St Kitts and Nevis, Macroeconomic Framework

advertisement

A Macroeconomic Framework for St Kitts and Nevis

Contract N° 2010/247214

Framework Contract Beneficiaries Lot 11: Macro economy, Statistics, Public Finance

Management

Professor Paul Hare and Mr Richard Stoneman

October – December, 2010

Table of Contents

List of Tables and Charts

Glossary

Executive Summary

1. Introduction

2. Outline of a Macroeconomic Framework

2.1

2.2

2.3

2.4

2.5

2.6

2.7

2.8

The real balance

The general government balance

The balance of payments

The monetary balance

Connections between the four accounts

Indebtedness

Competitiveness

Economic growth

2.8.1 Investment

2.8.2 Productivity growth

2.8.3 Institutional improvements

2.8.4 Sources of demand

3. Implementing the Framework on St Kitts and Nevis

3.1 Data Issues

3.1.1 Measuring GDP

3.1.2 GDP Projections

3.1.3 Projecting Government Spending and Revenues

3.2 Improving and Strengthening the Framework: Economic Issues

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

References/Reports Consulted

Annexes

Annex 1. Indebtedness Analysis

Annex 2. Definitions and Accounting Conventions

Annex 3. Extending the Macro-framework to Several Years

Annex 4. Dealing with Risk

DRAFT, v7, 11/12/10

List of Tables and Charts

Table 1. National income and expenditure for St Kitts and Nevis, 2007-2012

Table 2. Government accounts for St Kitts, 2008 to 2012

Table 3. Balance of payments for St Kitts and Nevis, 2008, 2009 and 2010

Table 4. St Kitts and Nevis: Monetary Survey, 2007-August 2010

Table 5. St Kitts and Nevis: Public debt and debt servicing, 2007-2010

Table 6. Three examples of value added calculations

Table 7. PSIP projects and their budgetary impact

Figure 1. Inter-connections between the four main macroeconomic accounts

Table A1. Debt-to-GDP ratios; the impact of policy variables

2

Glossary

ACP

APD

CARICOM

CARIFORUM

CARTAC

CDB

CGD

DSA

ECCB

ECCU

EC$

EPA

EU

FDI

GDP

GEOB

GoSKN

IFI

IMF

MF

MPC

MSD

MTESP

NAO

NHC

NIA

NTB

OECD

OECS

OHE

PSIP

QE

SITC

SKN

SNA

VAT

WTO

African, Caribbean and Pacific (countries)

Air Passenger Duty (a UK excise duty)

Caribbean Community

Caribbean Forum of ACP States (15 states)

Caribbean Regional Technical Assistance Centre

Caribbean Development Bank

Commission on Growth and Development

Debt Sustainability Analysis

Eastern Caribbean Central Bank

Eastern Caribbean Currency Union

Eastern Caribbean dollar

Economic Partnership Agreement

European Union

Foreign Direct Investment

Gross Domestic Product

Government Entities Oversight Board

Government of St Kitts and Nevis

International Financial Institution

International Monetary Fund

Ministry of Finance, SKN

Monetary Policy Committee (of the Bank of England)

Ministry of Sustainable Development, SKN

Medium Term Economic Strategy Paper

National Authorising Officer (Permanent Secretary in MSD)

National Housing Corporation

Nevis Island Administration

Non-tariff barrier

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development

Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (8 countries)

Offshore higher education

Public Sector Investment Programme

Quantitative easing

Standard International Trade Classification

St Kitts and Nevis

System of National Accounts

Value added tax

World Trade Organization

3

Executive Summary

1. This report presents our analysis, findings and recommendations concerning economic

aspects of the macroeconomic framework for St Kitts and Nevis. Accompanying reports

discuss organisational and institutional aspects of implementing our proposed

macroeconomic framework, discuss training needs related to the framework, and provide

a training manual to guide the future training of staff in the Ministry of Sustainable

Development and the Ministry of Finance who would be working on the framework.

Introduction

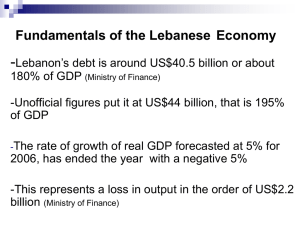

2. St Kitts and Nevis is a small and very open economy that has been badly affected by the

recent recession, and has uncomfortable levels of government debt, now approaching

200% of the GDP (according to the IMF). Managing this debt is in our view the most

urgent problem for the government to deal with, and we believe that a sound

macroeconomic framework provides the tools for doing so.

Outline of a Macroeconomic Framework

3. Accordingly, this report has explained in general terms what should be meant by a

macroeconomic framework and how and why it is useful in supporting analysis of the

behaviour and performance of an economy, with particular emphasis on the public

finances. The eight elements or components around which the macroeconomic

framework was examined were:

(a) the real balance

(b) the government balance

(c) the balance of payments

(d) the monetary balance

(e) connections between the above four basic balances

(f) indebtedness

(g) competitiveness

(h) economic growth

4. In each case, general introduction to an element in the framework was followed by

discussion and analysis of points particularly relevant to the economy of SKN. Indeed this

is why item (f) was highlighted especially strongly, since it is critical for the future of the

country, whereas in discussing other countries it might have been relegated to a far less

prominent position in the framework.

5. Items (a) to (d) concern the four basic balances of the economy, though since SKN

belongs to the ECCU, its monetary policy is handled – for the whole OECS sub-region –

by the ECCB. Likewise, the ECCB maintains the exchange rate of the EC$ against the

US$, which has remained fixed at EC$ 2.7 = US$ 1 for over 30 years.

6. Accordingly, while having regard for the monetary balance and the balance of payments,

GoSKN is most able, through its policy choices, to influence the first two balances,

namely the real balance and the government balance. Fiscal policies – tax rates,

expenditure decisions, and the like – must therefore be chosen to achieve the best feasible

outcome in these balances, given government priorities and all known constraints.

7. Item (e) highlights inter-connections among the basic balances, emphasising, however,

that the fact of multiple inter-connections does not entail the need for any single

economic authority controlling everything. Instead, economies generally work best with

4

multiple authorities, provided that there is a well designed structure of communication

between them.

8. The fundamental reason for having a well constructed macroeconomic framework for

SKN is to create the conditions for sustained economic growth to raise general living

standards and reduce poverty. This in turn, in such a highly open economy, also entails

promoting competitiveness. As background to both, given the country’s high and still

growing public debt, it essential for the indebted ness to be brought under better control.

These three issues – debt, competitiveness and economic growth – are the subjects of

items (f), (g) and (h) in the macroeconomic framework.

9. On indebtedness, we propose the use of a new, simple to use debt sustainability tool that

makes it quick and easy to check whether the public debt-to-GDP ratio is on a declining

trend or not, and to explore alternative fiscal policies to achieve any desired path.

Naturally, as in all analyses of this sort, debt sustainability is far easier to achieve when

the economy as a whole is growing fairly rapidly, say at 5% per annum or faster.

10. Hence the purpose of the subsequent analysis of competitiveness and growth is precisely

to explore the conditions under which such a growth rate might be achievable, and the

sorts of practical and detailed policy intervention that can help to do so.

Implementing the Framework

11. Moving on to implementation of the macroeconomic framework, the report reviewed

some important data-related issues and then considered ways of improving the existing

practices and procedures on SKN, focussing on a number of critical economic issues.

