DIGMAP - Discovering our Past World with Digitized Historical Maps

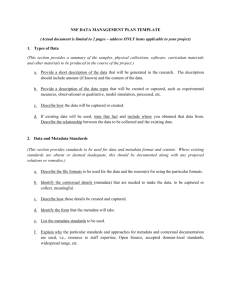

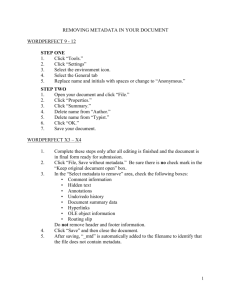

advertisement

Alberto Fernández Wyttenbach is Technical Surveying Engineer (BSc.) and currently student in Geodesy and Cartography Engineering (MSc.) at the UPM - Technical University of Madrid (Spain). He is a granted student at LatinGEO - Laboratory of Geographic Information Technologies (UPM), where he has collaborated in several national and international projects. He is specialized in Historical Cartography on Web and digitalization techniques in Cartographic Heritage. Mabel Álvarez López is BSc and Land surveyor, with the following postgraduate studies: Land Information Systems (Holland); Technical and Organizational Management (Italy) and Strategic Planning and Management of Land Administration and Gorgraphical Information Organisations (Sweden). Currently is: Professor at National University of Patagonia (Argentina), Director of a Provincial Public Administration with functions in municipal affairs, Editor of the SDI IberoAmerica Newsletter and researcher in four international projects Miguel Ángel Bernabé Poveda is BSc. in Land Surveying, a Master in Fine Arts and PhD. in Education. Professor at UPM Technical University of Madrid (Spain), where he held the Head of the Surveying Engineering and Cartography Department (20002005). Currently, he is Head of the LatinGEO - Laboratory of Geographic Information Technologies (UPM). He is specialized in Cartographic Design, Semiotics of Maps, Spatial Data Infrastructures, Usability and Ergonomics of Geo-Portals. José Borbinha has a PhD. in Informatics Engineering by the IST Instituto Superior Técnico in Lisbon (Portugal). He is Assistant Professor in the Computer Department (IST) and Researcher in the INESC-ID Information Systems Research Group, where he specialized in Digital Libraries Architectures. He has held the coordination of the Innovation and Development Services in the National Library of Portugal (1998-2005). He is Consulter in the Information Society and Technology Programme of the European Commission (EC), and of the National Science Foundation (USA). Founder Member of the IEEE TCDL – Technical Committee on Digital Libraries. DIGITAL MAP LIBRARY SERVICES IN THE SPATIAL DATA INFRASTRUCTURE (SDI) FRAMEWORK: THE DIGMAP PROJECT (1) (2) (3) A. Fernández-Wyttenbach , M. Álvarez , M. Bernabé-Poveda , J. Borbinha Technical University of Madrid, Spain (1) (2) (3) Instituto Superior Técnico de Lisboa, Portugal a.fernandez@topografia.upm.es (1) mablop@speedy.com.ar jlb@ist.utl.pt (2) (4) (4) mab@topografia.upm.es (3) (4) Keywords: Cartography; Metadata; SDI; DML; Internet; History; Heritage; OGC services. 1. INTRODUCTION There are several cooperative projects aiming at the widespread distribution of historical cartographic funds in the Web through geographic localization tools, engaging various national and international institutions. It is the case of the AfriTerra Project [1], the DHM Digital Historical Map European Project [2] and the Digital Library of Portuguese Urban Cartography [3]. Scientific advances are made through international, informative forums and meetings in which these new technologies, as applied to historical cartography, are presented and discussed. The Electronic Cultural Atlas Initiative (ECAI) [4] is certainly the most relevant, followed by the recently created ICA Working Group on Digital Technologies in Cartographic Heritage [5]. Besides, many visualization tools and digital technologies have been developed so far, such as the TimeMap OpenSource software [6] from the University of Sydney, or the famous cooperative Google Earth 3D Globe Project. [7] Fig 1: Historical map application in Google Earth 3D Globe There are also organizations gathering together map library professionals who could support the setting-up of discussions and exchange of knowledge and policies to follow in the acquisition, conservation, cataloguing and dissemination of public cartographic collections (LIBER [8], IBERCARTO [9], TEL [10], ISCEM [11], BSC [12], etc.). Nevertheless, it seems that no cooperative projects have been set off so far by a group of map libraries to simultaneously and remotely access several historical cartographic funds. As a matter of fact, it would seem useful to have a tool allowing remote access to a GI repository from a single Website. This solution would facilitate access to information and the comparison of some documents located in different servers, providing access to funds through the creation of cataloguing and visualization Web tools, hence the importance of being able to access all available information remotely through a Digital Map Library (DML) abiding by the Spatial Data Infrastructure (SDI) guidelines. Taking advantage of the INSPIRE case to promote European cooperative policies; other European projects are already under way, such as DIGMAP (described below). 