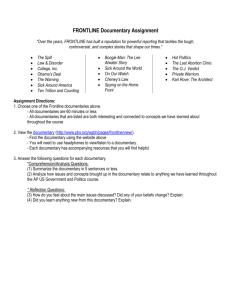

JLS 106 - nau.edu - Northern Arizona University

advertisement

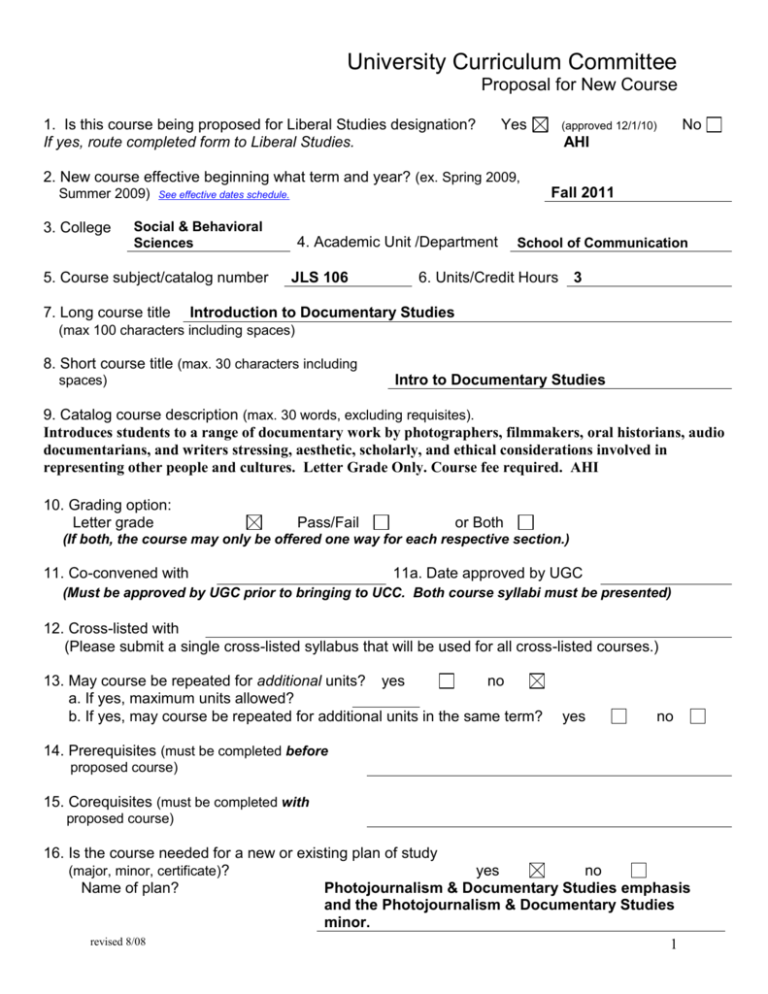

University Curriculum Committee Proposal for New Course 1. Is this course being proposed for Liberal Studies designation? If yes, route completed form to Liberal Studies. Yes (approved 12/1/10) No AHI 2. New course effective beginning what term and year? (ex. Spring 2009, Summer 2009) 3. College Fall 2011 See effective dates schedule. Social & Behavioral Sciences 5. Course subject/catalog number 7. Long course title 4. Academic Unit /Department JLS 106 School of Communication 6. Units/Credit Hours 3 Introduction to Documentary Studies (max 100 characters including spaces) 8. Short course title (max. 30 characters including Intro to Documentary Studies spaces) 9. Catalog course description (max. 30 words, excluding requisites). Introduces students to a range of documentary work by photographers, filmmakers, oral historians, audio documentarians, and writers stressing, aesthetic, scholarly, and ethical considerations involved in representing other people and cultures. Letter Grade Only. Course fee required. AHI 10. Grading option: Letter grade Pass/Fail or Both (If both, the course may only be offered one way for each respective section.) 11. Co-convened with 11a. Date approved by UGC (Must be approved by UGC prior to bringing to UCC. Both course syllabi must be presented) 12. Cross-listed with (Please submit a single cross-listed syllabus that will be used for all cross-listed courses.) 13. May course be repeated for additional units? yes no a. If yes, maximum units allowed? b. If yes, may course be repeated for additional units in the same term? yes no 14. Prerequisites (must be completed before proposed course) 15. Corequisites (must be completed with proposed course) 16. Is the course needed for a new or existing plan of study (major, minor, certificate)? yes no Name of plan? Photojournalism & Documentary Studies emphasis and the Photojournalism & Documentary Studies minor. revised 8/08 1 Note: If required, a new plan or plan change form must be submitted with this request. 17. Is a potential equivalent course offered at a community college (lower division only) If yes, does it require listing in the Course Equivalency Guide? Please list, if known, the institution and subject/catalog number of the course yes yes no no 18. Names of current faculty qualified to teach this course: Mark Neumann, Laura Camden, Kurt Lancaster, Peter Frederici 19. Justification for new course, including unique features if applicable. (Attach proposed syllabus in the approved university format). This new introductory course offers students an opportunity to explore diverse approaches to documentary work in video/film, audio, multimedia, photography, nonfiction writing, and journalism. It combines a solid grounding in the academic and theoretical literature of documentary media. For Official AIO Use Only: Component Type Consent Topics Course 35. Approvals Department Chair (if appropriate) Date Chair of college curriculum committee Date Dean of college Date For Committees use only For University Curriculum Committee Date Action taken: Approved as submitted revised 8/08 Approved as modified 2 General Information College of Social & Behavioral Sciences, School of Communication JLS 106 Introduction to Documentary Studies Semesters offered: Fall, Spring (1st offered Fall 2011) T/Th 12:45-2:00pm, 3 credit hours Instructor: Rotating Photojournalism and Documentary Studies faculty (Laura Camden, Peter Friederici, Kurt Lancaster, Mark Neumann) Office: 301 School of Communication, Bldg. 16 Office Hours: T/Th 11-1 Course Prerequisites: None Course Description This course focuses on a partial survey and exploration of documentary techniques, styles and practices. It is a foundational course for students pursuing the photojournalism and documentary studies track in the Journalism major, and it is open to all students with an interest in learning more about documentary studies. Documentaries are representations of real issues, places, situations, events, communities, and individuals that are treated with an aesthetic and narrative sensibility. Documentaries provide us with compelling narratives made of words, images, and sounds that strive to enlarge and sometimes transform our understanding of social, cultural, political, and economic worlds people move through. This course asks students to examine documentary traditions and develop basic skills for working in documentary forms. This course supports the mission of the Liberal Studies Program by examining the broad