Innovation management within the plural form network

advertisement

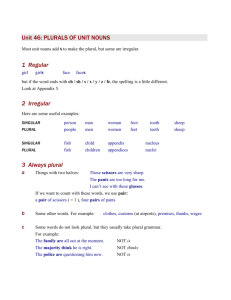

Paper to be presented at the EMNet-Conference on "Economics and Management of Franchising Networks" Vienna, Austria, June 26 – 28, 2003 Innovation management within the plural form network Gérard CLIQUET IGR-IAE, 11 rue Jean Macé CS 70803 RENNES Cedex 7 FRANCE Tel : +33 02 23 23 78 51 Fax : +33 02 23 23 78 00 Email: gerard.cliquet@univ-rennes1.fr And NGUYEN Minh-Ngoc IREIMAR - Campus de Beaulieu, Bât 1, 263, av. du Général Leclerc 35042 Rennes, FRANCE Tel : +33 2 23 23 51 49 Fax : +33 2 23 23 63 05 Email: nguyenminhngoc@netcourrier.com CREREG, UMR CNRS 6585 University of Rennes 1 (France) Abstract: Nowadays, most retail chains are organized in a network structure, which operates under the principals of mutual communication and cooperation for lower overhead cost, increased responsiveness and flexibility, and greater operational efficiency (Lozenzoni and Baden, 1995). In addition, thanks to interfaces between many units, the network is a powerful tool to foster innovation. However, networks can also block innovation because of the divergence of interests among units (Hagedoorn, 1995). A franchised network is an illustration of this, due to the fact that franchisees, as independent entrepreneurs, have the right not to adopt all the modifications proposed by the franchiser. A solution is to use the plural form, associating franchise and company arrangements. In reality, the plural form is increasingly used in retailing; it has advantages over the pure franchised and wholly owned chains in terms of innovation. This paper deals with innovation management within the plural form network. Firstly, we point out difficulties in managing innovation that network operators have to cope with. Secondly, we explain why the plural form could facilitate innovation. And finally, we study the innovation process and build the process models for how innovation is made and managed in the plural form network. Data for analysis are obtained by interviews with network operators in France. On the whole, this work tends to show the superiority of the plural form and has a practical purpose that is to help the plural form network to optimize the management of innovation projects. Key words : Franchising, plural form network, retail and service sectors, innovation process, innovation management 1 Introduction Innovation is increasingly seen as a powerful way of securing competitive advantage and one of the key factors in a firm’s strategy for survival (Drucker, 1985). Innovation is not easy to manage due to its characteristics of complexity, change and uncertainty. For a network organization that possesses geographically dispersed business units, the management of innovation is more complex and thus requires more effort. The purpose of this paper is to investigate how innovation is made and managed within business networks, especially focusing on the retail and service sectors. Retail and service networks may operate as unique forms chains (i.e. franchised pure and wholly owned chains) or plural form networks associating frequently franchise and company arrangements. Overall, this paper deals with innovation management within the plural form network. It is hypothesized that the plural form could be a better organizational option for point-of-sale network in terms of developing innovation. Firstly, after a brief summary of the literature on advantages and disadvantages of network structure, we point out difficulties faced by retail network operators in the innovation management. Secondly, we explain why the plural form having both franchise and company arrangements could facilitate innovation. Our analysis is based on interviews with French franchisers in various sectors of activity and on the results of past research (Bradach, 1998; Lewin-Solomons, 1998). We finally propose the models of innovation process, which are expected to help the plural form network operators to optimize the management of their innovation projects. I, Innovation and network organization A. Advantages of the network structure The term “network”, by its definition, refers to a set of business units and relationships which connect them (Fombrun, 1982). Networks operate under the principals of mutual communication and cooperation for lower overhead cost, increased responsiveness 2 and flexibility, and greater operational efficiency (Lozenzoni and Baden, 1995). They allow companies to gain access to complementary resources and competence, which are not available internally. Networks are dynamic and flexible structures subject to change (Hagedoorn, 1995). Innovation could be more fostered thanks to interfaces between two or more parties. In other words, innovation could be seen as an efficient process stemming from a network of several actors. Various network’s attributes which influence the innovation