2. THE SDI FRAMEWORK From a technological viewpoint, an SDI combine distributed data and services by an interoperable way to be used in traditional GIS or in geoportals within various geoprocessing and utility stages. Thus, a decentralized, transparent model is developed for users, based on data harmonization, compatibility and interoperability of the systems in which several players take part: providers, advisers, integration processors, managers and users. [13] 2.1 Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC) Services [14] Several well known standardized services rely on commercial options and OpenSource for their implementation. The OGC has a close relationship with ISO/TC 211, the Technical Group which has developed the ISO 19100 standardization series in the field of digital GI. Its work aims at establishing a structured set of standards for information concerning objects or phenomena that are directly or indirectly associated with a location relative to the Earth. The specifications empower technology developers to make complex spatial information and services accessible and useful with all kinds of applications. However, at the present time the main technical problems still have to do with the integration of clients accessing the distributed services in the SDI nodes [15]. The most important OGC specifications to the cartographic heritage field are: - WMS – Web Map Service. [16] It allows access to GI for visualization and simple queries. The data itself is not accessed, but an image of the GI is obtained that may contain information of several laid over and conflated raster or vector layers, with a single image as a result. WMS may be invoked through a Web browser by submitting a URL type request. - WFS – Web Feature Service. [17] It solves the problem of the inconsistent building of requests and the receiving of Web service vector information. It enables de user to query and retrieve geospatial vector data from multiple Web Feature Servers by using Internet as a platform. - CSW – Catalogue Service on the Web. [18] It allows publishing and searching of information describing data (metadata), services, applications and all kinds of resources at large. Catalogue Services are necessary to provide searching and invoking capabilities on the registered resources. 2.2 Geographic Metadata Metadata is the data about the data; therefore it is information and documentation making data identifiable, understandable and readily shared by users on the long term. In a geographic context, ‘metadata’ means information describing spatial data sets and spatial data services and making it possible to discover, inventory and use them. [23] Several initiatives or profiles within the field of GI may be mentioned: - ISO 19115 “GI - Metadata”. [19] International Standard of Metadata belonging to the ISO 19100 family, developed by the ISO TC/211, providing a metadata model and setting up a common set of terms, definitions and extension procedures for metadata. - Dublin Core Metadata Initiative. [20] Open forum devoted to the development of standards for general purpose metadata. Its main activities are the development of working groups, comprehensive conferences, workshops and the practice development in the field of metadata. This initiative has defined 15 basic, essential items to describe any resource (file, map, book, etc.). - NEM - Spanish Metadata Core Profile. [21] Owing to the fact that the application of the International Standard of Metadata ISO19115 “GI – Metadata” is intricate and often problematic, in many sectors, regions and countries there has been a tendency to define profiles and minimum sets of compulsory or recommended fields. NEM is an ISO 19115:2003 profile which has been approved by the Higher Geographic Council of Spain. It represents the minimum set of metadata advisable to be considered by its usefulness and relevance. The NEM Profile is made up of elements of the Core ISO 19115:2003 “Metadata” and ISO 15836:2003 “The Dublin Core Metadata Element Set”. It also takes into account the most relevant current