1 - Kaplan Financial

advertisement

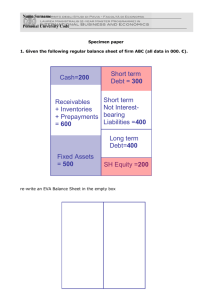

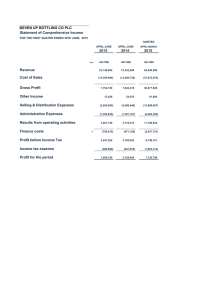

4 THE STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION 4.1 Introduction We have already covered, you’ll be glad to know, the essence of the statement of financial position. In paragraph 1.2 it was defined as ‘a statement of the final positions of a business at a given date’. But if you think about it, that is exactly what Percy’s accounting equation has been doing, each time we prepared it. The statement of financial position is the accounting equation, only set out in vertical form in order to be more readily understood. In real life of course, we don’t prepare the statement of financial position (or even an accounting equation) every time a business makes a transaction, as we have been doing up to now. The statement of financial position is prepared at the end of a period, as we said in Chapter 1, and the books of account, or accounting records, are kept to record individual transactions as they happen. We will look at these in detail in Chapter 6, after we have seen what the end products (the statement of financial position and income statement) look like. 4.2 Layout of the statement of financial position We will set out Percy Pilbeam’s final accounting equation as a formal statement of financial position, and then explain each section in turn. 15 P PILBEAM Statement of financial position at 31 January 20X1 £ ASSETS Non-current assets Motor vehicles Current assets Inventories Trade receivables Cash £ 4,000 2,000 6,300 ________ 8,300 ________ Total assets CAPITAL AND LIABILITIES Capital As at 1 January Profit for the period Less drawings At 31 January 12,300 10,000 800 (500) 10,300 Non-current liabilities Current liabilities Trade payables 2000 ________ 2000 ________ Total capital and liabilities 12,300 ______ Some headings have been shown for illustration: in practice, if there were, for example, no receivables, this heading would be left out. 4.3 Non-current assets and current assets An asset was defined in paragraph 2.4 as something owned by a business, available for use in the business. As you can see from Percy’s statement of financial position, there is a distinction between noncurrent assets and current assets. Non-current assets can be defined as ‘assets acquired for use within a business over several years, with a view to earning profits, but not for resale’. Current assets are ‘assets acquired for conversion into cash in the ordinary course of business’. In other words, non-current assets are those which a business keeps and uses in the long term, and current assets are those which pass through the business as part of the normal trading process. 16 4.4 Non-current assets Without looking at the answer, try to think of some types of assets which a business would be likely to keep over several years. Target about 10. ………………………………………………. …………………………………………. ………………………………………………. …………………………………………. ………………………………………………. …………………………………………. ………………………………………………. …………………………………………. ………………………………………………. …………………………………………… Answer: Land, buildings, plant and machinery, patents, motor vehicles, tools, fixtures and fittings, office equipment, computers, long-term investments, ships, works of art, locomotives. A business will either pay cash or incur a liability when it buys any of these; but as we saw in the example in Chapter 3 the same thing happens when it incurs an expense, such as an electricity bill. We need to distinguish one type of payment from the other. Taking the electricity bill first, this could not in any sense be called an asset. It is simply an expense, to be charged against profit, and as such we call it a revenue expense. We will look at this in Chapter 5. Buying a non-current asset, on the other hand, is called a capital expense. We don’t simply deduct its cost from profit; we show it in the statement of financial position as an asset. But at what value do we show it? 4.5 Depreciation Leaving Percy Pilbeam’s van in the statement of financial position at the amount it cost doesn’t take account of the fact that vans are not immortal. Four years of carrying fruit and vegetables around will probably be enough; and four years is the period which many businesses choose as an ‘estimated useful life’ for motor cars, vans and lorries. Other types of non-current asset will last for different periods; a business might choose, for example, 10 years for plant and machinery and 20 years for furniture. What all this is leading to is that it can’t be correct to have a non-current asset in the statement of financial position at the amount which it cost all through its life. Can you remember the cost of Percy’s van? Cost £4,000. 