capability can be considered such as flexibility, speed and network learning system. The network structure provides chains with the flexibility to respond to continuous evolution and revolution in products, technologies and markets. Empirical investigations have shown that alliances of small firms can archive higher flexibility and efficiency than a single-plant enterprise (Semlinger, 1993). A greater organizational flexibility permits greater abilities to adapt to the changing market conditions (Cliquet, 2000), and so a better accommodation of novelty, innovation and local responsiveness. Speed is viewed as an advantage of networks; speed is also essential for a successful innovation. With the co-operation’s mechanism in the strategic development, networks have generally an ability to respond to customer’s needs faster than a single unit does. Hence, networks promote a means to reduce the time of the innovation process. Moreover, speed offers three majors payoffs (Cooper, 1993.) - Speed yields competitive advantage. The ability to respond to customers’ needs and changing markets faster than competitors and to beat competitors to market with a new product is often the key to success. - Speed yields higher profitability. The revenue from the sale of the product is realized earlier, and the revenues over the life of the product are higher, given a fixed window of opportunity and hence limited product life. 3 - Speed means fewer surprises. The short timeframe reduces the odds that market conditions will change dramatically as development proceeds. Speed appears to be really a competitive weapon of the network structure. Co-operation offers companies the availability of a wide range of resources almost immediately. Under the current competitive circumstances, the two basic resources are knowledge and relationships. Pooling those resources is necessary for a business network to get stronger. The network organization form increases learning (Hakanson et al, 1999), by providing linkages with external learning partners in long-term relationships that facilitate information sharing. The diversity of information that resides in a network is greater than that in a single firm. In fact, the network as a learning system provides skills to organizations by creating, acquiring and transferring knowledge and modifying their behavior in order to figure out new perspectives (Garvin, 1993). Networks are powerful tools to foster innovation in company and industry-wide (Gomez Arias, 1995). As for the retail and service sectors, it is observed that this type of organization is more generally used and also enhances many activities including innovation. In this paper, we concentrate on retail and service sectors. There are various network structures that are popular in retailing. Bradach (1998) has proposed three types of network: a centralized company-owned system, a decentralized franchise system and a plural form network that associates both franchise and company arrangements. The first kind of system is the basic hierarchical network where there is a center (operator) with dependent units. Managers of these units are employees of the chain operator and they work under the instructions of that operator. On the contrary, the franchising system is a decentralized business network, which incorporates elements of both market and hierarchy (Williamson, 1991) and was called by Shane (1996) the hybrid organization. Indeed, the franchiser retains the ownership and authority over the use of a trade name, the know-how in contracting with 4 independent franchisees. The operator-franchisees relationship is a partnership between owners. Thirdly, the plural form network associates the strictly hierarchical mechanism of the company arrangement and the hybrid market/ hierarchy of business format franchising. Today, many retail chains adopt this organizational structure because the plural form provides a significant number of advantages in terms of marketing (Cliquet, 2002), of management (Bradach, 1997, 1998), of network performance (Sorenson & Sørensen, 2001) and survival ability (Cliquet, Perrigot, 2002). B. Some problems related to innovation faced by retail networks However, networks have some major drawbacks. The more units with different objectives and strategic agendas are involved, the more time consuming is the process of decision making. Therefore, close attention must be given to the trade-off between faster implementation and slower decision making. Required relationships and norms entail drawbacks and hazards such as increasing complexity, less autonomy, information asymmetry (Hagedoorn, 1995). If network structure can promote innovation, it can also block it. It will be more complicated for the network to manage innovation. In reality, the operators of retail networks frequently have to confront this problem. We will explain it hereafter. The network management is different from the management of a single unit in the fact that the network operator has to control the set of geographically dispersed units. Many difficulties result from this characteristic of the network organization. First, the operator hardly knows the events, which happen at local units; so, may lose some control, especially over remote units. When an innovation occurs, the problematic is how to implement the innovation in maintaining the uniformity of the network. Bradach (1998) defined uniformity as a key element of the business format chain. The objective of every chain is to build the good image of its concept and keep it identical across all units (Lafontaine & Shaw, 1999). 