ab 5

advertisement

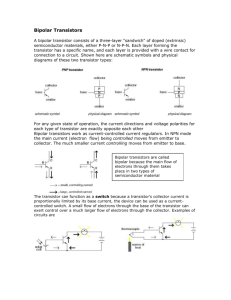

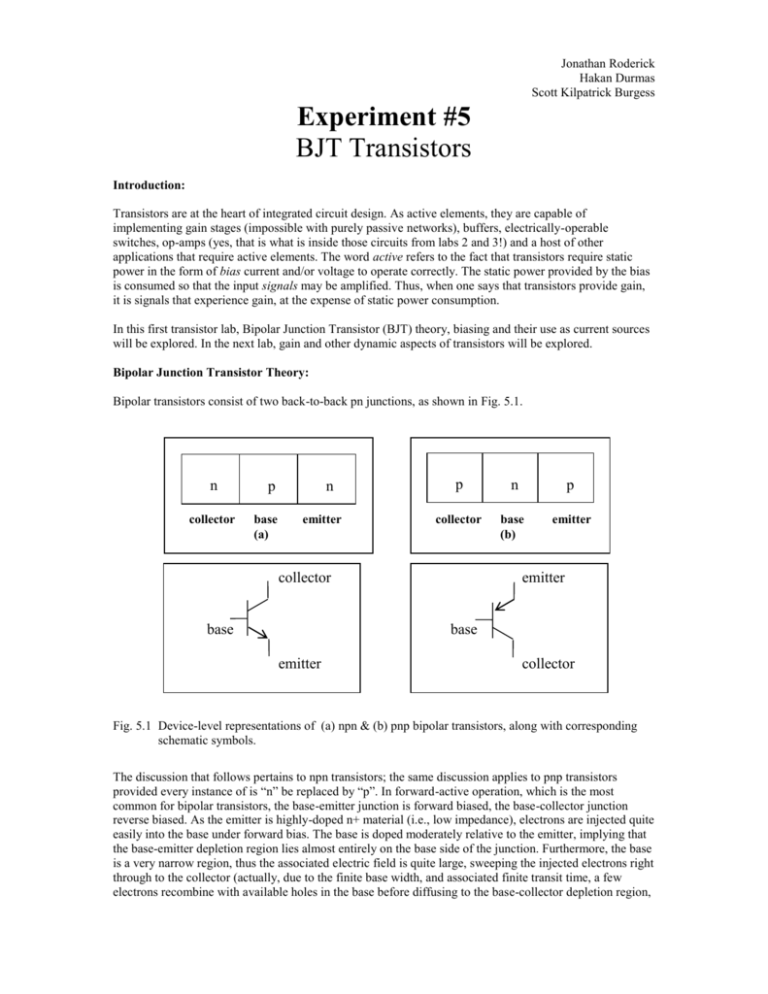

Jonathan Roderick Hakan Durmas Scott Kilpatrick Burgess Experiment #5 BJT Transistors Introduction: Transistors are at the heart of integrated circuit design. As active elements, they are capable of implementing gain stages (impossible with purely passive networks), buffers, electrically-operable switches, op-amps (yes, that is what is inside those circuits from labs 2 and 3!) and a host of other applications that require active elements. The word active refers to the fact that transistors require static power in the form of bias current and/or voltage to operate correctly. The static power provided by the bias is consumed so that the input signals may be amplified. Thus, when one says that transistors provide gain, it is signals that experience gain, at the expense of static power consumption. In this first transistor lab, Bipolar Junction Transistor (BJT) theory, biasing and their use as current sources will be explored. In the next lab, gain and other dynamic aspects of transistors will be explored. Bipolar Junction Transistor Theory: Bipolar transistors consist of two back-to-back pn junctions, as shown in Fig. 5.1. n collector p n base (a) emitter p n p collector base (b) emitter collector base emitter base emitter (a) collector (b) Fig. 5.1 Device-level representations of (a) npn & (b) pnp bipolar transistors, along with corresponding schematic symbols. The discussion that follows pertains to npn transistors; the same discussion applies to pnp transistors provided every instance of is “n” be replaced by “p”. In forward-active operation, which is the most common for bipolar transistors, the base-emitter junction is forward biased, the base-collector junction reverse biased. As the emitter is highly-doped n+ material (i.e., low impedance), electrons are injected quite easily into the base under forward bias. The base is doped moderately relative to the emitter, implying that the base-emitter depletion region lies almost entirely on the base side of the junction. Furthermore, the base is a very narrow region, thus the associated electric field is quite large, sweeping the injected electrons right through to the collector (actually, due to the finite base width, and associated finite transit time, a few electrons recombine with available holes in the base before diffusing to the base-collector depletion region, but this is not a dominant effect in modern processes). These electrons are the minority charge necessary to supply the reverse current through the reverse-biased base-collector junction. It is the forward bias across the base-emitter junction that supplies this charge, thus the current through the base-collector junction is not limited to the negligible reverse saturation current. In fact, neglecting recombination of the electrons in transit with available holes in the base, the current through the collector is practically identical to the current through the emitter. The really nice thing about the transistor becomes apparent if one explores what happens if the current injected into the collector is then allowed to flow into a resistive load, as shown in Fig. 2. Vcc Rload Vbe Fig. 2 NPN transistor with forward bias across base-emitter junction and resistive load attached between collector and power supply. As the base and power supply voltages are fixed, it follows that varying the load resistance causes a different collector node voltage to develop. Thus, the base-collector reverse bias changes. However, recall from the diode labs that the magnitude of the reverse bias voltage has very little effect on the reverse current (i.e., it approaches the reverse saturation current in the limit), and thus it is the electrons injected by the forward-biased base-emitter junction that control the collector current. The significance is that the transistor approximates an ideal controlled current source, where the controlling variable is the base current (which is in turn controlled by the base voltage, so you can think of that as the controlling variable if you prefer) and the controlled variable is the collector current. In comparison to the controlling variable, the load has relatively little effect on the transistor current! Now that the emitter and collector currents have been discussed in some detail, one must consider what base current (if any) exists before writing down the key bipolar transistor equations. First, recall that most of the emitter current flows through the collector, with some of the emitter electrons being lost to recombination with available holes in the base