projects in this matter, especially the Water Guideline Framework and the regional SDI initiatives [22] 2.3 Geographic Information Policies and Agreements Spatial Data Infrastructures need not only metadata, data sets, spatial services and interoperable technologies, but also agreements to share information, and to coordinate and monitor the processes. The best example on SDI agreement is the INSPIRE Directive [23] which laid down general rules aimed at the establishment of the Infrastructure for Spatial Information in the European Community, for the purposes of Community environmental policies and activities. This Directive shall cover Reference and Thematic spatial data sets. It is the first step of a wide multilateral initiative initially paying attention to the necessary spatial information for environmental policies and in other sectors. So far, SDIGER [24] has been the pilot project on the implementation of the Infrastructure for Spatial Information in Europe (INSPIRE), which aims at demonstrating the feasibility and advantages of the solutions for sharing spatial data and services, and to find the problems and obstacles of implementing interoperability-based solutions on the basis of real cases. It consists in the development of a Spatial Data Infrastructure (SDI) to support access to GI resources concerned with the Water Framework Directive (WFD) [25] within an inter-administration and cross-border scenario. SDIGER’s interest has not been to build a usual thematic SDI (Hydrology), but to study the questions of cross-border integration and high availability. [26] But a national SDI covering the three levels –national, regional and local is needed, as well as policies, coalitions and agreements in order to enhance availability, accessibility and harmonization of geographic data. An example is the SDI of Spain (IDEE) [27] which aims to integrate through the Internet the data, metadata, services and geographic type of information produced in Spain. 3. SPECIAL REQUIREMENTS OF DIGITAL MAP LIBRARY SERVICES Apart from the characteristics common to all SDIs in any thematic field, there is a number of technological and policy considerations to be taken into account, since they make the old cartography contained in the DMLs into an exceptional case within the generic frame of an SDI. 3.1 Policies and Data Sharing Schema The example of INSPIRE as an SDI for GI as applied to the environment is a good case in point for high level community policies among environmental and GI authorities to follow and carry out cooperation agreements between libraries and archives. However, the cartographic heritage is not to be included within the thematic information layers of INSPIRE. Two main problems make it difficult: 1- The policies operating in the environmental– GI scope among the various European and world agencies are clearly different from the ones operating in the cultural– heritage scope. This is not only due to the fact that the latter is more restrictive as far as property rights and data comparison is concerned, but also because the people involved are quite different. Therefore it is necessary to plan coordinating measures among multidisciplinary teams of qualified professionals: historians, librarians, computer scientists, cartographers, etc. 2- At the time of distinguishing the different hierarchical levels of the traditional SDI umbrella, the impossibility of harmonization with the cartographic heritage appears evident. This is due to the fact that while an SDI in a local environment only holds information about its geographic extent, the case of a cartographic heritage SDI (local DML) is quite different because the map collections are available in a local library where GI of any part of the world is represented. Thus, local DMLs represent a different geographic reality making up a “new” past world, and at the same time there will always be documents of a geographic region distributed throughout the map libraries of the world, clear evidence of content heterogeneity. In addition, it just so happens that contents may be repeated in many instances, though unlike other types of GI, this fact does not imply the contents should be restricted or hierarchized, since access to the entire information should be offered in spite of its repetition. It should then be noted that any local DML will offer its data through a world browser –which never occurs in the case of local, traditional SDIs. On the contrary, both local and global DMLs need to be supported by a world SDI giving