5 The evolution of the concept is essential for the network to survive in competitive circumstances, but it also makes the maintenance of uniformity a major challenge for network operator. It is difficult for the franchiser to have his concept deeply evolved in a pure franchised chain when this evolution requires an important investment of franchisees. The franchiser can not impose everything on his franchisees but rather persuade them to follow innovation. In reality, implementing an innovation at company-owned units does not cause problem. However, that requires efforts to diffuse innovation to franchised units. One of the drawbacks of franchising is the fact that franchisees have the right not to adopt all the modifications required by the franchiser in their own stores. The franchiser sometimes has to persuade his franchisees and stays very flexible. In reality, there are many solutions: Catena (French do-ityourself network) provided financial help for its franchisees to set up a new commercial brand with a new logo; Sweetlit (French home furnishing network) gave its franchisees a certain period to completely implement an innovation. In the worst case, as in the case of Galler Chocolat (Belgium confectionery network), if franchisees do not want to implement a new concept, they can stay as they are and continue to work as they used to do. So, in chains that have a rigid concept and where uniformity is highly required, it is necessary to maintain a right proportion of franchised and company-owned units, which can influence the chain performance (Sorenson & Sørensen, 2001). The same thing happens with the systemwide adaptation. When an innovation is proposed, the network operator has to adapt it in all different contexts, particularly while there are points of sale abroad. The adaptation of a given innovation must be different from one country to another, from one region to another or even from one unit to another. We agree with Bradach (1998) in stating that systemwide adaptation is the most complex and difficult of all management challenges facing retail networks. 6 We state that, in retailing, the plural form organizations, composed of franchised and company-owned units, can more or less deal successfully with the obstacles mentioned above. The next section will show how the plural form could facilitate innovation. Our qualitative analysis is based on results of past research in the fast-food industry by Bradach (1997) and Lewin-Solomons (1998) completed by our interviews with number of French franchisers in various sectors of activity. II, Influence of the plural form on innovation The plural form seems to enhance the network's ability to innovate, explicitly in three following aspects of the innovation process: innovation generation, innovation programming and innovation implementation. Idea generation Generating ideas is the first stage of any innovation process. The plural form seems to produce a greater variety of ideas than either arrangement could do by itself. By mixing a company arrangement with expert staff and a franchise arrangement with its businessexperienced franchisees, the plural form benefits from two possible sources of information. Ideas for new products or services can be developed in two ways: by the franchiser and his company staff and by individual franchisees. Within a plural form network, the franchise arrangement positively affects the systemwide development. With their experience in local markets, the franchisees play an important role in the ideas generation stage. They are regularly in contact with consumers. They can give local information feedback, if they want to, in order to help the chain’s operator to make decisions. “Yes, franchisees are a significant source of innovation because, thanks to them, we have the feedback on consumer behavior. This enables us to adjust our concept of product or service according to the consumer’s demand”. (French franchiser Sweetlit, home furnishing) 7 “If franchisees come up with an idea, it should be taken. Franchiser and franchisees always work in groups. There are not two separated entities”. (French franchiser Sweetlit) “We appreciate franchisees ideas because these ideas came from the local market. We have some