region. While this effect can be minimized by making a small base, there are always some holes in the base region, and these holes have to be supplied as base current. A second phenomenon is reverse current through the forward-biased base-emitter junction. Again, this effect can be minimized by heavily doping the emitter, but nonetheless, some reverse current exists, and must be supplied through the base contact. Now that the basic principles of bipolar transistors have been discussed, we can go ahead and write the three key equations for bipolar transistors, one relating collector current to the base-emitter voltage (i.e., the controlling variable), one accounting for the base current, and the third satisfying KCL: VVbe V I c I s e t 11 ce V a Ic p Ib t Ie Ic Ib (1) 1 Ic The second parenthesized quantity in the collector current equation accounts for the slight variation of collector current with collector voltage. Though ideally the collector current is influenced solely by the base-emitter voltage, the base-collector reverse bias does influence things a bit. Since the effect is not dominant, people usually model it with a simple linear dependence on collector voltage, with the slope determined by the Early voltage factor, named in honor of J. M. Early. This is a secondary effect, and for much of what is presented will be ignored. Biasing the common-emitter amplifier Consider the following common-emitter amplifier: Vcc Fig. 3 Rb1 Rc Rb2 Ree Common-emitter amplifier. The question is how to achieve the resistors such that a certain bias condition is achieved. The easiest way to see how to do this is with an example, so consider the following requirements: the base-emitter junction be forward-biased, the collector-base junction be reverse biased, the base voltage be approximately 1V and the transistor current be 1mA (assume the supply is 5V). Assuming the transistor beta is large (as it should be), one can assume for all design calculations that the collector and emitter currents are essentially equal. Since the forward-bias voltage of a p-n junction is somewhere around 700 mV, it follows that approximately 300 mV drops across Ree. Thus, for a 1 mA current, the emitter resistor should be approximately 300. We want to ensure that the base-collector junction is reverse-biased, so we choose (arbitrarily) a collector voltage of 3.5V. For a 3.5V output voltage, the voltage dropped across the collector resistor is 1.5V, which for a 1mA current implies a 1.5k resistor. Assuming that the base current is negligible, Rb1 and Rb2 form a voltage divider at the base, so to achieve a base voltage of 1V requires the resistors be in a 4:1 ratio. Resistors of 1k and 3.9k will work fine. Note that in biasing the transistor, the equations developed earlier were unnecessary; only the qualitative ideas of small base current and forward-bias voltages being around 700 mV were used. This may seem odd (after all, why did we develop the equations if we don’t use them?), but it is actually good practice to have as few circuit performance metrics as possible depend on transistor parameters, as these parameters vary wildly from one transistor to another. As an example, for a good transistor is large (say, 100 or better) but not at all predictable. One transistor might have a =83, while another has a =137. If your design was highly sensitive to , it would not have repeatable performance (i.e., if you built your circuit, measured it, and then replaced only the transistor, you would get different results). Thus, while the above equations are important, particularly for analysis and understanding basic transistor mechanisms, they are not always used in design. However, there are exceptions to every rule, which the next section demonstrates. A bipolar current mirror: When you build the common-emitter amplifier in the lab, you will probably notice that the measured current is not exactly 1mA; in fact, it may be off a great deal. The main reason for this is the rather arbitrary assumption of a base-emitter voltage of 700 mV. It is a simple matter then to adjust the emitter resistor to achieve the correct current. However, what if you had, say, 4 or 5 transistors, each requiring different bias currents? It would not be efficient to fine-tune each one by tweaking resistors; a better approach would be to fine-tune the current of one transistor, and then somehow force all of the other transistor currents to be a fixed multiple of this current. Thus, achieving the correct current in several transistors would rest on one the accuracy of only one current! Vcc R Iref Iout Q1 Q2 R1 R2 Fig. 4 Simple bipolar current mirror. Assume transistor