefit when it comes time to be tested. (In other words, DO NOT leave this project until August. These are key novels, ones you will rely on for responding to AP prompts. Please contact me if you have questions (mabeshaus@northlandprep.org). Tentative 2015-16 Reading List AP English Literature and Composition Summer Reading Great Expectations, Charles Dickens (1861) OR Jane Eyre, Charlotte Bronte (1847) OR The Scarlet Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne (1850) The Stranger, Albert Camus Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen Frankenstein, Mary Shelley A Doll’s House, Henrik Ibsen (in Perrine) Read aloud Beowulf, Seamus Heaney, Trans. Read aloud (class set) Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck To Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee Catcher in the Rye, J. D. Salinger Twelfth Night, William Shakespeare (or alternative Shakespearean drama) Read aloud Mrs. Dalloway, Virginia Woolf The Hours, Michael Cunningham Othello, William Shakespeare (in Perrine) Read aloud Ceremony, Leslie Marmon Silko The Glass Castle, Jeanette Walls Assorted informational texts, short stories and poetry Although some works are available online, I highly recommend acquiring a copy of these texts (except those “in Perrine”), as it is difficult to curl up with a “good” book (and annotate) when your computer is involved (unless, of course, you are the proud owner of an iPad or Kindle). A very limited number of these novels are also available from my lending library. First come, first serve. NOTES ON THE NOVELS The Stranger, Albert Camus Albert Camus has associated his work with absurdism, a relative of existentialism. According to Henderson and Brown, absurdism is A philosophical attitude pervading much of modern drama and fiction, which underlines the isolation and alienation that human beings experience, having been thrown into what absurdists see as a godless universe devoid of any religious, spiritual, or metaphysical meaning. Conspicuous in its lack of logic, consistency, coherence, intelligibility, and realism, the literature of the absurd depicts the anguish, forlornness, and despair inherent in the human condition. Counter to the rationalist assumptions of traditional humanism, absurdism denies the existence of universal truth or value. (Henderson and Brown) Camus used his writing to reveal this philosophy of the absurd. As Alan Gullette explains: In his novel The Stranger, Albert Camus gives expression to his philosophy of the absurd. The novel is a first-person account of the life of M. Meursault from the time of his mother's death up to a time evidently just before his execution for the murder of an Arab. The central theme is that the significance of human life is understood only in light of mortality, or the fact of death; and in showing Meursault's consciousness change through the course of events, Camus shows how facing the possibility of death does have an effect on one's perception of life. THEMATIC FOCUS: Given this brief introduction to absurdism, look for evidence of this philosophy in every chapter of the novel. Works Cited Gullette, Alan. “Death and Absurdism in Camus’s The Stranger.” University of Tennessee-Knoxville, March 1979. Web. May 2011. Henderson, Greig E. and Christopher Brown, “Absurdism.” Glossary of Literary Theory. University of Toronto, 1997. Web. May 2011. Great Expectations, Charles Dickens Some insights into the novel: Length. Great Expectations is one of the longest works we read (thus, the summer assignment). In fact, Dickens was essentially paid by the word: his novels were serialized, meaning they were published a chapter at a time with the hopes that readers would be sufficiently intrigued to buy the next chapter. Language. This novel is also one of the oldest works we read, which means that sometimes the language may appear unfamiliar and archaic. Don’t be lazy—use the appropriate reference source to find out what the strange words mean, and add these words to your vocab list. (Weird vocabulary is an AP Lit exam specialty.) Social Critique/Humor. Dickens used his novels as a means of critiquing the society in which he lived—often in humorous ways. Be sensitive to these humorous moments: detecting the subtle humor will greatly increase your enjoyment of and appreciation for these novels. Bildungsroman. A Bildungsroman is, most generally, the story of a single individual's growth and development within the context of a defined social order. The growth process, at its roots a quest story, has been described as both "an apprenticeship to life" and a "search for meaningful existence within society." To spur the hero or heroine on to their journey, some form of loss or discontent must jar them at an early stage away from the home or family setting. The process of maturity is long, arduous, and gradual, consisting of repeated clashes between the protagonist's needs and desires and the views and judgments enforced by an unbending social order. Eventually, the spirit and values of the social order become manifest in the protagonist, who is then accommodated into society. The novel ends with an assessment by the protagonist of himself and his new place in that society. (Hader) THEMATIC FOCUS: For each chapter, be on the lookout for evidence of Pip’s growth and development. Work Cited Hader, Susan. “The Bildungsroman Genre: Great Expectations, Aurora Leigh, and Waterland.” The Victorian Web. 2005. Web. May 2011. The Scarlet Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne (1850) (see Great Expectations notes above) “Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter is a wonderful text to couple with the teaching of Transcendentalism. The protagonist, Hester Prynne, displays many acts of civil disobedience throughout the course of the novel, and Hawthorne often criticizes the Puritan society that punishes her so harshly. The lessons from this novel relate very closely to the ideas espoused by the great transcendental thinkers—civil disobedience, self-reliance, and nature as a reflection of God. In addition to using Transcendentalism as a historical context and lens for the novel,” “mine” this novel for symbols. In other words, be on the look out for symbols; there are many. (Clayton) Finally, consider the following essential questions: How do varying levels of religious influence on governments dictate moral and ethical law? How does a society’s definition of “sin” influence/affect the individual? How do hypocrisy, conformity, vengeance, and forgiveness affect the characters? How do these same forces affect others? Jane