Innovations Project Report - National Centre for Computer Animation

advertisement

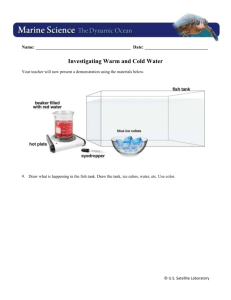

Sir Flambio Foplin 2D Animation Innovations Project Report Clare Williams BA (Hons) Computer Visualisation and Animation Level H Spring 2005 1 Index 1. Introduction 1.1 Aim Page 4 1.2 Product Page 4 1.3 Introduction Page 4 1.4 The Project as an Innovation Page 5 1.5 Choosing the piece Page 5 1.6 Background to the Character Page 6 1.7 Synopsis Page 6 1.8 The difference between 3D & 2D animation Page 6 2. The Industry Pipeline Page 7 3. The Method Page 9 3.1 Calculating the Timing Page 9 3.2 The Dope sheet Page 11 3.3 Key Animation Page 11 3.4 Plotting the arc of Movement Page 12 3.5 Spacing the Motion Page 13 3.6 Inbetweens Page 14 3.7 Camera Page 15 3.8 Editing Page 16 4. Practical Aspects 4.1 The Light box Page 17 4.2 Top Pegs and Bottom Pegs Page 18 4.3 Animating in Blue Pencil Page 18 2 5. The Animation Technique 5.1 Ways to Animate Page 19 5.2 Single Frames and Double Frames Page 20 5.3 Timing Problems Page 20 5.4 Overcrowded Animation Page 21 5.5 Anticipation Page 22 5.6 The Take Page 23 5.7 Overlapping Animation Page 25 5.8 Animating the Character Page 26 5.9 Tracebacks Page 27 5.10 Animating the Letter Page 28 5.11 Water Animation Page 29 5.12 Bubble Animation Page 30 5.13 The use of Stills Page 30 5.14 Line Flickering Page 30 5.15 Quality of the Line Page 31 6. Conclusion 6.1 Regrets Page 32 6.2 The question – 2D vs. 3D? Page 32 6.3 Conclusion Page 33 7. References Page 34 8. Acknowledgements Page 37 9. Appendix – Dope Sheets Page 38 3 1. Introduction to the Project 1.1 Aim To animate a short sequence from the second year character design storyboard, conveying both character traits and narrative, using the 2D hand drawn technique. 1.2 Product A 20-30 second, hand drawn animation conveying a short section of a story. No colour. Approximately 150 hand drawn frames. 1.3 Introduction Animation is the means of creating magic on paper. The famous animator Richard Williams, refers to the ‘aphrodisiac’ qualities of creating images that ‘walk and talk and think’ (2001, p.11). My own passion lies in creating stories, particularly those which come alive through animation. The project focussed on learning another aspect of animation. Hand-drawn animation. The reason for settling on this idea was primarily because it was an incredibly exciting topic. Secondary considerations indicated that the project would be of huge benefit to the development of animation skills and would lead to a reexamination of one’s method. The rest of this chapter introduces the project, explaining the history behind the idea and detailing why it should qualify as an innovation. Chapter 2 comprises of research to identify the stages of the 2D process within the industry pipeline. This information provides the basis for formulating a personal method of working, which is explored extensively in Chapter 3. Chapter 4 clarifies a few practical problems with regards to having to work with new unfamiliar equipment. Chapter 5 focuses on actual animation technique, involving detailed research and extensive assessment of problems, successes and failures. The project is concluded in Chapter 6. 1.4 The Project as an Innovation The fundamental question that is repeatedly asked is ‘how do you animate?’ The course sadly does not offer lectures on animation techniques and one may 4 presume that many CG students simply sit down at a computer and work away haphazardly until they have something that looks reasonable. By comparison the traditional 2D animation students study the practise in fine detail. Once they have mastered the art of hand drawn animation, they might switch to CG animation, simply transferring all their acquired knowledge. It is precisely the difference between the disciplines that places hand drawn animators at such an advantage. Computer animation can support a haphazard and unstructured approach, though it will not always lead to great results but the sheer time consuming nature of hand drawn animation dictates that it must adhere to a tried and tested regime. In short, one needs to experience 2D hand drawn animation in order to establish a method of working and to better understand the principles before embarking on a career in 3D animation. This was an innovative project for me as I had never before attempted 2D animation. I had to greatly alter my working method and technique in order to successfully negotiate the numerous problems that arose from this new discipline. Such problems included mastering the artistic technique, which comprised of learning how to calculate the timing, drawing the keys and betweens and following the numerous golden rules on anticipation, squash and stretch, whilst exploring the various practical applications such as using a light box and compiling the animation. 1.5 Choosing the piece The original intention was to produce a series of unrelated animation sequences showing Flambio in various types of actions as befitting to his character and era, for example a sequence showing him daintily hailing a stage coach with his handkerchief or admiring a new outfit in the mirror. However on closer inspection the second year animatic revealed a few short scenes, which would be entirely suitable for a twenty second animation, plus there was the additional challenge of trying to convey a story which required an emotional development of some kind. The two sequences that were shortlisted depicted Flambio trying to decide what to wear and Flambio in his bathtub, reading his mail. Both were nicely contained sequences and choosing between them was hard. Tutor Claudia Moore and friends agreed on the bath scene as they liked the image of the bath and thought it a nice setting for a story. In addition it comprised of slightly simpler animation and with 5 hindsight this was a very wise decision. The time limit really restricted the amount of secondary animation that could be undertaken and there would have been an enormous amount of cloth movement to animate in the dressing sequence. 1.6 Background to the Character The Fop, immortalised in the Restoration Comedies of Charles II’s era, was an extreme symbol for an age obsessed with decoration and style. He embodied the flamboyant and frivolous taste in its most exaggerated form and exuded continental influence. Sir Flambio Foplin is the most outrageous fop living in Charles II’s London. His love of shoes and all things fancy, is matched by his absolute disregard for money and all things necessary and mundane. 1.7 Synopsis Sir Flambio Foplin is taking his morning bath and casually perusing the post. He tosses away many letters, no doubt bills, with bored irritation but then stumbles across a very unwelcome and threatening letter from one of his more dubious creditors, Jake the Rake. The letter orders Flambio to repay his outstanding debts or cross swords at dawn. Now Flambio can definitely tell his Moroccan silk from his Venetian lace but his swordsman skills are sadly lacking and there is no doubt as to the outcome if Flambio and Jack cross steel. Flambio leaps from his bathtub in a state of sheer terror sending soapsuds flying everywhere. 