12. As regards the data, this was discussed in three stages, starting with estimating the real

GDP of SKN using the output method. Then the GDP has to be projected forwards to the

relevant budget year and the two following years, which is done by projecting output

sector-by-sector and summing the results using appropriate weights. Finally, the GDP

projections, along with other data where relevant, are used to estimate budgetary revenues

for the forthcoming budget year and the two subsequent years. The MF then has a basis

for drawing up the rest of the budget, since with revenue estimates and knowledge of

priority spending needs – on debt servicing, public sector pensions, and civil service

wages – it can estimate what (limited) funds will be available to meet the non-salary

spending needs of the various line ministries, including the social safety net.

13. Four critical economic issues were highlighted, and these form the basis for our principal

conclusions concerning economic aspects of the macroeconomic framework.

Economic Issues

14. SKN’s present government debt, with current government policies, is plainly

unsustainable. However, while we expect GoSKN to honour its debt obligations, we

would advise the government to engage in discussions with the major creditors with a

view to refinancing much of the debt to longer maturities, and perhaps better terms. We

would expect the ECCB and IMF to be helpful partners in such discussions.

15. With or without some debt rescheduling of this sort, we conclude there there are really

only two effective ways of bringing down the country’s debt to more manageable levels.

The first entails a period of severe fiscal pain in order to generate primary surpluses that

5

might need to be as high as 20% of the GDP (rather less than this if the economy can

deliver more rapid GDP growth) – though as this would amount to roughly 50% of

government revenues, it may be difficult to achieve.

16. The second approach might therefore prove more feasible initially. This entails the sale of

public assets, which might involve a mix of land sales and the privatisation of publicly

owned entities. If this approach is to be pursued, however, some early decisions would be

needed to get the process started, and the programme should then be pursued with vigour.

17. After two-three difficult years, GoSKN would gradually regain both a degree of ‘fiscal

space’ allowing it a little more flexibility over public spending plans, and would also get

its indebtedness down to levels where the country could more readily cope with an

unexpected adverse shock (such as another damaging hurricane).

18. It is high time for all SKN’s public enterprises (i.e. government departments delivering

services; public enterprises proper; and a variety of statutory corporations) to be put on a

sound economic footing.

19. No economic service activity should remain as a government department, and in our view

this implies the immediate corporatisation of such entities as the Electricity Department

on St Kitts (we understand that preparations for this are well under way, with

corporatisation likely in 2011). It is also important, for all entities providing a marketable

service, that economically sensible prices should be charged to all customers, and that all

should pay.

20. Further, wherever possible we would urge that these public entities be privatised at the

earliest opportunity, while any that cannot be restructured to enable them to cover their

costs should normally be closed down.

21. Many PSIP projects have implications for future current public spending, and these

should be embedded in the annual budget cycle estimates.

22. Although there are no doubt many good quality PSIP projects that could be developed

and implemented, it is unwise for GoSKN itself to fund such projects beyond current

commitments, until the country’s debt position has been brought under much better

control (aside from any spending needed to deal with national emergencies). However,

once the debt position had improved, one of the early benefits could be the opportunity

for the government to start funding some new PSIP projects.

23. Regarding improving forecasting methodology, we have not chosen to make any

recommendations of a technical nature. For although some mostly minor technical

improvements could undoubtedly be made in the present methods for forecasting GDP,

public spending and finally the overall SKN budget (with parallel processes for the Island

of Nevis), our main concern has been with wider aspects of the current budgetary

processes.

24. Specifically, we consider it desirable for the entire budgetary process, from start to finish,

to be conducted far more publicly than has been the norm in the past. For this to work,

regular reports on GDP projections, budget revenue projections, the overall budget, and

the subsequent monitoring and review processes need to be published rapidly on MSD

6

and MF websites as appropriate. Such reports should not merely publish the basic data,

but there also needs to be some analytical commentary to accompany the data.

25. This will facilitate public discourse on budgetary issues, a vital element of democratic

life, and will also strengthen public accountability of all aspects of the government

budget, including the all important handling of public sector debt and the public

enterprises.

Further Issues

26. Multi-year budgeting was referred to in the main text and is potentially an important

extension of the framework that we set up and analyse in this report. The most important

aspects of multi-year budgeting are addressed in summary form in Annex 3. Although it

has many strengths, we do not see moving to comprehensive multi-year budgeting as an

urgent priority for SKN, largely on resource cost grounds, though we acknowledge that

elements of such an approach are already in place and working well..

27. Dealing with risk. Again this was referred to in the main text, but we decided that to

discuss it properly would have entailed deviating far too much from our main line of

argument, and this could have caused unnecessary confusion. Accordingly, an overview

of the topic is provided in Annex 4.

7

A Macroeconomic Framework for St Kitts and Nevis1

1. Introduction

St Kitts and Nevis (SKN) is a very small highly open, middle-income economy facing

significant vulnerabilities both to natural factors (notably hurricanes) and to economic cycles

in the world economy that affect key markets – both for exported goods, and for services

such as finance and tourism. Thus the world financial crisis and recession that began in 2007

and which adversely affected virtually all advanced economies has had major knock on

effects on most other economies, including that of SKN. Aside from its direct impact on

trade, the crisis has also led to falls in income from remittances to SKN, and has made the

conditions for foreign direct investment (FDI) far less promising than they seemed just a few

years ago.

This situation would have been difficult enough to manage, but for SKN the economy faces

an additional challenge, namely the country’s exceptionally high public sector debt-to-GDP

ratio (around 185% and still rising), and this necessarily has to be managed carefully as part

of any credible macroeconomic framework. The debt has grown so large for a number of

reasons. First, several hurricanes during the 1990s inflicted severe damage, and the

government undertook substantial borrowing to rebuild housing and restore the economy.

Second, the state-owned sugar industry accumulated losses over several years, and was

closed in July 2005, with large additional costs associated with that decision; taken together,

sugar added about 29 percent of GDP to overall public sector debt. Third, various public

entities have regularly recorded losses that have contributed to the rise in public sector

indebtedness (because their losses and debts are understood to have government guarantees).

Fourth, considerable and generally much needed infrastructure investment has taken place in

the past decade or so, some of which has been financed by additional public sector borrowing

in the expectation that subsequent growth and higher tax revenues would allow the debt to be

serviced without undue strain. The combined effect of these factors gives SKN the very high

debt levels with which it must now contend2.

In an important sense, while the above points help to explain the background to SKN’s

current high indebtedness, what really matters now for the SKN economy is not specifically

why and how the current debt levels arose, but how they can now be managed and reduced,

as part of the country’s overall macroeconomic policy. These issues are explored in depth

later in this report.

Meanwhile, it is worth pausing briefly to consider ways in which the small size of the SKN

economy affects how one should most appropriately analyse and think about it. Most

obviously, the usual substantial ‘gap’ between the micro-economy and the macro-economy

makes little sense for SKN, since we are dealing with an economy of around 50,000 people

earning an income per capita of around US$ 11,000. Thus, roughly speaking, the entire

economy has a GDP amounting to little more than US$ 0.5 billion, truly tiny. This means that

the fortunes of any single firm employing a hundred or more people – of which there are

several – have a noticeable impact at the macroeconomic level via tax revenues generated by

the firm, the associated wage and salary bill (affecting personal consumption), and exports

and imports. In addition, just a handful of significant investment projects – such as housing

The authors are grateful to the NAO’s office for the provision of useful comments on an earlier, incomplete

draft of this report. Remaining errors and infelicities are our own.