franchisees of high level who can reason, seek for and bring innovation ideas. It is one of the great forces of franchising”. (French franchiser Feu Vert, car accessories) Bradach’s study has shown that local managers in the company arrangement, as a franchiser’s employee, rarely came up with innovative ideas. By contrast, everyone agreed that franchisees were an important source of ideas, regarding the quantity of information and the quality as well. Explanations for this can be found while analyzing two fundamental differences between a company unit and a franchisee: incentives and initiatives (LewinSolomons, 1998). Franchisees have strong incentives to manage their own business as well as possible because they are independent entrepreneurs who keep profits produced by them, once the royalty payment is made. They are responsible for the results of their units, so take part in the network management and innovation activities. On the contrary, the company manager’s incentives are lower-powered because they operate as employees within a standard corporate hierarchy. As far as initiatives are concerned, franchisees are much more independent than company managers are. They exercise a great deal of initiatives to make their business successful. Whereas company managers have to obey to authority, do not like taking risk and depend on the chain operator’s decisions, franchisees have freedom in acting on their own. These kinds of incentives and initiatives demonstrate that a franchised outlet tends to perform better than company unit in generating innovations. For their own profits, franchisees regularly think about making the network more efficient. Ideas from franchisees once shared and accepted by other units will be converted into true and profitable projects. Sometimes, owing to the presence of franchisees, company managers become more dynamic 8 and motivated. Through a mutual learning process, company units will be aware of their responsibility to daily develop the network (Bradach, 1997). Bradach (1998) cites franchisers’ arguments as illustrations. “If franchisees see a competitor doing something, they will quickly call us and want to do it themselves.” (Franchiser Hardee, fast food). According to the Kentucky Fried Chicken CEO, franchisees accelerated the process of identifying opportunities for innovation: “Ultimately we would identify these issues, but franchisees sometimes enable us to see things earlier. “Franchisees are good at focusing on things that really hit the bottom line”. From our own study on French franchisers, we can also notice: “Sometimes, franchisees come up with ideas that we have never thought of before” (Franchiser Feu Vert, car accessories). In short, within the plural form structure, franchisees will develop their capabilities to influence network performance in terms of innovation. For instance, franchisee’s local responses push company units to be more dynamic, encourage the chain operator to develop more new products/services or evolve the existing concept. Franchisers often rely on the information, which comes up from local markets to define their policies. This flow of information is rich qualitatively speaking because its stems from the direct contacts of local units with consumers. Testing and evaluating ideas After having innovative ideas, it is important for the operator to evaluate whether the innovation projects work as expected. Franchisees rarely participate in the formal testing and evaluating process, mainly because the characteristics of a franchise contract have nothing to do with field-testing. They are not ready to bear the risk of testing new ideas in their units. Therefore, it is easier to work with company units. In every network we studied, innovation ideas are conceived by the franchiser before being realized and diffused in the whole 9 network. Franchisees rarely participate in this stage because the project’s programming is part of the network operator’s mission and tests for a new concept will be firstly carried at company-owned outlets. Still, franchisees do play a certain role in testing and evaluating innovation ideas. The independent thinking of franchisees is very valuable for the franchiser to check and balance before making decisions. In other words, the franchiser listens to his franchisees and acts according to their feedback. Franchisees tend to say exactly what they think, either good or bad things. These obvious and frank opinions are helpful to the franchiser to adjust the new concept and make good decisions. “We have franchisee committees for many aspects like advertisement, information… We cannot do anything without their opinion” (according to the director of Catena’s expansion department). Implementation stage In a plural form network, each arrangement has an effect on the way the other arrangement works. A reciprocal influence positively affects the behavior of local units toward