1.8 The difference between 3D and 2D animation. The obvious difference between CG animation and hand drawn animation is that the former produces immediate results. One can quickly manipulate the character into two key poses, guess the timing between them and playback to assess whether this timing works. Nine times out of ten it needs adjustment. In this respect CG is a medium where one can create animation through trial and error, often spending days playing a section over and over again, tweaking the timing. Hand drawn animation does not afford this luxury. It is time consuming and the results are not immediate. Each drawing involves a considerable amount of work, even in its roughest state and even more importantly, the artist can only see if the 6 animation is successful after he or she has completed a chain of such drawings. In short, the hand drawn animator cannot afford to create keys that do not work and animation where the timing is incorrect. It is not a medium which is open to trial and error. It needs to be accurate first time. 7 2. The Industry Pipeline One could not possibly create a method of working without researching and compiling of a simple pipeline of steps in accordance with those deployed in the film industry. Hanna-Barbera’s (Butterworth & da Silva, 1979, p.125) depiction of the pipeline as seen in Figure 1, can be simplified into the following stages: Storyboard A ‘visual highlight of a script’ with enough information to convey the story to the viewer (Butterworth & da Silva, 1979, p.36) Animatic Conveys more information than the storyboard - particular attention to timing. Bar sheet – information on timing for scenes and camera movements Exposure Chart/ Dope Sheet Information from the Bar sheet is transferred to the Exposure Chart or Dope Sheet. It is as Raul da Silva describes a ‘visual display of action to be filmed. It shows field sizes, character movements, pans and every movement for the animation sequence. It is used by the key animator & ultimately created for the cameraman as a blue print. It accounts for every single frame in the picture’ (1979, p.116). The Path of Action Raul da Silva summarises this task: This step is used in setting up extremes for character to be used by the key animator…It conveys different information to the storyboard as it gives you an idea of the action required in the sequence of motion & shows the most extreme character poses in the sequence (1979, p.37). Background Key animator 8 Plots the key poses, then the extremes and finally the breakdown position. Inbetweener Draws the specified number of inbetweens at the specified spacing. Flipping Technique used to check the smoothness of motion. Cleanup Tracing process – reducing every drawing to single tidy line. Inking & Opaqueing Outlining and painting colours. Gloves are worn to prevent fingerprints marking the acetate. The outline is often done on an electrostat. Colours are painted on the rear of the acetate. The checker Checks for mistakes comprising of broken lines, dirt and painting mistakes. Camera man Uses exposure sheet Editing Compilation of animation Figure 1: The stages of production by Hanna-Barbera (Butterworth & da Silva, 1979, p.125) 9 3. The Method Having identified the stages of the 2D process within the industry Pipeline, it was time to use this information as the basis for formulating a method of working. It was the aim to produce a pencil sketch animation, so the pipeline did not include the cleanup stage or the inking and colouring stage. The storyboard and animatic had already been created and assessed, so the first task became the problem of timing. 3.1 Calculating the Timing Calculation of timing was the first stage in the animation of a scene. It was a source of some confusion and anxiety. How could one know how many frames to place between key poses? The exact timing was vital for the correct composition and number of inbetweens. Two solutions were explored with varying degrees of success. 1st Solution The first solution was tested on a very short simple section of animation, which was a trial and did not feature in the final project. The animation was of Flambio holding an outfit up against himself and deliberating on whether to wear it. Two keys were drawn, the start and end frame of the animation, the former depicting him holding the outfit loosely, the latter where he had pulled it up under his chin. From these keys an inbetween was calculated and all three drawings were brought into Adobe Premier Pro to work out the timings. Trial and error established that the drawings worked on double spacing but since the movement was so quick it required two further inbetweens each side of the breakdown, in order for the sequence to run smoothly. This approach seemed quite easy but there were obvious disadvantages. It meant that after every couple of drawing the outcome would have to be accessed in Premier Pro and one would never know how many frames were required for a given movement until the animation was finished. This would make planning overlapping animation and easing in and out of movements incredibly tricky. In short, there would be no ‘blueprint’ to work from and one would be effectively improvising. Instead it became obvious that a dope sheet was required, with all movements for every bodypart accounted for, down to the very last frame. 2nd Solution 10 The second solution was to video a subject acting out the animation. This was also fraught with problems as a person could not satisfactorily impersonate a cartoon character and there was a danger that his or her rhythm would permeate Flambio’s actions. However there was not a viable alternative. After filming the action, the movie was played in Premier frame by frame and one could begin to draw up a dope sheet of movements. A huge amount of information was recorded, for example the number of frames it took for the character’s hand to travel from A to B, when blinking occurred, the direction in which the subject was looking and when the direction changed. The result was an in-depth guide for the scene, which was rigidly adhered to. 3.2 Dope sheet The dope sheet was a new experience. Having avoided using one in CG animation, it suddenly became essential in the creation and planning of hand-drawn animation. It organised the timings for actions into a clear, easily accessibly and visual layout. The benefits were that one had a chart detailing everything that was required in order to successfully animate. One could see where one was going and could plan time accordingly. Since the industry dope sheet accounted for many things that were irrelevant to the Flambio animation, it seemed sensible to use a custom made dope sheet, on which more information could be stored on the timing of the action. Since the pace of Flambio exceeded that of a human, an initial rough dope sheet recorded the timings from the video, which were carefully considered in the formation of a second dope sheet, drawn up to store the timings used in the actual animation. The most detailed dope sheet was made of the opening scene where Flambio discards his mail and in the writer’s opinion the scene benefited enormously from this approach. It stands in stark comparison to the last scene, which was made without a video or a dope sheet and fails abysmally. See Appendix for dope sheets. 