them modern GI coverage. Fig. 2: SDI & DML policies and data sharing schema From an operative viewpoint, it is not possible to start off by creating a world DML, nevertheless DML growth in line with the traditional SDIs should be tried following the open path. The strategy to follow consists of creating DMLs in a local environment. The interoperability provided by the standards and metadata should always be taken into account. Thus, it will be possible from there to work up links with other map libraries or to group all of them in a wider distributed information system, as is the case of the national SDIs, which have already reached a high level of development, with a schema of a national geoportal distributed to the lower level local geoportals. These local DMLs will nourish the higher levels –national and regional DMLs, until little by little the last link of the pyramid is achieved –the world DML. There are only two one-way relationships between the reality of an SDI with its traditional concept (a “real world” SDI) and the reality of a DML or SDI applied to the ancient world (a “past world” SDI). In order to take in all the existing funds of a particular geographic region through a local SDI or a local DML, the need for global information of their counterparts (global DML and global SDI respectively) must be taken into account. These two relationships are the only ones ensuring total access to the information, giving clear proof of the problem of the content geographic jurisdiction that exists between both realities. 3.2 Descriptive Metadata One of the main functions of a DML is to make use of the metadata describing the maps which are stored. Maps catalogued in libraries have been usually described according to generic bibliographic metadata schemas such as UNIMARC or MARC21; more recently, Dublin Core descriptions have been also produced (it is a simpler schema, but easier to use). Therefore it is necessary to define the appropriate gateways for these descriptive profiles to be understandable among themselves, which is a rather complex undertaking. It is convenient to use an ISO composed subset of profile elements such as the Spanish Metadata Core Profile. It provides an “open mind” metadata template and establishes a common GI metadata terminology, assuring metadata interoperability and harmonization. Several instances of OpenSource software have been developed for the geographical metadata creation and edition. CatMDEdit [28] has got a compatible multilingual interface with several metadata profiles. Some special features of the historical map set should be considered during metadata creation. Most maps include only graphic scales, so it is necessary to find the analytic value measuring the graphic scales within pixel units for them to be catalogued. Besides, the measuring units are not homogenous (metre, mile, toesa, Spanish feet, English feet, etc.). The map titles should be catalogued maintaining archaic linguistic peculiarities to avoid deleting some data information, but correction is advised when filling the summary metadata field in order to refine the queries. The use of multilingual thesauri and gazetteers which support metadata creation and the development of ergonomic search interfaces for data and service catalogues are necessary. They may be used during metadata automatic indexing as a term is related to a geographic extension. [29] When carrying out georeferenciation, we should take into account that it conveys the risk of deformation of documents of historical interest against the advantages of their publication together with other data in the Web. This should be an important consideration when dealing with distinct kinds of users who would utilize cartographic funds for different purposes. It is generally recommended to provide bounding box approximate coordinates so as to avoid image distortion. 3.3 Image processing It is interesting to point out that further image processing should be avoided as much as possible so as not to unintentionally hide or delete some information from the original document. However, the precarious conditions of some maps sometimes make necessary to use plastic covers that would avoid accidents during the scanning. That leads to plastic ledges in the images that do not belong to the original document which need to be processed and refined. Besides, some maps sometimes are taken apart in pieces and they have to be reconstructed. [30] In the storage process it is interesting to consider compression formats, which bear high compression ratios and good performance in the information access; making Internet publication easier, particularly when working with a huge number of documents or high resolution workpieces. 