2

There are also additional contingent liabilities of the government, such as future pension obligations, that we

do not account for explicitly in the present report.

1

8

developments, hotel projects, infrastructure developments or whatever – suffice to generate a

ratio of investment to GDP that would otherwise be considered surprisingly high.

Correspondingly, a pause in major investment projects and/or the closure of just a few

significant firms would be sufficient to bring about a significant fall in the equilibrium

income level.

Thus as the recession unfolded, the Marriott holiday complex at Frigate Bay, St Kitts,

temporarily laid off many workers, while hurricane damage in 2008 forced the closure of the

Four Seasons Resort on Nevis; after extensive reconstruction, this is due to re-open in

December 2010. For a small economy, these two events both have to be regarded as major

shocks. In this sense, the SKN economy is likely to experience relatively greater volatility

than one might expect in a much larger economy. This needs to be taken into account in the

design of appropriate economic policy.

A further aspect of SKN’s smallness has to do with its implications for the political

environment. On the one hand, everyone of importance – both in politics and business –

knows everyone else, and one might expect that to facilitate constructive communication that

could actually be quite helpful for managing the economy. To an extent that might be correct,

but our over-riding impression is much less benign than that, namely that the extensive

informal links between politicians, senior civil servants and the business community tend to

facilitate informal ‘protection’ and forbearance in regard to firms experiencing difficulties.

Firms can and do argue that if they are not ‘helped’ there will be job losses that will be

damaging to the local economy, and politicians don’t like to see that, for fear they may be

held responsible – so tax arrears are tolerated, as are arrears in utility payments. Moreover,

the more formal consultations between government and business that take place each year

over the government’s budget and other aspects of economic policy appear not to work well,

as they are perceived by the business community more as information sessions – in other

words, the government simply tells business what it has already decided to do.

2. Outline of a Macroeconomic Framework

“The macroeconomic policy framework over the medium term will aim to maintain a

favourable macroeconomic environment necessary for increasing competitiveness in the

production of goods and services and sustaining economic growth in SKN.” (Medium Term

Economic Strategy, 2010-2013, Volume II, p33, draft).

This statement, from a useful draft report published earlier this year (2010), sums up

succinctly and well the key reasons why St Kitts and Nevis would benefit from a carefully

formulated macroeconomic framework, namely to promote competitiveness in production,

which essentially means creating conditions under which local production can meet market

demands in both domestic and foreign markets; and to foster sustained growth of GDP. In

order to achieve these highly desirable outcomes, the basic economic conditions on SKN first

need to be stabilised, notably to ensure that the country’s large debt overhang can be

managed without unduly harming medium and longer term growth.

The natural starting point for thinking about a country’s macroeconomic framework,

however, has to do with the four basic economic balances that represent the current situation,

namely: (i) the real balance; (ii) the general government balance; (iii) the balance of

payments; and (iv) the monetary balance. In what follows, therefore, we briefly discuss each

balance, first in generic terms and then with reference to SKN.

9

This discussion of basic balances provides the necessary background to our subsequent

analysis of debt and the public sector accounts. Next, we go on to examine competitiveness

issues; and finally we bring everything together by analysing economic growth. In the course

of the analysis, we shall naturally need to pay some attention to employment and job creation

on SKN, as well as the maintenance of reasonably stable prices, always important for

economic security and business confidence.

In SKN’s current practice, GDP is projected three years ahead (i.e. for the coming budget

year and the two following years), and the budget itself is presented for the budget year plus

projections for the two subsequent years. The PSIP also looks three years ahead. In this

sense, elements of a multi-year macroeconomic framework are already in place and are well

established. However, the core of current practice on SKN is based on projections for the

budget year itself, and to this extent it remains in its essentials a single-year framework

(albeit with improvements).

However, we note the recommendations of CARTAC and the IMF that a sound

macroeconomic framework should ideally be built around a multi-year approach to

forecasting, budgeting, and so on. Accordingly, in Annex 3 we outline the advantages and

disadvantages of developing a comprehensive multi-period framework. We also note the

resource costs of doing so.

2.1 The real balance

The real balance for an economy describes conditions in the markets for goods and services

for a given accounting period, typically a year. Part of the balance is an accounting identity

(by which we mean a relationship that has to be true, regardless of concrete economic

circumstances). This is commonly expressed in the form of the familiar income-expenditure

identity that arises in national income accounting. The identity is shown as equation (A1) in

Annex 1, and is repeated here for convenience.

Y=C+I+G+X–M

(1),

where:

Y = GDP (gross domestic product)

C = personal consumption

I = investment (gross fixed capital formation + change in inventories)

G = government demand for goods and services

X = exports of goods and services

M = imports of goods and services

In most larger economies, GDP is measured independently in both ways implied by equation

(1). Thus taking the left hand side first, output in the economy is measured by adding up the

value added in each sector of the economy, which gives the total, Y, usually measured in

producer prices or basic prices. The result is the output-based measure of GDP, and we

discuss it more fully later, in section 3.1.1 of this report; this is the main way of measuring

the GDP in St Kitts and Nevis at present.

Next, the right hand side of (1) is the sum of various expenditure components, as listed below

the equation. These are usually measured independently, to give a second measure of the

GDP of the country, the expenditure-based measure. In SKN, however, as we explain below,

only certain parts of the expenditure are measured directly, with personal consumption, C,

being obtained as a residual. What this means is that those expenditure components that are

10

actually measured are deducted from the output-based GDP to obtain an estimate for C. In

doing this, account must be taken of the fact that expenditure components are normally

measured in market prices, while, as noted, output is measured in basic or producer prices 3.

Hence one side or the other in (1) needs adjustment to ensure that both are measured in

equivalent prices. For convenience, some of these price definitions and other accounting

conventions are brought together into Annex 2.

Table 1 shows the output and expenditure accounts for St Kitts and Nevis for recent years, in

order to illustrate the above.

Table 1. National income and expenditure for St Kitts and Nevis, 2007-2012

Item

2007

2008

2009

1202

2010

Proj.

1195

2011

Proj.

1240

2012

Proj.

1287

GDP in current basic

prices, output measure

Nominal growth rate, %

(MTESP)

Real growth rate, %

(SKN Stats)

GDP in current market

prices, expenditure

measure

Nominal growth rate, %

Personal consumption

Government

consumption

Capital formation

Exports of goods and

services

Imports of goods and

services

1138

1264

7.6

11.1

-6.1

0.7

3.8

3.8

4.2

4.6

-9.6

-1.4

1.1

1.6

1386

1539

1471

1431

1486

1541

5.4

845

258

11.1

1149

263

-7.7

1094

288

0.7

3.8

3.8

594

610

627

591

583

517

922

1092

1011

Source: MTESP (2010), Annex 3; ECCB (2009)

Notes: Figures are in million EC$, except where stated.