3.3 Key Poses The next stage became to identify the key poses and draw them. The key drawings convey the story. It is vital that these drawings work. Richard Williams recalls an incident where he was watching Frank Thomas spend 11 ages drawing a cat, then he realised that the drawing was Frank’s key (2000, p.60). Similarly, the key drawings in the Flambio project, were also the most time consuming. Often huge scraps of waste paper were churned out before a suitable drawing was produced. The main reason for discarding a drawing was that it didn’t have enough impact. Exaggeration became the watchword. However exaggeration involved taking a leap of faith and drawing something that seemed outrageous to the rational mind. This accounted for all the waste. With hindsight all the keys could do with exaggeration by another 100%, particularly those in the two takes. 3.4 Plotting the arc of Movement. Having completed all the keys, the next task became to take two consecutive keys and plot a path of motion between them. Tony White offers would-be animators the following fundamental piece of advice: Remember that everything that moves in life moves in arcs (1986, p.38). In Figure 2 he demonstrates how even a turn head incorporates a slight downward movement, to prevent the features from appearing to slide across the face. Figure2: Correctly animated head turn incorporating an arc (1986, p.38). Richard Williams offers similar advice recounting how one day an animator was having trouble animating a horse. When he joined up the eyes, the problem became clear. The horse should have been moving in smooth arcs (Figure 3). 12 Figure 3. The motion path of the horse. The correct path of the horse moves in arcs (2000, p.90) It was therefore necessary to ensure that all Flambio's movements travelled in arcs. This actually became a fundamental part of the animating process. After plotting the two key poses, the next task was to create a rough arc of movement running between the two keys. This was plotted on a separate sheet of paper before any of the spacing had been worked out and then acted as a guideline. The spacing was then worked out along the arc. Figures 4 and 5, show arcs that were created to describe the motion of the hands and the leap from the bath. Figure4 Figure 5 The arc of movement was plotted to describe the intended motion of the hands and body. 3.5 Spacing the motion Once the arc of movement was completed it became necessary to work out the spacing and number of inbetweens and plot these at points along the arc. The arc and the spacings formed a template for the subsequent drawings and although the template was on a separate sheet of paper, the method loosely resembled a much older way of animating which Richard Williams (2000, p.46) describes seeing in the work of Grim 13 Natwick. Figure 6 demonstrates Grim’s work. He not only draws the arc of movement but also plots in the spacing. Figure 7 shows the arc for Flambio’s hand movement and the spacing. Figure6: The work of Grim Natwick showing Figure 7: A drawing from the spacing worked out along the arc of motion Flambio animation showing (Williams, 2000, p.46) spacing worked out along the arc of motion. The biggest mistake made during the early part of this project, was to divide all the spacing up equally. If one returns to Figure 6, one can see that Grim slows in and out at each extreme. The tighter the spacing, the more cushioned the movement and the loser the spacing the more speed and/or impact the movement will have. The opening scene in Sir Flambio Foplin, is marred by the fact that everything seems to flow at the same speed. However the lesson was learnt. By the time I came to the ‘takes’, I was planning for impact, slowing out and hitting the overshoot with more force, though this could have been greatly intensified. 3.6 Inbetween Grim Natwick declared ‘bad inbetweens will kill the finest animation’ (cited Williams, 2000, p.52). The majority of the work and time in this project was spent on the inbetweens. It was a very difficult skill to learn. The inbetweens had to progress by just the right amount and often it was hard dividing the movement into the respective number of steps. Even when the spacing had been religiously plotted, the task was still a difficult one. Th e greatest personal hurdle was learning to draw the character from slightly altering angles; to envisage Flambio in 3D. Where possible the solution was to retrace the previous key but reposition this according to the spacing chart. This helped greatly and also had the added advantage of guarding against over- 14 animation. It was one of the hardest skills I had to master and has brought into sharp relief my abilities as an animator. However the animation seemed to flow reasonable well without any obvious staccato effects. 3.7 Camera Figure 8 shows the proper equipment used in the filming of animation. Figure 8: Animation Stand and Camera (Butterworth & da Silva, 1979, p.57) Raul da Silva explains that one can also use a normal camera on a tripod but this is infinitely more stable and professional (Butterworth & da Silva, 1979, p.55). With regards to the Flambio project, the choice lay between a camera on a tripod or a scanner. Both had advantages and disadvantages. The scanner was bound to produce images of better quality since it was so much closer and of a higher resolution, however the camera would be less likely to reveal pencil smudges accumulated over time. However both might be susceptible to slight movement. The choice was made to use the scanner since constant quick testing had resulted in much use of this piece of equipment. However the result of scanning a larger sized piece of paper resulted in images that were slightly off centre, creating a lot of problems when one came to edit the shots. The most obvious casualties are the close-ups. These could also have benefited from appearing slightly larger on the screen. 