innovation. The chain operator can persuade franchisees to adopt an innovation by firstly implementing it in company units. The company’s adaptation will directly affect the decision making process of franchisees. The network operator can also use the company’s data to demonstrate the viability of the proposed innovations. When new ideas are successfully adapted to company units, why not implement them in franchised stores? So, the convergence of interest created by the plural form can encourage the franchisee’s acceptance. In his turn, the franchisee also provides feedback. The chain operator can use the franchisee performance to put pressure on company units or to set performance benchmarks for them. In short, the relative weakness of a pure company arrangement is a function of few locally generated innovations, low-powered incentives to innovate, the absence of initiatives and experience, and the low level of local pressure on the franchiser to develop innovation. A franchise arrangement provides these four things lacking in a company arrangement. First, 10 franchisees are an important source of local ideas. Second, franchisees have strong incentives to generate new ideas for the network’s competitive advantage. Third, franchisees are someone who has a good intuition based on their experience. Finally, franchisees serve as a strong constituency pushing forward company managers and the chain operator to be more dynamic and to generate more ideas. Generally, the innovation programming (comprising innovation test and evaluation) is not composed of formal tasks for franchisees but it is at the franchiser’s charge. However, the franchisee feedback is valuable for the network operator to check and adjust an innovation project. The speed of implementing an innovation is very high in pure company chains, but low in pure franchise arrangements, and considered as medium in plural form networks. Actually, the plural form enables to accelerate the decision and implementation processes in franchised units, mainly because of the use of company units as screens for persuading franchisees to adopt innovations. In sum, the plural form seems to be a better option in terms of supporting innovation, in comparison with the pure franchised and wholly owned chains. III, Innovation process modeling A. A literature review on innovation process research There are two streams of research on the innovation process (Wolfe, 1994). The first, called stage model research (Ettlie, 1980; Perl, 1983), conceptualizes innovation as a series of stages that unfold over time. The purpose of stage model research is to determine whether innovation process involves identifiable stages and, if so, try to nominate and place these stages in the right order. The second approach involves in-depth and longitudinal research conducted to fully describe the sequences of innovation process and the conditions that determine the innovation process. In this paper, we deal with the first approach. 11 An impressive number of innovation process models have been described in the literature. A typology has been proposed according to various types of innovation (Saren, 1984): Departmental-stage models consider the innovation process in relation with operational department of the innovative firm (R&D, Design, Technique, Production, Marketing). Decision-stage models are related to the series of decisions made (collecting information, evaluating information, taking decision, identifying uncertainty) Conversion process models deal with the innovation development like a process of transformation of raw materials and information (input) into end product (output) Response models are built as a function of the firm’s responses to both internal and external stimuli (market demands, new product ideas, conception, acceptation or rejection of innovation…) Activity-stage models define an innovation process as the succession of stages or activities As we have mentioned above, stage model research places a premium on the temporal sequence of activities in the development and implementation of innovation. The models by activity are mostly considered. Table 1 presents different models proposed in the literature As you can see in Table 1, many activity-stage models of innovation process are proposed and there is significant overlap among the models. Therefore, it is possible to synthesize an innovation process in the following general pattern: a generation of idea, a decision-making unit becomes aware of an innovation idea, an evaluation considering a problem or opportunity matched to the innovation, a test through which the innovation costs and profits are appraised, a decision to adopt or reject innovation, an implementation of innovation, a review of the innovation decision and a confirmation, a diffusion of innovation. 