Chmielewska Marzena

advertisement

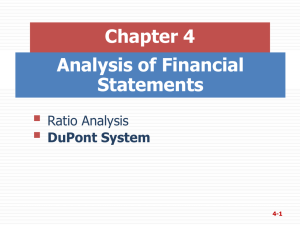

THE RETURN ON EQUITY (ROE) FOR FOOD SECTOR COMPANIES LISTED ON THE WARSAW STOCK EXCHANGE dr hab. Sławomir Juszczyk, Warsaw University of Life Sciences (SGGW), Poland slawomir_juszczyk@sggw.pl mgr Artur Jan Nagórka, Warsaw University of Life Sciences (SGGW), Poland artur_nagorka@sggw.pl ABSTRACT The key systematic issue tested throughout this paper is finding the reason for the relative low representation of the food sector on the stock exchange. Research on the performance of food sector companies within 1998–2008 led authors to the conclusion that one of the potential reasons of such under representation might be low level of ROE relative to the return from available investment opportunities made at the market free risk rate during the matching period. Polish investors enjoy a large scope of investment options, some relatively safe and capital market risk free, including a number of Treasury Bills and Treasury Bonds. Key thesis in this paper show substantial discrepancy between the level of return (ROE) on Polish listed food sector companies and the level of return acceptable for investors. For the purpose of the research the authors used several available ways to calculate ROE and compared in this paper to the market risk free rates for the period. Results clearly confirm that ROE of food sector companies remains on lower levels than the market risk free rates, sometimes even remaining on negative territories. Keywords: Return on Equity ROE, stock exchange, food sector, market risk free, INTRODUCTION The problem of the financial result worked out basing on assets used by the company is present in the practice of corporate finances since the 30's of the XX century, when the pioneer works were conducted in the financial division of the chemical giant Du Pont. The general practice of comparing appropriate elements from companies’ financial statements and on these basis calculating appropriate measurements of the companies’ performance thus has taken the name of Du Pont system. While describing the issue, authors use sometimes different taxonomy: „Du Pont system” (Ross, Westerfield, Jaffe, 1990, p.42 – 44), (Bodie, Kane, Marcus, 2009, p. 636 – 641), (Brealey, Myers, Marcus, 2001, p. 142 – 146), „Du Pont model” (Brigham, Daves, 2007, p. 259 – 270), „Du Pont equation” (Brigham, Ehrhardt, 2008, p. 132 – 141), while "Du Pont pyramid" is generally used term in Polish language literature. Within the Du Pont system there are three ratios related to defining return: ROS - Return On Sales, ROA - Return On Assets, and ROE - Return On Equity. The most important for the company’s owners is the third ratio which shows how efficiently equity (what in reality is the owners own capital invested in the company) has been used by the company. There are several approaches to which level of the result of the company’s business shall be used for the most relevant calculation of the return shall be measured (i.e. what to use as a numerator). It is sure that it should be one of the forms of earnings or profit but the concepts vary starting from the level of net profit to the level of EBIT. In the case of ROE the majority agrees that the numerator should consist of the net profit what in general practice is equal with net profit payable to the owners. However there is a view (Garrison, Noreen, Brewer, 2008, p. 724 – 727) that the numerator should be clearly calculated as net profit corrected by the payment of preferred dividends. This is largely unimportant for the concept of ROE and secondly the voice is an isolated one. As far as denominator is concerned it is crucial to use a correct figure for equity. The first concept is that it should be the level of equity as stated for the last day of the accounting period. This view was largely present at the initial stages of the development of the concept of ROE (Bień, 2008, p. 99 - 103), (Micherda, red., 2005, p. 63 - 66), (Pastusiak, 2009, p. 99 101), (Sierpińska, Jachna, 1996, p. 103 - 107), (Siudek, 2004, p. 185 - 187), (Wędzki, 2003, p. 20 - 23), (Bodie, Merton, 2003, p. 121 - 130), (Brigham, Houston, 2005, p. 119 - 122), (Adair, 