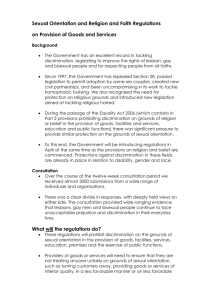

1 - NISRA

advertisement