15 3.8 Editing Once scanned the images were imported into Premier Pro and the animation compiled. Most of the images had to have the background added in and while this was a relatively simple operation, the result was not entirely satisfactory. A small section of the bath, the rim, was present in all the animated images. It would have been a much better idea to have used the rim from the background image, since the animated rim moved manically due to scanning inconsistencies, with the result that the top of the bath shimmered and wobbled. This mistake was remedied in the worst cases, particularly the shots at the end of the film after the characters departure, as the lack of action rendered the wobbling painfully obvious. The scanner chose the most inappropriate time to start mal-functioning with the result that images continually came out discoloured and had to be rescued with layers copied from previous drawings. 16 4. Practical Aspects 4.1 The Light box The light box was to become an indispensable piece of equipment and with hindsight I would never attempt an animation without it, however I was used to curling up in a corner with a sketchbook on my lap and on first encounter, the formality of sitting at the light box filled me with dread. The vertical orientation of the board was totally at odds with my normal comfortable drawing position. Paradoxically the initial attempts to animate without the light box, only served to highlight the reasons for using one. The initial piece of animation was just a means of testing the water and not part of the project. It consisted of Flambio holding a gown in front of him and pulling it up under his chin, as mentioned previously. The animation was incredibly simple, consisting of three frames; two keys. The three drawings can be seen in Figure 9. The character did not move his feet and in order for him to appear in exactly the same position, it was necessary to animate the next key in exactly the same position on the paper. This necessitated the use of tracing paper so that a second drawing could be made while the previous drawing could be clearly seen underneath. In actual fact I had blundered upon the correct method of animating except that using the light box would have made it ten times easier. Many problems arose from the tracing paper moving about and parts of the previous drawing not showing through clearly. The result was reasonable but there was obvious movement where there wasn’t supposed to be. The light box was the practical solution. As Tony White explains, ‘most animation work is concerned with slight changes of movement from drawing to drawing. It is therefore necessary to see 2 or more drawings in relation to each other at the same time’ (1986, p.20). The light ensured that one could view four of five images simultaneously which was a major asset to the animation and the pegs prevented the paper moving about. 17 Figure 9: These three frames comprised a preliminary test made without the light box. It only served to highlight the impracticalities of not using one. 4.2 Top and Bottom Pegs The light box, had a peg bar at the top and the bottom, providing the option of attaching paper at either end. Although it was not a huge problem it seemed sensible to seek from reference books as to which method of working was considered most helpful. Richard Williams recounted numerous anecdotes and arguments between animators, while advocating that one made a decision based on personal preference. Tony White had more practical advice: There is no correct position and all animators have their own preferences. In my opinion it is better to have top pegs, because bottom pegs tend to get in the way of the animators hand while drawing. The only time I would use bottom pegs is when the animation is near the top of the screen so top pegs would tend to be a handicap while drawing (1986, p.19). As the light box was in an up right position gravity and comfort dictated that the top pegs were used. 4.3 Animating in Blue pencil One of the techniques that had been suggested was using a blue pencil for roughly plotting in shapes, since the blue wouldn’t show up under the camera. This was a recognised procedure in the industry. However this idea was rejected, firstly because it would have shown up under the scanner and secondly because of personal preference. 18 5. Animation Techniques 5.1 Ways to Animate There are three methods for creating animation as outlined by Richard Williams in his book ‘The Animators Survival Kit’ (2000, p.63). Each method has advantages and disadvantages. Straight Ahead. This begins with the fist key pose and moves progressively through the scene. The advantages are that it lends itself to ‘improvisation, vitality, creativity and spontaneity’(2000, p.63). The disadvantage is the animation might meander and miss the point and there is general disorganisation with regards to time planning. Pose to Pose This process involves initially drawing all the keys, then plotting the extremes, the breakdown position and finally the inbetweens. This method is more disciplined. One moves from Key A to B to C and seldom wanders from the path. It may lack the spontaneity of the first method but it does not risk rambling animation that evolves into a long drawn out trek around the world. However as Richard Williams explains the animation may end up ‘choppy or rubbery’(2000, p.63). Combination This is the recommended approach. One should create the keys first and then use them as a guide, while one fills in the animation using the straight-ahead method. Obviously there is no right or wrong method, it is entirely down to personal preference and situation. The writer has always animated using the first method, since the animation gains a spontaneity and life, but while the immediacy of CG can support such an approach, a much more disciplined structure is needed when approaching hand drawn animation to avoid costly errors. Considering the two factors of limited experience and the time limit imposed on the project, the decision was made to adopt the Pose to Pose method as it gave one absolute control over the animation and allowed one to plan accordingly. 