range of knowledge that have shaped not only the documentary form, but the subjects they cover—from the oral histories of the human condition examined by documentarians over history to contemporary multimedia forms documenting human injustices. By engaging in the understanding and practice of the written, oral, image, and motion picture forms in examining how people live their lives in the world—and the social forces shaping that lived process—students gain a deeper understanding how different groups of people from around the world live in times of dramatic change as a way of understanding not only others, but themselves (a powerful skill for professional life and success beyond the confines of this course). The documentary form examines the traditions and legacies of others in order to discover the dynamics and tensions of how different people live, the environments they’re in, and from that study, the beginnings of how human values are lived universally through the specificity of documenting a subject. In short, an examination of the potentials of how others live and contribute their lives in society and by extension through the documentary form, a way in how they can potentially contribute to society and live in the world. JLS 106 Introduction to Documentary Studies falls within the Aesthetic and Humanistic Inquiry block of liberal studies by engaging such elements as: Studying the human condition through philosophical inquiry and analysis of a variety of documentaries. The relationship between context of how people live their lives as documented through the creative expression of the documentarian. Explores the major conceptual frameworks of documentaries by making sense of such creative arts elements as narrative structure, photography, storytelling, audio narratives, and filmmaking. Examines the lived human experience and values as expressed through creative endeavors of the documentary form. Students will also develop their capacities for analysis and ethical reasoning by examining how the documentary form began and how it evolved, including a critical analysis of specific documentary works and the ethical stance of the documentarian. By doing so, students will gain an understanding of the multiple facets of the human condition by not only examining key historical documentary works, but by also creating a documentary by choosing a subject and examining that subject’s human condition. Liberal Studies Essential Skills The reading, viewing, listening material in this course, as well as course lectures and discussions, will foster critical thinking skills through an examination of the documentary form as a basis for constructing knowledge claims through evidence. This course considers, in part, the traditions of documentary as well as their current manifestations. By considering how various documentaries are constructed, this course will provide students with a revised 8/08 3 basis for not only making their own documentary projects; it will also give them the skills for understanding the narrative and evidentiary construction of documentaries they will experience throughout their lives. In short, they will understand how documentaries are put together as constructions of knowledge and information that inherently contain perspectives and viewpoints aimed toward social understanding and possible social action—an essential skill for being a critical consumer of information in their professional success and life beyond graduation. Student Learning Expectations/Outcomes for this Course Over the course of this semester, students will gain a deep appreciation of the documentary form not only as a vital form of human creative expression, but they will gain a context on how human lives are documented in that artistic form. Furthermore, to help foster the spirit of critical thinking, it is expected that students will do all the readings, examine all the example of different documentary projects, and participate in lively discussions about the documentary form as a tool of human endeavor and documentation of lived experiences. Finally, to cap off the course learning objectives, students will take the knowledge they have gained from the critical inquiry of key texts and documents, and craft a short documentary project. By actively participating in all of the course requirements, students will: a) Gain knowledge and understanding of the foundations, practices, and transforming nature of documentary work. b) Examine the various techniques and styles of documentary work and how such work conveys meaning to an intended audience. c) Explore the motives and problems confronting