Since the output measure of GDP is built up from data on different branches of the economy

(see section 3.1.1), we naturally have available data on the structure of GDP by broad sector,

and from this it turns out the banking and insurance, government services, construction,

wholesale and retail trade, tourism, and manufacturing each accounts for over 10% of the

GDP; no other sector exceeds 5% of GDP. More importantly in some ways, it would be

useful to know about the respective GDP levels – and per capita GDPs – in St Kitts and Nevis

separately, but this information is not currently available4. We understand that separate GDP

estimates for the two islands are in preparation, and may be available early in 2011. This will

be useful, partly for its inherent interest, partly for the practical reason that it will help the

3

See Annex 2 for definitions.

Based on driving round each island and informally assessing housing standards, services available to visitors,

and the quality of local infrastructure, we would not be surprised if per capita GDP on Nevis turned out to be

25% higher than that on St Kitts.

4

11

authorities on St Kitts and Nevis to reach a satisfactory and equitable revenue sharing rule for

the new Value Added Tax (VAT)5.

Now, aside from the basic accounting identity that we have been discussing, which will

always hold (leaving measurement errors aside), the real balance also concerns the level of

economic activity in the given economy relative to some notion of full capacity. Ideally,

policy-makers seek to achieve a level of activity that is as close as possible to full

employment, through a judicious mix of fiscal and monetary policy instruments. When

employment is too high in relation to the available labour force, there tends to be upwards

pressure on money wages which, with a fixed exchange rate, tends to harm competitiveness

in external markets; and conversely if employment is too low.

In SKN, there is no regular data collection concerning the labour force, employment,

unemployment and the like, so it is not so easy to judge the state of the labour market.

However, it would not be too difficult to assess current wage settlements in a sample of firms

and other workplaces, including the public sector, as a basis for making a reasonably well

informed judgement. Certainly, if wages rose too fast, in particular at a faster rate than

average productivity was growing, then there would be upwards pressure on prices, and this

would be picked up quite rapidly by the authorities as consumer prices are surveyed monthly

and a consumer price index calculated. Recent reports show consumer prices rising at under

5% per annum except in 2008 where the inflation rate was closer to 8% (IMF, 2009a), and

the latest CPI data on the ECCB website shows inflation close to zero.

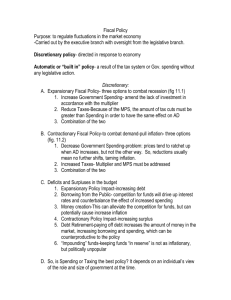

When considering the policies that can be used to influence the state of a country’s real

balance, it is usual to look to the tools of fiscal policy. In other words, features of the tax

system such as tax rates, the tax base, and elements of public spending can all, in principle,

be adjusted in order to achieve some desired level of equilibrium national income (GDP),

presumably at or close to full employment. However, governments never enjoy complete

freedom in this regard, since the decisions they would like to take to do with tax rates and

government spending also influence – and are influenced by – the government’s own

financial balance, to which we turn next.

2.2 The general government balance

Governments raise money through taxes and a variety of non-tax charges (e.g. fees for

specific services, licences and the like) and use it to pay for public administration itself (civil

service salaries and non-salary administrative costs), publicly provided services such as

schools, health clinics, the police, and so on. In addition, governments make a variety of

transfer payments to individuals, like pensions, and to firms (including public enterprises),

notably specific subsidies. Here we make no judgements about the economic desirability or

otherwise of any of these transactions, merely noting the wide range of possibilities that need

to be allowed for in the public accounts. These are all current transactions of the government.

Capital account transactions also occur, involving both asset sales and public investment (i.e.

the part funded by government), the latter mostly involving projects to develop the public

infrastructure; in SKN, these projects – whether funded by government or from other sources

5

The recently reported temporary revenue sharing agreement for the VAT gives Nevis 24% of the revenues

(with the remaining 76% going to St Kitts), and since Nevis has roughly 20% of the total SKN population, this

amounts to assessing the Nevis GDP per head 26% above that of St Kitts. On the hand, it remains arguable

whether the outcome is wholly fair to Nevis, since the taxes dropped when the VAT was introduced accounted

for a relatively higher share of NIA government revenues.

12

– are brought together to form the Public Sector Investment Programme (PSIP). Last, after all

these transactions are listed, the resulting government accounts can show either a surplus or a

deficit – in either case, this is called the primary balance.

Normally, governments have in the past funded themselves partly from tax revenues as just

discussed, and partly through borrowing, generally by selling securities of various maturities

on the private financial markets, and sometimes by selling them to the Central Bank; in

addition, most governments have the option of financing part of their spending though

printing money, a power that should be used sparingly in order not to stimulate inflation.

Within the OECS region, individual governments do not enjoy this particular power, since

the monetary system is overseen by ECCB, and all commercial banks are required to follow

the ECCB’s Prudential Guidelines governing large exposures. However, concerns are

sometimes expressed that some actions of member governments are tantamount to money

creation, for instance when governments make excessive use of local bank overdraft facilities

to fund their activities.

As a result of past borrowing, for whatever reason, governments enter the current period with

a certain level of accumulated debt. This can be denominated entirely in the domestic

currency, or in a mix of domestic and foreign currencies, depending on how the financing of

past deficits was undertaken. In the current period, the government will obviously have to

service the outstanding debt.

Debt servicing takes three forms. First, interest will be payable on the outstanding principal.

Second, some repayments of principal may fall due in the current period, and these

repayments also have to be allowed for. Meeting these two types of charge entails outgoings

from the government budget. Depending on the overall financial position of the government,

such outgoings can be wholly or partly offset by taking on new borrowing, the third aspect of

debt servicing. Such borrowing can be used to ameliorate the flow of future repayments by

improving – generally extending – the maturity structure of the outstanding debt; or it can

reflect a decision by government that the country’s financial position is sufficiently secure

that it can afford to take on additional debt without putting the country’s financial stability at

risk.

The overall balance in the government’s accounts is then the net (combined) result of all

these transactions except the third type of debt servicing just referred to. And whether a given

balance is ‘good’ or ‘bad’ depends on the context, the wider economic circumstances in

which the government finds itself, as we shall explain more fully below. If the overall

balance is positive (a surplus), the outstanding debt is being fully serviced and some may be

being paid off. If the balance is negative, servicing can only be managed by incurring new

debt, essentially through refinancing operations.

To complete this summary of the government’s balance, two further points need to be

brought into the discussion. The first has to do with a range of off-balance-sheet transactions

that governments often choose to keep separate from their main accounts. For instance, social

security funds are often handled this way, the justification being that such funds should not be

accounted for as if they were simply another part of the government’s budget, since they are

set up for a specific purpose and are not intended to finance general government spending.

Explanations along these lines, though, are not entirely fair, however, for two reasons:

(a) when they have accumulated surpluses, social security funds sometimes lend to their

13

government; when they have deficits, they borrow from their government to meet their

commitments, e.g. to pensioners. Hence to gain a realistic and complete picture of the public

finances, it is normally considered good practice to consolidate the general government

budget with all such off-budget funds.

Table 2. Government accounts for St Kitts, 2008 to 2012

Item

2008

2009

2010

Est.

2011

Est.

2012

Est.

635

509

2010

(1-8)

Exp.

311

273

2010

(1-8)

Act.