Q1 has been biased appropriately to achieve exactly the right reference current. Applying KVL (and ignoring the Early voltage), one gets: I 1 R1 Vbe1 I 2 R 2 Vbe2 I I I 1 R1 Vt ln c1 I 2 R 2 Vt ln c 2 I s1 I s2 I 2 I1 R1 Vt I c1 I s 2 ln R 2 R 2 I c 2 I s1 (2) Beearing in mind that we want the current through Q2 to be a fixed multiple of that through Q1, largely independent of transistor parameters, it would be nice to make the logarithmic term (error term) disappear. If that happens, the currents through transistors are determined by simple resistor ratios! To make the error term vanish, the reverse saturation currents must have the same ratio as the collector currents. If the collector currents are to be given by a resistor ratio, the reverse saturation currents must be in the same ratio, which requires that the transistor areas be in the same ratio. This is routinely done in IC design, where ratios can be very accurate. However, using discrete components in the lab, the only way to make a transistor with bigger area is to parallel multiple transistors, which has the following drawbacks: 1) it takes a lot of space, 2) it limits you to integer multiples of the area of your reference transistor and 3) with discrete components, there is wide variation in the saturation current from one transistor to the next, so paralleling, say, 3 devices does not mean that the effective reverse saturation current is 3 times that of the reference transistor. However, note that the error term decreases inversely with R2; this means that using large reference resistors reduces the error term significantly. Secondly, note that the error incurred due to mismatched reverse saturation currents increases only logarithmically, so the error is not that substantial anyway. In the prelab, you will design a current mirror and investigate numerically the percentage error arising from the logarithmic term. Regulators again In previous labs, some simple regulators were explored. We return to this topic once more, now armed with some knowledge of transistors. Consider the circuit below: Vcc R Vcc + Vz _ Vout R2 Fig. 5 Voltage regulator employing BJT. This circuit is identical to one previously explored, except that now a BJT is inserted between the op-amp output and the output of the circuit. The idea is that realistically, op-amps can only source a few tens of milliamps of current, and this may not be enough for most applications. The BJT has the nice property that the emitter current is (+1) times the base current, so the op-amp can now get away with supplying a very tiny current to the base of the transistor, with the burden of driving the load resting on the transistor. An improvement to the above circuit, similar to what is used in actual power supplies, employs a technique called current limiting, as shown below: Vcc R Vcc + Vz Q1 _ Q2 Rf R2 Vout R1 Fig. 6 Voltage regulator with current-limiting capability. The idea here is that under normal operation, no current flows through Q 2, and thus the circuit operates identically to the previous voltage regulator. However, should the load start to source so much current that the voltage drop across Rf is enough to turn on Q2, then the collector of Q2 draws current from the op-amp, leaving less for the base of Q1, resulting in a lower voltage drop across Rf. Thus, Q1, Q2 and Rf form a negative feedback loop that tends to keep the output current at a desirable level. Thermal dependence of BJT’s Equation (1) indicates that the collector current of a BJT depends on the temperature of the device. In commercial circuits, lots of care is given to designing circuits that are independent of temperature. The resulting circuits can get quite complicated, but it is possible to explore the thermal dependence of BJT’s and make a (admittedly crude) thermometer without making life too unbearable. Consider rewriting (1) as follows: I Vbe Vt ln c Is (3) Looking at this equation, and recalling that Vt is proportional to temperature, one might deduce that V be is proportional to temperature. Experimental results indicate this is not the case; in fact, V be decreases with temperature. The key is the Is term. It turns out that Is has a temperature dependence as well, which experiments show fit the following equation reasonably well: I s Ioe Vg o Vt (4) Combing the above relationships with the empirical result that Io >> Ic gives: Vbe V go Vt ln I o ln I c (5) This correctly predicts that Vbe decreases with increasing temperature. Now, consider the following circuit: R Vd4 Vbat Fig. 7 Thermometer circuit. The BJT’s are hooked together as diodes (realize that by shorting the base-collectors