19 5.2 Single frames and double frames. This is a subject of some contention between animators. Richard Williams recalls how ‘a lot of great animators say that twos are really better than ones, that ones lead to a mushy result, that broad fast actions on twos sparkle and adding ones diminishes the vitality’ however it his own belief that ‘if you plan for ones the result is usually superior to twos’(2000, p.79). The general consensus appears to be that most things can be animated competently on twos but faster action requires ones. Williams concludes that the best method to use is ‘a combination of twos and ones. Normal action on twos, fast or very smooth actions on ones’ (2000, p.79). This was the method deployed in the Flambio animation. Time necessitated economical working so normal action was animated on twos while the leap and the fast takes were animated on ones. 5.3 Timing Problems Richard Williams confidently asserts that the major beginners mistake is ‘Doing too much action in too short a space of time’ (2000, p.99). Flambio Foplin shows many instances of this mistake. In fact most of the flaws in the animation, stem from trying to cut corners and guess the timing. With hindsight I realise that I was misled by the sheer volume of work into thinking I had animated much more than I had. Therefore any animation that wasn’t carefully timed, generally wizzed by. The first instance of this error was in the animation of the bubbles. The idea was for the bubbles to spiral upwards but in reality they shot around like little rockets. Fortunately this problem wasn’t hard to correct. The bubbles were erased and re-positioned in much closer proximity to the bubble in the preceding frame. Flambio’s facial features in the opening scene have also caused some concern. They are simply too busy, though poor tracing may have contributed. The animation of the splash in the final scene where Flambio leaps from his bath, afforded the same problem but this will be dealt with in the water section. In complete contrast, the leap motion was far too slow. Again the timing had not been measured and the mistake was to underestimate how fast the character should move. 20 There was no feeling of acceleration or weight and the character appeared to drift airily off screen. The solution was to take out some of the keys but the result was still bland, leading one to suspect that there was more at fault here than just the timing. It was a difficult scene and one that was reanimated several times. The first attempt was marred by over animation. There were two keys, an initial key depicting Flambio in mid-leap and a second key depicting him extending forwards but the timing was too fast for such a drastic transition Figure 10. The decision was made to remove the second key and retrace Flambio in various positions moving across the paper. This produced the opposite extreme, too little animation. However this was never corrected. Figure 10: The two keys initially used in the Leap sequence. 5.4 Overcrowded animation In certain scenes there was simply too much animation. Why was this so? As with the timing problem, the sheer volume of work was very misleading and as one worked through pages where a single hand moved a fraction across the page, the understandable reaction was to mistakenly believe that the scene needed a lot more happening or else the audience would die of boredom. In reality the hand flashes across the screen and so do all the other bits and bobs, with the result that the poor viewer does not know where to look. The opening scene where Flambio discards his letters, was the first to be animated and shows the greatest evidence of this flaw. Tutor Claudia Moore has advised that I should have waited for the letter to almost settle before bringing the toe into the scene, as a result there are two many strands of action all happening simultaneously. Bubbles, letter, character, facial expression, toe. Poor 21 viewer! It was a good lesson to learn. Richard Williams advises ‘Do one thing at a time and be crystal clear’(2000, p.316) and this was reinforced by many of the animations that were viewed. ‘Geraldine’ (2000), makes particular use of still images. In a scene with two or more characters, it is not uncommon for only one character to be moving at any one time and generally the movement is restricted to one small area of interest e.g. the mouth. In ‘Intolerance’ (2000), there is a similar focus on the mouth, which is accompanied by occasionally blinking eyes and in ‘Father and Daughter’ (2000), the movement is again quite minimal. The feet are animated peddling the bicycle but there is very little animation in the body or the clothes. In short, movement attracts attention and as the films all show, it can be a very good tool with which to manipulate the viewers’ attention. This lesson was learnt the hard way. 5.5 Anticipation Cartoons tell a story and therefore ‘every move, manner & gesture (has to be) crystal clear’ (Butterworth & da Silva, 1979, p.33) in order to convey the narrative to the viewer. Therefore it is very important for the animator to direct attention towards the right area of the screen so that valuable information is not missed. This is done via anticipation, which is possibly the most essential component of animation. John Halas writes: One of the tricks, which an animator has to learn, is how to attract the attention of the audience to the right part of the screen at the right moment. This is of great importance to prevent the audience missing some vital action and so the thread of the story. If there are a number of static objects on the screen with attention divided equally among them and suddenly one of the objects moves, all eyes go to the moving object about 1/5 second later. Movement is in effect a signal to attract attention. If therefore a preliminary movement is made before the main movement, such as drawing back the foot before a kick, the attention of the audience can be attracted to the foot. This ensures that they will see the kick when it comes. (Halas & Whitiker, 1981, p.58) Almost every movement has anticipation and the anticipation is always in the opposite direction to the subsequent action. If someone looks up, they look down first. Thus when Flambio is startled on discovering the letter he leans backwards before flinging himself forwards and on reading the contents of the letter, he momentarily 22 leans forward before going back. With hindsight I cannot imagine animating without anticipation but prior to this project I had very limited experience of this technique and certainly would not have imagined that so many actions warranted such treatment. It was a particular aim of this project to develop this skill, hence I took the opportunity to animate two separate ‘takes’ as discussed in the following section. 5.6 The Take Tony White describes the take as ‘one of the most powerful ways to register surprise in a character’. It is an ‘exaggerated reaction to an event ‘ (1986, p.106) Figure 11 depicts the various stages involved in the take. The process starts in the normal position before shrinking to a preparatory gesture, the Squash. From here it moves into the overshoot gesture, or Stretch, before settling back at the normal position. Figure 11: The stages involved in the Take (Halas & Whitiker, 1981, p.76). A take usually lasts about 14-16 frames and follows quite rigid timing. Whitiker places the squash on frame 5 and the stretch on 9. Richard Williams (2000, p. 286) also positions his squash on 5 but his stretch occurs on 8, before coming to rest on 16, as demonstrated by Figure 12. In most of his examples he animates the slower anticipation on twos and the fast action on ones. 23 Figure 12: Richard Williams’ example of a take (2000, p. 286) The amount of squash and stretch one uses depends on the nature of the character. Williams explains that when dealing with a ‘flesh and bone anatomical character there should be little visible squash & stretch otherwise the character will look rubber and unreal.’ (2000, p. 109). In animating Flambio it seemed appropriate to use some squash and stretch since the character was comparatively cartoonish. Flambio’s reaction to the letter provided the action for the first take. In this instance animation occurred before an in-depth study had been made on the topic and as a result, the work differed in numerous ways from the examples of Whitiker and Williams. Figure 13 highlights the stages of this take. From the normal position, Flambio leans back in a stretch and then flips forward abruptly back into the normal position. Quite by chance I had stumbled upon Williams timing, using twos to animate the slow anticipation and ones to catapult Flambio forward. For a first attempt it was competent. There was a small amount of stretch in Flambio’s arms at the extreme, however the animation could have benefited from a squash at the beginning, which was something I set out to remedy in the subsequent attempt. Figure 13: The stages of the first take . 24 Flambio’s reaction to the contents of the letter initiates the second take. It was a closer shot and therefore provided the additional challenge of animating the facial features. These were to form part of the squash and stretch as demonstrated by the work of Williams and Whitiker. Figure 14 demonstrates the stages of this take. From his normal position, Flambio shrinks closer to the paper and his expression condenses slightly, he then springs upwards into the overshoot gesture; neck and shoulders stretched and expression elongated before returning to the normal position. The timing again followed Williams’s example with the anticipation occurring on twos, the action on ones before coming to rest again on twos. It was far from perfect but showed signs of progress. With hindsight the squash could have been much more dramatic. Figure 14: the stages of the second take. 5.7 Overlapping animation. Overlapping animation describes the process whereby different parts of the body come to a halt at different times owing to the transmission of force through the various joints in the body. The extremities, the hands and feet, are often the last to start moving as forces are filtered first through the shoulders or hips and then through the elbows or knees. The same technique applies to hair, clothing and regions of excess body fat. The animation suffered because there was not a detailed exploration of this technique. The tendency in the opening scene was for the hands and head to all move in unison, despite the video research clearly showing the head leading. This was sloppy animation. However the head stops before the hand reaches the backward extreme and the hand begins moving forwards before the head comes up. In addition the hand lags behind the movement of the arm as shown from the sequence of drawings in Figure 15.. 25 Figure 15: The images show the arm swinging forwards and the hand trailing. 5.8 Animating the character Character animation is the ultimate achievement of animation art. Characterisation in animation is concerned not so much with what the characters do, as how they do it. (Halas & Whitiker, 1981, p.118) It is reassuring to discover that even professional animators shy away from character animation. Richard Williams recounts how: Frank Thomas, master of animating empathy and pathos always criticised me for spending too much time on spectacular surrounding animation and not enough of going straight for the emotional centre. Part of the reason was that we weren’t good enough at it so we’d work on the ‘world of the piece’ and leave the ‘Hamlet’ stuff till last – but franks criticism is valid (2000, p.317). In order to convey the character of Flambio, it was necessary to consider what made him unique. Tony White lists these elements as ‘size, weight, personality, speed, psychology and physical well-being’ (1986, p.57). Flambio is slight, light and bendy like a little reed. His body language is dainty and befitting of his era. In terms of Laban, Flambio’s movements could be described as a mixture of flicking and gliding. He is quick, excitable, prim and snooty yet easily startled. This latter quality was conveyed by the use of two ‘takes’, which had the added advantage of allowing repeated practise at this particular technique and was further reinforced through the rapid animation of him falling over backwards in shock, a peculiar mix of chaotic daintiness. In the opening scene where he discards his mail, a lot of attention was given to elegant hand gestures with slight flourishes and the dainty descension of the letter was intended to mirror Flambio’s physicality. This was combined with aloof positioning of the head and a dainty toe wiggle to suggest his thorough enjoyment of the mornings pampering session. Attempts were 26 made to keep the action light and swift and upbeat. In comparison to a heavier object, Flambio was not so restricted by gravity. He could make sudden fast movements and come to rest abruptly. The characterisation could have been a lot clearer and stronger and would have benefited from exaggerating the ‘takes’ even more, however it does go someway to conveying the impression of a dainty, rather posh little chap who is rather inept at dealing with stressful situations. 5.9 Tracebacks Tony White draws attention to the irritating problem of seeing ‘parts of the animation suddenly freeze, while other parts of the scene are freely animated’. He attributes this freezing to the fact that ‘a held drawing is used’ and his solution is that instead of placing the static portions of the drawing on a held cel, it should be retraced. He explains that ‘when filmed the tracebacks have life, which the held drawing does not’ (1986, p.38). The Flambio animation created a similar problem. In the interests of time and practicality the background, Flambio’s bath, was edited in afterwards. However using one frame for the entire sequence resulted in severe discrepancies. The rest of the scene flickered with a sketchy quality while the background appeared frozen. There was a similar problem in the sequence disclosing the contents of the letter. Since it was important for the viewer to be able to read the letter, it seemed wise to refrain from tracing the message in to every drawing, in case the letters should flicker and compromise the legibility. However the result of editing the letter in afterwards was that it remained peculiarly frozen on a flickering sheet of paper, whose movement distracted the viewer anyway. It was decided to trace the message in to every drawing to see if Tony White was right. It worked much better. The letters remained legible but had a life of their own. The majority of the sequences of animation had a small static section at the beginning and end, like bookends, so that the action would not be to quick for the human brain. As far as time permitted, these stills were retraced. The result was far improved in comparison to the ‘bookends’ that were left as static holds. 