287

261

1.Total revenue and grants

Recurrent revenue

Of which:

Tax revenue

Non-tax revenue

Capital revenue

Grants

523

432

596

454

617

433

628

486

337

96

62

28

363

91

77

66

319

114

105

79

368

119

91

51

386

123

84

41

198

75

27

11

172

88

11

16

2.Total expenditure

Recurrent expenditure

Of which:

3.Interest payments

Capital expenditure and

net lending

511

428

558

447

536

430

544

438

514

430

333

278

329

269

111

83

124

111

106

106

105

106

100

84

68

55

69

59

Overall balance (1 – 2)

12

4.Primary balance (1 - 2 + 123

3)

38

162

81

188

84

189

121

221

-22

46

-41

28

5.Principal payments

70

64

76

140

120

43

38

New debt (5 + 3 – 4)

58

26

-6

56

-1

65

79

Source: Estimates (2010); Monthly Fiscal Data, Jan-Aug 2010, Excel spreadsheet, St Kitts:

GoSKN. Figures for 2008 and 2009 are actual out-turns.

Notes: All figures are in million EC$. The data shown in the table are reported in current

prices. Rounding errors mean that some sub-totals appear not to sum to the correct total. Last

row – authors’ calculation.

The same is true for revenues and outlays associated with publicly-owned enterprises, or

public production even if not set up using a commercial model, since they too enjoy implicit

(and often explicit) government guarantees to fund any deficits that might arise, and to

finance their accumulated debts. For SKN, this category of activity includes public

corporations, various statutory bodies and, in effect, certain government departments. Thus

electricity production in St Kitts is still organised as a government department, though there

are plans to commercialise it shortly; while electricity on Nevis is already organised as a

public corporation. Other bodies include the port authority, the NHC, and a number of

others. Several of these activities have been surprisingly delinquent over the production of

up-to-date, audited accounts, while collectively they have amassed substantial debts with

14

minimal accountability. The recent creation of a Government Entities Oversight Board to

monitor these activities is therefore an important and very useful step; however, its remit is

limited to the public corporations on St Kitts, so does not include, for instance the St Kitts

electricity supply body (see GEOB, 2009).

Second, another form of budgetary consolidation is very important. Many jurisdictions have

multiple levels of government such as nation, province, county, and so on, and to obtain a

complete picture of the public sector/government accounts it is essential to consolidate the

accounts across all these levels. For SKN this is relatively simple, since the country is

constitutionally a Federation with two principal constituent units, namely the Federation of St

Kitts and Nevis, and the Nevis Island Administration. Hence to form consolidated

government accounts, or accounts for general government to use the standard IMF

terminology, we simply need to combine the two sets of government accounts, that for St

Kitts, and the other for Nevis..

Table 2, above, shows the government accounts for St Kitts for 2008 and 2009, together with

the approved estimates for 2010, 2011, 2012 and some data on budget out-turns for the early

months of 2010. This all serves to illustrate the above discussion. We have not shown here

the separate Nevis accounts, or the consolidated accounts.

Using the Table 1 data on GDP in market prices for 2009, we can see that in that year, from

Table 2, total government spending (capital plus current) amounted to 39.3% of GDP, while

total revenues were 41.9%. Expenditure on servicing the country’s debt, both interest

payments and principal, came to 13.2% of GDP, and 31.5% of gross government revenue.

The corresponding figures projected for 2010 were expected to be as follows. Total

government spending was expected to be 37.5% of GDP, with total revenues coming out at

43.1%. Total debt service was planned at 12.7% of GDP, 29.5% of total budgetary revenues.

Up to August 2010, however, the public finance out-turn was looking less favourable than

planned, with total spending close to target, and total revenues about 8% down.

It is not yet clear how much the position might recover by year end, but for the moment the

implication is that GoSKN has been obliged to take out new debt this year in order to service

the existing debt on time. Actually, much of the new debt takes the form of borrowing for

urgent capital projects, namely the purchase of new generator sets for St Kitts.

Nevertheless, instead of remaining static or even falling slightly as planned, the county’s

outstanding public debt has been on the rise again in 2010, as confirmed by IMF (2010a). We

discuss the wider implications of this position later in the report, where we shall show that the

current and likely future position of SKN as regards debt and the burden of debt servicing

departs substantially from the relatively optimistic picture presented in MTESP (2010).

When taking decisions about the types of taxes to impose, their scope, and the rates of tax, as

well as about the level and structure of government spending, governments must have regard

to the overall general government balance they wish to achieve in the current period. This in

turn will depend on the past history of deficits, the accumulated debt, and the desired future

path of the country’s indebtedness. For SKN under present conditions, these considerations

highlight the need to achieve substantial surpluses in the government’s primary balance to

enable existing debt to be serviced and its level gradually reduced. As we shall see later when

we analyse debt more carefully (section 2.6), this is a major challenge for SKN, and some

form of (managed) rescheduling cannot be ruled out.

15

Moreover, if it had more room to manoeuvre, the government of SKN might well prefer to

adopt a somewhat laxer fiscal stance in order to stimulate the aggregate level of economic

activity – for instance through additional public sector infrastructure spending, as proposed in

MTESP (2010, p.22) – given the impact of the financial crisis and subsequent world

recession that hit the islands especially hard in 2009. With the present barely manageable

debt levels, this is not really an option for the time being, in our view.

2.3 The balance of payments

All the international transactions of a country are brought together in its balance of payments

account. Conventionally, the account is split into two parts: the current account and the

capital account. The current account records exports and imports of goods and services, and

inward and outward flows of interest, profits and dividends. In addition, it includes flows of

remittance income in both directions, as well as aid flows and any other unrequited transfers.

The balance of all these current transactions is then referred to as the current account balance

of the balance of payments.

The capital account of the balance of payments includes all inward and outward capital flows.

These include foreign direct investment (FDI), portfolio investment, and a variety of shortterm capital flows. Normally, the balance of payments is presented in such a way that it does

indeed balance. This is accomplished in the following way. We take the current account

balance together with all the private sector capital inflows and outflows, and combining these

gives what is commonly referred to as ‘the balance of (international) payments’ for the

country. The remaining part of the capital account, which makes the overall account balance,

consists of transactions that are often referred to as ‘financing the balance of payments’; they

include increases or decreases in foreign exchange reserves, and external borrowing or

lending operations by government.

Table 3 shows the balance of payments for St Kitts and Nevis for 2008 and 2009, and with

estimated data for 2010, in order to illustrate these various types of transaction and to show

how they should be presented in the accounts. It can be seen that SKN consistently operates

with a large current account deficit in the balance of payments, amounting to somewhat over

one-third of GDP (as measured in market prices). This very large current deficit is, of course,

largely offset by the correspondingly large surpluses shown on the capital account of the

balance of payments, underlining the importance for the country of maintaining favourable

conditions for foreign investment of all kinds, especially FDI. For only under such conditions

can the present balance of payments be maintained in the medium and longer term.

Of course, since St Kitts and Nevis belongs to the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union

(ECCU), with the ECCB serving as central bank to the OECS sub-region, the balance of

payments for SKN per se does not matter in the way that it would for a country with its own

independent and freely floating currency. For instance within the UK, no one is especially

interested in the balance of payments for Scotland (though it is sometimes calculated/

estimated by economic analysts), since Scotland has belonged to the UK economic area for

several centuries already, using the pound sterling as the area’s common currency. Likewise,

within the Eurozone, there is little interest in the balance of payments for Belgium or

Slovenia. Again, these balances are sometimes still estimated, but the main interest focuses,

as it should, on the balance of payments for the entire Eurozone. This is what the European

Central Bank constantly monitors as part of its overall market surveillance, as background to

its monetary policy decisions.