4. THE DIGITAL MAP LIBRARY PROTOTYPE Some specific experiences have been carried out by the Technical University of Madrid in this field, trying to include the DML services in a local SDI prototype. The DML of the Canary Islands, [31] studied in depth the creation of an Internet portal with access to a Map Server and a catalogue containing the historical maps and plans of the Canary Islands which normally have a very limited access. Visualization and query tools were used from standardized OGC Services (WMS, WFS, CSW) allowing visualization and comparison of any maps as well as access to their metadata. The digitized and georeferenced documents can be visualized and requested through a Web Map Server using the MapServer OpenSource software [32]. The Web client is based on HTML/JavaScript language and it was designed to access the WMS. This interface allows visualizing the requested results sent to the server by the OGC specification protocol. The external cartographic base is combined with raster and vector layers which can be visualized through the Web interface, including the island contour and the tiles generated with the document contours. This application allows different types of search with the approximate contour of each map, and over the cartographic base. Besides, the metadata of the maps were included in a geographic catalogue [33] [34]. Thus, it is possible to include advanced searches with the GeoNetwork OpenSource software according to the ISO23950 standard. [35] Fig. 3: Digital Map Library Prototype of the Canary Islands 5. THE DIGMAP PROJECT DIGMAP [36] is a project co-funded by the EC eContentplus Programme, [37]. It started in October 2006 and will run for 24 months. The project will reuse contents (digitised maps; related resources and metadata) from the National Library of Portugal (BNP) [38], the Royal Library of Belgium (KBR) [39], the National Library of Italy in Florence (BNCF) [40], the Spanish Geographical Institute (IGN-E) [41] and the National Library of Estonia (NLE) [42], in order to produce new services for searching and browsing). Latter, the collection will be extended with resources from other libraries, archives and information sources, namely from the other European National Libraries members of TEL - The European Library [43]. DIGMAP will explore environments for browsing and searching by human users, as well as services for interoperability with external information systems. The information system will be designed and developed according to a SOA - Service Oriented Architecture, using existing open-source technology and new technology to be developed in the project. That will comprise techniques for the automatic extraction of metadata from images of digitized maps, digitized books and Websites, gathering of metadata from remote services, etc. The software solutions to be produced will be able to be reused in other digital libraries, for standalone services, or as components integrated with other digital libraries. In this sense, the information architecture will follow open data models, namely those already defined or to be defined by the OGC, IFLA [44] or other relevant international organisations. The technology will be developed by the Department of Computer Engineering of the Instituto Superior Técnico of Lisbon (IST), [45] in cooperation with the Laboratory of Geographic Information Technologies of the Technical University of Madrid (UPM). [46] Three specific results will be highlighted, an “International Catalogue of Digitized Ancient Maps”, an “International Authority Database of Map Engravers, Editors and Printers” and a “European Multilingual Geographic Thesaurus”. The experimental results are expected to help also the promotion of European collaborative networks and policies for reference, description, cataloguing, indexing and classification of ancient maps. 5.1 Service Prototype The first year will produce a service prototype. The focus will be to demonstrate that the consortium can deal properly with the bibliographic records from multiple sources and to validate the generic use cases. A special focus will be given the use case Searching Resources (with sub-use cases Searching Simple and Searching Advanced). This service will be developed as a traditional OPAC - Online Public Access Catalogue, but now focused