documentarians—especially as it relates to articulating the meaning of documentary argument and premises and determining how the conclusions of the documentary were created by the evidence provided. d) Explore the archival resources available to documentary production, including recognizing the biases of the documentarian in utilizing archival resources. This will include examining the validity of archival sources, taking into account the contextual factors of the archival source and how it’s being used as evidence in the documentary’s conceptual scheme. e) Evaluate the possibilities and limitations associated with articulating the meaning of a particular medium for doing documentary work—and how different media require different types of evidence in crafting an argument and drawing conclusions. f) Survey a range of documentary works that can serve as models for developing original documentary projects—examining them for the key elements of critical thinking: articulating the meaning of the film, judging the truth of the subject’s position (and taking into account the documentarian’s biases), and determining whether or not the conclusion is warranted from the evidence provided in the film. g) Engage the basic practices for producing a documentary project, which must articulate the central meaning of the subject, and through the documentary evidence judge the veracity of the subject’s position (keeping in mind your own biases), and draw a conclusion from the documentary evidence. Assessment and Methods of Assessment of Student Learning Outcomes QUIZZES-Students in this course are required to complete 8 quizzes. Each quiz will be based on the reading and lecture material for each of the topic areas in the course outline. The quizzes will be taken on-line, available during a designated time period following the completion of each topic section. Each quiz is worth 15 points. Total for all 8 quizzes: 120 points EXAMS- There will be two exams during this course, a mid-term exam and a final exam. The exams will be essay exams that will be conducted as open-book, open note take-home exams. The midterm exam will focus on topic sections I-IV on the course outline, and will be comprised of 4 essay questions that focus on the material in those topic sections. In addition, the midterm exam will include questions that require an application of theoretical and critical concepts from this course. This portion of the exam will help to determine how well students can exercise their critical thinking skills in analyzing a documentary text. The final exam will focus on topic sections V-IX on the course outline, and will be comprised of 4 essay questions that focus on the material in those topics. The final exam will also include questions that require an application of theoretical and critical concepts. This portion of the final exam will help to determine how well students can exercise their critical thinking skills in analyzing a documentary text. Each exam will be submitted as typed, double-spaced, using a 12-point font with 1” margins. The approximate page-length for each exam will be 8-10 pages. Each exam will be worth 100 points. Total for mid-term and final exam: 200 points GROUP DOCUMENTARY PROJECTS-Students in this course will be responsible for doing one group documentary project (groups will be comprised of 3-4 students) on a subject of their choosing that meets instructor approval. The documentary project will engage the key elements of the critical thinking skills by engaging the meaning of their documentary to an audience and how they will provide evidence in conveying their meaning. These revised 8/08 4 projects will be completed throughout the semester in a series of stages. These stages entail: 1) 2) 3) 4) the submission of a proposal at the start of the 3rd week of classes (10 points), four bi-weekly progress reports after proposal is approved (5 points each-20 points total), a class presentation (10 points), and the submission of the final project (60 points). Each student in a group will receive the same grade for each stage and final submission of the project. The total earned for the group project: 100 points Grading System Through quizzes, exams, and the final group project, students can earn a total of 420 points in this course. The final grade for the course will be determined according to the following scale: 420-378 points= A 377-336 points= B 335-294 points= C 293-252 points= D Below 251 points= F Course structure/approach/outline I. Introduction The initial week of this course will be devoted to discussing the general nature of documentary work and why it is worthy of