12 The management of innovation within networks has its specific points. It is interesting to focus on the process for how innovation is made and managed within network structure. Until now, no innovation process model for retail networks exists. The next section tends to describe our attempt towards building such a model. 13 Table 1: Activity-stage models of innovation process1 Author Zalman, Duncan & Holbek (1973) 1 Daft (1978) Idea conception 2 Knowledge/ awareness 3 Attitude formation Ettlie (1980) Awareness Evaluation Tornatsky et al. (1983) Awareness Matching /selection Rogers (1983) Knowledge Meyer & Goes (1988) Knowledge/ awareness Cooper & Zmud (1990) Initiation (push or pull) 6 Decision Proposal Adoption/ Implementation rejection Trial Selection Bradach (1998) Idea generation Evaluation Composite Ideas generation Evaluation 8 Adoption /rejection Implementation Decision Implementation Adoption Implementation Adoption Adapt/develop/ install Acceptance/ usage Development Test/ confirmation Test Decision Test 7 Initial implementation 9 10 Sustained implementation Adoption/ Implementation rejection Evaluation / choice Idea generation 1 5 Persuasion Jallat (1994, 1999) Awareness 4 Persuasion Routinization/ commitment Confirmation Expansion Incorporation/ routinization Infusion Diffusion Implementation Adoption Implementation Confirmation decision Routinization Diffusion Adapted from Wolfe (1994) 15 B. Innovation process model for the plural form network Innovation in retailing: About the context of this study Innovation in retailing refers to two fundamentally different activities: radical innovation of the business system or sudden innovation and gradual improvements or regular innovation within the current structure (Liebmann, 2003). Radical innovation in retailing means the current structure undergoes fundamental change. To a certain extent, the firm will be transformed in the future, e.g., new commercial system like supermarket, e-business, etc. We focus more on the second type of retail innovations: gradual and continuous innovations. In this case, innovations mean improvements to existing operations in day-today business, i.e. new store concepts or services, new presentation and function of existing products, new distribution channel, new marketing systems (Barreyre, 1980), cost reduction programs, more efficient logistics processes (Leibmann, 2003). It is noted that this type of innovation is often made in retail networks. So, we decided to choose this type of innovation as the application field of our conceptual models. Proposition of innovation process models Studying the issue of innovation within a plural form network, we find that it is possible to build an innovation process more efficiently applied to the plural form organizations. During our interviews with franchisers, we found out the need for communications between franchiser, franchisees and company units for more successful innovation. Rogers (1983) defined communication as the process by which participants create and share information with one another in order to reach a mutual understanding. The pivotal role of effective communication has been substantiated in many innovation studies. In fact, many scholars in the field of innovation management have argued that innovation processes are 16 essentially communication and information processing activities (Allen, 1985; Brown and Utterback, 1985; Ebadi and Utterback, 1984; Fidler and Johnson, 1984; Souder and Moenaert, 1992; Tushman, 1979; Tushman and Nadler, 1980). In a plural form network, because of the problem of divergent interests, the communication stage is needed to make an innovation project more profitable for every unit. Indeed, in the communication stage, franchiser, franchisees and company managers will meet each other and discuss the feasibility of innovation ideas. When the new ideas are accepted by a majority of people, the chance to succeed in following stages and in the whole innovation project will be higher. So, we propose to add a communication stage in the innovation process. Consequently, our model comprises five stages: ideas generation, communication, innovation project design, test and evaluation, and innovation diffusion. In principle, our model is based on the innovation process models proposed in the literature. It essentially differs from others in the stage of communication. The position of this stage may be changed according to where the innovation ideas come from. We distinguish two cases: Model 1 is considered when innovation comes from the franchiser. Model 2 is applied if innovation is initiated by the franchisee. The models are composed of three parts: stage, innovation process and place. There are 5 stages in each model: ideas generation, communication, innovation project design, test and evaluation, and innovation diffusion. In the column of innovation process, we describe by chronological sequence, actions that should be taken at the place as you can find in the third column of the model. In Model 