2006, p. 46 - 47), (Bodie, Kane, Marcus, 2009, p. 636 - 641), (Brigham, Daves, 2007, p. 259 - 270), (Brigham, Ehrhardt, 2008, p. 132 - 141), (Damodaran, 1996, p. 79 - 86). Alternatively, it is acceptable to argue that the applicable correct figure for the equity shall be calculated as the simple average of the two consecutive accounting periods, the current and the previous one. This point of view becomes more and more generally recognised since it is acknowledged that the average for the year (the beginning and the end of the accounting period figures) describes the condition of the company more precisely that the fixed figure of the year end (Brealey, Myers, 1999, p. 1083 - 1087), (Bodie, Merton, Cleeton, 2009, p. 83 88), (Brealey, Myers, 1991, p. 680 - 682), (Brealey, Myers, 2003, p. 828 - 831), (Brealey, Myers, Marcus, 2001, p. 142 - 146), (Garrison, Noreen, Brewer, 2008, p. 724 - 727), (Harrington, Wilson, 1989, p. 8 - 16), (Ross, Westerfield, Jaffe, 1990, p. 42 - 44). USAGE OF ROE In short and simplified summary, the ROE ratio shows the company’s ability to generate profits through the period using available means, i.e. the equity. In practice there may be some difficulties in using ROE as a comparison tool to judge the performance of the company – mainly because of the weakness of the net profit parameter which is the accountancy figure versus the real money worked out by the company as shown in the cash flow. Thus net profit is rather more a paper figure than real money in the company's disposal. Because of different law systems and various numerous tax exemptions plus different manners to count depreciation and amortization it is difficult to use ROE ratio as a simple comparison between the companies. It is similarly difficult to use ROE to compare companies from different sectors which have different capital needs. ROE in % in various sectors in 2007: Cigarette Industry 35,0 Iron/Steel making 26.7 Soft Drinks 19,2 Banks 17,1 Data storage 16,5 Farm products 16,5 Software for business 12,8 Telecommunication 12,3 Food 11,8 Airlines 8,5 Source: Bodie, Kane, Marcus, 2009, p. 568, from Yahoo! Finance of 5.11.2007 There are other issues that influence usage of ROE (Brigham, Houston, 2005, p. 135) related to business risk, scale of activity and project implementing. Because of its construction, ROE ignores the risk factor. It is possible that a very risky project, that in one accounting period was very successful, in the next period is much worse. In this respect, judging through the past, it would have been better to choose the project with inferior ROE but with a significantly higher risk that would enable generating profit in the long run. The ROE ratio does not take into account the scale of the project. There are various cases where the high level of ROE is possible to achieve only when investing in projects of lower scale (i.e. not using whole available capital). Managers in such circumstances should rather decide to take on the project of lower ROE but allowing the usage of larger amount of capital. ROE is as well difficult to use when it deals with sections of an enterprise. It may happen that the managers evaluated solely on the basis of the level of ROE ratio, i.e. have a clear goal of a certain ROE level acceptable, after having reached such sufficient level for the positive evaluation of the management, are then reluctant to take risk of new projects for the fear that this would lower the achieved level of return. Important feature of ROE is that using the financial statements it is possible to calculate its level from the past (Bodie, Kane, Marcus, 2009, p. 637), but for the recommendations and assessment of the future financial events, it is advised to employ forecasts, not the historical data. Another significant remark towards ROE is the fact that it is calculated for the nominal values. The calculation for the real figures requires refining the ratio from the effect of inflation. It is particularly important from the point of view of an investor who anticipates the growth of the wealth. ROE IN FOOD COMPANIES LISTED ON THE WARSAW STOCK EXCHANGE The aim of this research is to calculate the ROE ratio in the food sector