further study. In addition, we will consider the possibilities for developing group efforts that allow students to engage in creating a semester-long documentary project. Reading: Robert Coles, Doing Documentary Work, introduction and Chapter 1. Listening (in class): Ira Glass, “Watching the Detectives” II. Documentary Traditions: Reformist Roots and the Pursuit of “Human Actuality” This section of the course will consider some of the 19th century roots of documentary work in reform movements, as well as the implicit dimensions of observational recording of society, the politics and ethics of observation and representation of social life. Reading: Coles, Doing Documentary Work, chapter 3 “The Tradition: Fact and Fiction;” Henry Mayhew, excerpt from London Labour and the London Poor (VISTA) Jacob Riis, excerpt from How the Other Half Lives (VISTA and on-line) http://xroads.virginia.edu/%7Ema01/davis/photography/images/riisphotos/slideshow1.html Following section II, you will take Quiz #1 (on-line) III. Discovering the Archives This section of the course considers the wide range of material that is available to documentarians via libraries, special collections, museums, and Internet resources. In particular, we will focus on ways to use the available material, and how we can discover material that help formulate the basis for documentary projects. Class will visit NAU’s Cline Library for tour of their special collections. Review for class lecture and discussion: The Jazz Loft Project (listen to 10 episode radio series-online) http://www.jazzloftproject.org/?s=radio The Library of Congress: American Memory http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/index.html The Internet Archive http://www.archive.org/ Northeast Historic Film http://www.oldfilm.org/ Following section III, you will take Quiz #2 (on-line) IV. Multimedia Documentary/Curated Exhibitions/New (old) Documentary Approaches This section of the course examines the expansive range of possibilities for the presentation of documentary work. From the use of graphic novels and illustrations mixed with real-life experience, to the use of archival and found materials, to the creation of documentary-based audio tours, we will explore how various documentary efforts have been experimenting with new and exciting forms of presenting information. revised 8/08 5 David Greenberger, excerpts from Duplex Planet (VISTA) Art Spieglman, excerpts from Maus I: A Survivor’s Tale: My Father Bleeds History (VISTA) Soundwalks http://www.soundwalk.com/#/TOURS/ http://www.nytimes.com/ref/arts/tour-instructions.html The Hidden World of Girls http://www.kitchensisters.org/girlstories/ Square America http://www.squareamerica.com/ The Dead Media Project http://student.vfs.com/~deadmedia/frame.html Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America http://withoutsanctuary.org/ Following section IV, you will take Quiz #3 (on-line) Mid-Term Exam (Take-home Essay Exam) You will have one week to complete this essay exam. The exam will be distributed in class. It is a take-home exam so you can consult course materials. The exam will be based on course lectures and syllabus materials covered in sections I-IV. V. New Journalism, Literary Journalism and Techniques for Telling Stories The roots of literary journalism and the “new journalism” extend all the way back to the work of 19 th century writers like Henry Mayhew. In different ways, examples of documentary-based journalism have been with us throughout the 20th century. In this section we’ll explore a few of the writers that initiated what was called the “new journalism” in the 1960s, and later became referred to as literary journalism. Their techniques for finding stories and writing about people, places and events in compelling ways is foundational in many forms of doing documentary work. Reading: Mark Kramer and Wendy Call, Telling True Stories, Part I, II, III. Gay Talese, “Of Things Unnoticed” and “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold” (VISTA) Joseph Mitchell, “The Bottom of the Harbor” (VISTA) Susan Orlean, “Lifelike” (VISTA) Ted Conover, excerpt from Coyotes (VISTA) Dave Eggers, “Hitchhiker’s Cuba” (VISTA) Following section V, you will take Quiz #4 (on-line) VI. Self-Reports and Oral History For documentarians and historians, oral history interviews are valuable as sources of new knowledge about the past and as new interpretive perspectives on it. Interviews have especially enriched the work of a generation of documentarians, providing information about everyday life and insights into the mentalities of what are sometimes termed "ordinary people" that are