16

Table 3. Balance of payments for St Kitts and Nevis, 2008, 2009 and 2010

Item

Current account

Goods and services

Income

Current transfers

Capital and financial account

Capital

Finance

2008

2009

2010 Est.

Credit

Debit

Net

Credit

Debit

Net

Credit

Debit

Net

784

1272

(488)

688

1187

(499)

656

1172

(516)

619

1103

(484)

510

1029

(519)

476

1014

(538)

27

120

(93)

25

113

(88)

25

113

(87)

138

49

89

153

45

108

155

45

109

754

254

60

694

500

1

253

789

59

441

287

18

772

502

1

286

604

17

485

88

43

562

516

1

88

42

474

Net errors and omissions

27

31

0

Overall balance

40

34

-

Financing

40

(40)

34

(34)

Source: MTESP (2010), Annex 3; ECCB data tables, various.

Notes: All figures are in million EC$. Some sub-totals might not sum to the totals shown due to rounding errors.

That said, it would not be correct to suggest that either the ECCB or the authorities in SKN

can safely regard the country’s balance of payments as a matter of indifference. On the face

of it, participation in a monetary union appears to create incentives – or at least the

opportunity – for individual member states to be relatively careless as regards international

transactions and their overall balance. However, this is not really the case, as a monetary

union can only be sustained for any length of time if the monetary authorities of the region

(in this case, the ECCB) are able to operate a prudent monetary policy that sustains the fixed

exchange rate between the Eastern Caribbean dollar and the US dollar (EC$ 2.7 = US$ 1),

maintains low inflation on average across the region, and maintains the balance of payments

for the monetary union as a whole in acceptable condition, as the ECCB has done quite

successfully.

Thus the ECCB, in managing the balance of payments across the entire union, must be in a

position to maintain adequate foreign currency reserves (mostly US dollars) to enable it to

support the trade and other international transactions of the member countries. In practice,

this is easier said than done, and among other things it requires the member countries of the

union to exercise a degree of restraint and prudence in the management of their individual

fiscal polices. This is essential, since across the union there has been no pooling of

sovereignty, no formal agreement on a union-level fiscal policy for the region6. Ideally, too,

the ECCB should hold sufficient foreign currency reserves to enable it to cope with the

economic shocks most likely to effect either member countries or the region as a whole.

However, IMF (2009b) suggests that under some circumstances, current levels of reserves

might not prove sufficient to manage such an eventuality.

As far as policy is concerned, the government of SKN has few macro-policy instruments

available to it if it wishes to improve its balance of payments, and the measures it can feasibly

take are generally microeconomic in nature rather than macroeconomic. For the usual

macroeconomic levers – the exchange rate and the interest rate – are both managed by the

ECCB for the entire region. The former, the exchange rate, is fixed as noted above. The

latter is determined as part of the monetary policy of the ECCB, as we discuss in the

following sub-section. That leaves a range of microeconomic measures, and they can take a

variety of forms which it is convenient simply to list briefly at this point, leaving a fuller

discussion until later in the report:

6

policies to encourage FDI;

policies to improve competitiveness and hence stimulate (net) exports of goods and

services;

policies to improve the trade regime by reducing average tariffs, simplifying the tariff

system, removing all or most special levies, rebates, and so on7.

industrial policy actions to foster activities in which SKN might reasonably be

expected to enjoy some comparative advantage, e.g. tourism; off-shore higher

education; selected manufacturing; fresh and processed agricultural produce;

specialised financial services; and possibly others.

The recent difficulties in the Eurozone illustrate some of the problems that can arise when fiscal discipline by

member states is insufficient, in an environment where rules established to foster collective discipline (the so

called Stability and Growth Pact) have been widely flouted. See Buiter (2010), Buiter and Rahbari (2010).

High-level meetings held in October 2010 to secure a new agreement on fiscal policy coordination and

discipline across the Eurozone yielded results that are neither convincing nor credible, in our view. The latest

financial crisis in Ireland (November 2010), unfortunately, illustrates this point all too well.

7

For a thorough review of the trade regime on St Kitts and Nevis, see WTO (2007).

policies to attract remittances;

policies to encourage wealthy individuals to establish local residency and citizenship.

2.4 The monetary balance

In formal terms, the monetary balance of a country describes the balance between the supply

of and demand for money, the standard assumption being that the monetary authority uses the

base rate of interest as its principal instrument for regulating the balance. However, in

practice the situation is a bit more complicated than this, and for SKN the picture is further

complicated by two factors: (a) the country’s membership of the ECCU; and (b) the limited

availability of traded government securities – GoSKN itself only offers three-month Treasury

Bills, and there is a very thin and limited market in longer-dated securities in the sub-region.

Let us now explain what all this means.

Normal practice is for the relevant central bank to collect data on the operations of the

financial institutions, both for public information, to facilitate analysis and to support

regulation. Thus, for example, the UK’s Bank of England regularly reports on money and

lending by the commercial banks; balance sheets and the income and expenditure accounts of

monetary financial institutions; public sector debt and money market operations; issues of

bonds, equities and commercial paper; financial derivatives; and interest and exchange rates.

The Bank also publishes a quarterly financial stability report that assesses the current position

in the financial markets and the wider economy in relation to the Bank’s objective (as agreed

with Her Majesty’s Treasury) of keeping inflation as close as possible to the target rate of 2%

per annum; the financial stability report also assesses the key risks facing the economy as

seen by the Bank. To achieve its inflation target, the Bank’s key policy instrument is the base

interest rate, which is set each month by the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the Bank,

whose Minutes appear on the Bank of England website not long after each meeting..

As a result of the financial crisis that began in 2007, the Bank has for a time paid more

attention to the overall level of activity in the economy than to its key inflation ‘target’, and

has used active ‘quantitative easing’ (QE) to get more money into the economy in the hope of

shortening the recession and preventing a so called ‘double-dip’. Similar action has been

taken in the Eurozone by the European Central Bank, and in the United States by the Federal

Reserve8, though it must be admitted that the ‘theory’ of how QE actually works is still quite

poorly understood. Moreover, once the advanced countries’ economic and financial situation

becomes more normal, their central banks are faced with the difficulty of how best to unwind

QE in a timely manner without either stimulating a burst of inflation or returning their

economies to recession conditions. Some delicate choices will be needed quite soon (see

IMF, 2010b).

SKN is part of the ECCU, with the region’s monetary policy and financial market regulation

overseen by the ECCB. Monetary statistics for SKN are collected and published by ECCB,

and Table 4, below presents data from the monetary survey of the country. M1 and M2 are

respectively narrow and somewhat broader definitions of the money supply.

8

In the first week of November, the Fed announced the start of a second round of quantitative easing, popularly

referred to as QE2. It is hard to see how this can have much impact on aggregate demand in the short-term,

though it may do so indirectly via its effect on longer term asset prices.