on the specificities of the resources. Browsing by toponymy might be possible, at least at a high level and based only on the information extracted from the bibliographic metadata. Spatial browsing will be provided only in the second year. Global Use Cases Searching Resources Updating Thesaurus Geographer External System Brow sing Resources Updating Catalogue Updating Authorities User Proposing Resources Cataloguer Dispatching Questions Asking an Expert Registered User Managing Serv ices Administrator Fig. 4: DIGMAP first level use cases Relevant standards and technology will be used in the first DIGMAP Service Prototype for descriptive metadata (mainly UNIMARC, MARC21 and Dublin Core), GI (ISO 19000 family of standards), Thesauri (ISO 5964 - Guidelines for the Establishment and Development of Multilingual Thesauri) and Core Technology (Web-Services, OAI-PMH, RDF, XML Schemas, etc.). Finally, DIGMAP will work towards the goal of becoming the main international information source and reference service for old maps and related bibliography. The targeted users of the services are citizens, students, scholars, teachers, professionals in libraries, archives, and technology, as well as institutions intending to provide similar services, such as other national, university and research libraries, archives, etc. 6. CONCLUSIONS - Digital Map Library services represent a new concept within the Spatial Data Infrastructure as applied to the cartographic heritage. - There are useful and basic similarities between the global reality of a Spatial Data Infrastructure in its well known traditional concept and a Digital Map Library; according with standards, agreements and services. But it also means new requirements regarding policies, with a new schema of geographic integration of the historical contents that must be reasoned and heuristically assessed; in order to carry out an in-depth study of Digital Map Library usability within the SDI framework. [47] - It is essential to follow the progress path of the Spatial Data Infrastructures and to start building agreements and cooperative projects of interoperable local Digital Map Libraries, without neglecting the future global Digital Map Library. - DIGMAP comes up as a case in point in the creation of a European Digital Map Library in parallel to INSPIRE, the European Spatial Data Infrastructure. It should be a case in point and an example to be disseminated throughout the world, particularly in Europe and America. - Among the decisions to be taken to maintain the historical and geometric rigour of maps, we should highlight the greater importance of chronological accuracy and the metadata at large than the georeferenciation as such. - Georeferenciation and image handling may greatly alter maps, many of their qualitative features may get lost. This fact should be borne in mind according to the user profiles. - In view of the diversity of tasks and processes involved in the development of a Digital Map Library, it is indispensable to work with a qualified, multidisciplinary team, of professionals: librarians, historians, computer scientists, etc. monitored by a cartographer. - Application of the new technologies in the creation of a Digital Map Library leads to the development of the necessary tools for both professionals and amateurs to be able to work and enjoy old cartography for the benefit of the upkeep and public knowledge of the cartographic heritage. 7. REFERENCES [13] Mas S. (2006): “INSPIRE y la Infraestructura de Datos Espaciales de España (IDEE): componentes, actores, datos y su desarrollo a través de organizaciones o programas específicos”. Technical Session: The INSPIRE and Spanish SDI (IDEE) development; and its application to the Higher Council of Scientific Research (CSIC). June, 8 2006. http://www.ieg.csic.es/sigJornadas/html/ [15] Béjar, R.; Muro, P. (2006):“Tecnología e Implantación de Infraestructuras de Datos Espaciales. Ejemplo del Proyecto Piloto SDIGER”. Technical Session: The INSPIRE and Spanish SDI (IDEE) development applied to the High Council of Scientific Research (CSIC). June, 8 2006. http://www.ieg.csic.es/sigJornadas/html/ [26] Nogueras, J.; Latre, M.; Béjar, R,; Muro, P.; Zarazaga, F. (2005): “SDIGER: Experiences and identification of problems on the creation of a transnational SDI”. Proceedings of the Technical Conference of the Spatial Data Infrastructure of Spain” (JIDEE). Madrid, November, 24-25 2005. [22] Ballari, D.; Sánchez, A; Nogueras, J.; Rodríguez, A; Bernabé, M. (2006): “Measures Aimed