simply unavailable from more traditional sources. In addition, the techniques and uses of oral history accounts are crucial in many dimensions of producing documentary work. This section focuses on some of the fundamental skills and uses of oral history and self-reports that can be applied to documentary practice. Reading: Linda Shopes, “Making Sense of Oral History” (online) http://historymatters.gmu.edu/mse/oral/ Judith Moyer, “Step By Step Guide to Oral History”(online) http://dohistory.org/on_your_own/toolkit/oralHistory.html#DOIT Studs Terkel, excerpts from American Dreams: Lost and Found (VISTA) Listen: Sample some of the stories from the Story Corps project: http://storycorps.org/listen Following section VI, you will take Quiz #5 (on-line) VII. Creating Stories with Sound In this section, we focus on the use of sound to create distinctive forms of documentary. Audio documentary can draw from a wide range of sonic recordings that can be both generated by a producer (as in the covering of an event and interviews with individuals), as well found recordings in archives and special collections. In this section, we consider how audio documentaries create and re-create self-contained sonic representations of places and people, and some of the techniques producers use for doing such work. Reading: Charles Hardy, “Authoring in Sound” (VISTA) revised 8/08 6 Listen: Tony Schwartz “Nueva York: A Tape of Puerto Rican New Yorkers” –in class listening “Tony Schwartz: 30,000 Recordings Later” by The Kitchen Sisters (Nikki Silva and Davia Nelson) (NPR’s Lost and Found Sound)—in class listening Listen in preparation for class discussion: “Ghetto Life 101” by LeAlan Jones, Lloyd Newman, David Isay (Sound Portraits) http://soundportraits.org/on-air/ghetto_life_101/ “The Sunshine Hotel” by David Isay (Sound Portraits) http://www.soundportraits.org/on-air/the_sunshine_hotel/ The Sonic Memorial Project, The Kitchen Sisters (and others) http://www.sonicmemorial.org/sonic/public/index.html Following section VII, you will take Quiz #6 (on-line) VIII. Documentary Images I: Photography As we have seen in earlier sections, documentary photography emerges from the practices of professional photographers, photojournalists, and even the images made by amateur photographers that become incorporated in formal documentary projects. An entire course could be taught about documentary photography. In this section, however, we will conduct a brief survey of some of the issues surrounding documentary photographs. How do we analyze such images? What are the ethics associated with making images? And what can we learn from different examples of documentary photography? Reading: Derrick Price, “Surveyors and Surveyed: Photography Out and About,” (VISTA) Thomas Kavanaugh, “Reading Historic Photographs” (VISTA and online) http://php.indiana.edu/%7Etkavanag/phothana.html James Curtis, “Making Sense of Documentary Photography” (online) http://historymatters.gmu.edu/mse/photos/ Frank Goodyear, “Analyze A Daguerreotype” (online) http://historymatters.gmu.edu/mse/sia/photo.htm Grazia Neri, “Ethics and Photography” (VISTA) View: Photographs of Dorthea Lange: http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/fsahtml/fachap03.html Photographs of Walker Evans:http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/fsahtml/fachap04.html Robert Frank, The Americans (in-class viewing) Alex Harris, Red, White, Blue and God Loves You (in class viewing) Following section VIII, you will take Quiz #7 (on-line) IX. Documentary Images II: Moving Images Creating a list of documentary films that claims to be comprehensive would take up the content of several university courses. In this section, we can only scratch the surface and discuss some examples of films that allow us insight into the techniques of telling stories about real life using film. Here, we focus on an overview of the different subgenres of documentary film and explore several examples that provide us with lessons about how different documentary filmmakers have approached a variety of subjects with different story-telling techniques. Reading: Pat Aufderheide, Documentary Film: A Very Short Introduction Liz Stubbs, selected interviews from Documentary Filmmakers Speak Viewing (all in class viewing): Robert Flaherty, Nanook of the North Barbara Koppel, Harlan County, USA (excerpted selection) Ken Burns, The Civil War (excerpted selection) Alan Berliner, The Sweetest Sound Stacy Peralta, Dogtown and Z-Boys (excerpted selection) Following section IX, you will take Quiz #8 (on-line) X. Class Presentation of Documentary Group Projects Each group will have 15-20 