1, communication is stage number 4. In fact, thanks to the local unit feedback, the competitive intelligence and the market analyses, the franchiser can have some innovative ideas. The innovation project will be then programmed by the franchiser, 17 technically and commercially. Next, the prototype will be tested at company units. If the test gives favorable results, switch to the communication stage. If not, return to the previous stage to review and make adjustments. The communication is made through committee meetings and at franchised units with the purpose of informing and persuading franchisees to adopt, to train and give technical and financial aids for the implementation. Finally, it is the innovation diffusion where new product and services will be commercialized in all units Model 2 differs from model 1 by the fact that communication is the second stage. Because when the innovation idea comes from a franchisee, it must be transferred to other units for review before it comes to the elaboration step. The two models are particularly designed for the plural form networks, which seem to be in the majority of retail and service networks in France. These preliminary models are based on our observations and on what the interviewees told us. We shall, in the near future, test and improve these models among several chain operators in France. 18 INNOVATION PROCESS IN RETAIL PLURAL FORM NETWORKS Model 1: If innovation comes from the franchiser Stage Ideas generation Innovation process Local unités feedback Competitive intelligence Place Market analyses Franchiser or network operator Innovation ideas Elaboration of innovation project Technical preparation Programming Commercial preparation (marketing) Franchiser’s R&D department Prototype Test and evaluation Unfavorable results Test and Adjustment (If necessary) Company units Favorable results Communicat ion Diffusion To inform franchisees To persuade (if necessary) Training Technical & financial aids System-wide commercialization Committee reunions and franchised units Franchisees Company units 19 INNOVATION PROCESS IN PLURAL FORM NETWORKS Model 2: If innovation comes from the franchisee(s) Stages Innovation process Ideas generation Contacts with clients Place Competitive concepts in local markets Franchisees Innovation ideas Propose these ideas Committee Reunions with Franchiser and other units Communicat ion Reject No Discussion: Is the project profitable for all units? Yes Elaboration of the innovation project Technical preparation Programming Commercial preparation Prototype Test and evaluation Franchiser Unfavorable results Test and adjustment ( if necessary) Company units Favorable results Diffusion Training Technical & financial aids All units System-wide commercialization 20 Conclusion This paper offers a qualitative analysis of the influence of the plural form on innovation management. It couples different research on the plural form choice (Bradach & Eccles, 1989; Bradach, 1997, 1998; Lewin-Solomons, 1998, Cliquet et al., 1998, Sorenson & Sorensen, 2000; etc.) These authors have shown the superiority of the plural form over the unique form chains in terms of management, of marketing and network performance. We approached in this paper another advantage of the plural form regarding the innovation ability. Actually, the idea that the plural form seems to facilitate innovation was initiated by Bradach in 1998 and later raised by Lewin-Solomons in her studies on U.S. fast-food chains. We have strengthened this idea by examining it in others sectors and analyzing it in the different stages of the innovation process. Two models of innovation process have been proposed for plural form networks. Effectively, they require more empirical examination in a larger sample. That constitutes one of our future works. References Allen T.J. (1985), Managing the Flow of Technology: Technology Transfer and the Dissemination of Technological Information within the R&D Organization, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Barreyre P.Y. (1980), Typologie des innovations, Revue française de Gestion, jan-feb 1980, 9-15 Bradach J.L., Eccles R.G. (1989), Price, Authority, and Trust: From Ideal Types to Plural Forms, Annual Review of sociology, Vol. 15, 97-118 Bradach J.L. (1997), Using Plural Form in the Management of Restaurant Chains, Administrative Science Quarterly, vol. 42, issue 2,276-303 Bradach J.L., (1998), Franchise organization, Harvard Business School Press Brown J.W., Utterback J.M. (1985), Uncertainty and technical communication patterns, Management Science, Vol. 31 No. 3, 301-11. Cliquet et al. (1998), Plural Form Networks: Franchise vs. Company Arrangements: Conflicting or Complementary Organizations? Report on research contract commissioned by the French Franchise Federation (FFF) Cliquet G. (2000), Plural Forms in Store Networks: a Model for Store Network Evolution, The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 