companies listed on the Warsaw Stock Exchange during the period of 1998 – 2008 and formulating using different methods of calculation and indications of its changes. In this respect authors take into consideration two basic methods of calculating ROE 1. ROE end = Net profit / Equity at the end of the accounting period 2. ROE avg = Net profit / The average of the equity from the beginning and end of the accounting period It happens that changes of the equity do not occur during the accounting period or sometimes are relatively small, however, from the point of view of dynamic character of equity and the fact that actual figures are counted in small percentage points it is better to calculate on the basis on the average equity. The food sector companies listed on the Warsaw Stock Exchange may be characterized by three subperiods within the years 1998 – 2008. 1. 1998 – 1999, when ROE was relatively at low level and in several cases it reached negative territories. 2. 2000 – 2003, when ROE was at relatively low level but the negative figures were sporadic. 3. 2004 – 2008, when ROE was at relatively higher level and the average for the sector reached double figures values. Analysis of all above companies prove that only in the period 2006-2007 all of them displayed ROE at the positive levels. In all remaining years at least one food company demonstrated the negative ROE. It is symptomatic that among 8 companies listed constantly on the Warsaw Stock Exchange within the research period, as many as 7 recorded at least once the negative ROE. There is only one company “Jutrzenka S.A.”, which ROE has been always at the positive territories, however, twice only at decimal fractions of a percent. It seems that the fact of listing on the stock exchange, the experience of the management of the publicly listed company, advise from the professional consultants and observing investors’ expectations, and in some cases extorting necessary changes in operations result in gradual growth of the ROE ratio. The periods of the negative ROE are never longer than two years and the return on the positive levels is in majority durable and the gradual consolidation is noted. For all food companies listed on the Warsaw Stock Exchange in years 1998 -2008 the ROE ratio was calculated with the implementation of both possible denominators: the amount of equity at the end of the year and the average equity for the given year. Calculating the average equity is justifiable, because the profit is made throughout the year, so one has to implement the level, that is the most close to the year average equity. Table 1. Return on Equity ROE for food sector stock listed companies Jutrzenka ROE end ROE avg 1998 7,18 7,33 1999 2,90 2,88 2000 1,85 1,84 2001 3,39 3,46 2002 0,53 0,52 (ROEend-ROEavg)/ROEavg -2,0% 0,8% 0,5% -2,2% 3,3% Mieszko ROE end ROE avg 1998 -15,83 -14,67 1999 10,48 11,06 2000 12,64 13,49 2001 2,51 2,40 2002 12,17 14,21 2004 20,73 23,60 2005 10,49 11,07 2006 12,52 13,37 9,4% -12,2% -5,3% -6,3% -16,0% -33,8% 2004 0,23 0,31 2005 2,04 2,06 2006 3,06 3,11 2007 4,26 4,36 2008 6,34 7,01 7,9% -5,2% -6,3% 18,1% -24,1% -1,0% -1,5% -2,1% -9,6% Wawel ROE end ROE avg 1998 -23,29 -20,71 1999 -49,96 -40,26 2000 8,66 9,05 2001 9,75 10,54 2002 6,94 7,09 2003 10,52 10,96 2005 25,38 29,08 2006 32,81 39,25 2007 14,25 15,34 2008 14,62 15,27 (ROEend-ROEavg)/ROEavg 12,4% 24,1% -4,3% -7,6% -2,2% -4,1% -14,7% -12,7% -16,4% -7,1% -4,3% Indykpol ROE end ROE avg 1998 1,17 1,18 1999 -7,28 -7,03 2000 8,77 10,21 2001 6,67 6,88 2002 3,46 3,52 2003 11,79 12,52 2004 16,39 17,86 2005 17,06 21,14 2006 8,81 9,21 2007 12,69 13,55 2008 -16,01 -14,83 (ROEend-ROEavg)/ROEavg -0,6% 3,6% -14,1% -3,0% -1,7% -5,9% -8,2% -19,3% -4,4% -6,3% 8,0% Kruszwica ROE end ROE avg 1998 -10,96 -13,58 1999 -73,43 -53,71 2000 7,88 9,13 2001 6,09 6,32 2002 7,56 7,86 2003 25,34 29,01 2004 19,47 21,57 2006 8,68 12,09 2007 7,36 7,35 2008 23,59 25,40 (ROEend-ROEavg)/ROEavg -19,3% 36,7% -13,6% -3,6% -3,8% -12,7% -9,7% 0,0% -28,2% 0,1% -7,1% 1998 5,10 8,97 1999 6,07 6,23 2000 1,50 1,60 2001 -0,35 -0,39 2002 7,02 3,84 2003 18,46 18,31 2004 9,74 10,27 2005 26,51 26,41 2006 35,26 30,17 2007 49,69 46,31 2008 54,32 50,82 -43,1% -2,6% -6,8% -10,5% 82,9% 0,8% -5,1% 0,4% 16,9% 7,3% 6,9% Wilbo ROE end ROE avg 1998 12,33 13,14 1999 5,33 5,33 2000 6,79 7,03 2001 1,60 1,61 2002 -7,15 -7,11 2003 2,93 2,97 2004 -2,13 -2,11 2005 -16,30 -15,07 2006 2,26 2,28 2007 9,29 9,75 2008 5,53 5,68 (ROEend-ROEavg)/ROEavg -6,2% 0,1% -3,4% -0,8% 0,6% -1,5% 1,1% 8,1% -1,1% -4,6% -2,8% Pepees ROE end ROE avg 1998 9,40 9,73 1999 -2,67 -2,64 2000 9,64 10,15 2001 1,78 1,79 2002 0,31 0,31 2003 4,46 4,57 2004 2,80 3,27 2005 -0,24 -0,24 2006 1,56 1,67 2007 85,76 71,73 2008 -1,84 -1,85 (ROEend-ROEavg)/ROEavg -3,4% 1,3% -5,0% -0,9% -0,2% -2,2% -14,4% 0,4% -6,8% 19,6% -0,5% Food sector average ROE end ROE avg 1998 -1,86 -1,08 1999 -13,57 -9,77 2000 7,22 7,81 2001 3,93 4,08 2002 3,86 3,78 2003 5,37 6,61 2005 9,80 10,99 2006 13,12 13,89 2007 26,95 25,86 2008 10,91 11,07 (ROEend-ROEavg)/ROEavg Żywiec ROE end ROE avg (ROEend-ROEavg)/ROEavg 4,5% -14,3% 2003 5,73 5,24 2003 -36,23 -30,68 2004 27,72 32,51 2004 11,87 13,41 2005 13,47 13,47 2007 32,30 38,46 2008 diff 0,71 1,07 -5,8% -3,1% -3,3% -4,7% -5,6% 4,3% -0,9% -1,1% Table 1: Return on Equity (ROE) calculated on the basis of end of the period figure and on the basis of the average for the accounting period. Source: own calculations The results showing the difference between two formulas are presented in the table in the position: difference between ROEend and ROEavg = (ROEend – ROEavg)/ROEavg x 100%. The average of these values in the consecutive 11 years is shown in the last column. For 7 among 8 researched companies this deviation is in negative territories between -5,0 and -0,9 % what indicates the systematic growth of the equity in these companies. The significant remark is that the figures obtained with the calculations using the average amount of equity are usually higher than these obtained with the calculations using the period end figures. Such a phenomenon is to be explained by the fact that the equity in companies has a general growth tendency what is in line with the real sense of the company’s existence whose aim is the maximisation of the profit from the owners capital. The part of this profit after taking off the dividend is retained in the company and in the consequence makes the equity grow. From the point of view of the investor a question arises, how to evaluate the economic gist of the investment in the food sector companies listed on the exchange. For the financial investor the return of such an investment is measured as the total of the paid dividend and the capital gains measured as the difference between the selling price and the purchase price reduced by the transaction costs. Such a view includes in itself two main factors influencing the market price of shares: the company’s financial results raising or lowering its value and the influence of general market forces not linked with the financial situation of the particular company – and these two independent factors are always interacting in the same time. If so to exclude the influence of the market forces as general, the basic factor to measure the economic meaning of the investment should remain the net profit. In the context of the capital investment it is shown in the ROE ratio. In this case the question arises to what level compare the ROE ratio in order to receive the answer for the real meaning of the investment in the given company. It is possible to compare this ratio to the level of inflation to receive the return in the real values rather than in the nominal values. This approach has a substantial limitation because the way of construction of the ratio by taking numerator and denominator from the same moment of time reduces the influence of the inflation. MARKET RISK FREE INVESTMENTS An alternative way to calculate the efficiency of the investment is to compare it with the market free risk investments. The scientists from the corporate finance domain do not agree as to the exact definition of the “market free risk investment”. In a logic sense, it means the investment at the highest return without any risk. The question of risk is crucial. It possible to assume that the instruments issued by the State Treasury or by a bank of the highest rating are the market