minutes to present their semester project to the rest of the class. These presentations should include an overview of how the project originated, how the group determined a particular narrative and revised 8/08 7 stylistic form for their project, and a discussion of the problems they encountered and the lessons learned along the way in producing their work. XI. Final Exam (Take-home essay exam) You will have approximately one week to complete this essay exam. The exam will be distributed in class at the end of the presentations of the group documentary projects. It is a take-home exam so you can consult course materials. The exam will be based on course lectures and syllabus materials covered in sections V-IX. The exam will be due during the scheduled meeting time for the final exam in this class. Textbook and required materials Robert Coles, Doing Documentary Work (Oxford University Press, 1998) Patricia Aufderheide, Documentary Film: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2007) Mark Kramer/Wendy Call (eds.) Telling True Stories (Penguin 2007) Additional required course readings, videos, audio recordings, and websites will be posted on the class website (VISTA), available on-line or distributed in class meetings. Please consult course outline. Course policy Retests/makeup tests/missed deadlines Considering that the midterm and final exams are take-home exams, and the quizzes are taken on-line during a designated time period for each quiz, there are no opportunities to miss an exam or quiz due to absence from class. Therefore, there will be no need to schedule a make-up for an exam or quiz. All work must be submitted on time. The due dates for each exam, quiz, and presentation are scheduled on the course syllabus. Work that is not submitted on time will not be accepted. Attendance Students engaged in a university education are responsible for their own affairs. You will need to come to class regularly in order to benefit from lecture material and participate in class discussions. If you do not attend class regularly, it is unlikely you will pass this class. You will NOT receive points for attending and participating in class. This is just something you should do for your own benefit and to contribute to the diversity of viewpoints in a classroom setting. If you are an athlete, you should have the courtesy to advise me of not attending class due to an absence from campus due to a competition. I reserve the right to administratively drop students who do not attend class during the first week so I can give that space to a student who wants to take the class. If you do not attend a class, you are required to get the material you missed from another classmate. I will not be reproducing content delivered in class for students who do not attend class. Plagiarism and Academic Dishonesty: You must do original work. If you are stealing someone else’s work (from any source—internet, student, publications), you will fail that assignment or exam with a grade of 0 (zero) points. In addition, you will have your case of academic dishonesty reported to the university administration. More than one occurrence of academic dishonesty or plagiarism in this course will result in a failing grade for this course. In addition, you cannot duplicate work used in another class. All work done in this course must be original and not created in another course. For more on academic dishonesty and plagiarism, please consult, Appendix G of the NAU Student Handbook: http://www4.nau.edu/stulife/handbookdishonesty.htm. NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIVERSITY POLICY STATEMENTS SAFE ENVIRONMENT POLICY NAU’s Safe Working and Learning Environment Policy seeks to prohibit discrimination and promote the safety of all individuals within the university. The goal of this policy is to prevent the occurrence of discrimination on the basis of sex, race, color, age, national origin, religion, sexual orientation, disability, or veteran status and to prevent sexual harassment, sexual assault or retaliation by anyone at this university. You may obtain a copy of this policy from the college dean’s office or from the NAU’s Affirmative Action website http://home.nau.edu/diversity/. If you have concerns about this policy, it is important that you contact the departmental chair, dean’s office, the Office of Student Life (928-523-5181), or NAU’s Office of Affirmative Action (928-523-3312). revised 8/08 8 STUDENTS WITH DISABILITIES If you have a documented disability, you can arrange for accommodations by contacting Disability Resources (DR) at 523-8773 (voice) or 523-6906 (TTY), dr@nau.edu (e-mail) or 928-523-8747 (fax). Students needing academic accommodations are required to register with DR and provide required disability related documentation. Although you may request an accommodation at any time, in order for DR to best meet your individual needs, you are urged to register and submit necessary documentation (www.nau.edu/dr) 8 weeks prior to the time you wish to receive accommodations. DR is strongly committed to the needs of student with disabilities and the promotion of Universal Design. Concerns or questions related to the accessibility of programs and facilities at NAU may be brought to the attention of DR or the Office of Affirmative Action and Equal Opportunity (523-3312). INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW BOARD Any study involving observation of or interaction with human subjects that originates at NAU—including a course project, report, or research paper—must be reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) for the protection of human subjects in research and research-related activities. The IRB meets monthly. Proposals must be submitted for review at least fifteen working days before the monthly meeting. You should consult with your course instructor early in the course to ascertain if your project needs to be reviewed by the IRB and/or to secure information or appropriate forms and procedures for the IRB review. Your instructor and department chair or college dean must sign the application for approval by the IRB. The IRB categorizes projects into three levels depending on the nature of the project: exempt from further review, expedited review, or full board review. If the IRB certifies that a project is exempt from further review, you need not resubmit the project for continuing IRB review as long as there are no modifications in the exempted procedures. A copy of the IRB Policy and Procedures Manual is available in each department’s administrative office and each college dean’s office or on their website: http://www.research.nau.edu/vpr/IRB/index.htm. If you have questions, contact the IRB Coordinator in the Office of the Vice President for Research at 928-523-8288 or 523-4340. ACADEMIC INTEGRITY The university takes an extremely serious view of violations of academic integrity. As members of the academic community, NAU’s administration, faculty, staff and students are dedicated to promoting an atmosphere of honesty and are committed to maintaining the academic integrity essential to the education process. Inherent in this commitment is the belief that academic dishonesty in all forms violates the basic principles of integrity and impedes learning. Students are therefore responsible for conducting themselves in an academically honest manner. Individual students and faculty members are responsible for identifying instances of academic dishonesty. Faculty members then recommend penalties to the department chair or college dean in keeping with the severity of the violation. The complete policy on academic integrity is in Appendix G of NAU’s Student Handbook http://www4.nau.edu/stulife/handbookdishonesty.htm. ACADEMIC CONTACT HOUR POLICY The Arizona Board of Regents Academic Contact Hour Policy (ABOR Handbook, 2-206, Academic Credit) states: “an hour of work is the equivalent of 50 minutes of class time…at least 15 contact hours of recitation, lecture, discussion, testing or evaluation, seminar, or colloquium as well as a minimum of 30 hours of student homework is required for each unit of credit.” The reasonable interpretation of this policy is that for every credit hour, a student should expect, on average, to do a minimum of two additional hours of work per week; e.g., preparation, homework, studying. Thus it is expected that you will engage in six hours of outside work per week for this course. SENSITIVE COURSE MATERIALS If an instructor believes it is appropriate, the syllabus should communicate to students that some course content may be considered sensitive by some students. “University education aims to expand student understanding and awareness. Thus, it necessarily involves engagement with a wide range of information, ideas, and creative representations. In the course of college studies, students can expect to encounter—and critically appraise—materials that may differ from and perhaps challenge familiar understandings, ideas, and beliefs. Students are encouraged to discuss these matters with faculty.” University policies: Attach the Safe Working and Learning Environment, Students with Disabilities, Institutional Review Board, and Academic Integrity policies or reference them on the syllabus. revised 8/08 9