Thoughts on Starting a Different Conversation with Students about

advertisement

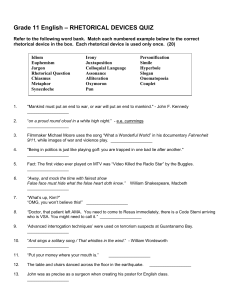

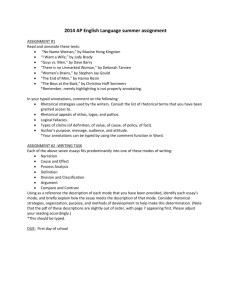

Thoughts on Starting a Different Conversation with Students about Maintaining Academic Integrity Stephanie Roach, University of Michigan-Flint Context The following was presented in session D8: Handouts, Flyers, and Signs: Small Conversations that Make a Big Difference. The aim of each individual presentation in the session was to demonstrate how larger rhetorical and pedagogical problems are addressed through the seemingly utilitarian documents—the handouts, the flyers, the signs—we create in our various roles as writing teachers and writing program administrators. What do these documents say about the classrooms and programs we represent? What disciplinary knowledge is embedded in them? What values do they affirm? What kinds of conversations do they start? Each individual presenter began their presentation by asking the audience to participate in a small activity designed to generate discussion and frame the issue to be presented through a specific handout, flyer, or sign. In this case, a handout on academic integrity was shared along with thoughts on its development and use and the kinds of big conversations with students it might help start about plagiarism as a rhetorical problem, the contested boundaries of plagiarism, the larger context of teacher-readers’ grave responses to plagiarism, the ethos of one’s rhetoric, the significance of revision, and how boundaries between writers and readers are negotiated through rhetorical choice that attends to the rhetorical effect of writing on readers. Conversation Starter Think about the physical or emotional reactions you’ve had when reading something that seems to violate academic integrity (or, for you lucky few, the reactions you think you might have reading something that seems to violate academic integrity). What are two or three words you would use to describe your responses? Whether you hit on the words shared by those attending the session—betrayal, shock, disappointment, anger, opportunity, incredulous, sad—you likely hit on words that point to a visceral, affective, or gut reaction, words that remind us that, no matter the kind of response, readers have a reaction to writing that seems to violate academic integrity. We react because of some message we have received in and between the lines of the text. The page practically screams out to us: “I didn’t learn anything in your class about documentation”; or, “Look here—something is obviously different from the rest”; or, “Hold up—is that right?”. We react and respond to the rhetorical effect of the choices students have made in their writing. Background and Framing Questions For a long time I’ve been fascinated by the variety of reactions (changing and changeable) I have and my colleagues have had to seeing in print something that definitely hits on the spectrum of academic misconduct. What are those first triggers, hints, signs on the page, and why do they seem, when we see them, to be perfectly obvious to us, and yet not at all clear to students—or sort of clear enough that some of the students get what happened this time (or say they do) but don’t know how to revise or stay out of trouble in a future essay or class?1 I’ve even had several students say they were surprised I could see things that turn out to be unquoted passages or way too close to the original paraphrasing, helping to build a reputation that I have some kind of magical, alien quality, or that I really am out to get certain students—both of which unnecessarily muddy and mystify the issue of academic misconduct. I’ve tried talking with students about why the academic community feels so strongly about the concept of academic integrity, how serious the consequences might be, how easy it is for me to find something on Google if they found something on Google. We’ve talked about the types and varieties of plagiarism, what motivates academic misconduct (I believe there are hundreds of serious reasons students might be tempted), and how one might make different choices to overcome even the strongest motivation. I talk about the choices that go into making up a final draft and the very fact that the idea of a final draft is about sending the message that you as the writer are secure enough in all your choices to now stand behind every word and be judged. In other words, I try to be focused on the idea of making choices in writing and revision so that students get in the habit of thinking about how their choices create rhetorical effects, and I try to be upfront about what informs my reading so that students can make more informed rhetorical choices. Ultimately, in line with Diane Pecorari’s claim that plagiarism is “fundamentally a specific kind of language in use” (1), I see maintaining academic integrity as making smart rhetorical choices that send an accurate or at least good faith message to readers about how one text intersects with others. How we construct our sentences and what clues we leave readers send messages not only about the content of a piece of writing but also how readers should read that writing. And what the page says may belie our best intentions. The questions, then, that I’ve been considering: How do I get students to see the messages they are sending? How do I get across that rhetorical devices we use or don’t use such as quotation marks or voice markers have rhetorical effects? How do I start the conversation that essays that avoid academic misconduct aren’t not doing something (like not stealing/cheating), instead they are actively doing something by employing specific writing strategies and sending appropriate messages to readers? The idea of not doing (don’t take others words and ideas) can be easily understood, but the doing required not to violate academic integrity (making choices in one’s writing that tell readers everything they need to know) takes a kind of rhetorical savvy developed by serious practice. The question for me has been how to bring students into the conversation where maintaining academic integrity isn’t about avoiding something obvious (which most students feel they can certainly avoid already), but doing something very subtle (which many students don’t yet see)2. Thus, over the years, I’ve been trying to build better handouts for students that address issues of academic integrity in the context of the messages we send on the page and the fact that things like quotation marks and ellipses—every little choice really—have rhetorical effects. Quotation marks, for example, say to the reader “hey, the ‘I’ you’ve been reading is not speaking anymore,” and smart readers will want to know why, why give up valuable real estate to someone else. Smart writers, then, need to use the quotation mark to be honest about who said what, but more importantly, they need to help readers understand who is speaking in the acknowledged quotation, why they are speaking, and why their words are so important. Good, ethical writing does not result from not doing something, but rather from actively making rhetorical choices that attend to and fulfill the “metatextual” (Pecorari) needs of readers. Invoking Diane Pecorari, Wendy SutherlandSmith reminds us of the “six essential elements of plagiarism” (70): 1) An Object, 2) Which Has Been Taken, 3) From a Particular Source, 4) By an Agent, 5) Without (Adequate) Acknowledgment, 6) And With or Without Intention to Deceive (70-72). What we put on the page helps mark the object, the source, our intended use as an agent, and how we mean others to view this piece of text. I’ve been trying to design handouts that help students come at the issue of academic integrity from this perspective of rhetorical choices and rhetorical effects so they see plagiarism as a rhetorical problem in the writing instead of something they can avoid outside the writing by simply knowing the definition of plagiarism or being a good person. The Handouts The handouts I’ve built oversimplify of course, yet they help me frame the discussion of academic integrity in a new way and help the class get their hands into real language uses. The materials I shared at the conference cannot be fully reproduced here, but I can describe their structure and function. In one handout I describe and illustrate three basic kinds of sentences we use to signal our own contributions and the contributions of others: the sentence that does not use quotation marks or include an in-text citation, the sentence that does not include quotation marks but does include an in-text citation, and the sentence that includes quotation marks and an in-text citation. The handout draws these types of sentences out in words, and in class, I illustrate the sentences visually with long lines, quotation marks, and/or parenthesis. An example from the handout: This kind of sentence without quotation marks but with an in-text citation and often a voice marker that introduces or references another person or author tells the reader that I am using my words and my way of writing to describe or investigate the ideas of someone else (intext citation). Visually this could be represented as: _________________________( ). The handout also includes direct information for students such as a note about the sentence type (example: when quoting others, using quotation marks around word for word passages and including an in-text citation helps you avoid academic misconduct, but good writing will do more than that), a tip for crafting this kind of sentence, and an example. The back of the handout then describes and illustrates three kinds of misconduct: failing to signal the contributions of others by taking words, taking syntax, or taking ideas. Under each type of misconduct sections from student essays are printed with permission as well as original passages from a source contributing to the student’s work. The handout describes for students the kind of rhetorical problem encountered in the student sample (example: The sentence tells the reader that these words and this way of writing belong to the student. However, the entire passage is essentially a direct word for word quotation. The student has used the source’s words but has not told the reader). Ultimately the handout asks students to help work out solutions to the rhetorical problems presented in the passages. A second handout then asks students to get more directly involved in revision. An introductory paragraph to a student essay is printed with permission and an original passage from the website used by the writer is included. Students are asked to look for the clues the writer is sending to readers about what is his and what belongs to others and to make suggestions for other rhetorical choices this writer could make in revising and strengthening his introduction. Early Results Of all the conversations I can start with students using these handouts, my favorite is the focus on head to toe revision. I’ve been pleased with the way students get into the material and how more students sit up and take notice during the conversation (rather than tuning out what they think they already know). Those who have, say, plagiarized by thesaurus see the risky messages they’ve been sending. In focusing on rhetorical choices, not just rules of conduct, students come to ask better questions about academic integrity and engage in better conversations about how writing works and why. I’ve also noticed fewer academic integrity violations in my sections and certainly far less surprise and confusion when I do have to address an instance of misconduct. Ultimately, the handouts help completely reframe an important issue and allow me to draw on a significant and rich disciplinary discussion. Notes 1. I agree with Wendy Sutherland-Smith that students have trouble with plagiarism in “operational” not definitional terms (155); see also her concerns about repeat offenders (2). 2. Pecorari has an excellent discussion that illuminates not only the subtleties but the vast complexities of citation (see especially chapters 3 and 4). Works Cited Pecorari, Diane. Academic Writing and Plagiarism: A Linguistic Analysis. New York: Continuum, 2008. Print. Sutherland-Smith, Wendy. Plagiarism, the Internet, and Student Learning: Improving Academic Integrity. New York: Routledge, 2008. Print.