risk free instruments. However even at the best banks and even in the case of countries there is a certain risk of insolvency. To create the market risk free investment level it is possible to calculate the average of the deposit interest for all the banks in the given economy. The solution is however not acceptable from the point of view of a real investor because as the place for creating a deposit only one or just a few banks could be used, and they may carry much higher risk than an average for all the banks. There is a possibility to use the deposit level on the interbank market as this one which is minimal to reach in the given market conditions, so in the case of Poland it may be WIBOR (Warsaw InterBank Offered Rate). The argument to reject this rate is that in the given moment it is a result of the current market forces and its employment at the date of the end of the year bares the risk of tampering with the results. Another benchmark for the market risk free investment could be one of the National Bank of Poland interest rates. Among these rates the most suitable seems to be the reference interest rate as this one which is the basis to calculate other interest rates and instruments in the national economy. The weakness of this approach lies in the fact that there are no instruments accessible for the financial investors that would use as the basis the reference interest rate. As the proper benchmark to use as the market risk free investment one can employ only the instruments issued by the State Treasury. From all of them as the market risk free one can point at the Treasury Bills and Treasury Bonds. In respect to the multitude of these papers, the fundamental question arises which of them are the best to implement. In the practice of investment banking as the most suitable one considers 52 weeks Treasury Bills or current Treasury Bonds. Treasury bills are the instruments that bare slightly lower risk but at the same time are less commonly accessible. From the above reasoning the conclusion comes that the best solution would be to use the return obtained either from 52 week Treasury Bills or from 2 years Treasury Bonds. During the research the list of returns of these bills and bonds was created and the levels were compared. The figures concern the levels from the last trades in the given calendar year. Table 2. The market risk free investment in Poland last trades in year 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 52 weeks Treasure bills 5,69 5,97 6,37 4,32 4,21 5,74 5,92 2 years Treasury bonds 5,51 6,14 6,12 4,54 4,62 6,19 5,47 difference 0,18 -0,17 0,25 -0,22 -0,41 -0,45 0,45 mean of differences total -0,05 Table 2. The market risk free investment shown as the 52 weeks T-bills and the 2 years Tbonds and the difference between them. Source: own calculations In the header of the table the years are put in the meaning of the date of the last trading session for the given year. In the lines of the table there are: return on 52 weeks T-bills, return on 2 years T-bonds, the difference of these instruments in the percentage points, the mean of the differences in the percentage points. The above conducted calculations show that the long term difference between the return of 52 weeks T-bills and the 2 years T-bonds is negligible, sometimes the first is higher, sometimes the second, and the mean of the differences for the whole period is very small and amount to only 0,05 of a percentage point. Table 3. The return on equity ROE versus the market risk free investment Jutrzenka ROE end Market risk free basis end 1998 7,18 12,59 1999 2,90 15,83 2000 1,85 17,26 2001 3,39 10,84 2002 0,53 5,69 2003 5,73 5,97 2004 20,73 6,37 2005 10,49 4,32 2006 12,52 4,21 2007 32,30 5,74 2008 0,71 5,92 ROE avg Market risk free basis avg 7,33 18,33 2,88 14,21 1,84 16,55 3,46 14,05 0,52 8,27 5,24 5,83 23,60 6,17 11,07 5,35 13,37 4,27 38,46 4,98 1,07 5,83 Mieszko ROE end Market risk free basis end 1998 -15,83 12,59 1999 10,48 15,83 2000 12,64 17,26 2001 2,51 10,84 2002 12,17 5,69 2003 -36,23 5,97 2004 0,23 6,37 2005 2,04 4,32 2006 3,06 4,21 2007 4,26 5,74 2008 6,34 5,92 ROE avg Market risk free basis avg -14,67 18,33 11,06 14,21 13,49 16,55 2,40 