17 It isn’t worth this amount, in terms of either physical condition or market value, when it is, say, three years old, is it? So what we do is to deduct from profit, or write off, a proportion of the cost of the van for each of its estimated useful life. There are various ways of doing this; the simplest is to write off an equal proportion each year. This exercise is called depreciation, and for Percy’s van it works as follows: £ 4,000 (1,000) Cost Year 1 Depreciation 25% on cost ________ 3,000* (1,000) Year 2 Depreciation ________ 2,000* (1,000) Year 3 Depreciation ________ 1,000* (1,000) Year 4 Depreciation ________ ________ The amounts marked with an * are the amounts left at the end of each year after the charge has been made for depreciation, and are called the carrying amount (or written-down value). Depreciation, like everything else in accounting, has its dual effect. (a) Reduction in non-current asset value. (b) Reduction in profit Each year the charge for depreciation is deducted from profit, but in the statement of financial position these charges accumulate, and at the end of, for example, the third year of Percy’s ownership of the van his statement of financial position would start off how? Cost Non-current assets Motor vehicles 4,000 Accumulated Carrying Depreciation amount at at end of year end of year 3,000 1,000 And how much is charged against profit, as an expense, each year? £1,000. In summary we are spreading the cost of the van over its useful life to the business eg. 4 years. 4.6 Current assets In Chapter 4.3 we defined current assets as ‘assets acquired for conversion into cash in the ordinary course of business’. We also said that current assets are those which pass through the business as part of the normal trading process. 18 Just as people or animals cannot live without blood constantly moving through their bodies, so a business cannot exist without the constant movement of current assets. The three types of current assets shown in Percy Pilbeam’s statement of financial position in paragraph 4.2 were: (a) Inventories (b) Receivables (c) Cash Assuming that Percy, once he gets started, makes most of his sales for credit, the ‘movement’ that we are talking about will happen as follows: (a) Assuming that Percy’s business has some cash in the bank, he will normally use most of it to buy inventories. (b) If he sells his inventories for credit, he will have receivables. (c) When the receivables pay, as he hopes they will, he will have cash. And so it goes on. Obviously, some of his cash will go elsewhere (expenses, drawings, etc), some of his inventories may not be sold, and some of his receivables may not pay. But the majority of cash, inventories and receivables will flow in this way. We will now look at each of these current assets in a little more detail, taking them in the order (inventories, receivables, cash) in which by convention they appear in the statement of financial position. 4.7 Inventories In Percy Pilbeam’s business it is fairly obvious what his inventories consists of. What is it? Fruit and vegetables. For a retailer such as Percy, the inventories held at a given time are simply the goods which he has available for sale. However, other businesses manufacture their inventories, and in their statement of financial position ‘inventories’ will include not only finished goods, but also raw materials and components. Also included in a manufacturing business are goods which at the statement of financial position date are in the process of being manufactured. These are known as work in progress. To arrive at the physical quantity of inventories at the statement of financial position date, Percy must of course count it, ie. carry out a stock-taking. But at what value should he show it in the statement of financial position? The price it cost him, or the price he charges? The conventional rule here is that inventories are valued at the lower of cost and net realisable value. This means that a business should normally value its inventories at cost price, unless it can’t sell it at a profit. If it can only sell an item of inventory for less than it cost, it should reduce the value of that item to the lower, selling value. ‘Net realisable value’ means selling price less any further costs to be incurred before the item can be sold. Finding out how ‘cost’ is calculated will take up quite a large proportion of your time later on. For the moment, it is enough to say that ‘cost’ includes not only the cost of buying goods but, in a manufacturing industry, the costs of manufacture too, ie. labour and some production 19 expenses. In fact, it includes all costs incurred by a business in bringing inventories and work in progress to its present location and condition. 4.8 Receivables Clearly, receivables are people who owe money to the business, and the amount at which they are shown in the statement of financial position should be the total of these receivables. Inevitably, if a business makes sales on credit, it will sometimes have receivables that are slow to pay, or argue about the amount owed, or even go bust. In such cases we have to take account of this, and make an allowance against receivables. If we didn’t, we would be overstating our assets by valuing receivables at a greater amount than they are likely to pay. What do you think the dual effect is of such an allowance? (If you don’t know don’t look at the answer yet: look back at paragraph 4.5 and see if you can spot the similarity). 