27 5.10 Animating the Letter Experimentation was required to see how a letter dropped. The conclusion was that letters are actually quite heavy and fall abruptly, while a single sheet of paper drifts slowly and randomly to the floor. Regardless of weight, both objects rotated in the air, as Halas explains: Most objects have a tendency to rotate when flying through the air, the object is then drawn pivoting by a fixed amount about the successive positions of the centre of gravity along the parabola’ (1981, p.38). However what was particularly interesting about the fall of the single sheet was that occasionally an up current of air would lift it higher for a moment and as a result it seemed to fall in stages, each swoop getting lower to the ground. This proved far more interesting to watch, more of a challenge to animate and more importantly it echoed the dainty characteristics of Flambio and his surroundings. However, it was decided that the letter should fall in neat symmetrical swoops as this would not unduly distract the viewer from the main action and this same principle was applied to the bubbles, which twirl upwards in neat symmetrical curves. The process of animating both the bubbles and letter was greatly aided by creating a set of motion paths on a separate sheet of paper, which could the act as a guide. Figure 16 shows the motion paths of bubbles and the falling letter. Figure 16: Plotted motion paths for the bubbles (brown, red, blue and black) and the letters (green) 28 5.11 Water Animation Water animation was a new and scary prospect. It had the potential to go very wrong and ruin the entire scene. Halas explains that in achieving ‘realistic liquidity’ the ‘timing for animation of water is quite critical… If timed too slowly it looks oily or even treacly, whilst if timed too quickly it may fizz in an unliquid way (1981, p.89). The animation of the water would have proved extremely time consuming especially if one had to create waves and ripples every time Flambio moved in the bath and this dilemma was cunningly avoided by topping the bath with a hefty wad of bubbles and suds. However the splash resulting from Flambio’s sudden leap from the tub, could not be avoided. The first task was to study how water behaved in some detail. As water moves too fast for the eye, a few splashes were filmed, which could then be viewed frame by frame. The result was in keeping with Halas’ depiction: It starts as a mass of water, which spreads out into irregular sheets, held together by surface tension. As it spreads out even further, the surface tension breaks down and the sheets disintegrate quite suddenly into drops, which continue outwards individually. Each little droplet making up the mass of the water proceeds on its own trajectory or parabola regardless of what happens to any other part of the splash(1981, p.89). Figure17shows two images from the animation demonstrating the two depictions of water above. Figure 17: The pictures demonstrate the technique I was using to animate the splash in accordance with Halas depiction. There is an initial wave of water, which breaks into droplets as the surface tension breaks down. The leap sequence was not successful and the water was possibly one of its redeeming features. A highlight was the animation of a few ripples in the empty tub at 29 the end as the water settles. However although the water did not resemble treacle it could have benefited from being much slower. Once again I was misled by the volume of work into thinking that I had animated more time than I actually had, with the result that my animation flashed by. This would be one of the most fundamental lessons that one could carry into any further experimentation within this field. 5.12 Bubble Animation It was suggested that the bubbles in the bathtub were looped to save time in animation. With hindsight the flaw in this idea should have been obvious. The result was that the bath water appeared to be heaving and the only solution was to return to the light box and animate every single frame with new motion. 5.13 The use of Stills Two sequences contained stills. The first sequence was opening the letter and the second was the panic scene. The second scene did resemble animation due to the speed with which it was edited but it merely a string of key poses. Extensive study of animations, particularly ‘Geraldine’ (2000), had enlightened me to the fact that stills can work best in creating the desired effect. The disjointed chaos of the panic scene was nicely conveyed by the succession of predominantly non-sequential images. 5.14 Line Flickering A lot of animators proceed beyond the simple animation of shapes and incorporate the animations of lines, colour and shadows. This technique is carefully deployed to create a certain sensation in keeping with the nature of the piece. In a ‘Girls Night Out’, the animation of the shadows beautifully captures the impression of the husband watching television in the dark, the light flickering as the image changes. In contrast the flickering in the pub scene, serves to suggest movement and bustle everywhere even when the characters are still. This same principle is explored in ‘Crac!’(1981), where the animation of colour creates a spectacular cacophony of chaos and fluidity during the barn dance and adds to the overall impression of the ever changing, ever merging nature of time. There was a great deal of line flickering in the Flambio animation owing to the lack of a clean up and the slight discrepancies in the scanning process. Although 30 initially mortified I came to like the result. It had a fresh sketchy quality and seemed so much more alive. More importantly, the setting for the scene was the bathroom and the evidence of steam would cause shapes to appear to shift. While the animation of shadows and colours would have created a stronger sensation of steam, the I am glad that I stumbled upon this problem as it has opened my eyes to different ways of animating and forced me to look outside the ‘Disney’ box. 5.15 Quality of the line The decision to animate in pencil created a great deal of problems and possibilities. Unlike the ink pen, a pencil granted greater versatility with regards to line quality. Lines could be very heavy and dark or very faint. The darker lines would attract the viewers’ attention, while the lighter lines would detract attention. In theory one could manipulate the viewers attention towards the areas one wished, similar to the use of a moving object interposed among static objects. This technique was deployed with varying degrees of success. The initial