14,05 14,21 8,27 -30,68 5,83 0,31 6,17 2,06 5,35 3,11 4,27 4,36 4,98 7,01 5,83 Wawel ROE end Market risk free basis end 1998 -23,29 12,59 1999 -49,96 15,83 2000 8,66 17,26 2001 9,75 10,84 2002 6,94 5,69 2003 10,52 5,97 2004 27,72 6,37 2005 25,38 4,32 2006 32,81 4,21 2007 14,25 5,74 2008 14,62 5,92 ROE avg Market risk free basis avg -20,71 18,33 -40,26 14,21 9,05 16,55 10,54 14,05 7,09 8,27 10,96 5,83 32,51 6,17 29,08 5,35 39,25 4,27 15,34 4,98 15,27 5,83 Indykpol ROE end Market risk free basis end 1998 1,17 12,59 1999 -7,28 15,83 2000 8,77 17,26 2001 6,67 10,84 2002 3,46 5,69 2003 11,79 5,97 2004 16,39 6,37 2005 17,06 4,32 2006 8,81 4,21 2007 12,69 5,74 2008 -16,01 5,92 ROE avg Market risk free basis avg 1,18 18,33 -7,03 14,21 10,21 16,55 6,88 14,05 3,52 8,27 12,52 5,83 17,86 6,17 21,14 5,35 9,21 4,27 13,55 4,98 -14,83 5,83 Kruszwica ROE end Market risk free basis end 1998 -10,96 12,59 1999 -73,43 15,83 2000 7,88 17,26 2001 6,09 10,84 2002 7,56 5,69 2003 25,34 5,97 2004 19,47 6,37 2005 13,47 4,32 2006 8,68 4,21 2007 7,36 5,74 2008 23,59 5,92 ROE avg Market risk free basis avg -13,58 18,33 -53,71 14,21 9,13 16,55 6,32 14,05 7,86 8,27 29,01 5,83 21,57 6,17 13,47 5,35 12,09 4,27 7,35 4,98 25,40 5,83 Żywiec ROE end Market risk free basis end 1998 5,10 12,59 1999 6,07 15,83 2000 1,50 17,26 2001 -0,35 10,84 2002 7,02 5,69 2003 18,46 5,97 2004 9,74 6,37 2005 26,51 4,32 2006 35,26 4,21 2007 49,69 5,74 2008 54,32 5,92 ROE avg Market risk free basis avg 8,97 18,33 6,23 14,21 1,60 16,55 -0,39 14,05 3,84 8,27 18,31 5,83 10,27 6,17 26,41 5,35 30,17 4,27 46,31 4,98 50,82 5,83 Wilbo ROE end Market risk free basis end 1998 12,33 12,59 1999 5,33 15,83 2000 6,79 17,26 2001 1,60 10,84 2002 -7,15 5,69 2003 2,93 5,97 2004 -2,13 6,37 2005 -16,30 4,32 2006 2,26 4,21 2007 9,29 5,74 2008 5,53 5,92 ROE avg Market risk free basis avg 13,14 18,33 5,33 14,21 7,03 16,55 1,61 14,05 -7,11 8,27 2,97 5,83 -2,11 6,17 -15,07 5,35 2,28 4,27 9,75 4,98 5,68 5,83 Pepees ROE end Market risk free basis end 1998 9,40 12,59 1999 -2,67 15,83 2000 9,64 17,26 2001 1,78 10,84 2002 0,31 5,69 2003 4,46 5,97 2004 2,80 6,37 2005 -0,24 4,32 2006 1,56 4,21 2007 85,76 5,74 2008 -1,84 5,92 ROE avg Market risk free basis avg 9,73 18,33 -2,64 14,21 10,15 16,55 1,79 14,05 0,31 8,27 4,57 5,83 3,27 6,17 -0,24 5,35 1,67 4,27 71,73 4,98 -1,85 5,83 Food sector average ROE end Market risk free basis end 1998 -1,86 12,59 1999 -13,57 15,83 2000 7,22 17,26 2001 3,93 10,84 2002 3,86 5,69 2003 5,37 5,97 2004 11,87 6,37 2005 9,80 4,32 2006 13,12 4,21 2007 26,95 5,74 2008 10,91 5,92 ROE avg Market risk free basis avg -1,08 18,33 -9,77 14,21 7,81 16,55 4,08 14,05 3,78 8,27 6,61 5,83 13,41 6,17 10,99 5,35 13,89 4,27 25,86 4,98 11,07 5,83 Table 3. The return on equity (ROE) versus the market risk free investment. Source: own calculations. In line with the above conducted calculations to the further calculations as the market risk free investment it was taken the 52 weeks T-bills as presented by the National Bank of Poland. In practical frame the market risk free maximal investment brings the highest possible rate of return. One can say that it is the highest return for the investor without risk and effort from the side of the investor. As the benchmark it is going to be compared with the ROE ratio of the food sector companies listed on the Warsaw Stock Exchange. For the comparisons two parallel calculations are implemented 1. ROE with denominator as at the end of the year and the return of 52 weeks T-bills as at the end of the year.; 2. ROE with denominator as the yearly average of equity and the return of 52 weeks T-bills shown as the yearly average. The aim of this research is to show an economic meaning of an investment in the company as such. The crucial counting lies in the proper return on equity and in this context several questions are ignored: a) possibility to achieve capital gain on the stock exchange, b) the dividend, which in practice during this period was very rarely paid on the Warsaw Stock Exchange. From the point of view of the investor two alternative investments are concerned: 1. In the food sector company listed on the stock exchange with return shown in ROE 2. Market risk free investment