19

Table 4. St Kitts and Nevis: Monetary Survey, 2007-August 2010

Item

2007

2008

2009

Net foreign assets

558

747

632

Domestic credit, of which:

Government (net)

Private sector

Other public sector

1567

Monetary liabilities (M2), of 1625

which:

Monetary supply (M1)

226

Quasi-money, of which:

1399

Time deposits

Savings deposits

Foreign currency deposits

Other items (net)

1609

465

1173

-71

1677

337

1243

29

1746

375

1295

7

414

1375

-43

1651

1748

1821

252

1399

244

1504

276

1545

378

566

455

-500

2010,

August

657

398

603

398

-705

491

639

375

-561

523

645

376

-582

Source: MTESP (2010), ECCB (2010), ECCB website

Notes: All figures are in million EC$ and indicate outstanding stocks at end-of-period.

GoSKN has little discretion over matters of monetary policy, since the exchange rate is fixed

and base interest rates are set by the ECCB. In conducting monetary policy, the ECCB’s

policy objective is “To maintain the stability of the EC dollar and the integrity of the banking

system in order to facilitate the balanced growth and development of member states” (ECCB

website), and base interest rates are set periodically by the Monetary Council in order to

promote this goal. In practice, of course, being part of a fixed exchange rate system normally

leaves the authorities very little practical flexibility as regards setting these rates.

At the same time, regardless of the ECCU monetary policy stance, the SKN government

deficit has to be financed, as does the entire outstanding public debt of the country. In an

economy with only short-term securities and lacking a long-term bond market, there are

limited options, of which the principal ones would appear to be borrowing from domestic and

foreign banks. Given the existing level of indebtedness, domestic (and to a lesser extent,

foreign) banks’ exposure to SKN government debt has already reached worrying levels, with

the result that even a modest rescheduling of the country’s debt would put at risk the

liquidity, and possibly even the solvency, of some of the major local banks. Given these

dangers, it seems quite surprising that ECCB has not hitherto (to our knowledge) acted more

forcefully to control the indebtedless of local banks to GoSKN. That said, we acknowledge

that ECCB would wish to do all in its power to maintain orderly financial conditions, because

of the risks of contagion across the ECCU area.

2.5 Connections between the four accounts

We have now introduced the four accounts that, taken together, sum up a country’s

macroeconomic framework. In outlining the policies that are often used to influence one or

20

other balance, we already noted some of the main linkages between the accounts. But it is

important to understand that all four accounts are interconnected through several different

channels, and in designing sound macroeconomic policy this must always be kept in mind.

Figure 1 on the next page illustrates some of the key inter-connections, which we now briefly

discuss.

Some of the connections follow directly from writing down the basic accounts. Thus exports

and imports both appear in the real balance and in the balance of payments, government

spending on goods and services appears in the real balance and in the government balance.

Less direct, but still important connections are the following: (a) the government balance and

monetary balance are interconnected since government deficits and accumulated debt need to

be financed; (b) the monetary balance influences the real balance since much spending in the

latter requires credit from the banking system to support it; (c) the balance of payments

influences the monetary balance as net income from abroad, as well as some capital flows,

involves transactions with local banks. We conclude that it would be a serious error to try to

use policy to manage one or other of these accounts without taking into account their interrelations with the others.

Later, we show what this implies for the design of a well functioning and effective

macroeconomic framework for St Kitts and Nevis. For the moment, however, there is one last

general point that is worth making. This is the simple point that the unavoidable fact of

multiple inter-connections between the different elements of the framework does not imply

that the entire framework ought to be managed by a single authority. In other countries there

are always multiple authorities, each managing its own component of the macroeconomic

framework, and the situation should be no different in SKN. The issue, therefore, is never

how to achieve unified control – in most countries that is neither feasible nor desirable – but

rather how best to achieve good communication between the different authorities which,

collectively, are charged with the task of managing the economy.

21

Real balance

Balance of payments

Y=C+G+I+X-M

X-M plus net income from

abroad plus net capital

flows plus financing

Government balance

Tax revenues plus non-tax

revenues

Spending on goods and services

(G)

Spending on transfers

Deficit and debt

Monetary balance

Assets and liabilities of the

central bank (ECCB)

Assets and liabilities of the

commercial banks

Net lending to the private sector

Net lending to government

The Eastern Caribbean Central Bank

Figure 1. Inter-connections between the four main macroeconomic accounts

22

2.6 Indebtedness

We start this section by presenting some basic data on the debt situation of St Kitts and

Nevis, and its recent evolution. This is shown in Table 5, below.

Table 5. St Kitts and Nevis: Public debt and debt servicing, 2007-2010

2007

2008

2009

Item

Total stock of debt

2511

% of GDP in market prices 181

2619

170

2644

185

External debt (by debtor)

St Kitts Government

NIA

Public enterprises

818

891

2010 debt servicing

Principal Interest

77

106

5

7

830

49

37

External debt (by creditor)

Bilateral

Multilateral

Commercial

818

Domestic debt (by debtor)

St Kitts Government

NIA

Public enterprises

1690

1685

1816

28

1170

1134

1178

158

179

227

363

372

411

69

Domestic debt (by creditor)

ECCB

Commercial banks

Social security

Other

1690

462

111

246

578

100

213

891

510

109

211

830

105

289

424

92

303

490

1685

15

1194

248

234

1816

9

1085

252

339

Source: Estimates (2010), IMF (2009a), IMF (2008b); GoSKN (2010a), Appendix IV

Notes: Figures are in million EC$ except where noted.

From the table, it can be seen that the public debt-to-GDP ratio, which had been falling, rose

again substantially in 2009 and is reportedly continuing to do so9. In terms of structure, a few

years ago (not shown in the table) the total debt was divided about equally between domestic

and external debt, while by now the proportions have shifted, with external debt accounting

for under one-third of the total. Nearly two-thirds of the domestic debt is funded by the

domestic commercial banks, not a particularly comfortable situation. We understand that thus

far, servicing of government debt has been exemplary in the sense that all obligations have

been met; however, at times bank overdraft facilities have been used to enable due payments

to be made; this is not, of course, a desirable way of managing the debt, as such financing is

normally expensive and and in many countries would only be available against significant

collateral. In addition, some of the public enterprises are said to be in arrears in regard to their

Indeed, the IMF’s Public Information Notice on the St Kitts and Nevis: 2010 Article IV Consultation, estimates

that by end-2010 the debt-to-GDP ratio will have risen further to 196% of GDP (PIN 10/145, November 3 rd

2010, IMF website).

9

23

debt servicing obligations, though we lack detailed data on this. Overall, it is apparent that the

SKN debt situation has already reached a point where it is proving difficult for the authorities

to manage their day-to-day obligations.

The recently published study of debt and default through the ages, Rogoff and Reinhart

(2009), argued that a public debt-to-GDP ratio above 90% was high enough to slow down

growth and to create difficult conditions for the country concerned, with an increasing risk of

default as the ratio increases. What would be an ‘optimal’ debt-to GDP ratio is not entirely

clear, especially as economic theory provides virtually no practical guidance on the matter.

Empirical evidence from the above and other studies certainly favours relatively low ratios,

and this has been reflected in the ratios recommended by various bodies. Thus until the recent

crisis, the UK government operated for about a decade with the ratio targeted at around 40%

of GDP, while under the EU’s Maastricht Treaty, members of the European Monetary Union

were required to maintain the ratio below 60% of GDP. One suspects that these targets/limits

arose because they were perceived to be the lowest that were realistic at the time, rather than

as the outcome of a careful analytical exercise. In this sense, the targets were more political

in nature than economic. And neither the UK (Bank of England) nor the European Central

Bank proved able to hold the actual ratios close to their preferred levels, once the economic

crisis and recession took hold.