worry when viewing the opening scenes was that the constant fierce bubbling in the tub was distracting the viewer from the primary animation of the character. However it seemed a shame to dispense with the bubbles, as the idea of the tub resembling a C17th Jacuzzi was quite a jolly and upbeat image. The solution was to lighten the bubbles . The result was far less intrusive and the bubbles merged into the background. However the choice of medium created many problems and not all have been effectively eradicated due to lack of time. It has been impossible to work with a continuous pressure and some images are darker than others, ruining the continuity of the piece to a certain degree. Sometimes one particular feature has accidentally been made darker, with the result that on sporadic frames our attention is drawn to some random part of the scene. Again the result is disharmonious. Other images have been too light and almost disappeared off of the paper. These required lengthy retracing, since editing in Photoshop would have distinguished the image from its peers in appearance. 31 6. Conclusion 6.1 Regrets There were many sections within the piece that could not be animated owing to a lack of time. This particularly affected the secondary animation, which was not explored to its full potential. Ideally the curtain should move when Flambio leaps out of the bath and the letter in his hand should move when he ‘takes’ and flaps it about. It was never proposed but it would have been an interesting experience to undertake the cleanup and inking process, possibly using acetate so that some experience with colouring cels could be gained. The piece works fine in pencil and there are no regrets about using this medium but it would have been interesting to see how it looked when coloured in. The other regret was that one of the avenues of exploration had to be sacrificed, though not before careful consideration as to its relevance. In the brief it had been proposed that there would be experimentation with practical methods of producing the animation, using a scanner and digital camera. When I first approached the project everything was extremely mysterious and unfathomable but as I gained experience scanning and collating the animations, it became obvious that the whole process of using the digital camera would not qualify as an innovation any more. I knew how to implement the process and I knew what to expect from the outcome. Furthermore, the project was fundamentally about actually mastering the hand drawn technique and since time was running out I sought advice from my tutor Chris Sams as to whether this should be prioritised over the more redundant experimentation with the camera. He agreed. 6.2 The question - 2D vs. 3D? 2D is very much harder and more time consuming and if one doesn’t plan ones animation diligently, there is very little chance of anything working. With 3D, the results are immediate and one can effectively dispense with all the planning and still manage to produce something reasonable, though this method of working is not advisable. 32 However, with hindsight I realise that I prefer 2D animation. I have a long way to go and possibly will never have the opportunity to explore it again but the animation I produced felt so much more alive and subtle. With 3D, one puts a character in one pose and then in another pose and the transition is at the mercy of the computers calculations. With the 2D method I was able to exercise so much more control over the result. It was easier to convey the subtle aspects of personality and expression and taught me the benefits of careful timing, particularly in the ‘takes’. I wont be using the computer as a crutch any more. 6.3 Conclusion I was not expecting perfection. I was not expecting to produce a piece of finished and polished super animation. The project was always going to be work in progress, with areas that could be improved and added to. The fundamental aim, as outlined in the introduction, was to gain a deeper understanding of the animation techniques and rules, which I had hitherto remained oblivious to. Prior to this project I did not have a technique by which I animated and I was floundering haphazardly at the computer, sometimes producing animation that seemed to work through sheer luck and sometimes producing animation that looked absolutely dreadful. This project has forced me to understand and master some of the skills that will form the foundations for future animations. It was a learning curve. I struggled with a new technique and forced myself to animate according to a set of rules in an unfamiliar way. However it was also my aim to produce a piece, which did have elements that worked and could be exhibited as a piece with potential, demonstrating some successful applications of the things I had learnt. In this I feel I have been successful. 33 7. References BOOKS BUTTERWORTH S. & DA SILVA R., 1979. The World of Animation. New York: Eastman Kodak Company. CULHANE S., 1988. Animation: From Script to Screen. New York: St Martins Press. HALAS J. & WHTIKER H., 1981. Timing for Animation. London: Focal Press. WILLIAMS R., 2001. The Animators Survival Guide. London: Faber & Faber Ltd. WHITE T., 1986. The Animators Workbook. London: Phaidon Press Ltd. FILMS Annecy 2001 Awards, 2001. Video. France La Morve, 2001. ArnauldPoitevin, Pierre Santamaria, Eddie Mehong Shit Li, Claire Lee. Comics Trip, 2000. Christophe Barnouin, Natalie Bonnin, Luc Degarrdin. France: SUPINFOCOM Geraldine, 2000. Arthur de Pins. France: Arthur de Pins AP200, 2000. Loic Bail, Aurelien Delpoux, Sebastien Ebzant, Benjamin Lauwick. France: SUPINFOCOM 34 Hasta los Huesos, 2001. Renee Castillo. Mexico: Calavera Films Moya zhizn/Its my life, 2000. Natalie Berezovaya. Russia: Argus International. Intolerance, 2000. Phil Mulloy. Great Britain: Spectre Films Father and Daughter, 2000. Michael Dudok de Wit Pays-Bas. Great Britain: Cinete Filmproduktie/Cloudrunner Ltd. Annecy Awards 1990, 1990. Video. France Tango, Zbigniew Rybczynski Grand Prix Annecy 1981 Crac!, Frederic Back Special Jury Award Annecy 1981 Dimensions of Dialogue, Jan Svankmajer Grand Prix Annecy 1983 A Greek Tragedy, Nicole Van Goethem Grand Prix Annecy 1985 Ropedance, Raimund Krumme Special Jury Award Annecy 1987 Smatchkan sviat/ A Crushed World, Boyoko Kanev Grand Prix Annecy 1987 The Hill Farm, Mark Baker Grand Prix Annecy 1989 Animation on 4 Volume 1, Video. Connoisseur Video Next, 1989. Barry Purves. Feet of Song, 1980. Erica Russell. 35 The Victor, 1985. Derek Hayes, Phil Austen. Girls Night Out, Joe Destiny, 1980. David Anderson. Black Dog, 1987. Alison de Vern. 36 8. Acknowledgements Many thanks to: My tutor Claudia Moore for her unstinting support and inspiration., Chris Sams for his help and advice, Tim for his superb music composition My housemates and poor downtrodden boyfriend Sander. 37 9. Appendix 38