assumed in the 52 weeks T-bills. Some purists say that there should be no use of negative ROE because while there is a net loss at the end of the accounting period one cannot count return because there is no return. In mathematical meaning however the negative ROE shows the loss on the capital invested in the company. ROE is a measure of effectiveness of the equity, but not the real return for the investor – as it is in the case of the 52 weeks T-bills – so it measures how effectively the capital given by the shareholders is employed, but not how much earning it gives. Hence it is treated here as the theoretical measure of the return on investment. CONCLUSIONS Characteristic feature is that in the years 1998 – 2001 all food sector companies listed on the WSE has shown the ROE below the market risk free levels. It proves that during these years the investors would have been better of just to buy the alternative market risk free instruments rather than invest in the companies. There are as well companies that almost in all the years show the ROE below the market risk free investment (Pepees, Wilbo, Mieszko). It leads to the conclusion that the shareholders of these companies would have done better if they have had invested in the 52 weeks T-bills instead. The positive feature is that during the period 2003 – 2008 majority of researched companies from food sector listed on the WSE have shown that the managers of these companies were able to use properly the equity available. The food sector is represented on the Warsaw Stock Exchange weaker than it is in the whole Polish economy. This sector is not searched by the financial investors. As the result many companies were withdrawn from the exchange during the listings. The presented research is an attempt to find the answer to the question why the food sector is so little represented on the stock exchange. The indicated low levels of ROE may be one of the crucial reasons. The positive feature is that in recent years the level of ROE is gradually rising. The practice of the Warsaw Stock Exchange was that the dividend was rarely paid off to the investors and the market was a subject to substantial fluctuations so the capital gain was very unstable. The same research tool served as well to indicate that at the end of the researched period the food sector companies that survived on the stock exchange began to show the ROE results much higher than alternative ways of the safe market risk free instruments. REFERENCES 1. Adair T.A. (2006), Corporate Finance Demystified, McGraw-Hill Irwin 2. Bień W. (2008), Zarządzanie finansami przedsiębiorstwa, Difin 3. Bodie Z., Kane A., Marcus A.J. (2009), Investments, McGraw-Hill Irwin 4. Bodie Z., Merton R.C., Cleeton D.L. (2009), Financial Economics, Pearson 5. Bodie Z., Merton R.C. (2003), Finanse, PWE 6. Brealey R.A., Myers P.C., Marcus A.J. (2001), Fundamentals of Corporate Finance, 7. McGraw-Hill University of Phoenix 8. Brealey R.A., Myers P.C. (1999), Podstawy finansów przedsiębiorstw, PWN 9. Brealey R.A., Myers P.C. (2003), Principles of Corporate Finance, McGraw-Hill Irwin 10. Brealey R.A., Myers P.C. (1991), Principles of Corporate Finances, McGraw-Hill Inc 11. Brigham E. F., Daves P.R. (2007), Intermediate Financial Management, Thomson South Western 12. Brigham E. F., Ehrhardt M.C. (2008), Financial Management Theory & Practice, South Western Cengage 13. Brigham E. F., Houston J. (2005), Podstawy zarządzania finansami, PWE 14. Damodaran A. (1996), Investment Valuation, Wiley & Sons 15. Garrison R.H., Noreen E.W., Brewer P.C. (2008), Managerial Accounting, McGraw-Hill 16. Irwin 17. Harrington D.R., Wilson B.D. (1989), Corporate Financial Analysis, DowJones-Irwin 18. Micherda B. red. (2005),, Sprawozdania finansowe i ich analiza, Stow. Ks. w Polsce 19. Pastusiak R. (2009),, Ocena efektywności inwestycji, Cedewu 20. Ross P.A., Westerfield R.W., Jaffe J.F. (1990),, Corporate Finance, McGraw-Hill Irwin 21. Sierpińska M., Jachna T. (1996), Ocena przedsiębiorstwa wg standardów światowych, 22. PWN 23. Siudek T. (2004), Analiza finansowa podmiotów gospodarczych, Wyd. SGGW 24. Wędzki D. (2003), Strategie płynności finansowej przedsiębiorstwa, Of. Ekon.