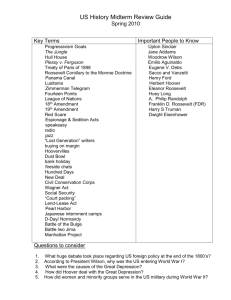

second semester review on chapters 14 to 31

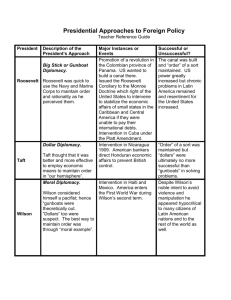

advertisement