at Enhancing the Use of the Spanish Metadata Core Profile” 9ª GSDI Conference. November, 3 2006. (Chile) [29] Martins, B.; Silva, M.; Freitas, S.; Alfonso, A. (2006): “Handling Locations in Search Engine Queries”, Workshop on Geographic Information Retrieval at SIGIR, August 2006 [30] Wyttenbach, A. F.; Ballari, D.; Manso, M. A. (2006): “Digital Map Library of the Canary Islands”. e-Perimetron: International Web Journal on Sciences and Technologies affined to History of Cartography (http://www.e-perimetron.org). Vol.1, No. 4. Autumn 2006. Pág.262-273. ISSN 1790-3769. [34] Manso, M. A.; Bernabé, M. A. (2004): “Prototipo de GeoPortal de mapas antiguos”. Proceedings of the Technical Conference of the Spatial Data Infrastructure of Spain” (JIDEE). Madrid, November, 4-5 2004. [46] Hom, J. (1998): “The Usability Methods Toolbox”, http://usability.jameshom.com/ 8. WEB SITES [1] AfriTerra Project. http://www.afriterra.org/ [2] DHM - Digital Historical Map Project. (INFO2000 EU Programme). http://www.dhm.lm.se/ [3] Arquivo Virtual de Cartografía Urbana Portuguesa. http://urban.iscte.pt/ [4] ECAI - Electronic Cultural Atlas Initiative. http://www.ecai.org/ [5] Working Group on Digital Technologies in Cartographic Heritage of the International Cartographic Association (ICA), http://web.auth.gr/xeee/ICA-Heritage/ [6] TimeMap OpenSource. http://www.timemap.net [7] Google Earth 3D Globe Project, http://earth.google.com/ [8] LIBER - Ligue des Bibliothèques Européennes de Recherche. http://www2.kb.dk/liber/ [9] IBERCARTO - Grupo de Trabajo de Cartotecas Públicas Hispano-Lusas. http://www.sge.org/ [10] TEL - The European Library, www.theeuropeanlibrary.org/ [11] ISCEM - International Society Curators of Early Maps http://cartography.geo.uu.nl/mapsoc/iscem.htm [12] Map Curators' Group of the British Cartographic Society, http://www.cartography.org.uk/ [14] OGC - Open Geospatial Consortium. http://www.opengeospatial.org [16] OGC “OpenGIS Web Map Server Implementation Specification” Version: 1.3.0 Open GIS Consortium Inc. Date: 15-March-2006- Reference number of this OpenGIS project document: OGC 06-042. [17] OGC “OpenGIS Web Feature Service Implementation Specification” Version: 1.1.0 Open GIS Consortium Inc. Date: 3-May-2005- Reference number of this OpenGIS project document: OGC 04-094 [18] OGC “OpenGIS® Catalogue Services Specification” Version: 2.0.2 Open GIS Consortium Inc. Date: 23-February-2007- Reference number of this OpenGIS project document: OGC 07-006r1. [19] ISO 19115-FDIS. Geographic Information – Metadata, 2003. [20] Dublin Core Metadata Initiative. http://dublincore.org/ [21] NEM - Núcleo Español de Metadatos. http://www.idee.es/resources/recomendacionesCSG/NEM.pdf [23] Directive 2007/2/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 March 2007 establishing an Infrastructure for Spatial Information in the European Community (INSPIRE). http://www.ec-gis.org/inspire/directive/l_10820070425en00010014.pdf [24] SDIGER Project. http://www.sdiger.net/ [25] WFD - Water Framework Directive. http://ec.europa.eu/environment/water/ [27] IDEE – Infraestructura de Datos Espaciales de España. http://www.idee.es [28] CatMDEdit - http://catmdedit.sourceforge.net/ [31] Digital Map Library of the Canary Islands (WMS), http://mapas.topografia.upm.es/cartotecanarias [32] MapServer. http://mapserver.gis.umn.edu/ [33] Digital Map Library of the Canary Islands (Catalog), Catalog project. http://mapas.topografia.upm.es:9090/geonetwork [34] GeoNetwork Geographic Metadata http://sourceforge.net/projects/geonetwork [35] DIGMAP - Discovering our Past World with Digitised Maps (Programme eContentplus – Project: ECP-2005-CULT-038042), http://www.digmap.eu/doku.php [36] eContentplus Programme. http://europa.eu.int/information_society/activities/econtentplus/ [37] BNP - National Library of Portugal, http://www.bn.pt/ [38] KBR - Royal Library of Belgium, http://www.kbr.be/ [39] BNCF - National Library of Italy in Florence, http://www.bncf.firenze.sbn.it/ [40] IGN-E - Spanish Geographical Institute, http://www.ign.es/ [41] NLE - National Library of Estonia, http://www.nlib.ee/ [42] IFLA - International Federation of Library Associations, http://www.ifla.org/ [43] DEI/IST – Department of Computer Engineering (Instituto Superior Técnico), http://www.dei.ist.utl.pt/ [44] LATINGEO - Laboratory of Geographic Information Technologies (Technical University of Madrid). http://www.latingeo.net/ [45] IMI - Institute of Mathematics & Informatics (Bulgarian Academy of Sciences) http://www.math.bas.bg/