In the Eastern Caribbean, the ECCB has set a 60% debt-to-GDP ratio as its preferred or target

value, and members of the ECCU with ratios well above this target are ‘encouraged’ to adopt

policies that bring the ratio down to the target within a reasonable period. We discuss the

mechanics of such adjustments further below, but meanwhile it is worth asking the more

general question, namely how exactly do countries with high ratios get them down. In other

words, what does historical experience reveal about such processes?

This is an important question, as recent discussions about debt reduction seem to imply that

countries should normally get their debt levels down by ‘simply’ paying off the outstanding

debt over a period. On the whole, though, this has not been the universal practice. Instead,

countries have often opted for either formal default or a spell of inflation, and in either case

this is sometimes aided by moderate economic growth rates. Which is best, or which is

feasible in a given case depends both on the local monetary policy environment and on the

currency in which the bulk of the debt is denominated. Thus in the postwar period, the UK,

most of whose debt was denominated in the home currency, the pound sterling, brought down

its public debt-to-GDP ratio quite dramatically through a mixture of economic growth (since

raising GDP raises the denominator in the debt-to-GDP ratio) and modest inflation, without a

formal default. The process was certainly helped by a degree of fiscal discipline, the

government mostly keeping government deficits and surpluses within a narrow range of plus

or minus two percent of GDP. For most of the period, however, there was no attempt – or

need – to deliver very large primary surpluses of the sort currently discussed for highly

indebted countries. In contrast, most of Argentina’s debt was denominated in US dollars, so

when the debt became unmanageable a few years ago, the country had no choice but to

default and also to devalue the currency.

What do these observations imply for SKN? It seems to us that they imply four things, some

of which are elaborated further later on:

(a) Dealing with debt through a spell of inflation is probably not a serious or realistic option,

in part because of ECCB commitments to price stability and the fixed exchange rate

24

between the EC$ and the US$, in part because in a fixed exchange rate regime, domestic

inflation quickly erodes domestic competitiveness. Also, at least in theory, inflation only

works in this way to bring down the real burden of debt when it is ‘unexpected’, as

expected inflation ought to be incorporated into the average interest rates payable on

government debt.

(b) However, if US policies to stimulate their economy, including the fiscal expansion

package of 2009-10, quantitative easing (QE) by the Federal Reserve, and the recently

announced second round of QE (known as QE2), end up stimulating inflation of the US

economy two or three years down the line, as must be moderately likely, then it would

make good sense for the countries of the ECCU to allow their respective domestic

inflation rates to track US inflation; this will maintain competitiveness while eroding the

real value of each country’s indebtedness, including that of SKN.

(c) Economic growth provides a second channel through which public debt-to-GDP ratios

can be brought down. This is potentially a very important route, and in the next subsection we discuss ways of stimulating growth in SKN.

(d) The last way of bringing down debt levels is through fiscal discipline, sustained over

quite long periods. This is the most difficult route, but also the most effective in terms of

fostering conditions for favourable long-term development. What it typically means is

cutting back on government spending while taking steps to stabilize or even raise

revenues, hence generating a substantial primary surplus. A recent paper that studied a

number of successful debt reduction episodes in Europe found that a ‘drastic and

permanent fiscal consolidation mainly concentrating on the expenditure side’ was usually

the key to success (Nickell et al., 2010). We explore the implications of this line of

argument for SKN below.

From this discussion, it is clear that for a highly indebted country such as SKN, it is vital for

any serious analysis of the macroeconomic framework to include an examination of the debt

burden and its sustainability, leading on to ways in which the total debt can be brought back

down to more manageable levels. None of this is straightforward, and analysing the debt

cannot be done in a completely objective manner since any future projections are inevitably

subject to a high degree of uncertainty. Nevertheless, it is extremely helpful to develop

projections relating to a number of possible scenarios, as is already done by GoSKN, in order

to contribute to the development of appropriate policies.

In this regard, the IMF has developed a very useful framework for analysing the question of

debt sustainability at country level; see IMF (2008a) and Escolano (2010), among other

sources10. However, while technically correct, the IMF’s DSA framework is quite complex to

apply, very demanding in terms of its data requirements, and hence not especially intuitive in

its approach. For this reason, we have chosen in this report to develop a more ‘rough and

ready’ approach that we think is easier to understand and use, and hence more practical as a

tool to guide policy-makers. Our approach is outlined relatively formally in Annex 1, while

here we offer a more informal account.

What we propose is built around a simple, single period model of the economy in which there

is an initial level of outstanding debt, and available data on the debt servicing obligations in

the current period, this referring both to interest payments and repayments of principal. It is

then a decision for the government, how much new debt to take on during the period. With

10

The World Bank has also developed an approach to debt performance management using 15 indicators, and

based on the well established PEFA methodology. For our purposes, we find this less useful than the IMF’s

approach, but for details, see World Bank (2009).

25

data on tax rates and revenue raising; government spending of all types, and the projected

growth rate of GDP, we can then step through the model for one period and project what debt

will be outstanding at the start of the next period.

What we find, by computing paths of total debt and the debt-to-GDP ratio for a variety of

initial conditions and fiscal parameters, is that starting from the country’s current public debtto-GDP ratio (already above 1.8, as noted), it proves very difficult to devise a fiscal policy

mix that is capable of bringing the ratio down (see Table A1 in Annex 1). Rapid economic

growth certainly helps considerably, as does a high average tax rate combined with low

government spending (implying a large primary surplus). But under present conditions it will

not be easy to achieve the needed growth rates (though we examine this more carefully

below), and we have serious concerns over the political economy of the necessary fiscal

policy mix. In other words, will the citizens of SKN be prepared to tolerate the fiscal policy

mix that would be required to bring down the debt-to-GDP ratio? Or will the politicians be

prepared to implement such a mix? Moreover, with the debt-to-GDP ratio standing at such a

high level, the government’s ability to bring it down – leaving aside the tricky political

economy consideration just mentioned – will be vulnerable to further adverse economic

shocks.

Once the public debt-to-GDP ratio has been brought down, the ‘space’ for domestic fiscal

policy to operate widens considerably. Even with a debt-to-GDP ratio of 1 (i.e. 100%), still

fairly high by European standards11, though below the ratios of the two problem countries,

Greece and Ireland, our scenario analysis in Annex 1 shows that there is already a fairly wide

range of fiscal policy combinations that can sustain or even reduce the ratio. This debt ratio,

therefore, is thus far more manageable for the government and less vulnerable to troublesome

adverse shocks. This is, naturally, even more true for the lowest debt-to-GDP ratio we

consider, of 0.6 (i.e. 60%), which would then be in line with the norm advised by the ECCB.

This analysis implies, we believe, shows just how fragile the current financial situation facing

the Government of St Kitts and Nevis appears to be. Current debt levels are only sustainable

with quite draconian fiscal policies, requiring both a high tax take and very tough controls on

government spending. Moreover, such policies will only succeed if the wider economic

environment remains moderately benign, with no substantial adverse shocks. Accordingly,

some debt restructuring might be needed, in agreement with the country’s principal creditors,