Eyre, Charlotte Brontë (1847) (see Great Expectations notes above) Select Notes from Edsitement: Introducing Jane Eyre: An Unlikely Victorian Heroine Introduction When Charlotte Brontë set out to write the novel Jane Eyre, she was determined to create a main character who challenged the notion of the ideal Victorian woman, or as Brontë was once quoted: "a heroine as plain and as small as myself" (Gaskell, Chapter XV). Brontë's determination to portray a plain yet passionate young woman who defied the stereotype of the docile and domestic Victorian feminine ideal most likely developed from her own dissatisfaction with domestic duties and a Victorian culture that discouraged women from having literary aspirations. . . . Contemplating Brontë's position and desire for literary achievement in that context, students will consider why she felt compelled to write Jane Eyre and then to publish it under the male pseudonym Currer Bell. Background During an era when etiquette guides circulated freely, empire waists gave way to tiny-waisted corsets, and tea parties grew in popularity, it might seem incongruous that realistic novels would set the Victorian literary trend. Perhaps the socially conscious novel may have been a result of the belief of the rising middle class of Victorian England in the possibility for change, since they had witnessed such economic changes in their lifetimes. Works such as Charles Dickens' Hard Times, George Eliot's Middlemarch and Charlotte's Brontë's own sister Emily's Wuthering Heights featured female characters that represented trapped and repressed Victorian women marrying for the wrong reasons, disillusioned with family life, and relying on their physical beauty as a means to gain attention and advancement. And then, along came the character Jane Eyre: physically uninteresting yet passionate and intense in her desire to express her emotions and thoughts. It is no wonder that Currer Bell's (Charlotte Brontë's pseudonym) novel was considered groundbreaking and bold. Jane is a heroine battling the same societal limitations as her literary counterparts, but her raw narrative voice never fails to expose her Romantic sensibilities, psychological depth, and her adamant desire to stay true to herself. ANNOTATING TEXTS What to Annotate Literary Elements Character Setting Point of View Plot Theme Literary Devices (apply to novels, short stories, drama, poetry) Connotation/Denotation (Diction) Metaphor/Simile Personification Apostrophe Metonomy/Synecdoche Symbol Allegory Paradox Overstatement/ Hyperbole Understatement Irony Allusion Imagery Anaphora Polysyndeton/Asyndeton Parallelism Analogy Repetition Apposition/Variation Rhetorical question Oxymoron Alliteration Assonance/Consonance Onomatopoeia Cacaphony/Euphony Phonetic intensives Common Literary Themes Man versus self (alienation, arrogance, growth and initiation) Man versus man (human relations) Man versus Nature Man versus the gods Man versus society How to Annotate Read actively. Take advantage of the cues provided by the text: title, author, publication date, cover notes, and table of contents. Read with a pen or pencil in hand to underline important and/or interesting passages and to make notes in the margins. You may also choose to annotate passages on sticky notes marking important notable pages. The goal is active, involved reading: Reading and constructing meaning from a text is a complex and active process; one way to help students slow down and develop their critical analysis skills is to teach them to annotate the text as they read. What students annotate can be limited by a list provided by the teacher or it can be left up to the student’s discretion. Suggestions for annotating text can include labeling and interpreting literary devices (metaphor, simile, imagery, personification, symbol, alliteration, metonymy, synecdoche, etc.); labeling and explaining the writer’s rhetorical devices and elements of style (tone, diction, syntax, narrative pace, use of figurative language, etc.); or labeling the main ideas, supportive details and/or evidence that leads the reader to a conclusion about the text. Of course, annotations can also include questions that the reader poses and connections to other texts that reader makes while reading. (Greece Central School District, www.greece.k12.ny.us/ instruction/ ELA/6-12/ Reading/Reading%20Strategies/annotating%20a%20text.htm) Watch for main ideas and for the way the ideas are organized. Also, underline any new vocabulary, adding definitions as needed. You will be graded on your marginalia. Remember there is no one right way to annotate: create a system that works for you, complete with your own symbols and shortcuts (but keep track of your own code). ***** Highlighting or Underlining (a passive activity) o Must be selective to be effective: mark only those words, phrases or sentences worthy of further consideration; pertinent to your position or area of study Interesting passages—writing that catches your attention Key words of the discipline or topic Sentences Quotable, making significant points in well-worded phrasing Establish or shift an argument Evidence or proof Convincing (or questionable) conclusions Examples that help analyze or might be worth referring to Challengeable comments—questionable positions or unsupported arguments o To ensure effectiveness, add a comment in margin explaining reasoning behind highlighting; that is, what it is about the section that caught your eye Marginal Notes (Annotation): making use of text margins or sticky notes (a more activity, thoughtprovoking activity encouraging you to get more involved in the text) o Define words o Ask critical questions o Clarify complex sentences by restating or rephrasing o Interpret unclear words, sentences, ideas o Evaluate: respond with reasoned commentary o Trace a particular motif o Note areas of confusion (?) o Be aware of patterns (repeated themes or patterns) o Make notes about your ideas (MINE). For example, something you read makes you angry—or otherwise passionate—record your response so you remember how the text made you feel—and why Circling or Dog-Earring important pages (or using a sticky note) Brackets to block our several lines (or even a paragraph) of key writing Asterisks: use one or more * to point to important passages/points. Using arrows provides a similar indicator Summary Notes o List page numbers inside covers or in notebook o Particularly useful for tracing a certain theme, character, symbol, particular rhetorical strategy, etc. (especially if you are reading with a specific assignment in mind)