4.9 (a) Reduction in receivables. (b) Reduction in profit. Cash No provisions against this either you’ve got it or you haven’t. There are in fact two categories of cash: (a) cash at bank; (b) cash in hand, or petty cash. With cash at bank, remember that the amount on the business’s bank statement won’t always be the same as the amount shown in the statement of financial position. This is because there will usually be cash and cheques, both received and paid, which haven’t yet been processed by the bank. It can take a few days for transactions to go through the system; the result of this is that a bank reconciliation has to be done, adjusting the amount on the bank statement for such items, and also serving the purpose of making sure that the business’s own cash records are correct and up to date. Every business needs a certain amount of petty cash (notes and coins) on the premises to pay for casual expenses such as coffee, biscuits and newspapers. Although the amount held will be small, it is still an asset and has to be shown in the statement of financial position. 4.10 Current liabilities In paragraph 2.4 we defined a liability as an amount owed by the business, ie. an obligation to pay money at some future date. A current liability is simply a short-term liability ie. an amount owed by the business, payable within one year. The commonest examples of current liabilities are: (a) trade payables; (b) accrued charges; (c) bank overdraft. 20 4.11 Trade payables These are suppliers of goods, such as Percy Pilbeam’s wholesaler, from whom the business is buying items directly for resale, and whom it isn’t paying immediately. Many businesses give one month’s credit, and many more take longer than that. 4.12 Accrued charges (Accruals/Prepayments) Accrued charges include services such as rent, electricity, gas and telephone which a trader may have used but not yet paid for. Sometimes it will be an exact bill outstanding, sometimes the bill will not be due yet; but we will have to estimate how much, say, electricity has been used up to and including the date of the statement of financial position. Charges like this tend to be paid in arrears (live now, pay later). We refer to the outstanding amount for the service used as an accrual. An accrual is shown within current liabilities. However sometimes a business may have to pay for a service in advance eg. rent or rates. Instead of the amount being a liability as we’ve not yet used the service, it’s a current asset known as a prepayment. If during his first month’s trading, Percy had paid 3 months rent, he would have paid 2 months in advance. This 2 months of rent would be an example of a prepayment and should be shown alongside receivables in the statement of financial position. 4.13 Bank overdraft If you owe money to the bank (you have an overdraft), the bank actually has an asset (receivable) in its own books; this may not be very convincing as an argument next time you try to negotiate an overdraft. Conversely, if you have cash in the bank (ie. a positive balance) the bank owes you money, which you can, and doubtless will, withdraw. Don’t get confused by this: you will be writing up only one business’s books at a time. 4.14 Non-current liabilities These are amounts owed by the business, payable more than one year after the date of the statement of financial position. Long-term loans are much the commonest example. 4.15 Format of the Statement of financial position Previously we looked at the accounting equation: Net assets = Capital; or Assets – Liabilities = Capital Now we have simply rearranged the equation to show: 21 Assets = Capital + Liabilities 4.16 Revision questions (1) Define non-current assets. (2) Define current assets. (3) Are the following non-current or current assets? (a) Buildings (b) Receivables (c) Petty cash (d) Fixtures & fittings (e) Work in progress (f) Long-term investments (4) Is the purchase of a non-current asset called a capital or a revenue expense? (5) (a) If a van cost £5,000 and is written off in equal proportions over four years, how much depreciation should be charged against profit each year? (b) At what value should the van be shown in the statement of financial position at the end of the third year? (6) What is the dual effect of charging depreciation? (a) (b) (7) Name three types of inventories which you might expect to find in a manufacturing business: (a) (b) (c) (8) What is the conventional rule on the valuation of inventories? (9) Define a current liability? (10) Name three types of current liability. (a) (b) (c) 22 Answers (1) Fixed assets are assets bought by the business for use over a number of years, with the aim of earning profits, but not for resale. (2) Current assets are assets acquired for conversion into cash in the ordinary course of business. (3) (a) (b) (c) (d) (e) (f) (4) Capital (5) (a) £5,000 ÷ 4 = £1,250 (cost ÷ useful life = depreciation per annum) (b) £5,000 (3 x 1,250) = £1,250 (cost accumulated depreciation) (6) (a) (b) Reduction in profit Reduction in value of fixed asset (7) (a) (b) (c) (d) Raw materials Components Finished goods Work in progress (8) Inventories should be valued at the lower of cost and net realisable value. (9) A current liability is an amount owed by the business which is payable within one year. (10) (a) (b) (c) fixed current current fixed current fixed Trade payables Accruals Bank overdraft 23