10, 4, 369-387 Cliquet G. (2002), Les réseaux mixtes franchise/succursalisme : Apport de la littérature et implications pour le marketing des réseaux de points de vente, Recherche et Applications en Marketing, 17, 1, 57-73 Cliquet G., Perrigot R. (2002), An Application if Survival Analysis to French Hotel Networks, paper presented et the 16th Annual International Society of Franchising Conference, Orlando, Florida, February 8-10, 2002 Cooper RB., Zmud RW. (1990), Information Technology Implementation Research: A technological Diffusion Approach, Management Science, 36, 123-39 Cooper R.G. (1993), Winning at New Products. Accelerating the Process from Idea to Launch, AddisonWesley, Reading, MA Draf RL. (1978), A Dual core Model of Organizational Innovation, Academy of Management Journal, 21, 193210 21 Drucker P. (1985), Innovation and Entrepreneurship, New York: Harper & Row Ebadi Y.M., Utterback, J.M. (1984), The effects of communication on technological innovation, Management Science, Vol. 30 No. 5, May, 572-85. Ettlie JE. (1980), Adequacy of stage models for decisions on adopting of innovation, Psychological Reports, 46, 991-105 Fidler L.A., Johnson J.D. (1984), Communication and innovation implementation, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 9 No. 4, 704-11 Fombrun C.J. (1982), Strategies for Network Research in Organizations, Academy Management Review, 7, 2, 280-91 Garvin D.A. (1993), Building a Learning Organization, Harvard Business Review, July-August 1993, 78- 91 Gomez Arias J.T. (1995), Do Networks Really Foster Innovation? Management Decision, Vol.33, No 9, 52-56 Hagedoorn J. (1995), A Note on International Market Leaders and Networks of Strategic Technology Partnering, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 16, 241-50 Hakanson H., Havila V., Pedersen AC. (1999), Learning in Network, Industrial Marketing Management 28, 443–452 Jallat F. (1994), Innovation dans les services : les facteurs de succès, Décisions Marketing, N0 2, 23-30 Jallat F. (1999), Spécificités des processus et gestion de l’innovation dans les services, Market Management, No 4, 31-42 Lafontaine F., Shaw K.L. (1999), Targeting Managerial Control: Evidence from Franchising, Working paper University of Michigan Business School Lewin-Solomons S.B. (1999), Innovation and Authority in Franchise System: An Empirical Exploration of the Plural Form, Journal paper no. J-18005 of the Iowa Agriculture and Home Economics Experiment Station, Project No. 3530 Lewin-Solomons S.B. (1998), The Plural Form in Franchising : A Synergism of Market and Hierarchy, Working paper, University of Cambridge and Iowa State University Liebmann HP., Foscht T., Angerer T. , Innovation in Retailing : Gradual or Radical Innovations of Business Models, European Retail Digest, Issue 37, 55-60 Lozenzoni G., Baden fuller C. (1995), Creating a Strategic Center to Manage a Web of Partners, California Management Review, 37, 3, 146-63 Meyer AD., Goes JB. (1988), Organizational Assimilation of Innovations: A Multilevel Contextual Analysis, Academy of Management Journal, 31, 897-923 Pelz D.C. (1983), Qualitative case histories of urban innovations: Are there innovating stage? IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 30, 60-7 Rogers E.M, (1983), Diffusion of Innovation, New York, The Free Press Semlinger K. (1993), Small Firms and Outsourcing as Flexibility Reservoirs of Large Firms, in Graher G., The Embedded Firm: On the Socioeconomics of Industrial Networks, London NewYork, Routledge, 1993 Saren M.A. (1984), A Classification and Review of Models of the Intra-firm Innovation Process », R&D Management, vol.14, no 1, 11-24 Shane SA. (1996), Hybrid Organizational Arrangements and theirs Implications for Firm Growth and Survival: A Study of New Franchisers, Academy of Management Journal, 39, 1, 216-234 Sorenson O., SØrensen J.B. (2001), Finding the Right Mix: Organizational Learning, Plural forms and Franchise Performance, Strategic Management Journal, 22, 713-724 Souder, W.E. and Moenaert, R.K. (1992), "Integrating marketing and R&D project personnel within innovation projects: an information uncertainty model", Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 29 No. 4, July, pp. 485512. Tushman, M.L. (1979), "Managing communication networks in R&D laboratories", Sloan Management Review, winter, pp. 37-49. Tushman, M.L. and Nadler, D.A. (1980), "Communication and technical roles in R&D laboratories: an information processing approach", Management Sciences, Vol. 15, pp. 91-112. Williamson OE. (1991), Comparative Economic Organization: The Analysis of Discrete Structural Alternatives, Administrative Science Quarterly, 36, 269-296 Wolfe R.A. (1994), Organizational Innovation: Review, Critique and Suggested Research Directions, Journal of Management Studies, 31; 3, 405-431 Zalman G., Duncan R., Holbek J. (1973), Innovations and Organizations, New York: Wiley 22