terminals together, the result is a single p-n junction), and the battery and resistor set up a current for the diode string. If one has good SPICE models for the transistors, this circuit can be simulated over a range of temperatures, and from this data, Vgo and ln(Io) determined empirically. Again, though, this is more amenable to IC design, where the four transistors are well-matched (and, in case you are wondering, diodes in IC design are implemented most easily as diode-connected transistors). Using discrete components in the lab, there will likely be wide variation in the transistor parameters. In this case, one may use two different bias voltages at room temperature (use a standard mercury thermometer to determine room temperature), measure the resulting Vd4 and current, and thus extract an effective V go and ln(Io). After this initial calibration, one may heat the circuit with a heat gun and estimate how hot the circuit becomes by measuring the lower Vd4 and higher current. This measurement can be compared with a thermometer reading to assess the accuracy of this method. Prelab Exercises 1) Reconsider the design of the common-emitter amplifier of Fig. 3. With all design parameters remaining the same, how large may the collector resistor be such that the collector-base junction remains reverse-biased (assume that this reverse bias must be at least 200 mV)? 2) Reconsider the design of the common-emitter amplifier of Fig. 3, this time assuming finite (i.e., collector and emitter currents are not equal, and base current is not zero) and that the 1mA specification refers to the collector, not emitter, current. Determine expressions for the four resistors in terms of . Evaluate these expressions for = 50, 100, 200 and infinity, and comment qualitatively as to the sensitivity of these values on . 3) Reconsider the design of the common-emitter amplifier of Fig. 3, this time assuming arbitrary V be (i.e., in your equations, use the symbol Vbe rather than 700 mV). Determine expressions for the four resistors in terms of Vbe. Evaluate these expressions for Vbe = 600 mV, 700 mV and 800 mV, and comment qualitatively as to the sensitivity of these values on V be. What causes greater changes in resistor values, Vbe or ? 4) 5) 6) Consider the current mirror of Fig. 4. Assume you desire the current in Q 2 to be 2.4 times that of the reference transistor. What is the required emitter resistor for Q2 (assuming R1 = 1k)? To get a feel for the error involved in this design, assume that the reverse saturation current for Q 2 is 25% smaller than that of Q1 and that T = 300K (i.e., room temperature). Evaluate the error term as a percentage of the desired current. Is this acceptable assuming you want less than 1% error? To reduce the error by a factor of 5, what new resistor values are required? Lab Exercises 1) Build the common emitter amplifier of Fig. 3. Measure Vbe in the lab. Using your equations from prelab exercise 3, adjust your resistor values based on the measured V be. Is the collector current now 1 mA? Measure the voltage across the collector and emitter resistors as well as the resistors themselves, and from this deduce the of the transistor. 2) Build a current mirror that is supposed to deliver a current of 2.4 mA (append a load resistance up to the supply). Measure the emitter resistors carefully and try to implement the correct ratio as close as possible. Measure the output current, and determine the percentage by which it is off from the ideal value. Increase each of the emitter resistors by a factor of 5, and measure the currents through both transistors. Is the ratio closer to 2.4 than before (that is, did the error get smaller)? Did the error go down by a factor of 5 roughly? 3) Build the voltage regulator of Fig. 5. Append a load resistance, and measure the output voltage as you vary the load resistance from 100 to 100k. 4) Build the thermometer circuit. Use a battery of 3.5V and 4.5V along with a mercury thermometer reading of room temperature to determine empirical values for V go and ln(Io). Now that you have calibrated your thermometer circuit, apply a heat gun to the circuit, and measure V d4 and the current (you may need to wait a while for the circuit to reach thermal steady-state, since the temperature doesn’t change instantaneously). Once the voltage and current have settled, determine the temperature of the circuit from the equation you derived in the prelab. Does the voltage across the diodes display a negative temperature coefficient, i.e., does the voltage go down with increased temperature? Compare the temperature calculated with that measured with a mercury thermometer.